Conduction in Liquids Note

CONDUCTION IN LIQUIDS NOTE : The resistances of the above depend to a great extent on the Note: The resistances of the above depend to a great extent on the state of the surfaces, moisture, grease, etc., reducing the resistances enormously. The resistances are also greatly reduced for small increases in temperature. In actual practice, unless great care has been taken in keeping the surfaces clean, the effectual resistances of the substances may be or f a of the value shown in the table.

there should be a certain lag in its response to the stimulus if this view is correct.

Dielectric Conductors.—A large volume of unsystematic work for technical purposes has been carried out with what may be termed dielectric conductors or insulators. For most purposes the property required is the absence of conductivity, and there fore attention is centred mostly upon those substances which have the greatest possible resistance and can be made use of for In fused salts and conducting solutions the passage of an electric current is always accompanied by definite chemical changes; the substance of the conductor or electrolyte is decomposed, and the products of the decomposition appear at the electrodes. The chem ical phenomena are considered in the article ELECTROLYSIS ; we are here concerned solely with the mechanism of this electrolytic conduction of the current. In metallic conduction it is found that the current is proportional to the applied electromotive force— a relation known by the name of Ohm's law. According to this law I=E/R, where I is the current, E the electromotive force and R the resistance of the circuit. Ohm's law has been confirmed in the case of metallic conduction to a very high degree of ac curacy and Kohlrausch was the first to show that an electrolyte possesses a definite resistance which has a constant value when measured with different currents and by different methods.

Measurement of the Resistance of Electrolytes.—There are two effects of the passage of an electric current which prevent the possibility of measuring electrolytic resistance by the ordinary methods with the direct currents which are used in the case of metals. The products of the chemical decomposition of the elec trolyte appear at the electrodes and set up the opposing electro motive force of polarization, and unequal dilution of the solution may occur in the neighbourhood of the two electrodes. The polarization at the surface of the electrodes will set up an op posing electromotive force, and the unequal dilution of the solu tion will turn the electrolyte into a concentration cell and produce a subsidiary electromotive force either in the same direction as that applied or in the reverse according as the anode or the cathode solution becomes the more dilute. Both effects thus involve in ternal electromotive forces, and prevent the application of Ohm's law to the electrolytic cell as a whole. It is therefore necessary to eliminate both these effects before attempting to measure the resistance.

The usual and most satisfactory method of measuring the resistance of electrolytes is that of Kohlrausch and Holborn, which consists in eliminating the effects of polarization by the use of alternating currents, i.e., currents that are reversed in direction many times a second. The chemical action produced by the first current is thus reversed by the second current in the opposite direction, and the polarization caused by the first current on the surface of the electrodes is destroyed before it rises to an ap preciable value. The polarization is also diminished by increasing the area of the electrodes, which can be brought about to a very high degree by coating the plate with platinum black. The coat ing is effected by passing an electric current first one way and then the other between two platinum plates immersed in a 3% solution of platinum chloride to which a trace of lead acetate is sometimes added. The platinized plates thus obtained are quite satisfactory for the investigation of strong solutions. They have the power, however, of absorbing a certain amount of salt from the solutions and of giving it up again when water or more dilute solution is placed in contact with them. The measurement of very dilute solutions is thus made difficult, but if the plates be heated to redness after being platinized a grey surface is obtained which possesses sufficient area for use with dilute solutions and yet does not absorb an appreciable quantity of salt.

Any convenient source of alternating current may be used. The currents from the secondary circuit of a small induction coil from which the condenser has been removed are satisfactory for most purposes. With such currents it is necessary to consider the effects of self-induction in the circuit and of electrostatic capacity. In balancing the resistance of the electrolyte, resistance coils may be used in which self-induction and the capacity are reduced to a minimum by winding the wire of the coil backwards and forwards in alternate layers.

With these arrangements the usual method of measuring re sistance by means of Wheatstone's bridge may be adapted to the case of electrolytes. With alternating currents, however, it is im possible to use a galvanometer in the usual way. The galvano meter was therefore replaced by Kohlrausch by a telephone, which gives a sound when an alternating cur rent passes through it. The most common plan of the apparatus is shown diagram matically in fig. (I). The electrolytic cell and a resistance box form two arms of the bridge, and the sliding contact is moved along the metre wire which forms the other two arms till no sound, or only a minimum sound, is heard in the telephone. The posi tion of minimum sound is more sharply obtained by connecting a variable air con denser in parallel with the conductance cell so as to balance its capacity. The resistance of the electrolyte is to that of the box as that of the right-hand end of the wire is to that of the left-hand end. A more accurate method of using alternating currents dispenses with the telephone (Phil. Trans., 1900, P. 32I). The current from one or two voltaic cells is led to an ebonite drum turned by a motor or a hand-wheel. On the drum are fixed brass strips with wire brushes touching them in such a manner that the current from the brushes is reversed several times in each revolution of the drum. The wires from the brushes are connected with the Wheatstone's bridge. A moving coil galvanometer is used as indicator, its connections being re versed in time with those of the battery by a slightly narrower set of brass strips fixed on the other end of the ebonite com mutator. Thus any residual current through the galvanometer is direct and not alternating. The high moment of inertia of the coil makes the period of swing slow compared with the period of alternation of the current, and the slight periodic disturbances are thus prevented from affecting the galvanometer. When the measured resistance is not altered by increasing the speed of the commutator or changing the ratio of the arms of the bridge, the disturbing effects may be considered to be eliminated.

The form of vessel chosen to contain the electrolyte depends on the order of resistance to be measured.

For dilute solutions the shape of cell shown in fig. (2) will be found convenient, while for more concentrated solutions, that in dicated in fig. (3) is suitable. The absolute resistances of certain solutions have been determined by Kohlrausch by comparison with mercury, and, by using one of these solutions in any cell, the constant of that cell may be found once for all. From the observed resistance of any given solution in the cell the resistance of a centimetre cube —the so-called specific resistance—may be calculated. The recip rocal of this, or the conductivity, is a more generally useful con stant ; it is conveniently expressed in terms of a unit equal to the reciprocal of an ohm. Thus Kohlrausch found that a solution of potassium chloride, containing one-tenth of a gram equivalent grams) per litre, has at 18° C a specific resistance of 89.37 ohms per cm. cube, or a conductivity of I • I I 9 X ohms or 1.119X Io c.g.s. units. As temperature variation of conductiv ity is large, usually about 2% per degree, it is necessary to place the resistance cell in a paraffin or water bath, and to observe its temperature with some accuracy.

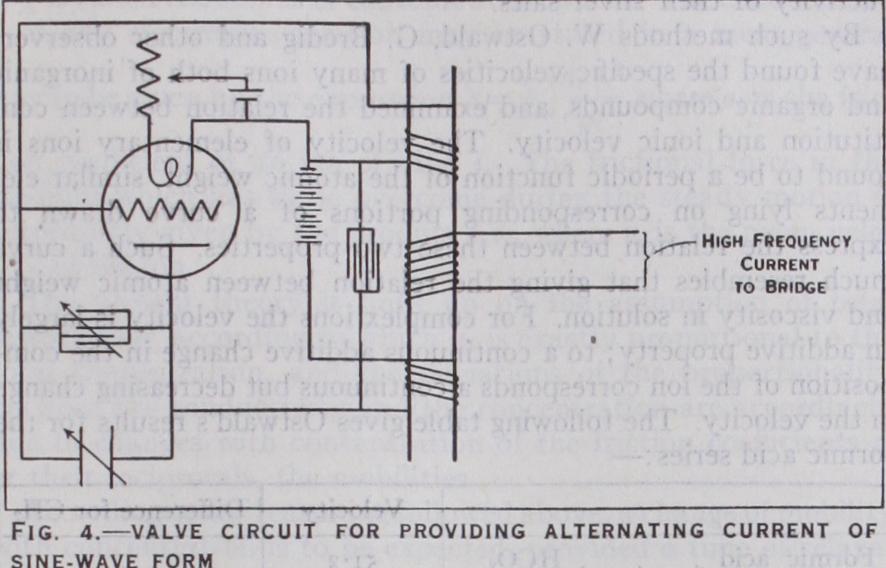

An important objection to the use of the induction coil for accurate measurements is that it does not give a current of zero integral value, i.e., the current is not alternating, but pulsating, having a uni-directional component. Another objection to this instrument is the difficulty of maintaining the frequency constant. A motor-driven small high frequency generator such as the Vree land oscillator has been applied for conductance measurements. The most satisfactory source of alternating current for con ductivity measurements is that provided by a thermionic value oscillator which gives a pure sine wave. The arrangement em ployed is illustrated in fig. (4). The frequency of the wave is varied by altering the capacity of the condenser C, which is of small capacity and continuously variable over its entire range and the condenser C' which is variable in steps of say 0.005 microfarad. Currents of from a few tenths to 25 amperes and having a frequency ranging from one-half to 5 X I cycles may be obtained from this type of generator.

A principle employing direct current was adopted by E. Bouty in 1884 (cf. also Marie and W. A. Noyes fount. Amer. Chem. Soc., 1921). If a current be passed through two resistances in series by means of an applied electromotive force, the electric potential falls from one end of the resistances to the other, and, if Ohm's law be applied to each resistance in succession, it is seen that, since for each of them E = IR, and I the current is the same through both, E, the elec tromotive force or fall of poten tial between the ends of each resistance, must be proportional to the resistance between them. Thus by measuring the potential dif ference between the ends of the two resistances successively, their resistances may be compared. If, on the other hand, the potential differences are measured in some known units, and, similarly, the current flowing, the resistance of a single electrolyte can be determined.

Equivalent Conductivity of Solutions.

The foundation of this knowledge was laid by Kohlrausch when he had developed the method of measuring electrolyte resistance described above. He expressed his results in terms of equivalent conductivity, i.e., the conductivity (K) of the solution divided by the number (m) of gram-equivalents of electrolyte per litre. He found that, as the concentration diminishes, the value of rc/m approaches a limit, and eventually becomes constant, that is to say, at great dilution the conductivity is proportional to the concentration. Kohlrausch first prepared very pure water by repeated distilla tion and found that its resistance continually increased as the process of purification proceeded. The conductivity of the water, and of the slight impurities which must always remain, was sub tracted from that of the solution made with it, and the result, divided by m, gave the equivalent conductivity of the substance dissolved. This procedure appears justifiable, for as long as con ductivity is proportional to concentration it is evident that each part of the dissolved matter produces its own independent effect, so that the total conductivity is the sum of the conductivities of the parts ; when this ceases to hold, the concentration of the solu tion has in general become so great that the conductivity of the solvent may be neglected. The general result of these experiments can be represented graphically by plotting K/m as ordinates and to as abscissae, in being a number proportional to the re ciprocal of the average distance between the molecules, to which it seems likely that the molecular conductivity may be related. The general types of curve for a simple neutral salt like potassium or sodium chloride and for a caustic alkali or acid are shown in fig. (5) . The curve for the neutral salt reaches to a limiting value; that for the acid attains a maximum at a certain very small con centration, and falls again when the dilution is carried farther. The values of the molecular conductivities of all neutral salts are, at great dilution, of the same order of magnitude, while those of acids at their maxima are about three times as large. The influence of increasing concentration is greater with salts containing divalent ions, and greatest of all in solutions such as those of ammonia and acetic acid, which are substances of very low conductivity.

Theory of Moving Ions.

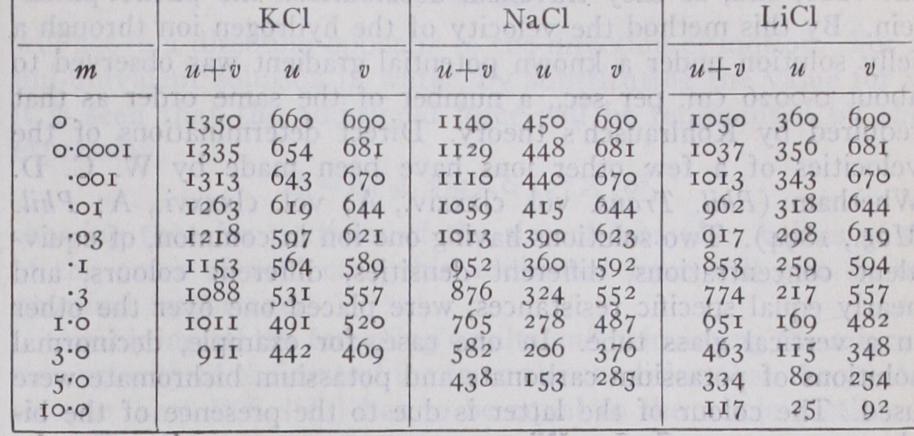

The quan tity of electricity flowing per second, i.e., the current through the solution, depends on (1) the number of the ions concerned, (2) the charge on each ion, and (3) the velocity with which the ions travel past each other. Now, the number of ions is given by the concentration of the solu tion, for even if all the ions are not actively engaged in carrying the current at the same instant, they must, on any dynami cal idea of chemical equilibrium, be all active in turn. The charge on each can be expressed in absolute units, and therefore the velocity with which they move past each other can be cal culated. This was first done by Kohlrausch (Gottingen Nachrich ten, 1876, and Das Leitvermogen der Elektrolyte, Leipzig, 1898). By combining the results of determinations of transport numbers by Hittorf's method with the sum of the velocities, as determined from the conductivities, Kohlrausch calculated the absolute veloc ities of different ions under stated conditions. The table shows Kohlrausch's values fo_r the ionic velocities of three chlorides of alkali metals at 18° C, calculated for a potential gradient of 1 volt per cm. u is the velocity of the positive ion, v that of the nega tive ion; the numbers are in terms of a unit equal to cm. per sec.: These numbers show clearly that there is an increase in ionic velocity as the dilution proceeds. Moreover, if we compare the values for the chlorine ion obtained from observations on these three different salts, we see that as the concentrations diminish the velocity of the chlorine ion becomes the same in all of them. A similar relation appears in other cases, and, in general, it may be said that at great dilution the velocity of an ion is independent of the nature of the other ion present. This introduces the con ception of specific ionic velocities, for which some values at 18° C are given by Kohlrausch in the following table : From these numbers can be deduced the conductivity of the dilute solution of any salt, and it was a comparison of the cal culated with the observed values that furnished the first confirma tion of Kohlrausch's theory. Some exceptions, however, are known. Thus acetic acid and ammonia give solutions of much lower con ductivity than is indicated by the sum of the specific ionic veloci ties of their ions as determined from other compounds. An at tempt to find in Kohlrausch's theory some explanation of this discrepancy shows that it could be due to one of two causes. Either the velocities of the ions must be much less in these solu tions than in others, or else only a fractional part of the number of molecules present can be actively concerned in conveying the current. This point will again be considered later.

Friction on the Ions.

It is interesting to calculate the mag nitude of the forces required to drive the ions with a certain velocity. A potential gradient of i volt per cm. leads to an elec tric force of in c.g.s. units. The charge of electricity on i gram-equivalent of any ion is 1/•0001036=9653 units, hence the mechanical force acting on this mass is 9653X dynes. Suppose this produces a velocity u; then the force required to produce unit velocity is Pa= 9653X Io" dynes = 9.84X To' kg.–weight. u u If the ion have an equivalent weight A, then the force producing unit of velocity when acting on I gram is 6 9.84 X Au kg.–weight.Thus, A being 39.1 and u being 660X for potassium, the aggregate force required to drive 1 gram of potassium ions with a velocity of 1 cm. per second through a very dilute solution must be equal to the weight of 38X kilograms.

Direct Measurement of Ionic Velocities.

Sir Oliver Lodge was the first to measure directly the velocity of an ion (Brit. Ass. Report, 1886). In a horizontal glass tube connecting two vessels filled with dilute sulphuric acid he placed a solution of sodium chloride in solid agar-agar jelly. This solid solution was made alkaline with a trace of caustic soda in order to bring out the red colour of a little phenolphthalein added as indicator. An electric current was then passed from one vessel to the other. The hydro gen ions from the anode vessel of acid were thus carried along the tube, and, as they travelled, decolourized the phenol-phtha lein. By this method the velocity of the hydrogen ion through a jelly solution under a known potential gradient was observed to about 0.0026 cm. per sec., a number of the same order as that required by Kohlrausch's theory. Direct determinations of the velocities of a few other ions have been made by W. C. D. Whetham (Phil. Trans. vol. clxxxiv., A; vol. clxxxvi., A; Phil. Mag., 1894). Two solutions having one ion in common, of equiv alent concentrations, different densities, different colours, and nearly equal specific resistances, were placed one over the other in a vertical glass tube. In one case, for example, decinormal solutions of potassium carbonate and potassium bichromate were used. The colour of the latter is due to the presence of the bi chromate group, When a current was passed across the junction, the anions CO3' and travelled in the direction opposite to that of the current, and their velocity could be deter mined by measuring the rate at which the colour boundary moved. Similar experiments were made with alcoholic solutions of cobalt salts, in which the velocities of the ions were found to be much less than in water.The behaviour of agar jelly was then investigated, and the velocity of an ion through a solid jelly was shown to be very little less than in an ordinary liquid solution. The velocities could therefore be measured by tracing the change in colour of an indicator or the formation of a precipitate. Thus decinormal jelly solutions of barium chloride and sodium chloride, the latter containing a trace of sodium sulphate, were placed in contact. Under the influence of an electromotive force the barium ions moved up the tube, disclosing their presence by the trace of in soluble barium sulphate formed. Again, a measurement of the velocity of the hydrogen, when travelling through the solution of an acetate, showed that its velocity was then only about the one fortieth part of that found during its passage through chlorides. From this, as from the measurements on alcohol solutions, it is clear that where the equivalent conductivities are very low the effective velocities of the ions are reduced in the same proportion.

Another series of direct measurements has been made by Orme Masson (Phil. Trans., vol. cxcii., A). He placed the gelatine solu tion of a salt, potassium chloride, for example, in a horizontal glass tube, and found the rate of migration of the potassium and chlorine ions by observing the speed at which they were replaced when a coloured anion, say, the from a solution of potas sium bichromate, entered the tube at one end, and a coloured cation, say, the Cu from copper sulphate, at the other. The col oured ions are specifically slower than the colourless ions which they follow, and in this case it follows that the coloured solution has a higher resistance than the colourless. For the same current, therefore, the potential gradient is higher in the coloured solution and lower in the colourless one. Thus a coloured ion which passes in front of the advancing boundary finds itself acted on by a smaller force and falls back into line, while a straggling colourless ion is pushed forward again. Hence a sharp boundary is preserved. B. D. Steele has shown that with these sharp boundaries the use of coloured ions is unnecessary, the junction line being visible owing to the difference in the optical refractive indices of two colourless solutions. Once the boundary is formed, too, no gela tine is necessary, and the motion can be watched through liquid aqueous solutions. (See R. B. Denison and B. D. Steele, Phil. Trans., 1906.) All the direct measurements which have been made on simple binary electrolytes agree with Kohlrausch's results within the limits of experimental error. His theory, therefore, probably holds good in such cases, whatever be the solvent, if the proper values are given to the ionic velocities, i.e., the values expressing the velocities with which the ions actually move in the solution of the strength taken, and under the conditions of the experiment. If the specific velocity of any one ion is known, it is possible to deduce, from the conductivity of very dilute solutions, the veloc ity of any other ion with which it may be associated, a proceeding which does not involve the difficult task of determining the mi gration constant of the compound. Thus, taking the specific ionic velocity of hydrogen as 0.00032 cm. per sec., by determining the conductivity of dilute solutions of any acid, the specific velocity of the acid radicle involved can be found. Or again, since the specific velocity of silver is known, the velocities of a series of acid radicles at great dilution can be found by measuring the con ductivity of their silver salts.

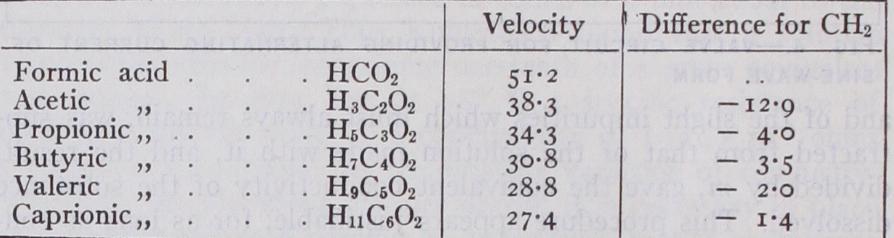

By such methods W. Ostwald, G. Bredig and other observers have found the specific velocities of many ions both of inorganic and organic compounds, and examined the relation between con stitution and ionic velocity. The velocity of elementary ions is found to be a periodic function of the atomic weight, similar ele ments lying on corresponding portions of a curve drawn to express the relation between these two properties. Such a curve much resembles that giving the relation between atomic weight and viscosity in solution. For complex ions the velocity is largely an additive property ; to a continuous additive change in the com position of the ion corresponds a continuous but decreasing change in the velocity. The following table gives Ostwald's results for the formic acid series :— The Theory of Debye and Hiickel.—In the investigations of Debye and Mickel a theory has been developed which though not complete may be considered to have furnished already for dilute solutions of strong electrolytes a complete explanation of the main properties (Phys. Zeits. 1924; Trans. Faraday Soc., 1927; see also ELECTROLYSIS for the bearing of this theory on the activity of an electrolyte). In this theory, which assumes complete dis sociation of strong electrolytes, the view has been developed that the fall of molecular conductivity observed with increasing con centration is due not to a diminution of the number of ions but to a reduction of their mobility on account of electrostatic forces. The electrostatic potential at the surface of the ion induces an ionic atmosphere of opposite charge, the density of which de creases with increasing distance from the centre of the ion. In the equilibrium condition the ionic atmosphere will possess cen tral symmetry, but on subjecting an electrolyte to an external field so as to generate a current and a mean movement of each ion in one direction the central symmetry of the ionic system will be destroyed. If, for instance, the central ion moves to the right, then during its motion it will constantly have to build up a charge density constituting its atmosphere to the right, whereas to the left the charge density will have to die out. If the creation of the ionic atmosphere could be accomplished instantaneously, no effect of the motion would be perceptible. If, however, a finite time of relaxation exists, during the motion of the central ion the atmosphere will, in the right-hand part, never reach its equilibrium density, whereas in the left-hand part the density will constantly be larger than its equilibrium value. Since the charge density in the atmosphere always has a sign opposite to the charge of the ion, it follows that, owing to the dissymmetry of its atmosphere, the central ion will be acted upon by a force tending to decrease its velocity. As the amount of dissymmetry increases with increasing velocity, this force will also increase, so that it will have the same effect that an increase of the friction constant would have. It is shown by Debye and Mickel that the decrease of density of the ionic atmosphere with distance is given by the exponential where r is the distance and x has the dimensions of a reciprocal length denoting the distance at which the charge density has fallen to i/€ of its initial value.

It can be shown (cf. ELECTROLYSIS) that x is given by the equation when D= dielectric constant of the solvent, k =1-37 X io ls= Boltz mann's constant, T = absolute temperature, n, = number of ions of kind i in I c.c., = charge of one ion of kind i. For a univalent electrolyte of concentration m calculated in mols. per litre and in the solvent water, it is found IO'Vm or I/X=3•o6X I/X is called the radius of the ionic atmosphere. The X of any electrolyte solution may be stated in a most general n, E,= way to be given by the expression X = E where is the fric P: tion coefficient of an ion of kind i. The frictional force in the medium which has to be overcome during the steady motion is accordingly given by the product where is the mean velo city of the ion.

The present theory is built up on the assumption of total

dissociation, according to which is exactly proportional to the total concentration, and the deviations of the proportionality between the conductivity and the concentration are accordingly due to changes with concentration of the friction coefficients or their reciprocals, the mobilities.

According to the reasoning followed above, a change of mobility

with concentration is to be expected, provided a time of relaxa tion characteristic of the ionic atmosphere exists. An expression is developed for the space distribution of ions, allowing for its variation in time by supposing a total central charge E in equilibrium with its ionic atmosphere to be destroyed at the instant t= o and determining how the charge density of the atmosphere spreads out to zero density. A mathematical ex pression is thus derived for the charge density, or the potential, as a function of the distance from the centre r and the time 1. An essential time constant r governing the decrease and known as the time of relaxation is derived. In the case of an electrolyte with two univalent ions of equal mobility (like KC1) z is given by the expression __ T X2kT • For a KC1 solution of m mols per litre, this gives r= 0.55 Io-10 sec. m When an ion moves with a given constant velocity in the direction of the external field, the additional field intensity in the direction opposite to the motion of the central ion is given by the expression = I E XP v. 6 D kT where E is the total charge of the central ion and p is the mean friction coefficient of the solution.

For a solution in which the ions have equal mobilities the

additional force or product of the ionic charge and the additional field intensity is given by the expression Ro — 6DkT where = pv is the frictional force on a central ion in an in finitely dilute solution. For a KCl solution in water of concen tration m mols. per litre, this additional force has the absolute value showing that the effect is of practical importance. In an infinitely dilute solution, P may be used to represent the frictional constant so that in this case = Pv.

In Stokes formula, the frictional force is given by the expression

= 67rrtCv where C is the radius of the moving sphere and the internal friction constant of the liquid. In this formula it is supposed that no external force acts on the liquid surround ing the sphere. In the present case however the external field will also act on the charges constituting the atmosphere in accordance with the principle of electrophoresis, the relations of which have been calculated by Helmholtz. The charges in the liquid and the charge of the sphere always have opposite sign. The additional motion due to the existence of these charges will therefore have a velocity oppositely directed to the velocity of the particle. It follows that, in addition to the Stokes force, an additional force will act in a direction opposite to the direction of motion. For a uni-univalent solution in water, by substituting the value for X it is seen that the additional force will be represented by the expression X o•3 2 7 X showing that for particles of the size of ions (i.e., values of C of the order of cm.) this additional force will also be of practical importance.Combining all the foregoing results and calculating the migra tion velocity of the central ion from the condition that the whole electric force has to be equal to the whole frictional force we have Hence it follows that the migration velocity of an ion with charge E and the frictional constant P should be represented by the formula v _ — P EFo L P E2X 11 2 X P 6Dk P I +, pX P 6DkT According to this formula the correction of the migration velocity in infinite dilution is proportional to x (the reciprocal of the radius of the ionic layer) and therefore proportional to the square root of the concentration.

In the case of a uni-univalent electrolyte, calling

the limiting value of the molar conductivity at infinite dilution and A the molar conductivity at a certain small concentration, the theory leads from the above expressions for the migration velocity to the formula where pi and are frictional coefficients for anion and cation respectively. Substituting numerical values for solutions in water at 18°C. we have l = o•233 X Io8 Cip2+ C2P1 +° 273 C 2 J Ao P1P2 It is possible to avoid the introduction of the ionic radii and C2 by taking in accordance with Stokes formula, P1 = 67rt P2= and taking ii as the ordinary viscosity of the liquid. Performing this elimination gives the formula A_ r I NE2 + P12+P22 E2 0 3 ' 1 X A L 2r P 21P2 6DkTJ in which N =6-o6 X Ion= Avagadro's number, or substituting numerical values, Ao—A ! C + 0'273 2 J V2m.

AO AO

P1P2 This expression can also be written in the following form which is applicable to all solvents (K1 2m, A D= D 0 where w1 = Z + ' and and K2 are universal constants 1, varying only with the temperature 1, and the mobilities of the cation and anion b the harmonic mean of the ionic radii and c the molecular concentration.

It is pointed out by Onsager

(Trans. Faraday Soc. 1927) that on account of the Brownian movements of the central ion the value of the additional force due to the dissymmetry of the ionic atmosphere has to be corrected. If the mobili,Jies of the two ions are equal, his correction factor has the value 2 = o.586. Introducing this correction the theoretical expression in the case of KCl = becomes which gives for =129.9 the value of 0•433 for the factor which is close to its experimental value 0•461. It has been shown that these equations are in good agreement with the best conductivity data for aqueous solutions; and data compiled by H. Hartley and R. P. Bell (Trans. Faraday Soc., 1927) of conductivity measurements in a large number of solvents show a general agree ment in many cases with the above expressions. In other in stances, however, deviations occur which appear to be due to the formation of complexes or else to lack of complete ionization of the electrolyte. In general the evidence obtained thus so far agrees so well with the theory that it seems reasonable to accept the assumption that typical strong electrolytes (salts) are practically completely dissociated at all concentrations, at least in solvents of high dielectric constant, though this theory of complete dis sociation fails to cover the behaviour of those weak electrolytes which obey Ostwald's dilution law (see ELECTROLYSIS) just as completely as this latter law fails to cover the behaviour of highly dissociated metallic salts.BIBLIOGRAPHY.-F. Kohlrausch and L. Holborn, Das Leitvermogen Bibliography.-F. Kohlrausch and L. Holborn, Das Leitvermogen der Elektrolyte (Leipzig, 1898) ; W. C. D. Whetham, The Theory of Solutions and Electrolysis (1902) ; Kraus, The Properties of Electri cally Conducting Systems (192 2) ; Creighton and Fink, Electro chemistry (1924). See also ELECTROLYSIS. (J. N. P.)