Conduction of Electricity

ELECTRICITY, CONDUCTION OF. The mechanism of the conduction of electricity is markedly different in solids, liquids and gases, which are accordingly dealt with separately.

The electric conductivity of a substance is that property in which electricity is transferred through the substance if an electric poten tial difference is applied to two parts thereof. A substance in which unit quantity of electricity is transferred through unit cross section under the influence of unit potential gradient is said to have unit conductivity. The reciprocal quantity is the electric resistance which may be defined in a similar way. A priori the quantity of electricity transferred for a given potential gradient might well depend upon how long the current had been flowing. The concepts, electrical conductivity and electrical resistance, would probably never have been formed were it not that there is a large class of substances for which the conductivity is determined completely by the conditions of the moment and is independent of the previous history of the conductor. Strictly speaking, it is for these only that the terms conductivity and resistance have any validity. All substances conduct electricity to a greater or smaller degree. For the purpose of description, it is convenient to divide solids into three classes, namely, metallic conductors, non-metallic conductors and dielectrics although there are no precise lines of demarcation.

Metallic Conductors.

The main characteristics of a metal are its high electric conductivity and consequent opacity, its good heat conductivity, its tendency to form positive ions in solution and its inability to form a simple solution in non-metals. All these properties are consequences of the ease with which the atoms of a metal can lose or dissociate electrons. When in the vapour phase the atoms are far apart and electrons dissociate appreciably only at comparatively high temperatures such as the surface of the sun or stars. But when the atoms are packed close together as in solid metals, polarization comes into play so that it is easier for an electron to escape from its parent atom. That the current is carried through a metal by these free electrons has been proved. That they can also transfer heat is an extremely important phenomenon, the explanation of which is not so apparent.

Resistivity of Metallic Conductors.

The resistance of a conductor depends of course upon its shape as well as upon the material of which it is composed. The effect of shape can be eliminated and the specific resistance of the material, i.e., the resistance of unit cube, can be obtained provided Ohm's Law, that the current is proportional to the applied voltage, and in versely proportional to the resistance, is satisfied. In metals, Ohm's Law is fulfilled to a very high degree of accuracy; slight deviations have, however, been found at excessively high current densities. If a current of the order five million amperes per square centimetre is made to flow through a thin film of silver or gold, the departure from Ohm's Law may amount to some thing of the order of one per cent. Strictly speaking therefore, the definition of the specific resistance should include the current density, but in metals at any rate, Ohm's Law is valid over such an enormous range that this can be omitted. If a conductor is of uniform cross-section and of homogeneous material, the potential gradient must be uniform, since the current flowing through every cross-section must clearly be the same. It has been shown that the resistance of such conductors is inversely proportional to their cross-sections. Hence, in this simple case, it is easy to derive the specific resistance from the resistance of the conductor. It is obviously the observed resistance divided by the length in centimetres and multiplied by the cross-section in square centi metres. Thus, a wire one metre long and of a cross-section of one square millimetre, will have a resistance 10,000 times greater than the specific resistance of the material of which it is com posed, or inversely, the specific resistance of the material is one ten-thousandth of the observed resistance of such a wire. If the shape is not so simple, the transition from observed resist ance to specific resistance is, of course, much more complicated, since the potential gradient will vary along the conductor. The resistance of a metallic conductor is within wide limits inde pendent of the time. It has been shown that the reflection co efficient of metals for infra-red rays may be calculated from the resistance if one treats the incident radiation as an alternating field as postulated by the electromagnetic theory. That this relation breaks down at frequences of the order i.e., for currents which change their direction in seconds, is scarcely surprising. It indicates merely, that the resistance to the motion of the electrons is composed of a number of elementary processes at intervals which are not short compared to seconds.

International Ohm.

The practical unit of electrical resist ance was legally defined in Great Britain by the authority of the Queen in council in 1894, as the "resistance offered to an invari able electric current by a column of mercury at the temperature of melting ice, 14.4521 grammes in mass, of a constant cross-sec tional area, and a length 106.3 centimetres." The same unit has been also legalized as a standard in France, Germany, and the United States and is denominated the "International or Standard Ohm." It is intended to represent as nearly as possible a resist ance equal to absolute C.G.S. units of electrical resistance. Convenient sub-divisions and multiples of the Ohm, are the microhm and the megohm, the former being a millionth part of an Ohm, and the latter a million Ohms. The resistivity of sub stances is then numerically expressed by stating the resistance of one cubic centimetre of the substance taken between opposed faces, and expressed in Ohms, microhms or megohms, as may be most convenient. The reciprocal of the Ohm is called the Mho, which is the unit of conductivity, and is defined as the conduc tivity of a substance whose resistance is one Ohm. The absolute unit of conductivity is the conductivity of a substance whose resistivity is one absolute C.G.S. unit, or one-thousandth-millionth part of an Ohm.Besides this so-called volume-resistivity, a quantity is some times employed, called the mass-resistivity, defined as the resist ance in ohms of a wire of the material in question of uniform cross-section one metre in length, and one gramme in weight. This quantity is of small scientific interest, though convenient in some cases for technical purposes when the weight of a conductor, capable of carrying a given current at a given voltage, is of importance. The mass-resistivity so defined, is the volume resistivity multiplied by the density times A quantity of far greater importance, for the understanding of the cause of metallic resistance, may be described as the atomic-resistivity. Since one is only concerned with comparative quantities the units are of course immaterial, but it might be conveniently described as the resistance for unit potential differ ence of a cube containing Avogadro's number of atoms. This quantity refers to the electrical characteristics of the metal in comparable circumstances, i.e., there are the same number of atoms in cross-section in each case, and the potential drop per atom is the same. It may be obtained from the usual volume resistivity, by multiplying by the third root of the density and dividing by the third root of the atomic weight. Table I. gives a list of the commoner metals with their volume-resistivity, mass resistivity and atomic-resistivity at 18° C. The values are given in ohms : they can be translated into absolute C.G.S. units by multiplying by 509.

Nom: The resistance of a metal varies according to its previous his tory, i.e., whether it has been rolled, drawn, cast, etc., and also accord ing to its purity, a small trace of impurity in many cases increasing the resistance by 2o%. Therefore in actual practice variations of io% in the above values may be expected.

C. to .

melting point.The figures of course refer to normal polycrystalline metals. Single crystals may have a higher conductivity, e.g., in copper there is a difference of about 8%. In non-cubic crystals the con ductivity also varies with the orientation, as will be seen a most important and suggestive phenomenon. It will be noted that the volume-resistivity of the metals in the first group of the periodic table, is lower than that of any of the others. The transition elements, like bismuth and antimony, have an abnormally high resistance, but no clear connection between the resistivity and the other characteristics of the metals is immediately discoverable. This can scarcely cause surprise, since the metals are not in com parable condition as regards temperature. Comparable tempera tures, according to modern theories of specific heat, would be those in which the amplitudes of oscillation of the atoms, were in all cases an equal fraction of the distance between them. If the atomic-resistivity is reduced to corresponding temperatures, as exhibited in the last column of the table, one sees a certain regularity emerge.

So far attention has been directed exclusively to pure metals. the resistance of alloys is a very complicated matter. In the ase of those alloys, which do not form solid solutions and which onsist really simply of a mixture of two or more metals, the pecific conductivity, as might be expected, is proportional to the volume composition of the alloy. The conductor is merely an Lggregate of small conductors consisting of pure metals. The 'esistivity is a much more complicated matter in those cases, n which one metal is in solid solution, in the other, i.e., in which he crystal structure is retained, and the atoms of one metal are by atoms of the other in the space-lattice. The admix ure of the second component raises the resistivity, and if the wo metals form a continuous solid solution, one finds in general n a binary alloy a continuous curve rising fairly sharply at either of the scale with a flat maximum between the two pure netals. The effect of different metals upon the electrical resist ince is very varied. Thus the addition of i % of silver to copper, ;hanges its resistivity by an amount variously estimated at 7 to [2 per cent, whereas one percent of zinc changes it by 15 to 17, in 145, chromium 220 and antimony 310 to 420 per cent. In ;eneral it would seem that the effect is greater the further the solvent and solute metals are apart in the periodic table, but his can only be regarded as an empirical rule which may have a :ertain technical interest when the effect of impurities is at issue. Temperature.—One of the most important factors affecting he electrical resistance is the temperature. If one plots the resistance of a pure metal as a function of the temperature, it may be represented roughly as a straight line pointed at the origin, in other words, the resistance may be represented as a very rough approximation, by the expression const. T. This sig nificant fact is only the first which emerges. A closer examination reveals that this expression is only a first approximation and repre sented more accurately by the expression const.U,U representing the internal energy of the metal. The internal energy is the integral of the atomic heat, so that if this formula were accurate the temperature coefficient of the resistance should be proportional to the atomic heat. It has been shown that the atomic heats of the elements, which according to Dulong and Petit's law, should be constant and equal to about six calories, may in reality be represented with much more accuracy by a complicated, but general function of the temperature divided by a characteristic temperature pertaining to each individual metal. (See QUANTUM THEORY.) At high temperatures this function approaches asymp totically the value 3 R demanded by Dulong and Petit. At temperatures of the order of the characteristic temperature, the atomic heat falls well below 3 R and approaches zero as the absolute zero of temperature is reached. Metals with a high melting point, i.e., strong inter-atomic forces and low atomic weights, such as aluminium or copper, have comparatively high characteristic temperatures, whilst metals with a low melting point and large atomic weights, such as lead or mercury have low characteristic temperatures. Thus in the first class, the atomic heat falls considerably below 3 R at comparatively high tem peratures (Ioo° to 200° absolute) whilst in the latter class the atomic heat remains constant down to much lower temperatures (20° to 40° absolute). The temperature coefficient of the resist ance shows the same characteristics. Constant, in the case of copper and aluminium down to ioo° to 200° absolute, at these temperatures it commences to fall whereas, in the case of lead or mercury it remains constant down to 20 or 4o degrees of the absolute zero. This very striking fact is often masked by the presence of slight impurities. As was pointed out above, these usually have the effect of increasing the resistance. The added resistance due to the impurity, is not subject in the same way to the effect of temperature. As a first approximation, it may be treated as a constant so that the resistance of a metal may be represented roughly as composed of two terms, one small and constant, probably due to the presence of impurities, and the other rising according to the universal function of the temperature, which presents the internal energy of the metal.

The fact that the added resistance due to the alloying metals does not vary greatly with the temperature, has been made use of by employing alloys of special composition for standards of resistance and other similar purposes. When the main resistance is the alloy resistance, as for instance occurs when the metals which conduct well individually, are dissolved in one another, the constant term is large compared to the term which represents the resistance as a function to the temperature and the total resistance may be almost independent of temperature.

A very remarkable phenomenon has been observed in the case of some metals whose resistance has been measured at extremely low temperatures. Observed to be normal down to the vicinity of about 5° absolute, the resistance already small, but easily measur able, diminishes suddenly to an imperceptible quantity. In the case of lead for instance, it has been shown that the resistance below the critical temperature is less than i of its value at zero centigrade. So small is the resistance in this state, that a current started in a ring, induced say by removing a magnet from the centre, will continue to flow for months without appreciable diminution. This so-called supra-conductivity is a quite distinct phenomenon which has only been observed in the case of certain metals. At first sight, it might appear that its absence in the case of other metals might be due to some small impurity, which gives the metal a small alloy resistance unaffected by temperature. This does not seem to be the true explanation, for supra-conduc tivity has been looked for in vain in gold which can be obtained relatively pure, whilst it has been found in such metals as tin and lead which are much more likely to contain traces of im purities. Table II. gives a list of those metals in which supra conductivity has been observed and the temperatures at which it appears.

A most important fact that emerges is that supra-conductivity sets in at an extremely well marked and definite temperature. It can be destroyed by the application of an external magnetic field to reappear as the temperature is lowered; this is not altogether surprising seeing that an electrical current must be due to the motion of electric charges, when one considers the curvature of the path of a moving charge produced by a mag netic field.

Pressure.

The effect of pressure upon the electrical resist ; ance of metals is usually slight. In a great majority of cases it diminishes the resistance, but in a few, namely, Lithium, Caesium, Calcium, Strontium, Antimony and Bismuth, the resist ance increases as the pressure is raised. Caesium occupies a special position as the only metal in which the resistance first increases and afterwards decreases with rising pressure, a condition which has been sought, but not found in any other metal. At first sight it might seem surprising that an increase of pressure which corresponds to a decrease in volume, should facilitate the flow of electrons through the metal. Even taking into account that the specific resistance is the resistance of unit volume, so that the increase of pressure with the accompanying contraction corresponds to an increase in the number of atoms and therefore, of electrons in unit volume, the conductivity often increases. Since one has an effect compounded of the variation in the perme ability of the metal for electricity and the change in the number of electrons in unit volume owing to the increase in density, simple results can scarcely be expected. The effects are in all cases small, being of the order of the change in volume, i.e., the fractional change of resistance is of the order Io 12 or io 11 per dyne.

Stress.

Still more complicated are the effects of stress and deformation on the electrical resistance. These are of a similar order of magnitude to those due to pressure as long as the deformations are within the elastic limit. When greater deforma tions are produced, considerably greater changes are caused and variations up to as much as 8% have been observed on working some of the pure metals. The same applies to the temperature coefficients, but all these effects may be annulled by annealing the metal, when recrystallization takes place and it returns to its original unstrained condition.

Magnetic Field.

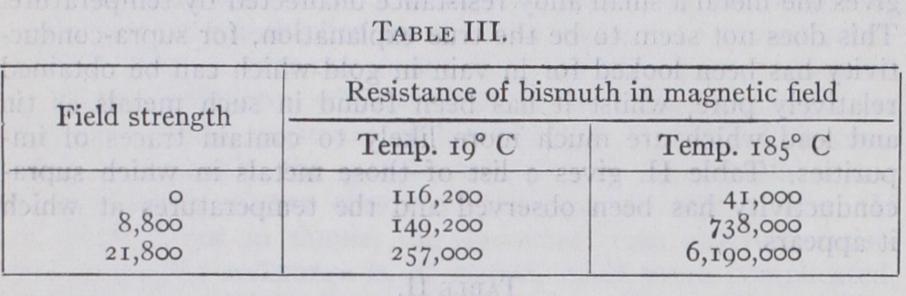

The effect of a magnetic field upon the conductivity of a metal shows itself in various ways. The so called longitudinal Hall effect, is the name given to the change in the resistance which occurs in the magnetic field. For all except magnetic metals (iron, nickel and cobalt) the resistance increases, the amount however, being of the order of •o i % for a field of ten thousand C.G.S. units. In bismuth a comparatively enormous effect is observed, so much so, that the resistance of spirals of thin metal bismuth wire is used for measuring mag netic fields. The order of magnitude of the effect is shown in table III., and it will be noted that it increases very much at low temperatures. It is probable that this effect is a secondary one, due to the presence of microscopic cracks which expand under the influence of the field.

Allied Effects.

Four lateral effects caused by the magnetic field correspond to the lateral displacement of a moving elec trical charge. The Hall effect may be described as the potential difference produced on the two edges of an elongated metallic plate through which a current is flowing when placed in a mag netic field at right angles to it. The magnitude varies from metal to metal, and is in general small, but no relation has as yet been discovered which enables one to predict either its magni tude or even its sign.The Ettinghausen effect is the name given to the temperature difference produced on the two edges on an elongated metal plate through which a current is flowing by the application of a mag netic field at right angles to it. It analogizes to the Hall effect, except that a temperature difference is observed in place of a potential difference.

The two other transverse effects correspond to the above, ex cept that a current of heat replaces the electric current. The Nernst effect expresses the fact that a potential difference is observed between the edges of an elongated plate down which heat is flowing when it is placed in a magnetic field. The Righi Leduc effect corresponds to the temperature difference observed on the edges in similar circumstances. All these effects are very slight in the case of the normal metals, but are much greater in the case of elements such as antimony and bismuth, in which non metallic properties begin to appear.

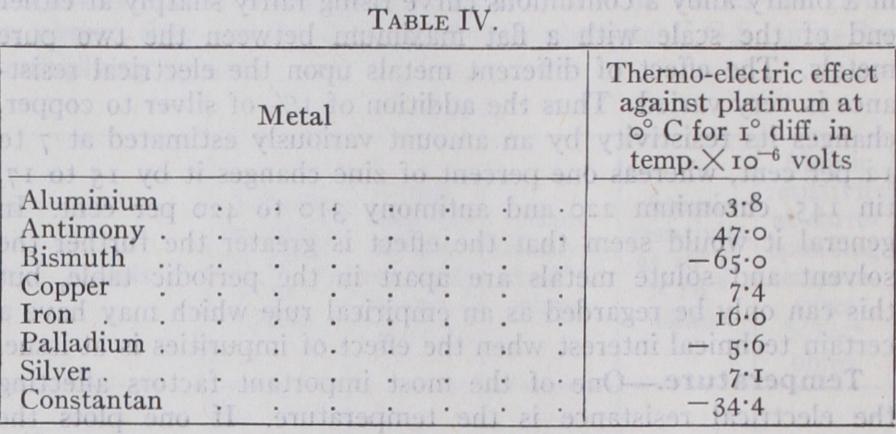

Thermo-electric (or Seebeck) Effect, Peltier Effect and Thomp son Effect.—One cannot consider the electric conductivity of metal without taking into account secondary effects connected with the mechanism by which electricity is transported from one part to another. The best known of these, is the thermo-electric effect, also well known as the Seebeck effect. If two different metals are brought into electrical contact at two points, thus forming a circuit, and the two junctions are kept at different temperatures, a current flows round the circuit. The voltage difference for any given pair of metals, depends solely upon the two temperatures, the current of course being determined by this voltage difference and the resistance of the circuit. At any given temperature the metals may be arranged in a definite order according to the potential difference, which is produced with a given temperature difference between each metal and any one of them arbitrarily chosen as the zero. The potential difference produced by forming a circuit between any two of them is then simply the difference between the voltages pro duced against the standard metal. Table IV. gives a list of the commoner metals and the potential differences produced against platinum for a temperature difference of one degree centigrade at o° C. It is evident that these thermo-electric constants are small, usually less than t o 4 volts per degree. Their magnitude depends upon the temperature, becoming smaller as the absolute zero is ap proached. Small though they are the thermo-electric effect forms the basis of a large class of instruments for measuring tempera ture. It is evident from what has been said, that all that is required is to solder or weld wires of two metals together and measure the voltage difference between the two other ends when the junction is brought to the temperature it is desired to measure.

An inversion of the thermo-electric effect is the Peltier effect. If two dissimilar metals are brought into electrical contact and a current is passed through the junction this is heated or cooled according to the direction of the current, The amount of heating or cooling for a given current at a given temperature depends solely upon the metals used.

The Thompson effect is of somewhat similar character. If a current is passed through a metal, parts of which are at different temperatures, a certain transport of heat takes place, whose amount depends upon the strength of the current. A very im portant property possessed by all good electrical conductors is the faculty of transmitting heat. Thermal conductivity is pos sessed in a greater or less degree by all substances. It is meas ured by the quantity of heat transferred across unit cross-section in unit time for unit temperature gradient. In solids we may distinguish three different types of thermal conductivity. Amor phous solids such as glass possess a conductivity, usually small, which does not vary greatly with temperature. Crystals such as rock salt or rock crystal possess a conductivity roughly inversely proportional to the temperature. At ordinary temperatures it is usually of the same order as the amorphous conductivity of a glass, but at low temperatures clearly it may and does become large. The expression low and high temperatures refers of course to the characteristic temperature of the substance, familiar from the theory of the specific heats.

Electrical conductors possess in addition a thermal conductivity, which would in a non-conductor be considered large and which does not vary greatly with temperature. The mechanism which enables heat to be transported in conductors is certainly closely allied to that which comes into play in electrical conduction. This is shown by the fact that there is a very distinct proportion ality between the electrical and the thermal conductivity of the metals. The so-called Wiedemann-Franz constant is the ratio of thermal to electrical conductivity. As shown by table V. it is approximately constant for a large number of metals, whose conductivities diverge by a factor of no less than 27. It will be noted that there is a steady increase in the constant as the con ductivity decreases. This is in part due to the fact that the metals possess, in addition to electronic conductivity, the ordinary atomic conductivity of every solid. It is clear that this will become more important as the electronic conductivity diminishes. Its amount may be estimated in the case of single crystals, where it is known that the atomic conductivity varies inversely as the temperature and a corrected Wiedemann-Franz constant can be obtained by subtracting the atomic conductivity from the total conductivity and dividing the electronic conductivity, thus obtained by the electrical conductivity. This is found, in the cases examined, to give a result even more constant than that obtained in the table. In the last column of the table may be found the temperature coefficient of the ratio of the conductivities. As will be seen, this is approximately •36 per cent, i.e., the Wiedemann constant appears to be proportional to the absolute temperature. This fact, which is usually regarded as of great importance in any theory of electrical conduction, is of course only another way of stating that the electrical conductivity is roughly inversely proportional to the temperature, whilst the thermal-conductivity is approximately constant. For any theory of electrical conduc tivity, an important factor is the specific heat of the substance. It has been shown that monatomic substance have atomic heats at constant volume, which may be represented with considerable accuracy by one and the same function of the temperature over a characteristic temperature. Measurements have shown that, at any rate at ordinary temperatures and at low temperatures, the metals possess atomic heats confc:ming accurately to this func tion. Reduced to corresponding temperatures, there is no per ceptible difference between the atomic heat curve of a conductor and a simple non-conductor. The conclusion seems inevitable that the mechanism which transmits electricity and heat, and which distinguishes electrical conductors from non-conductors, possesses no appreciable heat capacity of its own. Such are the main characteristics of electrical conductors. It remains to con sider the theories which have been advanced to account for them.

Theories of Electric Conduction in Metals.—Various at tempts have been made to account for the properties of metallic conductors. The first, which for a time was widely accepted, may be described as the electron gas theory (Drude, Riecke, H. A. Lorentz). It was assumed that electrons dissociate from the metal atoms and exist in the interstices between them in much the same state as the atoms of a perfect gas would exist, say, in a heap of shot. According to the classical Kinetic Theory of Gases, the law of equipartition of energy would be fulfilled so that if In is the mass of the electron, k is Boltzmann's constant, and t the absolute temperature : its mean velocity v would be given 2 by the equation At ordinary temperatures, owing to the small mass of the electron, v is very large, of the order of cm/sec. Any velocity which can be superposed by extraneous means, such as an electrical field, is negligible compared to this, Hence one may consider, according to this theory, the electrons to be flying about at high speeds until checked by collision with the atoms, their paths being slightly modified but not materially altered in length by any outside influence. If a field X be applied, the electron will suffer an acceleration X • , e being the charge. If t is the time between one collision and the next, the electron will acquire an extra velocity Xee • t during one free path. If there are is electrons in unit volume the field X will therefore cause a z current to flow, in other words, the specific conductivity 2m 2 will be ne t. In itself, this value is reasonably plausible. If the 2m known figures for e and m are inserted and n is taken of the same order as the number of atoms per cubic centimetre t is of the order 1015 which corresponds to a free path of cm., the order of distance between the atoms. Without supplementary hypotheses however, it is not clear why the conductivity should vary inversely as the absolute temperature.

The thermal conductivity, according to this theory may, of course, be attributed to the same mechanism which causes a gas to transmit heat. It is merely the diffusion of the hotter and therefore swifter particles, into the more slowly moving ones and the transfer of heat from one group to the other. If A T is the temperature gradient, the amount of heat transferred accord s ing to the ordinary kinetic theory is nv t • AT. Hence the con 2 ductivity is k t, 3k course representing the heat capacity of 2 2 the electron. This expression again gives rise to reasonable values.

The real triumph of the theory is manifest when the Wiede mann-Franz constant, the ratio of thermal to electric conductivity is formed. Inserting the two expressions, it is clear that the quantities n and t, i.e., the number of electrons per cubic centi metre and the time between collisions (those quantities which might well be expected to vary from metal to metal), cancel out, 2 for the ratio of thermal to electrical conductivity 3 T.

Hence the theory explains why the ratio of thermal to electrical conductivity is the same in all conductors and also predicts that it should be proportional to the absolute temperature, as was found empirically. Not only does it give a qualitative explana tion, but it gives a very fair approximation to the absolute value, if the known values of k and e are inserted.

The theory of course gives a qualitative explanation of the effect of a magnetic field, since this would cause the deflection of moving electrical particles, though the inverse magnetic effects require supplementary hypotheses ; it also explains qualitatively the thermoelectrical, Peltier and Thompson effects, since the electron gases in two different metals would not in general have equal pressures, and, as in the case of osmotic cells (see Solution), one would always have a balance between the tendency to diffuse under the influence of thermal agitation and the potential differ ences set up as soon as movement of the electric charges take place.

The difficulty which proved fatal to this theory, is that it in volves the assumption that the electrons have the atomic heat of a monatomic gas. Without this, one cannot obtain the Wiede mann-Franz constant, but if one makes this assumption then the metals should possess atomic heats considerably greater than the non-metals. Of this there is no trace. One cannot escape the dilemma by assuming that only a very small fraction of the atoms dissociate, for in this case thermodynamics shows that the number of electrons would vary rapidly with temperature becoming neg ligible at low temperatures just where the conductivity is greatest. Thus this theory, great as was the advance which it marked upon the previous attempts to explain the nature of metallic conduction, has had to be abandoned.

Numerous other theories have been put forward to account for the phenomena whilst avoiding this difficulty. One of the first (J. J. Thompson) endeavoured to resuscitate something akin to the Grotthus chain theory of electrolytes. The atoms were con sidered as dipoles and electric conduction was attributed to the transfer of electrons from one atom to the next. Under the in fluence of the field the dipoles would tend to arrange themselves, and the probability of an electron being pulled out of the negative part of one dipole into the positive part of the next, would be increased. If the dipoles are distributed at random, there will be no tendency for the electrons to flow in any definite direction, it is only the polarisation on this theory which gives rise to the current. If one supposes that the kinetic energy of the electron in the doublet is proportional to the kinetic energy of the doublet, then of course a transfer of particles will involve the transfer of energy from hot to cold parts of the metal and give rise to heat conduction. This theory is incompatible with modern views and has scarcely more than historical interest. The mechanism of dissociation, the assumption that the kinetic energy of the electron equals that of the atom and values which emerge, if the figures are inserted in the formula, disprove its validity. It has been mentioned, chiefly because it may be regarded as the precursor of a theory which has been put forward much more recently by Bridgman. In this the electric current is attributed in the main to the flow of electrons inside the atoms, not to the motion of electrons between them. The hindrances to the free flow of electrons are found according to this theory, not in the atoms themselves, but in the gaps between the atoms. The theory was concerned chiefly to explain the increase in conduc tivity, usually observed under hydrostatic pressure. This, it need scarcely be said, is quite simple since pressure will tend to close the gaps between the atoms. The effect of temperature which causes expansion of the metal and raises the amplitude of the atomic vibrations is to increase the number of gaps and the re sistance. Heat conduction is explained as partly electric and partly atomic though the share attributed to the atoms is far larger than one would normally expect. It seems probable that the somewhat crude assumptions which underlie it, and the additions which have become necessary in order to explain even such a funda mental quality as thermal conductivity, will militate against the acceptance of this hypothesis.

Various theories (Lindemann, Wien) were based upon the as sumption that the free path of the electrons depends upon the amplitude of oscillation of the atoms. This explains at once why the resistance is proportional to the energy content of the solid, since pressure augments the forces between the atoms the frequency is increased and for a given energy, the amplitude diminished. From this point of view it is to be expected that an increase in pressure would lead to a decrease in resistance, since a decreased amplitude means an increased free path. Scarcely one of these theories progressed beyond the first tentative be ginning, and none of them appear likely to survive. A theory of a totally different kind, put forward by Lindemann, en deavoured to reconcile the great heat conductivity of metals with the negligible heat capacity of the electron by treating these as forming a space-lattice, interleaved between the atomic lattice. As has been pointed out, a crystal at low temperatures conducts heat comparatively well, even though its atomic heat may be negligible. This fact, which had been plausibly explained by Debye, appears to suggest a simple mechanism for the transfer of heat in metals.

Electrons repel one another so strongly that the idea of an electron gas is almost a contradiction in terms, unless one attrib utes enormous velocities to the particles. At ordinary tempera tures the equipartition energy would only suffice to make the particles quiver, if each atom in a solid had dissociated an elec tron. Under the influence of an electric field the electron space lattice would move continuously through the atomic space-lattice, provided a source of the electrons were connected to one end of the conductor, and if the electrons were able to flow out at the other, i.e., if the circuit were closed. In pure metals at extremely low temperature, it seems possible that the electron space-lattice might move almost unimpeded through the atomic space-lattice; with increasing temperature the amplitude of oscillation of the atoms increases and obstacles would be interposed to the space lattice drift. In an impure metal a constant resistance would be superposed upon the resistance due to the thermal agitation, on account of the irregularities produced in the original atomic space-lattice by the foreign atoms embedded in it. The forces between the electrons, as was pointed out, would be of the same order as the forces between the atoms. Since the electron has a very small mass the proper frequency, and therefore the char acteristic temperature of the electronic space-lattice would be extremely high, of the order of one hundred thousand degrees. Thus the heat capacity of the electrons would be negligible though, since they would form a crystal, they could conduct heat. All the minor effects can of course be explained on similar lines to those current in the theory which treats the electrons as form ing a perfect gas. The main advantage which this theory pos sesses, besides avoiding the contradiction involved in attributing to a perfect gas, heat conductivity without heat capacity, is that it gives a plausible reason for the large increase of resistance, which may be caused by the admixture of a foreign element and also that it accounts for the fact that metal crystals may have different conductivities along different axes.

The most recent theory (Sommerfeld) treats the electrons as a completely degraded gas. It is difficult to go into this in any detail without a considerable digression upon wave mechanics and the modifications of statistical mechanics, imposed by what is usually called the quantum theory. It has been suggested by Pauli that no two electrons in an atom can have the same four quantum numbers. This simple rule explains the existence of the periodic system of the elements. The same rule was applied by Fermi to a gas. This leads at high temperatures to the ordinary laws. At low temperatures however, the gas would deviate con siderably from the state predicted by the classical theory. At the absolute zero it would still exert a pressure and possess energy, for clearly since only one atom can have the four quantum numbers, all the other atoms must contain some energy. If one applies the formulae of this theory to the electrons in a metal, one finds a considerable measure of agreement with experimental fact. As in the classical electron gas theory, the number of elec trons in unit volume and the time between collisions enters in the same way into the formulae for the electrical and thermal conductivities. Hence the Wiedemann-Franz constant emerges, and what is more, its absolute value agrees somewhat more closely with experiment than it does according to the classical theory. The heat capacity of the electrons is negligible, for their mass is so small that it only amounts to a fraction of one per cent of the heat capacity of the atoms. The exact meaning of the free path on this theory, is as yet perhaps not quite clear and special assumptions have to be made about it in order to explain the variation of a resistance with temperature. No obvious explana tion is given for the large effect of impurities, nor does it seem easy on this theory, to account for a difference in conductivity along the different axes of a crystal. On the other hand, the fact that it is possible to obtain the Wiedemann-Franz constant with out having to assume a large heat capacity, marks a notable advance.

Non-metallic Conductors.—Little accurate information is available about non-metallic conductors. Many of them exhibit departures from Ohm's Law and some of them are not even inde pendent of the time in their electrical characteristics. Numerous specimens of various substances have been examined with con siderable care, but the values found depend so much upon the treatment and form of the specimen, that no useful purpose would be served by a detailed description of the results. Thus for instance, carbon, one of the most carefully investigated sub stances, displays values of the conductivity according to its form, varying by as much as a factor three and if the allotropic modi fication, graphite is included, by as much as twenty to one. In general non-metallic conductors have a very much higher resist ance than metallic conductors, carbon for instance, having a re sistance two thousand times that of copper at ordinary tempera tures. All of them have a negative temperature coefficient, i.e., the resistance decreases with rise of temperature, unlike metals whose resistance, except for some curious alloys, invariably in creases as the temperature is raised. At sufficiently high tempera tures, there is in some cases a change in the sign of the tem perature coefficient, but not sufficient evidence is available to allow any generalization from this. Apart from carbon in its various forms, some of the oxides and sulphides of the metallic elements, are the non-metallic conductors which have been most closely studied. Table VI. gives the resistance found in the case of copper and silver sulphide at various temperatures. It will be seen that the increase in conductivity is extremely large for a comparatively small change of temperature, of the same order as the change in viscosity of many substances for an equivalent change. It seems likely that it is some such effect which accounts for the temperature coefficient.

Many of these substances exhibit a very remarkable property, in that the transition of electricity from one of them to a metallic conductor placed in contact, proceeds very much more easily in one direction than the other; in some cases the resistance is more than a thousand times greater in the one than the opposite sense. It is this property which is made use of in the rectifying devices used either for high frequency currents, as in the crystal detector, or for low frequency rectification on a small scale.

One other non-metallic conductor has been the subject of the most minute examination, namely selenium. In certain modifica tions this substance exhibits a very curious phenomenon ; its resistance is changed by illumination. The conductivity in suit able circumstances may be increased by 6% by illumination of one metre candle, the effect within wide limits being proportional to the square root of the illumination.

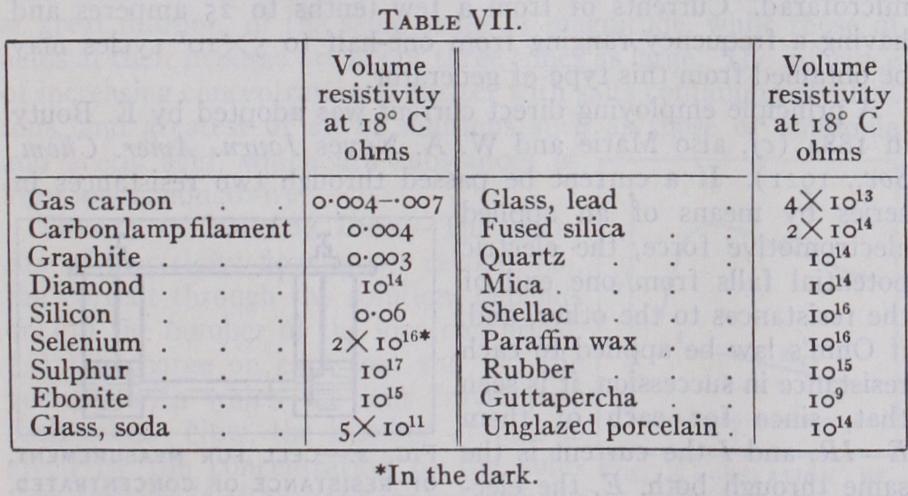

Many attempts have been made to utilize this property for the measurement of light and for the production of electric currents corresponding to incident light for various purposes. Unfortu nately the very large temperature coefficient, the variation of its resistance with humidity, and especially the slow response of sele nium to weak illumination, usually stands in the way of complete successes. The effect is probably due to some allotropic modifica tion produced in the material by light and it is not surprising that insulating cables and the like. It is evident that such substances are not those likely to be chosen if it is desired to discover the mechanism of dielectric conduction. In general, as in the case of many of the non-metallic conductors, it is of dubious validity to employ the concept of electric resistance at all, as this is often in dielectrics, a function of the time as well as of the voltage ap plied. The resistance at room temperature for a few of the com moner insulators are given in the Table VII. In general the con ductivity increases very rapidly with rising temperature, probably for the same reason that has been suggested in the case of non metals. The accuracy of the measurements is vitiated in many cases by the presence of moisture which is apt to form in a thin conducting layer over parts of the surface. Thus in many cases, it is more important to use an insulator which can be thoroughly dried, than to seek one of a high specific resistance. At a suffici ently high voltage all these insulators break down and a spark oc curs. This so-called dielectric strength is a matter of great techni cal importance, but it also depends to such a large extent upon the peculiar circumstances of the experiment, that only two typical cases, mica and crystal glass, are given as examples.

Some extremely valuable work, from a scientific point of view, has been carried out in the last few years by Pohl upon the transfer of electricity in certain dielectrics. He found that many dielectrics more especially sodium chloride exhibited a form of conductivity under the influence of light. This he could show was due to the production of photo-electric electrons whose dis placements formed a current. Though this can scarcely be regarded as conductivity in the ordinary sense, it does represent one of the first cases in which the movement of electricity through a dielectric has been treated upon a quantitative basis.