Cosmic Radiation

COSMIC RADIATION Penetrating Radiations.—As early as 1903, several investi gators, among whom were J. McLennan, E. F. Burton (5903), E. Rutherford, and H. L. Cooke (1903), made investigations of the residual ionization in closed vessels with and without absorb ing screens of lead. Under ordinary conditions over land, about 10 ions are produced per cu.cm. per second in a closed unshielded metal vessel freed as far as possible from radioactive contamina tion. That a portion of this ionization is due to the earth itself and to radioactive emanations in the atmosphere is borne out by the fact that, over the ocean, the residual ionization falls to about 4 ions per cu.cm. per second. Moreover, measurements in a vessel of ice made over Lake Ontario by J. McLennan and his collaborators gave a value as low as 2.6 ions per cu.cm. per second. In 1911, V. F. Hess in Austria and W. Kolhorster (in 1913-14) in Germany published results of balloon ascents, and the net result of this work was the conclusion that the residual ionization dimin ished with altitude up to an altitude of about i,000m. and then increased with further increase of altitude until at 9,000m. it was about seven times as great as at the earth's surface. The diminu tion up to i,000m. was attributed to the diminution of the gamma-ray radiation from the earth.

In 1921 and 1922, R. A. Millikan and I. S. Bowen sent pilot balloons fitted with electroscope measuring systems up to altitudes of ten miles. One of these balloons survived accidents sufficiently to permit an interpretation of its records, and from this Millikan and Bowen concluded that the absorption coefficient of the radia tion was much less than that found by Kolhorster. Happily the divergence between the values of different observers for the ab sorption coefficient of the more penetrating part of the radiation is not so great as to prevent agreement on the conclusion that it is much greater than that for ordinary gamma-rays, so that it is possible by suitable shielding of the apparatus to diminish to relative insignificance the true gamma-ray part and so disentangle it from the more penetrating part. In 1923 W. Kolhorster made absorption measurements of the radiation on Alpine glaciers, while R. A. Millikan and R. M. Otis made absorption measure ments on lead at the summit of Pike's Peak. Kolhorster's data gave an absorption coefficient of 0.25 per metre of water. On the other hand, R. A. Millikan and R. M. Otis (1926) concluded that if there existed any rays of cosmic origin they must be more penetrating than Kolhorster found, or the intensity at sea-level must be less than corresponding to the value of 2 ions per cu.cm. per second which he regarded as the most probable value.

In 1925, R. A. Millikan and G. H. Cameron, by sinking appa ratus to various depths in snow-fed lakes at high altitudes arrived at the conclusion that there existed a radiation of cosmic origin such as would produce 5.4 ions per cu.cm. per second in the ion ization chamber at sea-level. Moreover, they concluded that this radiation was of a non-homogeneous type, varying in absorption coefficient from 0.18 to 0.3 per metre of water. Still further measurement experiments have led them to extend the range of absorption coefficient from o• 1 to 0.25; and in their most recent publication (June 1928) they have analyzed the radiation into three parts corresponding to the coefficients of absorption, per metre of water, 0.35, 0.08, 0.04. On the other hand, G. Hoffmann (1927), on the basis of Kolhorster's results, found 0.29 ions. per cu.cm. for the ionization at sea-level.

Measurements of the residuary ionization as a function of the pressure in the ionization chamber lead to the conclusion that the increase of ionization per atmosphere increase diminishes with pressure increase. Such measurements are of interest because the increase of ionization per atmospheric increase at high pressures is independent of the effects of soft radiation emitted from the walls of the vessel as a result of radioactive contamination or even as a result of the action of the primary radiation. While the increase in ionization per atmosphere is not the same thing as the ionization produced in a vessel at one atmosphere, it is closely related to it ; and it appears (W. F. G. Swann, 1922), on the basis of plausible assumptions, that the least value of the increase of ionization per atmosphere for the whole ionization pressure curve is greater than, or at least equal to, the ionization which would be produced by the direct and secondary actions of the penetrating radiation in the gas itself. Experiments on the variation of residual ionization with pressure have been made by W. Wilson (19°9), by J. C. McLennan and E. F. Buxton (1903), and in more recent times (192o) by W. F. G. Swann and his collaborators, K. Melvin Downey, H. F. Fruth and J. W. Broxon. In 1926 W. F. G. Swann made measurements at the summit of Pike's Peak (I 4,1 oof t.) , at Colorado Springs (6,000f t. ) and at New Haven (sea-level). The increase of ions per cu.cm. per atmosphere was measured in a vessel of iron 'in. thick sur rounded by tin. of lead, and, at the highest pressures, was 0.23 ions per cu.cm. per atmosphere at sea-level. As regards the absorption coefficient, observers previous to Millikan have used the expression for the intensity/ in terms of the intensity outside of the region of atmospheric absorption. Here µ is the absorption coefficient, and H the altitude of the top of the atmosphere above the point if the atmosphere were rendered homogeneous and corresponding in density to the density at sea level. The above formula does not take into account the fact that the radiation comes in from all directions. A formula taking co this into account is and such a formula was used x by Millikan and Cameron. These two formulae give decidedly different values of for the same experimental data, a fact which must be taken into account in comparing the actual content of the results of different observers. Thus, when reduced to a value corresponding to a unit of absorption of one metre of water, Swann's results given by the first formula are, (Pike's Peak– Colorado Springs) =0.39o; µ (Colorado Springs–New Haven) = 0.17 2. The corresponding data as calculated by the more com plicated and more appropriate formula are 0. I 20 and 0.305. These latter values are comparable with those found by Millikan. Origin of the Cosmic Radiation.—If the results of the low coefficient of absorption be accepted, then that origin of the cosmic rays as ordinary gamma radiation from radioactive material in the higher regions of the atmosphere, or elsewhere, becomes ruled out. The most natural assumption as to the nature of the rays is to regard them as gamma-rays of a very high penetration produced by encounters between the nuclei of atoms and electrons of very high energy. Rays having an absorption coefficient of o• 18 per metre of water would be expected to have a wave-length of and to produce them would require an electronic energy corresponding to a fall of the elec tronic charge through about 33X I volts. It has been suggested by W. F. G. Swann (1919) that the origin of the penetrating radiation may be found in the X-rays produced by the electrons from the sun which Birkeland supposed responsible for the aurora. Birkeland's calculations assign to these electrons a velocity of only 45m. per second less than the velocity of light. Such elec trons would have energies corresponding to volts which would be more than is required for the purpose, so that the softer rays which would be too soft to correspond to the aurora except in very high altitudes would, as far as energy considerations are concerned, serve for the cosmic rays.

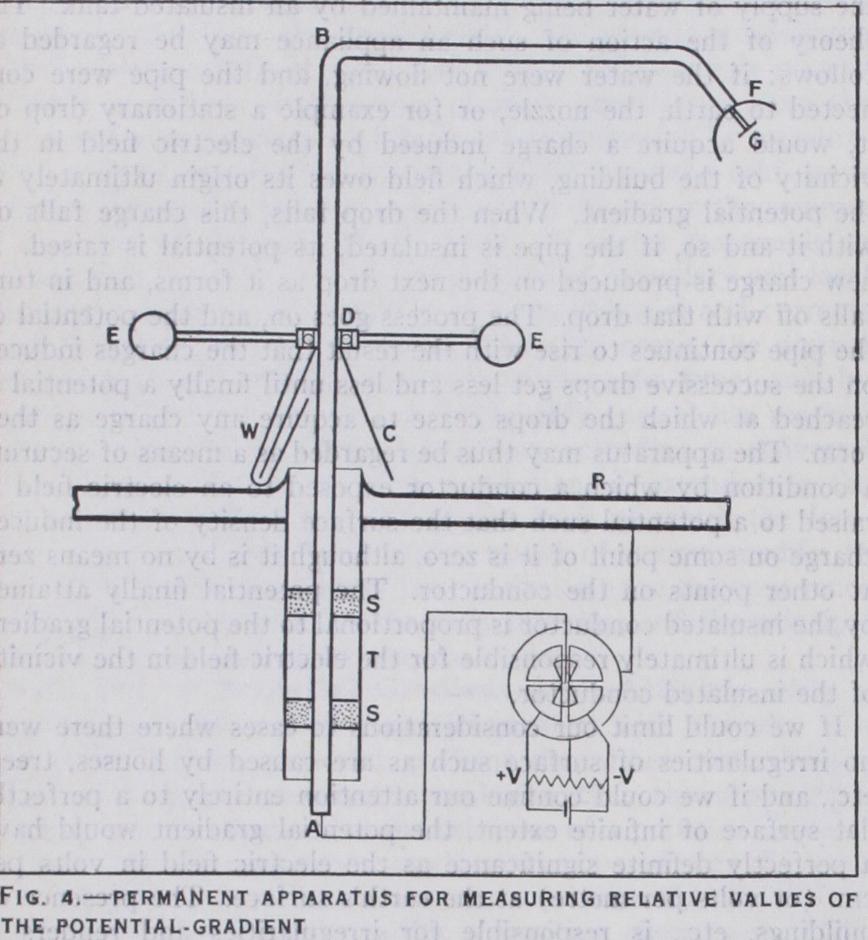

In weighing such a hypothesis in the light of experiments con cerned with the direction of the radiation in relation to the sun, one must remember that the magnetic field of the earth prevents anything like a rectilinear approach of the electrons towards the earth. Even electrons of velocity corresponding to I,000X I volts could not approach the earth in the equatorial plane nearer than eight times the earth's radius before being turned back into space, and many electronic orbits circle the earth several times. C. T. R. Wilson (1925) has suggested that electrons with many millions of volts velocity may be produced in lightning flashes. On the other hand, Millikan inclines to the view that the cosmic rays owe their existence to neither the sun nor lightning flashes, but that they represent energy radiated during the actual creation of such atoms as helium, oxygen and silicon out of electrons and protons in interstellar space. (See RADIATION.) Potential Gradient.—One type of device for measuring rela tive values of the potential gradient is illustrated by the water dropper, which comprises primarily an insulated pipe connected at one end to a quadrant electrometer or to an electroscope, and with the other end projecting through a window and exposed to the earth's electric field. To this exterior end is fastened a nozzle through which water flows in a fine stream, breaking into drops, the supply of water being maintained by an insulated tank. The theory of the action of such an appliance may be regarded as follows: if the water were not flowing, and the pipe were con nected to earth, the nozzle, or for example a stationary drop on it, would acquire a charge induced by the electric field in the vicinity of the building, which field owes its origin ultimately to the potential gradient. When the drop falls, this charge falls off with it and so, if the pipe is insulated, its potential is raised. A new charge is produced on the next drop as it forms, and in turn falls off with that drop. The process goes on, and the potential of the pipe continues to rise with the result that the charges induced on the successive drops get less and less until finally a potential is reached at which the drops cease to acquire any charge as they form. The apparatus may thus be regarded as a means of securing a condition by which a conductor exposed to an electric field is raised to a potential such that the surface density of the induced charge on some point of it is zero, although it is by no means zero at other points on the conductor. The potential finally attained by the insulated conductor is proportional to the potential gradient which is ultimately responsible for the electric field in the vicinity of the insulated conductor.

If we could limit our considerations to cases where there were no irregularities of surface such as are caused by houses, trees, etc., and if we could confine our attention entirely to a perfectly flat surface of infinite extent, the potential gradient would have a perfectly definite significance as the electric field in volts per cm. (or volts per metre) at the earth's surface. The presence of buildings, etc., is responsible for irregularities and renders it desirable that we crystallize in our minds a reasonably exact mean ing to the potential gradient under such conditions.

Let us picture a problem in which the potential is specified as zero over an irregular contour of sensibly infinite extent, such as the surface of the earth with its buildings and irregularities, and in which the electric field is specified as vertical, constant and equal to X over some plane at an altitude large compared with the dimensions of the irregularities considered. Then, the equation of Laplace (AV' = o) , which governs the variation of the field in the space considered, has a unique solution for the problem assigned. The surface density a, which is determined at the surface of a conductor by the relation field = 4rra, becoming also uniquely determined. We may define the potential gradient corresponding to an undisturbed earth's surface at the place con sidered as the value of X necessary to secure, in a problem of the above kind, the distribution of surface density actually existing over the surface of the earth, houses, trees, etc. ; or if one so prefers, the value of X necessary to ensure the field intensities actually measured at the various places.

Suppose that now, in the above problem, we should include an insulated conductor. In general it would have induced charges on it. If, for example, it were a vertical rod with zero total charge it would have a negative charge at the top end and a positive charge at the bottom end. Whatever the body might be, it would always be possible to assign to it a potential so high in relation to the arbitrary zero of the earth that the surface density on any specified point P of it was positive, or a potential so low that the surface density at P was negative, and consequently it would be possible to assign to it one, and, in general, only one potential V which would make the surface density at P zero. The potential V necessary to assign to the conductor to secure zero surface density at P is obviously proportional to X, since multiplying the potential at each point by a constant n secures a new solution uniquely determined throughout all space, and corresponding therefore to zero field at P, to a field i X at infinity, and to a potential 77 V for the insulated conductor.

Another method which has been used to secure a condition of zero surface density at some point of an insulated conductor is to attach there a small plate, called a collector, covered with a radioactive preparation which imparts conductivity to the air in the vicinity of the point and enables the plate to acquire a charge from its surroundings until the field at its surface and so the surface density there, is zero. If there were two collectors on different parts of the insulated system, each would make an effort to reduce to zero the surface density in its vicinity, but a situation with the surface density zero in two places could not, in general, be realized by any potential which the insulated system could acquire. A compromise would be reached depending upon the relative conductivities imparted to the air in the vicinities of the two collectors. A somewhat similar situation arises with a single collector when the range of ionization of its rays is large, since then a variable conductivity of the air is to be found over a relatively large portion of the collector support. Under such conditions the final potential attained by the insulated system depends upon the distribution of air conductivity about the con ductor and so depends upon the wind velocity. In order to avoid these complications it is customary to use a radioactive prepara tion emitting only alpha-rays whose range in air is confined to a few centimetres. Polonium and ionium are frequently used. Oc casionally a flame takes the place of the collector for the pur pose of rendering the air conducting over a restricted region.

An apparatus suitable for continuous use is shown in fig. 4.

The sulphur plugs S, fastened on the tube T which is fixed into the roof R of the observation house serve to insulate the rod AB and its various attachments C, D, E, F, W, and the radioactive plate G. The cap F serves to protect the radioactive plate, and the cone C, the hole in the roof, from rain. The wire W is mounted on a ball-bearing D and is kept in rotation by the wind vanes E. In this manner spider threads are prevented from forming in such a way as to connect the insulated system to ground. The insulated system is connected to the needle of a quadrant electrometer whose quadrants are kept at such poten tials -}-V and --V in relation to the case as will ensure a con venient sensitivity. By means of a beam of light reflected from a mirror on the electrometer needle to a revolving drum covered with photographic paper, the motion of the needle is recorded.

In order to obtain the absolute value of the potential gradient, it is necessary to secure a horizontal surface of large extent. One may then suspend a horizontal wire by two insulators from two vertical posts at a distance of Tom. or possibly more. the wire being one or two meters above the ground. A collector is attached to the centre of the wire and the insulated system of an electro scope is attached to one end, the case of the electroscope being earthed. Under these conditions, when the equilibrium potential is attained and the collector carries no surface density of charge, the wire also carries no surface density of charge, since it is at the altitude of the collector, and consequently the potential of the wire is simply that which the horizontal plane containing it would have in its absence. The potential recorded by the electroscope divided by the altitude of the wire gives the absolute value of the potential gradient, and the apparatus serves to determine for any other apparatus situated at not too great a distance, a reduction factor by which the readings of the second apparatus may be reduced to absolute value.

Methods other than the water dropper and the radioactive collector have been devised for obtaining relative values of potential gradient. These utilize, as a rule, the fact that the potential gradient induces a charge on an earthed conductor. In C. T. R. Wilson's universal electrometer, a disc connected to an electroscope is exposed to the atmosphere and, together with the electroscope case, is earthed. Under these conditions the electro scope shows no deflection. A cover is then placed over the disc. The charge on the disc now distributes itself throughout the electroscope and the leaves diverge to a potential which is pro portional to the potential gradient. In actual use the deflection of the leaves is compensated by means of a variable condenser with one armature attached to the insulated system, the other being kept at a known potential V. By altering the capacity of this condenser it is possible to throw a charge on to the electro scope from the condenser and so compensate the deflection pro duced by other causes. This charge is VC ; where C is the change of capacity of the condenser (or more precisely, the change of coefficient of induction between the insulated system and the outer member of the condenser), and the quantity VC is thus pro portional to the potential gradient.

Measurements of Conductivity and Ionic Density.— Measurements of conductivity depend upon a theorem, which is fundamental in many calculations in atmospheric electricity, to the effect that if a body with a charge Q is exposed to a current of air of sufficient velocity, the rate of loss of charge is given by the expression where n, v and X' refer to the ions of sign opposite to that on the charged body, n is the ionic density, e the electronic charge, and v the mobility.

The foregoing theorem was first developed by E. Riecke (1903) for the case of charged sphere, and it was applied to the case of infinite concentric cylinders by H. Gerdien (1905), in both cases the air flow being supposed to occur in parallel lines with constant velocity. It was developed by W. F. G. Swann (1914) for a general air motion of arbitrary type, and for a body of any shape, as follows.

Confining our attention for the moment to ions of one particu lar sign, if N is the total number of ions within any volume at some instant, then the rate of increase of N with time is given by where w„ and are respectively the components of the air velocity and of the electric field in the direction of the outwardly drawn normal from the surface, n is the ionic density of the ions, and v the mobility, regarded as negative if the ions are negative. Since the rate of increase of air within any volume is zero If n is constant over the surface where q is the charge contained within the boundary of the volume.

Now in all calculations concerned with the theory of atmospheric electric instruments, and having to do with the motion of ions to charged conductors, it has been customary to neglect the field caused by any space density of electricity in the space around the conductor, compared with that due to the charge on the con ductor itself. This amounts to neglecting q in (3) when the surface does not surround the conductor, and (3) then leads to We can readily ascertain the limitations of the conclusion on which the foregoing result rests, viz., the conclusion that n is constant over the boundary of the volume considered. The stream lines of the ions are completely determined by the velocity of the air and by the electric field. Let us consider any tube of stream lines of ions and let the volume referred to above be the volume at P enclosed by the walls of the stream tube and two surfaces drawn across it at R and S, fig. 5A. Then, if the density is the same at R and S before the application of the field, dN/dt will be zero immediately after the application of the field, so that the ionic density within our volume will not change in the time dt. The same argument applies to all the elements of volume into which the tube may be divided, and if this tube extends back to infinity it continues to apply at P for each successive element of time dt. In other words, the ionic density remains constant with the time all along the tube. In general, the ions increase in speed in going from a place of small to a place of large field, but any thinning out of the density which might at first sight be supposed to occur as a consequence is compensated by a drawing together of the stream line in regions where the field is high.

Suppose that now as we produce the stream lines of the ions back, we encounter an obstacle D, as in fig. 5B. Then while it is still true that dN/dt is zero at the initial instant at P, it will not be zero, initially, for the element of volume adjacent to the surface of D. The part of the stream tube in the immediate vicinity of D will have all its ions removed and the boundary between the part of the tube where the ionic density has its original amount and the part where it is zero will move down the tube until it eventually reaches the boundary of P, and at that instant the ionic density in the element at P will change. In fact, neglecting re-formation of ions and diffusion, any stream tube which, on projection back, encounters an obstacle will become completely denuded of ions. The simple theory which neglects diffusion and the field due to space density of charge in the air permits only two possible situations in the steady state. Considering the ions of any one sign, either their density at a point remains constant with time and equal to the value undis turbed by the field, or it falls to zero. The sorts of situations which arise are represented in fig.

6. Suppose the sphere is posi tively charged, and that the air current is from right to left.

Then, in general, the space around the sphere divides itself into two portions separated by the heavy line, fig. 6A. In the region outside of this space, the paths of the positive ions are of the general nature shown by the arrows, and the density is con stant and equal to its value at infinity. Within the heavy lines the positive ionic density is zero, and the paths by which the ions have been cleared out are dotted. On the other hand, fig. 6B shows the general paths of the negative ions. Here again the density is constant, but the stream lines divide themselves into two groups, those which go to the sphere and those which escape it.

Returning to our conductor of general shape, let us suppose it to have a positive charge, Q. Then, provided that all the stream lines of the negative ions flowing to it can be produced back to infinity without encountering obstacles, equation (2) may be ap plied to the surface immediately surrounding the conductor and n may be taken outside the integral sign and allotted its value at infinity. Equation (3) follows, but the quantity q now refers to the charge Q on the conductor, so that multiplying throughout by e, the charge on an ion, dNe/dt becomes dQ/dt, and dQ = — 47rQnev = — 47rQ X' (4) dt As a matter of fact, these results, which have been proved for the conductor as a whole, may be extended to any part of it with Q referring simply to the charge on that part, provided always that the stream lines from the part when produced back go to infinity without encountering obstacles. In case obstacles are encountered, the absolute value of dQ/dt is less than that calculated above.

The foregoing principles have been utilized in an apparatus designed by H. Gerdien (19o5), in which air is drawn by a fan between two concentric cylinders, the inside member of which is insulated, charged and connected to an electroscope. The smaller the potential of the central cylin der, or the higher the velocity of flow, the narrower the cylin drical stream of air from which the central cylinder draws ions. Provided the outer cylinder is wide enough to accommodate this cylindrical stream, so that the ionic stream lines can be traced back from the central cylinder and out through the opening of the outer cylinder without encountering the wall of the latter, we may apply (4). If is the capacity of the part of the insulated system exposed to the air current, C, the capacity of the whole insulated system, and V its potential, (4) gives X' = C , log Vl (6) which gives X' in terms of the initial and final potentials, and the time to pass between them.

If, in the Gerdien conductivity apparatus, the potential is raised to such a point that the cylindrical boundary of the ionic stream lines which go to the central conductor swells out so as to touch the outer cylinder, then for this and for all higher potentials the "saturation current" obtainable with the given rate of flow of air will be obtained; and above this potential the rate of charging of the central conductor will be independent of the potential difference between the cylinders. It will, in fact, be given by --dQ = Pine dt where W is the number of cu.cm. of air passing through the system per second. If C is the capacity of the entire insulated system = dt which serves to determine n in terms of measurable quantities.

If the conductivity, say for negative ions, X_ = n _ev _ is known, and if also the value of n_ is known, the mobility v_ may of course be obtained by division.

It is customary to use for the determination of the ionic density a pair of cylinders of much smaller diameter than those used for the conductivity measurements, so that a saturation current may be the more readily secured. In this form the apparatus is usually known as Ebert's ion counter. In the modern form, the axis of the concentric cylinders is vertical, and, in spite of the fact that the upper end of the cylinders where the ions enter is shielded by a cap, the negative charge induced by the potential gradient on the region of entry produces serious errors in the case of the measurements for negative ions, although no error exists for positive ions.

Another method, that of Schering (1908), which has been used for measuring the unipolar conductivities, involves the use of a long wire stretched parallel to the ground, and surrounded by a wide cylindrical wire netting connected to earth. The wire is charged and connected to an electrometer. It proceeds to lose its charge according to the law expressed by (4), provided that a breeze of air blows through the netting, and the conductivity may be calculated, as in the Gerdien apparatus, from a knowledge of the ratio of the capacity of the wire (surrounded by its netting) to the whole capacity of the insulated system, of the potential, and of the rate of fall of potential. This apparatus, and also the aspiration apparatus, has been adapted to the purposes of con tinuous registration of conductivity. Another method of measur ing atmospheric conductivity is afforded by C. T. R. Wilson's portable electrometer. If the plate of that instrument is earthed and exposed to the atmosphere it acquires a negative charge. If it is now insulated, it starts to lose that charge at a rate deter mined by (4). By means of the compensator the electroscope may be kept undeflected, and the value of dQ/dt may be deduced from the rate of change of the compensator reading. The total value of Q at the initial instant may be obtained by shielding the test plate with the cap, and adjusting the compensator to reduce to zero the deflection caused thereby, in the manner already de scribed in connection with the use of the instrument for measure ment of the potential gradient. The data thus obtained serve to yield X' by the aid of (4).

The air-earth conduction current density may be obtained by multiplying X++X_ by the potential gradient. If it should be true that the emission of negative ions from the ground were insuf ficient to contribute appreciably to the air-earth current density then the latter could be obtained directly by compensating the loss of charge per second from an insulated plate in the manner adopted in C. T. R. Wilson's electrometer, but with the apparatus arranged so that the test plate was level with the ground. This method has occasionally been utilized for measurements of the air-earth current density. The relation of the quantity so meas ured to that obtained by multiplying by the potential gradient is rather a complicated one, involving as it does the emission of ions from the pores of the soil, and the convectional effects of the air motion.

Measurement of the Radium Emanation Content of the Air.—J. Satterly (191o) and others have made absolute determination of the emanation content of the atmosphere by passing air through a liquid air-cooled tube which condensed the emanation and thus permitted its subsequent determination. Coconut charcoal has also been used to retain the emanation.

In an apparatus used on the American yacht "Carnegie," air was drawn at a measured rate and for a fixed time between two concentric cylinders with a potential difference between them of such sign and amount as to cause all the radium A, B and C to deposit on the central cylinder, or rather on a copper foil wrapped around it. The foil was reversed at the end of the assigned time and caused to line another vessel, its outside being now turned towards the inside. This vessel was provided with an insulated rod which was connected to an electroscope, so that by placing a po tential difference between the vessel and the rod the saturation current due to the ions formed by the radioactive material could be measured and plotted against the time. From the data thus obtained it was possible to work back and deduce the radium emanation content of the atmosphere.

Measurement of the Penetrating Radiation.—Most meas urements of the penetrating radiation have been made by a method illustrated by the following. A thin metal vessel of about 3o litres capacity is provided with a central rod insulated from it and con nected to one quadrant of an electrometer, the other quadrant being connected to the electrometer case. A potential of ioo volts between the wall of the vessel and the rod serves to main tain a saturation current to the electrometer, the current being determined by the rate of production of ions in the vessel. This current may be deduced from measurements of the rate of de flection of the electrometer, or preferably by compensating that deflection by a variable potential applied to the outer member of a subsidiary condenser whose inner member is connected to the rod associated with the ionization vessel. Several important pre cautions are necessary to secure a reliable result.

The rate of production of ions per cu.cm. resulting from such measurements as the above depends on more than one cause, as already explained.