Earliest Times to Muslim Conquest

EARLIEST TIMES TO MUSLIM CONQUEST The Prehistoric Age.—Tradition, mythology and later cus toms make it possible to recover a scrap of the political history of prehistoric Egypt. Menes, the founder of the 1st Dynasty, united the two kingdoms of Upper and Lower Egypt. In the pre historic period, therefore, these two realms were separate. The capital of Upper Egypt was Nekheb, now represented by the ruins of El Kab, with the royal residence across the river at Nekhen (Hieraconpolis) ; that of Lower Egypt was at Buto in the marshes, with the royal residence in the quarter called Pe. Nek hebi, goddess of El Kab, represented the Upper or Southern Kingdom, which was also under the tutelage of the god Seth, the goddess Buto and the god Horus similarly presiding over the Lower Kingdom. The royal god in the palace of each was a hawk or Horus. The spirits of the deceased kings were honoured re spectively as the jackal-headed spirits of Nekhen and the hawk headed spirits of Pe. As we hear also of the "Spirits of On" it is probable that Heliopolis was at one time capital of a kingdom. In after days the prehistoric kings were known as "Worshippers of Horus" and in Manetho's list they are the vEicvES, "Dead" and ijpwES, "Heroes," being looked upon as intermediate between the divine dynasties and those of human kings.

It is doubtful whether we possess any writing of the prehistoric age. A few names of the kings of Upper and of Lower Egypt are preserved in the first line of the Palermo stone, but no annals are attached to them.

Archaic

Period.—Names of a number of kings attributable to the 1st dynasty are known from tombs at Abydos. Unfortu nately, with few exceptions they are "Horus titles" in place of personal names by which they were recorded in lists of Abydos and Manetho. Perhaps the earliest king of the dynasty is one whose name has been provisionally read Nar-mer; of him there exists a magnificent carved and inscribed slate palette found at Hieraconpolis with figures of the king and his vizier, war stand ards and prisoners. Another very early king is Aha ; his name is found in two tombs, one at Nagada, north of Thebes and nearly opposite the road to the Red Sea, the other at Abydos. Manetho makes the 1st dynasty "Thinite"; This being the capital of the "nome" in which Abydos lay, Menes must represent either Nar mer or Aha or both. Upper Egypt always had precedence over Lower Egypt and it seems clear that Menes came from the former and conquered the latter. According to tradition he f ounded Mem phis, which lay on the frontier of his conquest ; probably he re sided there as well as at Abydos; at any rate relics of one of the later kings of the 1st dynasty have already been recognized in its vast necropolis. Of the eight kings of the 1st dynasty, three—the fifth, sixth and seventh in the Ramesside list of Abydos—are positively identified by their names on objects from the royal tombs at Abydos and others are scarcely less certain. Two of the kings have also left tablets at the copper and turquoise mines of Wadi Maghara in Sinai. The royal tombs are built of brick, but one of them, that of Usaphais, had its floor of granite from Ele phantine. They must have been filled with magnificent furniture and provisions of every kind, including even annual record-tablets of the reigns, carved in ivory and ebony. The annals of the Palermo stone commenced with the 1st dynasty.The and dynasty of Manetho appears to have been separated from the 1st even on the Palermo stone; it also was Thinite, and the tombs of several of its nine ( ?) kings were found at Abydos. The 3rd dynasty is given as Memphite by Manetho. Two of the kings built huge mastaba-tombs at Bet Khallaf near Abydos, but the architect and learned scribe Imhotp designed for one of these two kings, named Zoser, a second and mightier monument at Memphis, the great step-pyramid of Sakkara with all its wonderful appurtenances. Zoser and Imhotp built also at Heliopolis. (In Ptolemaic times Imhotp received the honour of deification.) Monuments and written records are henceforth more numerous and important, and the fragments of the Palermo annals show a very full scale of record for the reign of Snefru at the end of this dynasty. The events in the three years that are preserved in clude a successful raid upon the Nubians and the construction of ships and gates of cedar-wood which must have been brought from the forests of the Lebanon. Snefru also set up a tablet at Wadi Maghara in Sinai. He built two pyramids, one of them at Medum in steps, the other, probably in the perfected form, at Dahshur, both lying between Memphis and the Fayum.

The Pyramid Period.—Pyramids did not cease to be built in Egypt till the New Kingdom; but from the end of the 3rd to the 6th dynasty is pre-eminently the time when the royal pyramid in stone was the chief monument left by each successive king. Zoser and Snefru have been already noticed. The personal name enclosed in a cartouche pi is henceforth the commonest title of the king. We now reach the 4th dynasty containing the famous Herodotean names of Cheops (q.v.), Chephren (Khafre) and Mycerinus (Menkeure), builders respectively of the Great, the Second and the Third Pyramids of Giza. In the best art of this time there was a grandeur which was never again attained. Per haps the noblest example of Egyptian sculpture in the round is a diorite statue of Chephren, one of several found by Mariette in the so-called Temple of the Sphinx. This "temple" proves to be a monumental gate at the lower end of the great causeway leading to the plateau on which the pyramids were built. A king Dedef re, between Cheops and Chephren, built a pyramid at Abu-Roash. Shepseskaf is one of the last in the dynasty. Tablets of most of these kings have been found at the mines of Wadi Maghara. In the neighbourhood of the pyramids there are numerous mastabas of the court officials with fine sculpture in the chapels, and a few decorated tombs from the end of this centralized dynasty of abso lute monarchs are known in Upper Egypt. A tablet which de scribes Cheops as the builder of various shrines about the Great Sphinx has been shown to be a priestly forgery, but the Sphinx itself may have been carved out of the rock under the splendid rule of the 4th dynasty.

The 5th dynasty is said to be of Elephantine, but this must be a mistake. Its kings worshipped Re, the sun, rather than Horus, as their ancestor, and the title V2 "son of the Sun" began to be written by them before the cartouche containing the personal name, while another "solar" cartouche, containing a name corn pounded with Re, followed the title "king of Upper and 0 0 Lower Egypt." Sahure and the other kings of the dynasty built magnificent temples with obelisks dedicated to Re, one of which, that of Neuserre at Abusir has been thoroughly explored. The marvellous tales of the Westcar Papyrus, dating from the Middle Kingdom, narrate how three of the kings were born of a priestess of Re. The pyramids of several of the kings are known. The early ones are at Abusir, and the best preserved of the pyramid temples, that of Sahure, excavated by the German Orient-Gesellschaft, in its architecture and sculptured scenes, has revealed an astonishingly complete development of art and architecture as well as warlike enterprise by sea and land at this remote period ; the latest pyra mid belonging to the 5th dynasty, that of Unas at Sakkara, is inscribed with long ritual and magical texts. Exquisitely sculptured tombs of this time are very numerous at Memphis and are found throughout Upper Egypt. Of work in the traditional temples of the country no trace remains, probably because, being in lime stone, it has all perished. The annals of the Palermo stone were engraved and added to during this dynasty; the chief events re corded for the time are gifts and endowments for the temples. Evidently priestly influence was strong at the court. Expeditions to Sinai and Puoni (Punt) are commemorated on tablets.

The 6th dynasty if not more vigorous was more articulate ; in scribed tombs are spread throughout the country. The most active of its kings was the third, named Pepi or Phiops, from whose pyramid at Sakkara the capital, hitherto known as "White Walls," derived its later name of Memphis (MN–NFR, Mempi) ; a tomb stone from Abydos celebrates the activity of a certain Una during the reigns of Pepi and his successor in organizing expeditions to the Sinai peninsula and south Palestine, and in transporting granite from Elephantine and other quarries. Herkhuf, prince of Elephan tine and an enterprising leader of caravans to the south countries both in Nubia and the Libyan oases, flourished under Merenre and Pepi II. called Neferkere. On one occasion he brought home a dwarf dancer from the Sudan, described as being like one brought from Puoni in the time of the 5th dynasty king Asesa; this drew from the youthful Pepi II. an enthusiastic letter which was en graved in full upon the façade of Herkhuf's tomb. The reign of the last-named king, begun early, lasted over 90 years, a fact so long remembered that even Manetho attributes to him 94 years; its length probably caused the ruin of the dynasty. The local prince lings and monarchs had been growing in culture, wealth and power, and after Pepi II. an ominous gap in the monuments, pointing to civil war, marks the end of the Old Kingdom.

The Early Intermediate Period.

The 7th and 8th dynasties are said to have been Memphite, but of them scarcely any record survives beyond some names of kings in the lists. Literary texts record a complete upset of social order and the intrusion of an invading race. The duration of this dark and miserable period is unknown. The long Memphite rule was broken by the 9th and loth dynasties of Heracleopolis Magna (tines) in Middle Egypt They may have spread their rule by conquest over Upper Egypt and then overthrown the Memphite dynasty. Kheti or Achthoes was apparently a favourite name with the kings, but they are very obscure. It would seem that after they in turn were overthrown their monuments at Heracleopolis were systematically destroyed. The chief relics of the period are certain inscribed tombs at Assiut; it appears that one of the kings, whose praenomen was Mikere, supported by a fleet and army from Upper Egypt, and especially by the prince of Assiut, was restored to his paternal city of Hera cleopolis, from which he had been driven out ; his pyramid, how ever, was built in the old royal necropolis at Memphis.

The Middle Kingdom.

The princes of Thebes asserted their independence and founded the nth th dynasty, which pushed its frontiers northwards until finally it occupied the whole country. Its kings were named Menthotp (from Mont, one of the gods of Thebes) and Antef, and were buried at Thebes, Nibhotp Menthotp I. probably established his rule over all Egypt. The funerary temple of Nebhepre Menthotp III., the last but one of these kings, has been excavated by the Egypt Exploration Fund at Deir el Bahri, and must have been a magnificent monument. His successor, Sankhkere Menthotp IV. is known to have sent an expedition by the Red sea to Puoni.Monuments of the Theban i 2th dynasty are abundant and often of splendid design and workmanship, whereas previously there had been little produced since the 6th dynasty that was not half bar barous. Although not much of the history of the i 2th dynasty is ascertained, the Turin papyrus and many dated inscriptions fix the succession and length of reign of the eight kings very accurate ly. The troubled times that the kingdom had passed through taught the long-lived monarchs the precaution of associating a competent successor on the throne. The "nomarchs" and the other feudal chiefs were inclined to strengthen themselves at the expense of their neighbours; a firm hand was required to hold them in check and distribute the honours as they were earned by faithful service. The tombs of the most favoured and wealthy princes are magnificent, particularly those of certain families in Middle Egypt at Beni Hasan, El Bersha, Assiut and Deir Rifa, and it is probable that each had a court and organization within his districts or "nome" like that of the royal palace in miniature. Eventually, in the reigns of Senwosri III. and Amenemhe III. the succession of strong kings appears to have centralized all authority very com pletely. The names in the dynasty are Amenemhe (Ammenemes) and Senwosri (formerly read Usertsen or Senusert). The latter seems to be the origin of Sesostris (q.v.) of the legends. Amen emhe I., the first king, whose connection with the previous dynasty is not known, reigned for 3o years, ten of them being in partner ship with his son Senwosri I. He had to fight for his throne and then reorganize the country, removing his capital or residence from Thebes to a central situation near Lisht, about 25m. south of Memphis. His monuments are widespread in Egypt, the quarries and mines in the desert as far as Sinai bear witness to his great activity, and we know of an expedition which he made against the Nubians. The "Instructions of Amenemhe to his son Senwosri," whether really his own or a later composition, refer to these things, to his care for his subjects, and to the ingratitude with which he was rewarded, an attempt on his life having been made by the trusted servants in his own palace. The story of Sinuhi is the true or realistic history of a soldier, who having overheard the secret intelligence of Amenemhe's death, fled in fear to Palestine or Syria and there became rich in the favour of the prince of the land ; growing old, however, he successfully sued for pardon from Senwosri and permission to return and die in Egypt.

Senwosri I. was already the executive partner in the time of the co-regency, warring with the Libyans and probably in the Sudan: After Amenemhe's death he fully upheld the greatness of the dy nasty in his long reign of 45 years. The obelisk of Heliopolis is amongst his best-known monuments, and the damming of the Lake of Moeris (q.v.) must have been in progress in his reign. He built a temple far up the Nile at Wadi Half a and there set up a stela commemorating his victories over the tribes of Nubia. The fine tombs of Ameni at Beni Hasan and of Hepzefa at Assiut be long to his reign. The pyramids of both father and son are at Lisht.

Amenemhe II. was buried at Dahshur; he was followed by Sen wosri II., whose pyramid is at Illahun at the mouth of the Fayum. In his reign were executed the fine paintings in the tomb of Khnem hotp at Beni Hasan, which include a remarkable scene of Semitic Bedouins bringing eye-paint to Egypt from the eastern deserts. In Manetho he is identified with Sesostris (see above), but Senwosri I. and still more Senwosri III. have a better claim to this distinc tion. The latter warred in Palestine and in Nubia, and marked the south frontier of his kingdom by a statue and stelae at Semna be yond the Second Cataract. Near his pyramid was discovered the splendid jewellery of some princesses of his family. The tomb of Thethotp at El Bersha, celebrated for the scene of the trans port of a colossus amongst its paintings was finished in this reign.

Amenemhe III. completed the work of Lake Moeris and began a series of observations of the height of the inundation at Semna which was continued by his successors. In his reign of 46 years he built a pyramid at Dahshur, and at Hawara near the Lake of Moeris another pyramid, together with the Labyrinth which seems to have been an enormous funerary temple attached to the pyra mid. His name was remembered in the Fayum during the Graeco Roman period and his effigy worshipped there as Pera-marres; i.e., Pharaoh Marres (Marres being his praenomen graecized). Amen emhe IV.'s reign was short, and the dynasty ended with a queen Sebeknefru (Scemiophris), whose name is found in the scanty re mains of the Labyrinth. The i 2th dynasty numbered eight rulers and lasted for 213 years. Great as it was, it created no empire outside the Nile valley, and the Labyrinth, its most imposing monument, which according to the testimony of the ancients rivalled the pyramids, is now represented only by a vast bed of quarrymen's chips.

The Later Intermediate Period.

The history of this is very obscure. Manetho gives us the 13th (Diospolite) dynasty, the 14th (Xoite from Xois in Lower Egypt), the 15th and 16th (Hyksos) and the 17th (Diospolite) but his names are lost except for some Hyksos kings. The Abydos tablet ignores all between the 12th and 18th dynasties. The Turin papyrus preserves many names on its shattered fragments, and the monuments are for ever adding to the list, but it is difficult to assign them accurately to their places. The Hyksos names can in some cases be recognized by their foreign aspect, the peculiar style of the scarabs on which they are engraved or by resemblances to those recorded in Manetho. The kings of the 17th dynasty too are generally recognizable by the form of their name and other circumstances. Manetho indicates marvellous crowding for the 12th and 54th dynasties, but it seems better to suggest a total duration of 300 or 40o years for the whole period than to adopt Meyer's estimate of about 210 years.Amongst the kings of the 13th dynasty (including perhaps the 14th) not a few are represented by granite statues of colossal size and fine workmanship, especially at Thebes and Tanis, some by architectural fragments, some by graffiti on the rocks about the First Cataract. Some few certainly reigned over all Egypt. Sebkhotp is a favourite name, no doubt to be connected with the god of the Fayum. Several of the Theban kings named Antef must be placed here rather than in the 11th dynasty. A decree of one of them degrading a nomarch who had sided with his enemies was found at Coptos engraved on a doorway of Senwosri I.

In its divided state Egypt would fall an easy prey to the for eigner. Manetho says that the Hyksos (q.v.) gained Egypt without a blow. Their domination must have lasted a considerable time, the Rhind mathematical papyrus having been copied in the 33rd year of a king Apophis. The monuments and scarabs of the Hyksos kings are found throughout Upper and Lower Egypt and even in Nubia ; those of Khian somehow spread as far as Crete and Bagh dad. The Hyksos, in whom Josephus recognized the children of Israel, worshipped their own Syrian deity, identifying him with the Egyptian god Seth, and endeavoured to establish his cult throughout Egypt, to the detriment of the native gods. It is to be hoped that definite light may one day be forthcoming on the whole of this critical episode which had such a profound effect on the character and history of the Egyptian people. The spirited overthrow of the Hyksos ushered in the glories in arms and arts which marked the New Empire. The 17th dynasty, in which the chief names are Seqenenre and Kamosi, probably began the strug gle, at first as semi-independent kinglets at Thebes. The mummy of Seqenenre, the earliest in the great find of royal mummies at Deir el Bahri, shows the head frightfully hacked and split, perhaps in a battle with the Hyksos.

The New Empire.

The epithet "new" is generally attached to this period, and "empire" instead of "kingdom" marks its wide conquests and organized rule abroad. The glorious i 8th dynasty seems to have been closely related to the i 7th. Its first task was to crush the Hyksos power in the north-east of the Delta ; this was fully accomplished by its founder Ahmosi (or Amasis) cap turing their great stronghold of Avaris. Amasis next attacked them in south-west Palestine, where he captured Sharuhen after a siege of three years. He fought also in Nubia, besides overcoming fac tious opposition in his own land. The principal source for the history of this time is the biographical inscriptions at El Kab of a namesake of the king, Ahmosi son of Abana, a sailor and warrior whose exploits extend to the reign of Tuthmosis I. Amenophis I. (Amenhotp) succeeding Amasis, fought in Libya and extinguished finally an Ethiopian kingdom which, centred at Kerma near the Third Cataract, had flourished since the end of the r 2th dynasty, Tuthmosis I. (c. 154o B.c.) was perhaps of another family, but obtained his title to the throne through his wife Ahmosi. After some 3o years of settled rule uninterrupted by revolt, Egypt was now strong enough and rich enough to indulge to the full its new taste for war and lust of conquest. It had become essentially a military state. The whole of the administration was in the hands of the king with his vizier and other court officials ; no trace of the feudalism of the Middle Kingdom survived. Tuthmosis thoroughly subdued Cush, which had already been placed under the govern ment of a viceroy, whose dominion extended from Napata just below the Fourth Cataract on the south to El Kab in the north, so that it included the first three "nomes" of Upper Egypt, which agriculturally were not greatly superior to Nubia. Turning next to Syria, Tuthmosis carried his arms as far as the Euphrates. He made the first of those great additions to the temple of the Theban Ammon at Karnak by which the pharaohs of the empire rendered it by far the greatest of the existing temples in the world ; the temple of Deir el Bahri was also designed by him. Towards the end of his reign, his elder sons being dead, Tuthmosis associated Hatshepsut, his daughter by Ahmosi, with himself upon the throne. He was the first of a long line of kings to be buried in the Valley of the Tombs of the Kings at Thebes. A son, Tuthmosis II., succeed ed as the husband of his half-sister Hatshepsut, but reigned only two or three years, during which he warred in Nubia and placed Tuthmosis III., his son by a concubine Esi, upon the throne beside him (c. i 5 oo B.c.) . After her husband's death the ambitious Hat shepsut assumed the full regal power; upon her monuments she wears the masculine garb and aspect of a king, though the feminine gender is retained for her in the inscriptions. On some monuments of this period her name appears alone, on others in conjunction with that of Tuthmosis III., while the latter again may appear without the queen's ; but this extraordinary woman must have had a great influence over her stepson and was the acknowledged ruler of Egypt. Hatshepsut cultivated the arts of peace. She restored the worship in those temples of Upper and Lower Egypt which had not yet recovered from the religious oppression and neglect of the Hyksos. She completed and decorated the temple of Deir el Bahri, embellishing its walls with scenes calculated to establish her claims, representing her divine origin and upbringing under the protection of Ammon, and her association on the throne by her human father. The famous sculptures of the great expedition by water to Puoni, the land of incense on the Somali coast, are also here, with many others. At Karnak, Hatshepsut laboured chiefly to complete the works projected in the reigns of Tuthmosis I. and II., and set up two obelisks in front of the entrance as it then was. One of these, still standing, is the most brilliant ornament of that wonderful temple. A date of the 22nd year of her reign has been found at Sinai, no doubt counted from the beginning of the co regency with Tuthmosis I. Not much later, in his 2 2nd year, Tuth mosis III. is reigning alone in full vigour. While she lived, the per sonality of the queen secured the devotion of her servants and held all ambitions in check. Not long after her death there was a vio lent reaction. Prejudice against the rule of a woman, particularly one who had made her name and figure so conspicuous, was prob ably the cause of this outbreak, and perhaps sought justification in the fact that, however complete was her right, she had in some degree usurped a place to which her stepson (who was also her nephew) had been appointed. Her cartouches began to be defaced or her monuments hidden by other buildings, and the same rage pursued some of her most faithful servants in their tombs. But the beauty of the work seems to have restrained the hand of the destroyer. Then came the religious fanaticism of Ikhnaton, mu tilating all figures of Ammon and all inscriptions containing his name; this made havoc of the exquisite monuments of Hatshep sut ; and the restorers of the i 9th dynasty, ref using to recognize the legitimacy of the queen, had no scruples in replacing her names by those of the associate kings, Tuthmosis I., II. or III. In the royal lists of Sethos I. and Rameses II., Hatshepsut has no place, nor is her reign referred to on any later monument.The immense energy of Tuthmosis III. now found its outlet in war. Syria had revolted, perhaps on Hatshepsut's death, but by his 22nd year the monarch was ready to lead his army against the reb els. Unlike his predecessors, who merely overran one of ter another a series of isolated city states, Tuthmosis had to face the organized resistance of a large combination, embracing the whole of western Syria and headed by the city of Kadesh on the Orontes. Six care fully planned campaigns had to be fought in order to reach and capture that city. In the 33rd year of his reign he marched through Kadesh, fought his way to Carchemish, defeated the forces that opposed him there and crossed over the Euphrates into the territory of the king of Mitanni. In all he fought i 7 campaigns in Syria until the spirit of revolt was entirely crushed in a second capture of Kadesh. The wars in Libya and Ethiopia were of less moment. In the intervals of war Tuthmosis III. proved himself a wonderfully efficient administrator, with his eye on every corner of his dominions. The Syrian expeditions occupied six months in most of his best years, but the remaining time was spent in activity at home, repressing robbery and injustice, rebuilding and adorning temples with the labour of his captives and the plunder and tribute of conquered cities, or designing with his own hand the gorgeous sacred vessels of the sanctuary of Ammon. In his later years some expeditions took place into Nubia. The children of the subdued princelings in Asia and elsewhere were taken as hostages to Egypt and there educated to succeed their fathers with a due understand ing of the might of Pharaoh both to protect and to punish. Thus was an empire established on a sound basis, probably for the first time in history. Tuthmosis died in the 54th year of his reign. His mummy, found in the cachette at Dair al-Bahri is remarkable for the low forehead; yet we consider him the greatest of all the Pharaohs.

Tuthmosis III. was succeeded by his son Amenophis II., whom he had associated on the throne at the end of his reign. One of the first acts of the new king was to lead an army into Syria where revolt was again rife ; he reached and perhaps crossed the Eu phrates and returned home to Thebes with seven captive kings of Tikhsi and much spoil. The kings he sacrificed to Ammon and hanged six bodies on the walls, while the seventh was carried south to Napata and there exposed as a terror to the Ethiopians. Ameno phis reigned 26 years and left his throne to his son, Tuthmosis IV., who is best remembered by a granite tablet recording his clear ance of the Great Sphinx. He also warred in northern Syria and in Cush. His son, Amenophis III. (c. i400 B.c.), was a mighty build er, especially at Thebes, where his reign marks a new epoch in the history of the great temples, Luxor being his creation, while ave nues of rams, pylons, etc., were added on a vast scale to Karnak. He married a certain Taia, who, though apparently of humble parentage, was held in great honour by her husband as afterwards by her son. Amenophis III. warred in Ethiopia, but his sway was long unquestioned from Napata to the Euphrates. Small objects with his name and that of Taia are found on the mainland and in the islands of Greece. Through the fortunate discovery of cunei form tablets deposited by his successor in the archives at Tell el Amarna, we can see how the rulers of the great kingdoms beyond the river, Mitanni, Assyria and even Babylonia, corresponded with Amenophis, gave their daughters to him in marriage and congratu lated themselves on having his friendship. Within the empire the descendants of the Syrian dynasts conquered by his father, having been educated in Egypt, ruled their paternal possessions as the abject slaves of Pharaoh. A constant stream of tribute poured into Egypt, sufficient to defray the cost of all the splendid works that were executed. Amenophis caused a series of large scarabs unique in their kind to be engraved with the name and parentage of his queen Taia, followed by varying texts commemorating like medals the boundaries of his kingdom, his secondary marriage with Gilukhipa, daughter of the king of Mitanni, the formation of a sacred lake at Thebes, a great hunt of wild cattle, and the number of lions the king slew in the first ten years of his reign. The colossi known to the Greeks by the name of the Homeric hero Memnon which look over the western plain of Thebes, represent this king and were placed before the entrance of his funerary temple, the rest of which has disappeared. His palace lay farther south on the west bank, built of crude brick covered with painted stucco. To wards the end of his reign of 36 years, Syria was invaded by the Hittites from the north and the people called Khabiri from the eastern desert ; some of the kinglets conspired with the invaders to overthrow the Egyptian power, while those who remained loyal sent alarming reports to their sovereign.

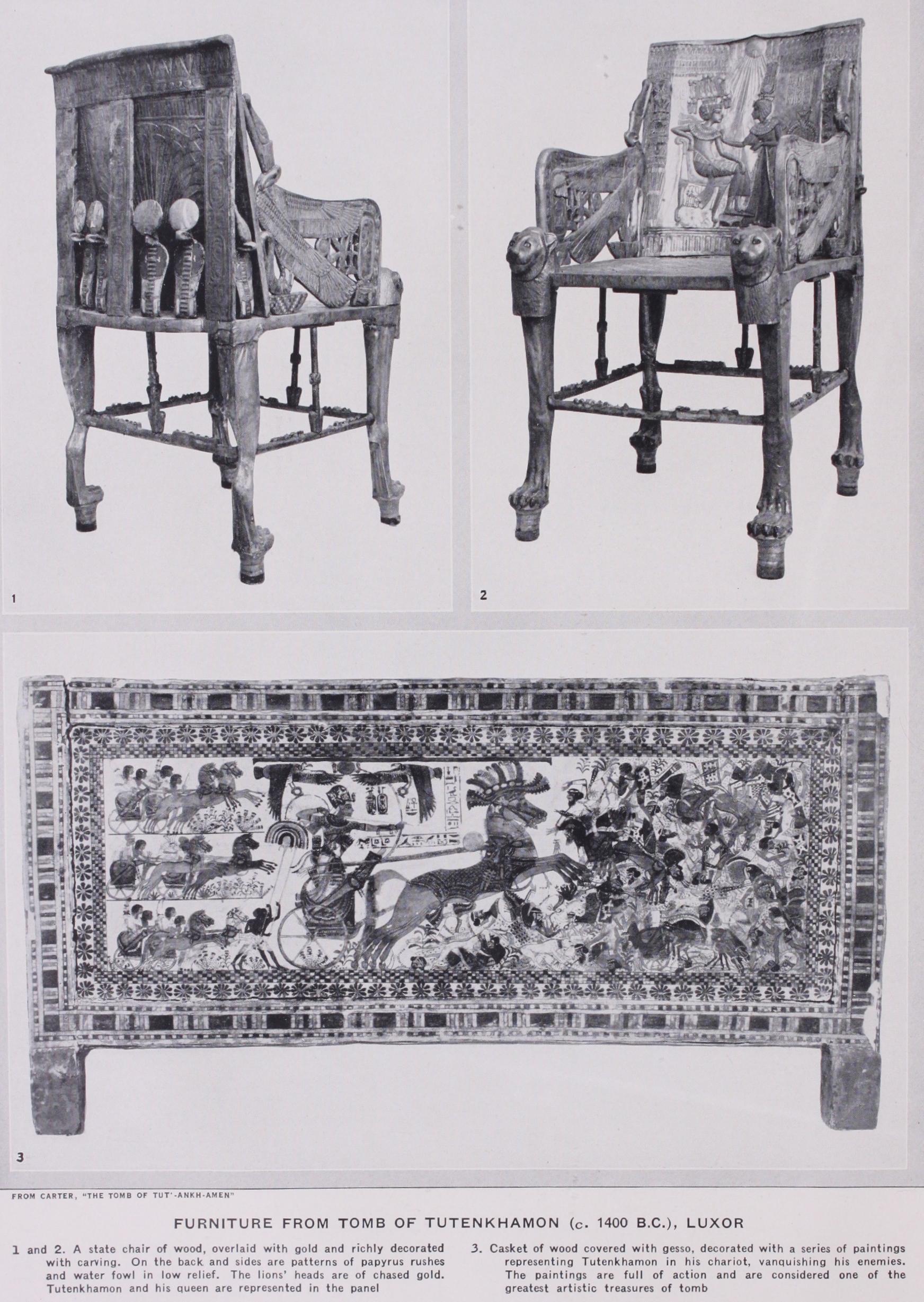

Amenophis IV., son of Amenophis III. and Taia, was perhaps the most remarkable character in the long line of the Pharaohs. He was a religious fanatic, who had probably been high priest of the sun-god at Heliopolis, and had come to view the sun as the vis ible source of life, creation, growth and activity, whose power was demonstrated in foreign lands almost as clearly as in Egypt. Thrusting aside all the multitudinous deities of Egypt and all the mythology even of Heliopolis, he devoted himself to the cult of the visible sun-disc, applying to it as its chief name the hitherto rare word Aton, meaning "sun" ; the traditional divine name Harakht (Horus of the horizon), given to the hawk-headed sun god of Heliopolis, was however allowed to subsist and a temple was built at Karnak to this god. The worship of the other gods was officially recognized until his fifth year, but then a sweeping re form was initiated by which apparently the new cult alone was per mitted. Of the old deities Ammon represented by far the wealth iest and most powerful interests, and against this long-favoured deity the Pharaoh hurled himself with fury. He changed his own name from Amenhotep, "Ammon is satisfied," to Ikhnaton, "pious to Aton," erased the name and figure of Ammon from the monu ments, even where it occurred as part of his own father's name, abandoned Thebes, the magnificent city of Ammon, and built a new capital at El Amarna in the plain of Hermopolis, on a virgin site upon the edge of the desert. This with a large area around he dedicated to Aton in the sixth year while splendid temples, palaces, houses and tombs for his god, for himself and for his courtiers were rising around him. In all local temples the worship of Aton was instituted. The confiscated revenues of Ammon and the trib ute from Syria and Cush provided ample means for adorning Akhetaton, "the horizon of Aton," the new capital, and for richly rewarding those who adopted the Aton teaching fervently. But meanwhile the political needs of the empire were neglected; the dangers which threatened it at the end of the reign of Amenophis III. were never properly met ; the dynasts in Syria were at war amongst themselves, intriguing with the great Hittite advance and with the Khabiri invaders. Those who relied on Pharaoh and re mained loyal as their fathers had done sent letter after letter appeal ing for aid against their foes. But though a general was despatched with some troops, he seems to have done more harm than good in misjudging the quarrels. At length the tone of the letters becomes one of despair, in which flight to Egypt appears the only resource left for the adherents of the Egyptian cause. Before the end of the reign Egyptian rule in Syria had probably ceased altogether. Ikhnaton died in or about the 17th year of his reign, c. 1350 B.C. He had a family of daughters who appeared constantly with him in all ceremonies, but no son. Two sons-in-law, mere boys, fol lowed him with brief reigns, but the second, Tutankhaton, soon changed his name to Tutenkhamon and without abandoning Ak hetaton entirely, began to restore to Karnak its ancient splendour, with new monuments dedicated to Ammon. Ikhnaton's reform had not reached deep amongst the masses of population; they probably retained all their old religious customs and superstitions, while the priesthoods throughout the country must have been fiercely opposed to the heretic's work, even if silenced during his lifetime by force and bribes. Tutenkhamon died of ter six years of reign and was buried at Thebes in the famous tomb which Lord Carnarvon and Howard Carter found still packed with its precious furniture. One more adherent of Ikhnaton, a priest named Ay, ruled for a short time. At length a soldier Haremhab, came to the throne as a whole-hearted supporter of the old religion without the heretical family taint of his predecessors ; soon Aton and the whole of his royal following suffered the fate they had imposed upon Ammon; their monuments were destroyed and their names and figures erased, while those of Ammon were restored. From the time of Rameses II. onwards the years of the reigns of the heretics were counted to Haremhab, and Ikhnaton was described as "that criminal of Akhetaton." Haremhab had to bring order as a prac tical man into the long-neglected administration of the country and to suppress the extortions of the official classes by severe measures. His laws to this end were engraved on a great stela in the temple of Karnak, of which sufficient remains to bear witness to his high aims, while the prosperity of the succeeding reigns shows how well he realized the necessities of the state. He prob ably began also to re-establish the prestige of Egypt by military expeditions in the surrounding countries.

Haremhab appears to have legitimated his rule by marriage to a royal princess, but it is probable that Rameses I. who succeeded as founder of the 19th dynasty, was not closely related to him. Ram eses in his brief reign of two years planned and began the great col onnaded hall of Karnak. His son, Seti I., having subdued the Bed ouin Shasu, who had invaded Palestine and withheld all tribute, proceeded to the Lebanon. Here cedars were felled for him by the Syrian princes, and the Phoenicians paid homage before he re turned home in triumph. The Libyans had also to be dealt with, and afterwards Seti advanced again through Palestine, ravaged the land of the Amorites and came into conflict with the Hittites. The latter, however, were now firmly established in the Orontes valley, and a treaty with Mutallu, the king of Kheta, reigning far away in Cappadocia, probably ended the wars of Seti. In his ninth year he turned his attention to the gold-mines in the eastern desert of Nubia and improved the road thither. Meanwhile the great work at Karnak projected by his father was going forward, and through out Egypt the injuries done to the monuments by Ikhnaton were thoroughly repaired; the erased inscriptions and figures were re stored, not without many blunders. Seti's temple at Abydos and his galleried tomb in the Valley of the Tombs of the Kings stand out as the most splendid examples of their kind in design and in decoration. Rameses II. succeeded at an early age and reigned 67 years, during which he finished much that was begun by Seti and filled all Egypt and Nubia with his own monuments, some of them beautiful but most, necessarily entrusted to inferior workmen, of coarse execution. The excavation of the rock temple of Abu Simbel and the completion of the great hall of Karnak were his greatest achievements in architecture. His wars began in his sec ond year, their field comprising the Nubians, the Libyans, the Syr ians and the Hittites. In his fifth year, near Kadesh on the Oron tes, his army was caught unprepared and divided by a strong force of chariots of the Hittites and their allies, and Rameses himself was placed in the most imminent danger ; but through his per sonal courage the enemy was kept at bay till reinforcements came up and turned the disaster into a victory. The incidents of this episode were a favourite subject in the sculptures of his temples, where their representation was accompanied by a poetical version of the affair and other explanatory inscriptions. Kadesh, however, was not captured, and after further contests, in his 21st year, Rameses and the Hittite king Khattusil (Kheta-sar) made peace, with a defensive alliance against foreign aggression and internal revolt (see HITTITES). In the 34th year, c. 125o B.C., Khattusil with his friend or subject, the king of Kode, came from his dis tant capital to see the wonders of Egypt in person, bringing one of his daughters to be wife of the splendid Pharaoh. Rameses II. paid much attention to the Delta, which had been neglected until the days of Seti I., and resided there constantly; the temple of Tanis must have been greatly enlarged and adorned by him; a colossus of the king placed here was over 9of t. in height, exceeding in scale even the greatest of the Theban colossi which he had erected in his mortuary temple of the Rameseum. Towards the end of the long reign the vigilance and energy of the old king diminished. The military spirit awakened in the struggle with the Hyksos had again departed from the Egyptian nation ; mercenaries from the Sudan, from Libya and from the northern nations supplied the armies, while foreigners settled in the rich lands of the Delta and harried the coasts. It was a time too when the movements of the nations that so frequently occurred in the ancient world were about to be particularly active. Mineptah, (c. 1225 B.C), succeeding his father Rameses II., had to fight many battles for the preservation of his kingdom and empire. Apparently most of the fighting was finished by the fifth year of his reign; in his mortuary temple at Thebes he set up a stela of that date recording a great victory over the Libyan immigrants and invaders, which rendered the much har ried land of Egypt safe. The last lines picture this condition with the crushing of the surrounding tribes. Libya was wasted, the Hit tites pacified, Canaan, Ashkelon, Gezer, Yenoam sacked and plun dered ; "Israel is desolated, his seed is not, Khor (Palestine) has become a widow (without a protector) for Egypt." The Libyans are accompanied by allies whose names, Sherden, Shekelesh, Ek wash, Lukku, Teresh, suggest identifications with Sardinians, Sicels, Achaeans, Lycians and Tyrseni or Etruscans. The Sherden had been in the armies of Rameses II. and are distinguished by their remark able helmets and, apparently, body armour of metal. The Lukku are certainly the same as the Lycians. Probably they were all sea rovers from the shores and islands of the Mediterranean, who were willing to leave their ships and join the Libyans in raids on the rich lands of Egypt. Mineptah was one of the most unconscion able usurpers of the monuments of his predecessors, including those of his own father, who, it must be admitted, had set him the example. The coarse cutting of his cartouches contrasts with the splendid finish of the Middle Kingdom work which they disfigure. It may be questioned whether it was due to a wave of enthusiasm amongst the priests and people, leading them to re-dedicate the monuments in the name of their deliverer, or a somewhat insane desire of the king to perpetuate his own memory in a singularly unfortunate manner. Mineptah, the 13th son in the huge family of Rameses, must have been old when he ascended the throne ; after his first years of reign his energies gave way, and he was followed by a quick succession of inglorious rulers, Seti II., the queen Tuosri, Amenmesse, Siptah; the names of the last two were erased from their monuments.

A great papyrus written after the death of Rameses III. and recording his gifts to the temples briefly reviews the conditions of the troublous times which preceded his reign. "The land of Egypt was in the hands of chiefs and rulers of towns, great and small slaying each other; afterwards a certain Syrian made himself chief ; he made the whole land tributary before him; he united his companions and plundered their property (i.e., of the other chiefs) . They made the gods like men, and no offerings were presented in the temples. But when the gods inclined themselves to peace . . . they established their son Setnekht to be ruler of every land." Of the Syrian occupation we know nothing further. Set nekht (c. 1200 B.C.), had a very short reign and was not counted as legitimate, but he established a lasting dynasty (probably by con ciliating the priesthood). He was father of Rameses III., who re vived the glories of the empire. The dangers that menaced Egypt were similar to those which Mineptah had to meet at his ac cession. Again the Libyans and the "peoples of the sea" were acting in concert. The latter now comprised Peleset (probably Cretan ancestors of the Philistines) Thekel, Shekelesh, Denyan (Danaoi?) and Weshesh ; they had invaded Syria from Asia Minor, reaching the Euphrates, destroying the Hittite cities and progressing south wards, while their ships gathered plunder from the coasts of the Delta. This fleet joined the Libyan invaders, but was overthrown with heavy loss by the Egyptians, in whose ranks there actually served many Sherdan and Kehaka, Sardinian and Libyan mer cenaries. Egypt itself was thus clear of enemies; but the chariots and warriors of the Philistines and their associates were advancing through Syria, their families and goods following in ox-carts, and their ships accompanying them along the shore. Rameses led out his army and fleet against them and struck them so decisive a blow that the migrating swarm submitted to his rule and paid him trib ute. In his II th year another Libyan invasion had to be met, and his suzerainty in Palestine forcibly asserted. His vigour was equal to all these emergencies and the later years of his reign were spent in peace. Rameses III., however, was not a great ruler. He was possessed by the spirit of decadence, imitative rather than orig inating. It is evident that Rameses II. was the model to which he endeavoured to conform, and he did not attempt to preserve him self from the weakening influences of priestcraft. To the temples he not only restored the property which had been given to them by former kings, but he also added greatly to their wealth, the Theban Ammon receiving by far the greatest share. The land held in the name of different deities is estimated at about 15% of the whole of Egypt ; various temples of Ammon owned two-thirds of this, Re of Heliopolis and Ptah of Memphis being next in wealth. His palace was at Medinet Habu on the west bank of Thebes in the south quarter; and here he built a great temple to Ammon, adorned with scenes from his victories and richly provided with divine offerings. Shortly before the death of the old king a plot in the harem to assassinate him and apparently to place one of his sons on the throne, was discovered and its investigation ordered, leading after his death to the condemnation of many high-placed men and women. Nine kings of the name of Rameses now followed each other ingloriously in the space of about 8o years to the end of the loth dynasty, the power of the high priests of Ammon ever growing at their expense. The Libyans began again their encroach ments, and there was undoubtedly great distress amongst certain portions of the population. We read in a papyrus of a strike of starving labourers in the Theban necropolis who would not work until corn was given to them, and apparently the government storehouse was empty at the time, perhaps in consequence of a bad Nile. At this time the Theban necropolis was being more systematically robbed than ever before. Under Rameses IX. an investigation took place which showed that one of the royal tombs before the western cliffs had been completely ransacked and the mummies burnt. Three years later the Valley of the Tombs of the Kings was attacked and the sepulchres of Seti I. and Rameses II. were robbed. The authority of the last king of the loth dy nasty, Rameses XII., was shadowy. Hrihor, the high priest, gath ered into his own hands the real power, and succeeded him at Thebes, c. II00 B.C.

The Libyan Dynasties in the Delta.

At this juncture a prince at Tanis named Smendes, (Esbenteti) founded a separate dynasty in the Delta (21st dynasty). From this period dates a re markable papyrus containing the report of an envoy named Unamfin, sent to Syria by Hrihor with a recommendation to Smendes, in order to obtain cedar timber from Byblus ; Unamfin learned to his cost that the ancient prestige of Egypt in Syria had entirely disappeared. The Tanite line of kings generally had the overlordship of the high priests of Thebes ; the descendants of Hrihor, however, sometimes by marriage with princesses of the other line, could assume cartouches and royal titles, and in some cases perhaps ruled the whole of Egypt. Ethiopia may have been ruled with the Thebais, but the records of the time are very scanty. The mummies from the despoiled tombs of the kings were the object of much anxious care to the kings of this dynasty; after being removed from one tomb to another, they were finally deposited in a shaft near the temple of Deir el Bahri, where they remained till our day. Eventually these royal mummies were all secured for the Cairo museum.Libyan soldiers had long been employed in the army, and their military chiefs settled in the large towns and acquired wealth and power, while the native rulers grew weaker and weaker. The Tanite dynasty may have risen from a Libyan stock, though there is noth ing to prove it ; the 22nd dynasty are clearly, from their names, of foreign extraction, and their genealogy indicates distinctly a Lib yan military origin in a family of rulers of Heracleopolis Magna in Middle Egypt. Sheshonk (Shishak) I., the founder of the dynasty, (c. 95o B.e.), seems to have fixed his residence at Bubastis in the Delta, and his son married the daughter of the last king of the Tan ite dynasty. Heracleopolis seems henceforth for several centuries to have been capital of Middle Egypt, which was considered as a more or less distinct province. Sheshonk secured Thebes, making one of his sons high priest of Ammon, and whereas Solomon ap pears to have dealt with a king in Egypt on something like an equal footing, Sheshonk re-established Egyptian rule in Palestine and Nubia and his expedition in the fifth. year of Rehoboam subdued Israel as well as Judah, to judge by the list of city names which he inscribed on a wall of the temple of Karnak. Osorkon I. in herited a prosperous kingdom from his father, but no further progress was made. It required a strong hand to curb the Libyan chieftains, and divisions soon began to show themselves in the kingdom. The 22nd dynasty lasted through many generations; but there were rival kings, and it seems that the 23rd dynasty was con temporaneous with the end of the 22nd. The kings of the 23rd dy nasty had little hold upon the subject princes, who spent the resources of the country in feuds amongst themselves. A separate kingdom had meanwhile been established in Ethiopia, probably under a Libyan chieftain. Our first knowledge of it is at this moment, when the Ethiopian king Pankhi, already held the The bais. The energetic prince of Sais, Tefnakht, followed by most of the princes of the Delta, subdued most of Middle Egypt, and by uniting these forces, threatened the Ethiopian border. Heracle opolis Magna, however, with its petty king Pefteuaubasti, held out against Tefnakht, and Pankhi coming to its aid not only drove Tefnakht out of Middle Egypt, but also captured Memphis and received the submission of the princes and chiefs; in all, these in cluded four "kings" and fourteen other chiefs. According to Diodorus the Ethiopian state was theocratic, ruled through the king by the priests of Ammon. The account is probably exagger ated ; but even in Pankhi's record the piety of the king, especially towards Ammon, is very marked.

The 24th dynasty consisted of a single Saite king named Boc choris (Bekerrinf), son of Tefnachthus, apparently the above Tef nakht. Another Ethiopian invader, Shabako (Sabacon) is said to have burnt Bocchoris alive.' The Ethiopian rule of the 25th dy nasty was now firmly established, and the resources of the two countries together might have been employed in conquest of Syria and Phoenicia ; but at this very time the Assyrian empire, risen to the highest pitch of military greatness, began to menace Egypt. The Ethiopian could do no more than encourage or support the Syrians in their fight for freedom against Sargon and Sennacherib. Shabako was followed by Shebitku and Shebitku by Tirhaka. Tir haka was energetic in opposing the Assyrian advance, but in 671 B.C., Esarhaddon defeated his army on the border of Egypt, cap tured Memphis with the royal harem and took great spoil. The Egyptian resistance to the Assyrians was probably only half-heart ed ; in the north especially there must have been a strong party against Ethiopian rule. Tirhaka laboured to propitiate the north country, and probably rendered the Ethiopian rule more acceptable throughout Egypt. Notwithstanding, the Assyrian king entrusted the Government and collection of tribute to the native chiefs; twenty princes in all are enumerated in the records, including one Assyrian to hold the key of Egypt at Pelusium. Scarcely had Esarhaddon withdrawn before Tirhaka returned from his refuge in the south and the Assyrian garrisons were massacred. Esarhad don promptly prepared a second expedition, but died on the way to Egypt in 668 B.c. ; his son, Assur-bani-pal sent it forward, routed Tirhaka and reinstated the governors. At the head of these was Necho (Niku), king of Sais and Memphis, father of Psammeti chus, who founded the 26th dynasty, and no doubt was related to Bocchoris and Tefnakht, the victims of Ethiopian invasion. We next hear that correspondence with Tirhaka was intercepted, and that Necho, together with Pekrur of Psapt (at the entrance to the Wadi Tumilat) and the Assyrian governor of Pelusium, was taken 'Bocchoris is represented by Mycerinus in Herodotus, but confused with Menkeure of the 14th dynasty, whose name is correctly rendered as Mencheres by Manetho.

to Nineveh in chains to answer the charge of treason. Whatever may have occurred, it was deemed politic to send Necho back loaded with honours and surrounded by a retinue of Assyrian offi cials. Upper Egypt, however, was loyal to Tirhaka, and even at Memphis the burial of an Apis bull was dated by the priests as in his reign. Immediately afterwards he died. His nephew Tanda mane, received by the upper country with acclamations, besieged and captured Memphis, Necho being probably slain in the en counter. But in 66i (?) Assur-bani-pal drove the Ethiopian out of Lower Egypt, pursued him up the Nile and sacked Thebes. This was the last and most tremendous visitation of the Assyrian scourge. All the Ethiopian kings from Pankhi to Tandamane were buried in pyramids at their ancestral home at Napata.

Psammetichus (Psametk), 664--610 B.C., the son of Necho, suc ceeded his father as a vassal of Assyria in his possessions of Mem phis and Sais, allied himelf with Gyges, king of Lydia, and aided by Ionian and Carian mercenaries, extended and consolidated his power.' By the ninth year of his reign he was in full possession of Thebes. Assur-bani-pal's energies throughout this crisis were en tirely occupied with revolts nearer home, in Babylon, Elam and Arabia. The Assyrian armies triumphed everywhere, but at the cost of complete exhaustion. Under the firm and wise rule of Psammetichus, Egypt recovered its prosperity after terrible losses inflicted by internal wars and the decade of the Assyrian invasions. The revenue went up by leaps and bounds. Psammetichus guarded the frontiers of Egypt with three strong garrisons, placing the Ionian and Carian mercenaries especially at the Pelusian Daphnae in the north-east, from which quarter the most formidable enemies were likely to appear. A great Scythian horde, destroying all be fore it in its southward advance, is said by Herodotus to have been turned back by presents and entreaties. Diplomacy backed up by vigorous preparations may have deterred the Scythians from the dangerous enterprise of crossing the desert to Egypt. Towards the end of his reign he loyally sent support to the Assyrians against the attacks of the Medes and Babylonians.

When Psammetichus began to reign, the situation of Egypt was very different from what it had been under the empire. The devel opment of trade in the Mediterranean and contact with new peo ples and new civilizations in peace and war had given birth to new ideas among the Egyptians and at the same time to a loss of confi dence in their own powers. The Theban supremacy was gone and the Delta was now the wealthy and progressive part of Egypt ; piety increased amongst the masses, unenterprising and unwarlike, but proud of their illustrious antiquity. The Ethiopians had already turned for their models to the times of the ancient supremacy of Memphis, and the sculptures and texts on tomb and temple were made to conform as closely as possible to those of the Old King dom. In non-religious matters, however, the Egyptians were in venting and perhaps borrowing. To enumerate a few examples of this which are already definitely known : we find that the forms of legal and business documents became more precise ; the mechanical arts of casting in bronze on a core and of moulding figures and pottery were brought to the highest pitch of excellence; and por traiture in the round on its highest plane was better than ever be fore, and admirably lifelike, revealing careful study of the external anatomy of the individual.

Psammetichus died in the 54th year of his reign and was suc ceeded by his son Necho, B.C. The Assyrians finally succumbed in 610 and the new Pharaoh prepared an expedition to recover the long-lost possessions of the Egyptian empire in Syria. Josiah alone opposed him with his feeble force at Megiddo and was easily overcome and slain. Necho went forward to the Eu phrates, put the land to tribute and, in the case of Judah at any rate, filled the throne with his own nominee (see JEHOIAKIM). The division of the Assyrian spoil gave its inheritance in the west to Nabopolasser, king of Babylon, who soon despatched his son Nebuchadrezzar to fight Necho. The Babylonian and Egyp tian forces met at Carchemish (605), and the rout of the latter was so complete that Necho relinquished Syria and might have lost Egypt as well had not the death of Nabopolasser recalled 'This, it may be remarked, is the time vaguely represented by the Dodecarchy of Herodotus.

the victor to Babylon. Herodotus relates that in Necho's reign a Phoenician ship despatched from Egypt actually circumnavi gated Africa, and the attempt was made to complete a canal through the Wadi Tumilat connecting the Mediterranean and the Red Sea by way of the Lower Egyptian Nile (see SUEZ). The next king, Psammetichus 594-589 B.C., according to one ac count, visited Syria or Phoenicia, and apparently sent a mercen ary force into Ethiopia as far as Abu Simbel. Pharaoh Hophra (Apries), 7 o B.C., fomented rebellion against the Babylo nian suzerainty in Judah, but accomplished little there. Herodo tus, however, describes his reign as exceedingly prosperous. The mercenary troops at Elephantine mutinied and attempted to de sert to Ethiopia, but were brought back and punished. Later, however, a disastrous expedition sent to aid the Libyans against the Greek colony of Cyrene roused the suspicion and anger of the native soldiery at favours shown to the mercenaries, who of course had taken no part in it. Amasis (Ahmosi) II. was chosen king by the former (5 7o-5 2 5 B.C.) and his swarm of adherents overcame the Greek troops in Apries' pay. None the less Amasis employed Greeks in numbers, and cultivated the friendship of their tyrants. His rule was confined to Egypt (and perhaps Cy prus), but Egypt itself was very prosperous. At the beginning of his long reign of 44 years he was threatened by Nebuchadrezzar; later he joined the league against Cyrus and saw with alarm the fall of his old enemy. A few months after his death, 525 B.c., the invading host of the Persians led by Cambyses reached Egypt and dethroned his son Psammetichus III.

Cambyses at first conciliated the Egyptians and respected their religion; but, perhaps after the failure of his expedition into Ethiopia, he entirely changed his policy. He left Egypt so com pletely crushed that the subsequent usurpation of the Persian throne was marked by no revolt in that quarter. Darius, 521 486 B.c., proved himself a beneficent ruler, and in a visit to Egypt displayed his consideration for the religion of the country. In the great oasis he built a temple to Ammon. The annual trib ute imposed on the satrapy of Egypt and Cyrene was heavy, but it was probably raised with ease. The canal from the Nile to the Red sea was completed or repaired, and commerce flourished. Documents dated in the 34th and 35th years of Darius are not uncommon, but apparently at the very end of his reign, some years after the disaster of Marathon, Egypt was induced to rebel. Xerxes (486-467 B.c.), who put down the revolt with severity, and his successor Artaxerxes (466-425 B.c.), like Cambyses, were hateful to the Egyptians. The disorders which marked the acces sion of Artaxerxes gave Egypt another opportunity to rebel. The leaders were Inaros, the Libyan of Marea, and the Egyptian Amyr taeus. Aided by an Athenian force, Inaros slew the satrap Achaemenes at the battle of Papremis and destroyed his army; but the garrison of Memphis held out, and a fresh host from Per sia raised the siege and in turn besieged the Greek and Egyptian forces on the island of Papremis. At last, after two years, having diverted the river from its channel, they captured and burnt the Athenian ships and quickly ended the rebellion. The reigns of Xerxes II. and Darius II. are marked by no recorded incident in Egypt until a successful revolt about 405 B.C. interrupted the Persian domination.

Monuments of the Persian rule in Egypt are exceedingly scanty. The inscription of Pefteuauneit, priest of Neith at Sais and from his position the native authority who was most likely to be con sulted by Cambyses and Darius, tells of his relations with these two kings. For the following reigns Egyptian documents hardly exist, but some papyri written in Aramaic have been found at Ele phantine and at Memphis. Those from the former locality show that a colony of Jews with a temple dedicated to Yahweh (Je hovah) had established themselves at that garrison and trading post (see AswAN). Herodotus visited Egypt in the reign of Artaxerxes, about 440 B.C. His description of Egypt, partly founded on Hecataeus, who had been there about So years earlier, is the chief source of information for the history of the Saite kings and for the manners of the times, but his statements prove to be far from correct when they can be checked by the scanty native evidence.

Amyrtaeus (Amnertais) of Sais, perhaps a son of Pausiris and grandson of the earlier Amyrtaeus, revolted from Darius II., c. 405 B.c., and Egypt regained its independence for about 6o years. The next king, Nef euret (Nepherites I.) was a Mendesian and founded the 29th dynasty. After Hakor and Nef euret II. the sovereignty passed to the 3oth Dynasty, the last native Egyptian line. Monuments of all these kings are known and art flourished particularly under the Sevennyte kings Nekhtnebf and Nekh tharheb (Nectanebes I. and II.). The former came to the throne when a Persian invasion was imminent, 379 B.C. Hakor had al ready formed a powerful army, largely composed of Greek mer cenaries. This army Nekhtnebf entrusted to the Athenian Cha brias. The Persians, however, succeeded in causing his recall and in gaining the services of his fellow-countryman Iphicrates. The invading army consisted of 200,000 barbarians under Pharnabazus and 20,000 Greeks under Iphicrates. After the Egyptians had experienced a reverse, Iphicrates counselled an immediate ad vance on Memphis. His advice was not followed by Pharnabazus; the Egyptian king collected his forces and won a pitched battle near Mendes. Pharnabazus retreated and Egypt was free.

Nekhtnebf was succeeded by Tachos or Teos, whose short reign was occupied by a war with Persia, in which the king of Egypt secured the services of a body of Greek mercenaries under the Spartan king Agesilaus and a fleet under the Athenian general Chabrias. He entered Phoenicia with every prospect of success, but having offended Agesilaus he was dethroned in a military revolt which gave the crown to Nekhtharheb; but a large Egyp tian party supported a prince of Mendes, who was probably named Khebobesh, and almost succeeded in overthrowing the new pharaoh. Agesilaus defeated the rival pretender and left Nekhtharheb established on the throne; but the opportunity of a decisive blow against Persia was lost. The new king Artaxerxes III. Ochus, determined to reduce Egypt. A first expedition was defeated by the Greek mercenaries of Nekhtharheb, but a second, commanded by Ochus himself, subdued Egypt with no further resistance than that of the Greek garrison of Pelusium. Nekh tharheb, last of the native pharaohs, instead of endeavouring to relieve them retreated to Memphis and fled thence to Ethiopia, (?) B.C.

Ochus treated his conquest barbarously. From this brief re establishment of Persian dominion (counted by Manetho as the 31 st dynasty) no document survives except one papyrus that ap pears to be dated in the reign of Darius III.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-J.

H. Breasted, A History of Egypt from the Bibliography.-J. H. Breasted, A History of Egypt from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest (1905) ; A History of the Ancient Egyptians (1908) ; Ancient Records of Egypt: Historical Documents from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest, edited and translated (Chicago, 1906-1907) ; W. M. F. Petrie, A History of Egypt (from the earliest times to the 3oth dynasty) H. R. Hall, The Ancient History of the Near East (1913) ; G. Maspero, Histoire ancienne des peuples de l'orient (6th ed. 1904) ; The Dawn of Civilization, The Struggle of the Nations, The Passing of the Empires (1904, etc.) ; The Cambridge Ancient History (1923, etc.) ; J. A. Knudtzon, Die el Amarna Tafeln (Leipzig, 1915) ; G. Steindorff, Die Bliitezeit des Pharaonenreichs (18th dynasty) (Bielefeld and Leipzig, end ed. 1926) . LL. G.) The Conquest by Alexander.—When in 332 B.C., after the battle of Issus, Alexander entered Egypt, he was welcomed as a deliverer. The Persian governor had not forces enough to op pose him and he nowhere experienced even the show of resistance. He visited Memphis, founded Alexandria, and went on pilgrimage to the oracle of Ammon (Oasis of Siwa). The god declared him to be his son, renewing thus an old Egyptian convention or belief ; Olympias was supposed to have been in converse with Ammon, even as the mothers of Hatshepsut and Amenophis III. are rep resented in the inscriptions of the Theban temples to have re ceived the divine essence. At this stage of his career the treasure and tribute of Egypt were of great importance to the Macedonian conqueror. He conciliated the inhabitants by the respect which he showed for their religion ; he organized the government of the natives under two officers, who must have been already known to them (of these Petisis, an Egyptian, soon resigned his share into the charge of his colleague Doloaspis, who bears a Persian name). But Alexander designed his Greek foundation of Alexandria to be the capital, and entrusted the taxation of Egypt and the control of its army and navy to Greeks. Early in 331 B.C. he was ready ' to depart, and led his forces away to Phoenicia. A granite gate way to the temple of Khnum at Elephantine bears his name in hieroglyphic, and demotic documents are found dated in his reign. The Ptolemaic Period.—On the division of Alexander's do minions in 323 B.C., Egypt fell to Ptolemy, the son of Lagus, the founder of the Ptolemaic dynasty (see PTOLEMIES) . Under these rulers the rich kingdom was heavily taxed to supply the sinews of war and to support every kind of lavish expenditure. Officials, and the higher ones were nearly all Greeks, were legion, but the whole system was so judiciously worked that there was little dis content amongst the patient peasantry. During the reign of Philadelphus the land gained from the bed of the lake of Moeris was assigned to veteran soldiers; the great armies of the Ptolemies were rewarded or supported by grants of farm lands, and men of Macedonian, Greek and Hellenistic extraction were planted in colonies and garrisons or settled themselves in the villages through out the country. Upper Egypt, farthest from the centre of govern ment at Alexandria, was probably least affected by the new influ ences, though the first Ptolemy established the Greek colony of Ptolemais to be its capital. Intermarriages, however, gradually had their effect ; after the revolt in the reigns of Ptolemy IV. and V. we find the Greek and Egyptian elements closely intermingled. Ptolemy I. had established the cult of the Memphite Serapis in a Graeco-Egyptian form, affording a common ground for native and Hellenistic worshippers, and endless temples to the native deities were built or re-built under the Ptolemies. No serious effort was made to extend the Ptolemaic rule into Ethiopia, and Ergamenes, the Hellenizing king of Ethiopia, was probably in alliance with Philopator; in the last year of Philopator (Ptolemy IV.), 204 B.C., came the great native revolt which continued through most of the reign of Epiphanes and affected the whole country. Down to 186 B.c. Harmakhis and Ankhmakhis native kings supported by Ethio pia reigned in succession at Thebes, and two years later there was still trouble in Lower Egypt. Thebes lost all except its religious importance under the Ptolemies; after the "destruction" or dis mantling by Lathyrus (Ptolemy X.) it formed only a series of villages. The population of Egypt in the time of Ptolemy I. is put at 7,000,000 by Diodorus, who also says that it was greater then than it ever was before ; at the end of the dynasty, in his own day, it was not much less, though somewhat diminished. It is remark able that, while the building and decoration of temples continued in the reigns of Ptolemy Auletes (XIII.), Cleopatra, etc., papyri of those times, whether Greek or Egyptian, are scarcely to be found.

The Roman Period.

In 3o B.C. Augustus took Egypt as the prize of conquest. He treated it as a part of his personal domain, free from any interference by the senate. In the main lines the Ptolemaic organization was preserved, but Romans were gradually introduced into the highest offices. On Egypt Rome depended for its supplies of corn; entrenched there, a revolting general would be difficult to attack, and by simply holding back the grain ships could threaten Rome with starvation. No senator, therefore, was permitted to take office or even to set foot in the country without the emperor's special leave, and by way of precaution the highest position, that of prefect, was filled by a Roman of equestrian rank only. As the representative of the emperor, this officer assumed the place occupied by the king under the old order, except that his power was limited by the right of appeal to Caesar. The first pre fect, Cornelius Gallus, tamed the natives of Upper Egypt to the new yoke by force of arms, and meeting ambassadors from Ethio pia at Philae, established a nominal protectorate of Rome over the frontier district, which had been abandoned by the later Ptolemies. The third prefect, Gaius Petronius, cleared the neglected canals for irrigation; he also repelled an invasion of the Ethiopians and pur sued them far up the Nile, finally storming the capital of Napata. But no attempt was made to hold Ethiopia and the boundary of the empire was fixed 7o miles south of the First Cataract, the limit of the Dodecaschoenus. In succeeding reigns much trouble was caused by jealousies and quarrels between the Greeks and the Jews, to whom Augustus had granted privileges as valuable as those ac corded the Greeks. Aiming at the spice trade, Aelius Gallus, the second prefect of Egypt under Augustus, had made an unsuccessful expedition to conquer Arabia Felix; the valuable Indian trade, however, was secured by Claudius for Egypt at the expense of Arabia, and the Red Sea routes were improved. Nero's reign espe cially marks the commencement of an era of prosperity which lasted about a century. Under Vespasian the Jewish temple at Leontopolis in the Delta, which Onias had founded in the reign of Ptolemy Philometor, was closed ; worse still, a great Jewish revolt and massacre of the Greeks in the reign of Trajan resulted, of ter a stubborn conflict of many months with the Roman army under Marcius Livianus Turbo, in the virtual extermination of the Jews in Alexandria and the loss of all their privileges. Hadrian, who twice visited Egypt (A.D. i30, 134), founded Antinoe in mem ory of his drowned favourite. From this reign onwards buildings in the Graeco-Roman style were erected throughout the country. A new Sothic cycle began in A.D. r39. Under Marcus Aurelius a revolt of the Bucolic or native troops recruited for home service was taken up by the whole of the native population and was sup pressed only after several years of fighting. The Bucolic war caused infinite damage to the agriculture of the country, and marks the beginning of its rapid decline under a burdensome tax ation. The province of Africa was now of equal importance with Egypt for the grain supply of the capital. Avidius Cassius, who led the Roman forces in the war, usurped the purple and was ac knowledged by the armies of Syria and Egypt. On the approach of Marcus Aurelius, the adherents of Cassius slew him, and the clemency of the emperor restored peace. After the downfall of the house of the Antonines, Pescennius Niger, who commanded the forces in Egypt, was proclaimed emperor on the death of Pertinax (A.D. 193). Severus overthrew his rival (A.D. 194) and, the revolt having been a military one, did not punish the province; in 202 he gave a constitution to Alexandria and the "nome" capi tals. In his reign the Christians of Egypt suffered the first of their many persecutions.Caracalla, in revenge for an affront, massacred all the men capable of bearing arms in Alexandria. His granting of the Roman citizenship to all Egyptians in common with the other provincials was only to extort more taxes. Under Decius (A.D. 25o) the Christians again suffered from persecution. When the empire broke up in the weak reign of Gallienus, the prefect Aemilianus, who took the surname Alexander or Alexandrinus, was made emperor by the troops at Alexandria, but was con quered by the forces of Gallienus. In his brief reign of only a few months he had driven back an invasion of the Blemmyes. This predatory tribe, issuing from Nubia, was long to be the terror of Upper Egypt. Zenobia, queen of Palmyra, after an unsuccessful invasion, on a second attempt conquered Egypt, which she added to her empire, but lost it when Aurelian made war upon her (A.D. 272). The province was, however, unsettled, and the conquest of Palmyra was followed in the same year by the suppression of a revolt in Egypt (A.D. 273). Probus, who had governed Egypt for Aurelian and Tacitus, was subsequently chosen by the troops to succeed Tacitus, and is the first governor of this province who obtained the whole of the empire. He expelled the Blemmyes, who were dominating the whole of the Thebaid. Diocletian invited the Nobatae to settle in the Dodecaschoenus as a barrier against their incursions, and subsidized both Blemmyes and Nobatae. The country, however, was still disturbed, and in A.D. 296 a for midable revolt broke out, led by Achilleus, who as emperor took the name Domitius Domitianus. Diocletian, finding his troops unable to determine the struggle, came to Egypt, captured Alex andria, and put his rival to death (296). He then reorganized the whole province, and the well-known "Pompey's Pillar" was set up by the grateful and repentant Alexandrians to commemorate his gift to them of part of the corn tribute.

The Coptic era of Diocletian or of the Martyrs dates from the accession of Diocletian (A.D. 284). The edict of A.D. 3o3 against the Christians, and those which succeeded it, were rigorously car ried out in Egypt, where Paganism was still strong and face to face with a strong and united church. Galerius, who succeeded Diocletian in the government of the East, implacably pursued his policy, and this great persecution did not end until the perse cutor, perishing, it is said, of the dire malady of Herod and Philip II. of Spain, sent out an edict of toleration (A.D. 311).

At the Council of Nicaea the most conspicuous controversialist on the Orthodox side was the young Alexandrian deacon Athana sius, who returned home to be made archbishop of Alexandria (A.D. 326). After being four times expelled by the Arians and once by the Emperor Julian, he died A.D. 373, at the moment when an Arian persecution began. So large a proportion of the popula tion had taken religious vows that under Valens it became neces sary to abolish the privilege of monks which exempted them from military service. The reign of Theodosius I. witnessed the over throw of Arianism, and this was followed by the suppression of Paganism, against which a final edict was promulgated A.D. 39o. In Egypt, the year before, the temple of Serapis at Alexandria had been captured after much bloodshed by the Christian mob and turned into a church. Cyril, the patriarch of Alexandria (A.D. 415) , expelled the Jews from the capital with the aid of the mob, and murdered the beautiful philosopher Hypatia. A schism now produced lengthened civil war and alienated Egypt from the em pire. The distinction between religion and politics seemed to be lost, and the government grew weaker and weaker. The system of local government by citizens had entirely disappeared. Of fices, with new Byzantine names, were now almost hereditary in the wealthy land-owning families. The Greek rulers of the Or thodox faith were unable to protect the tillers of the soil, and these being of the Monophysite persuasion and having their own church and patriarch, hated the Orthodox patriarch (who from the time of Justinian onwards was identical with the prefect) and all his following. Towards the middle of the 5th century, the Blemmyes, quiet since the reign of Diocletian, recommenced their incursions, and were even joined in them by the Nobatae. These tribes were twice brought to account severely for their misdoings, but were not effectually checked. It was in these circumstances that Egypt fell without conflict when attacked by Chosroes (A.D. 616) . After ten years of Persian dominion the success of Her aclius restored Egypt to the empire, and for a time it again re ceived a Greek governor. The Monophysites, who had taken advantage of the Persian occupation, were persecuted and their patriarch expelled. The Arab conquest was welcomed by the na tive Christians, but with it they ceased to be the Egyptian nation.

The decline of Egypt was due to the purely military govern ment of the Romans, and their subsequent alliance with the Greek party of Alexandria, which never represented the country. Under weak emperors, the rest of Egypt was exposed to the inroads of savages, and left to fall into a condition of barbarism. Eccle siastical disputes tended to alienate both the native population and the Alexandrians. Thus at last the country was merely held by force, and the authority of the governor was little recognized be yond the capital, except where garrisons were stationed. There was no military spirit in a population unused to arms, nor any disinclination to be relieved from an arbitrary and persecuting rule. Thus the Muslim conquest was easy.