Egyptian Architecture

EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE. The architecture of an cient Egypt is a primary contribution to world architecture. Its methods of construction were so essentially simple and its ma terial for monumental work so imperishable, that its survival is unique. The modern designer has much to learn from the severity and grandeur of its masses, its treatments of broad planes and the sculpturesque qualities of its highest manifestations. Some of its monumental work was rock-cut, but most of it was built with enormous masses of stone or granite, set with the utmost nicety and care and worked to the finest possible surface. Egyp tian architecture was perfectly suited to its natural environment —the sandy desert adjacent to the Nile. It was of the simplest possible form : the arch or vault was not used, except with crude brick, in subsidiary positions and constructed in a manner that produced the minimum of risk. It is clear, however, that the principle of the true arch was understood. There is no other instance in the world's history of a prevailing type of structure persisting, comparatively unchanged, for such a long period of time. Emerging, probably from the East, over 3,00o years be fore our era, its principal forms have stamped themselves in delibly on the consciousness of mankind. Even the dominance of Rome failed to make any permanent impression; and it was only when Rome ceased to exploit a province that had no po litical significance that these forms became extinct.

Pyramids and Mastabas.

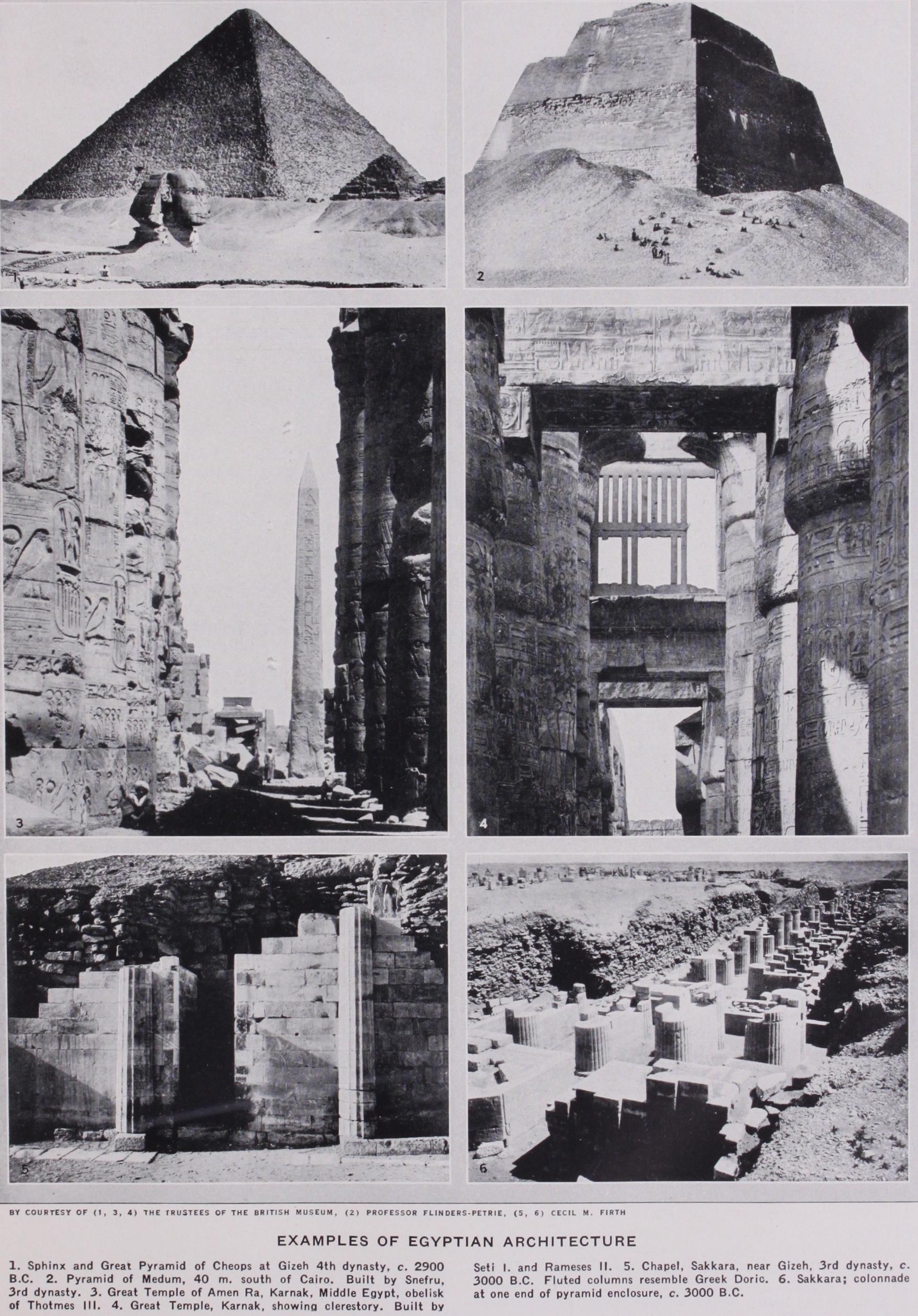

The vast superstructures which the early kings erected to enclose their tombs are characteris tically Egyptian. Though they belong more to engineering than architecture, there is no doubt about the impressiveness and grandeur of the largest examples. In the stepped pyramid of Medum, the result is truly architectonic. The slopes are so steep that they nearly resemble walls and have real monumental qual ity. At Sakkara, near Cairo, the oldest or stepped pyramid has a resemblance to the ziggurat form of Mesopotamia. Both forms though representing different ideals, are believed to be attempts to make mountains rise from plains. 'The lower stage of the Medum pyramid is finished and the intention may have been one unbroken square cone. It is probable that the Sakkara pyra '(W. R. Lethaby, quoting from Zeus, vol. iii., by A. B. Cook, in the Builder magazine, for April 6, 1928.) mid is unfinished and that the steps represent under-construction. It is clear that the pyramids at Ghizeh were finished with smooth limestone casing, which exists in places. The pure conical form is evident now from a distance, though the existing surfaces, for the most part, consist of rough steps of large size. The various passages and chambers in the interior of the great pyramid show amazing skill and ability in the handling of material. There is no parallel to work of this magnitude and finish at such an early age. Taking the most conservative estimate, it can hardly be later than 2900 B.C. The pyramids were, for the most part, the tombs of the kings of the fourth dynasty. Mastabas were built structures of rectangular form with sloping walls containing tomb chambers. Their lowness prevents them from being really im pressive, but the mastaba is the earlier form for those of royal or noble rank. The stepped pyramid may be a succession of mastabas, one on the top of the other. The mastabas in the great cemeteries of Sakkara are important because of their internal decoration.

Rock-cut Tombs and Monuments.

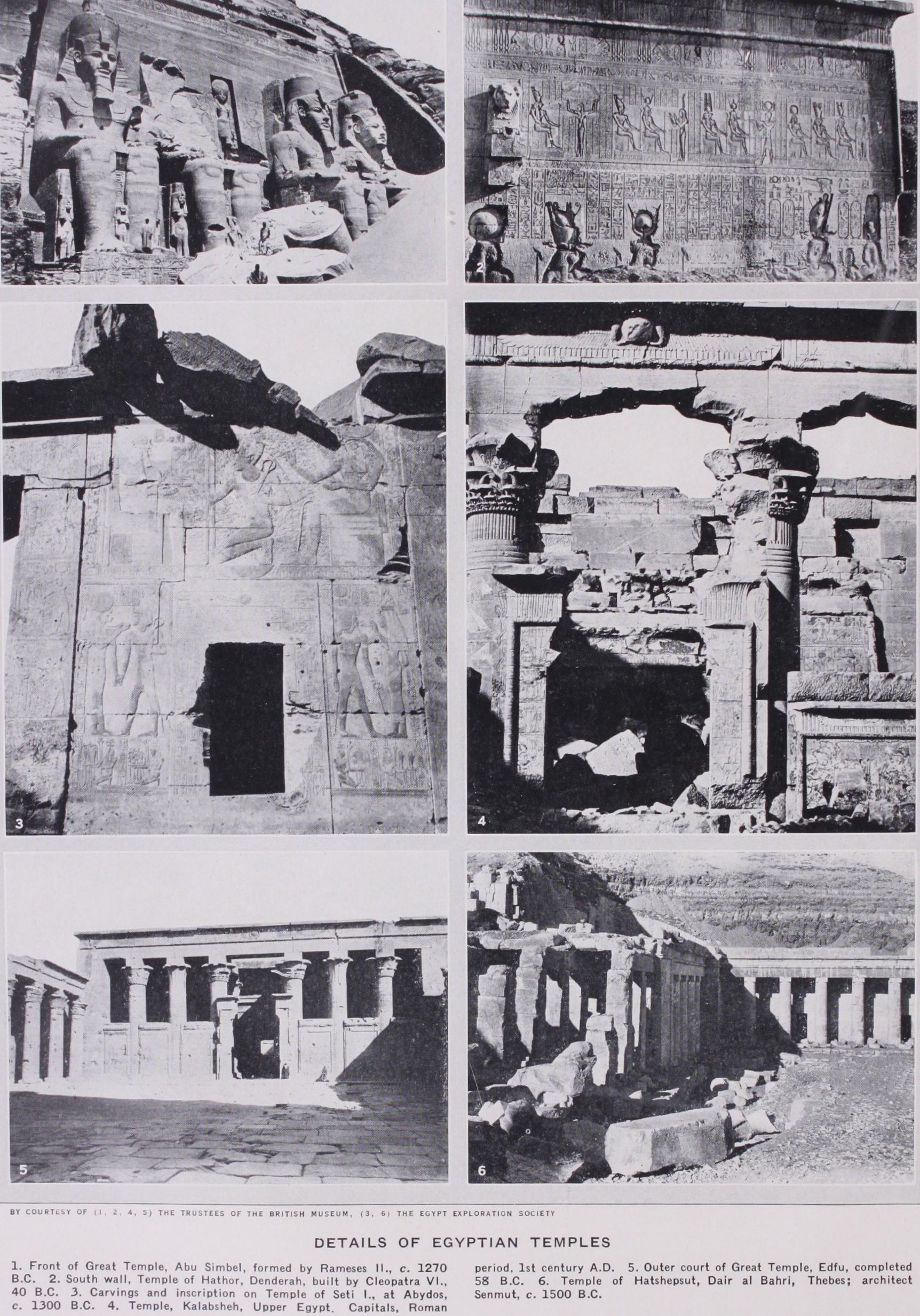

In some rock-cut tombs of the 12th dynasty (c. 2000 B.c.) at Beni-Hassan, in Middle Egypt, pillars are finely used and some of the ceilings are curved. One of these tombs has a front with a strong resemblance—though on the surface only—to Greek Doric work of some 1,500 years later. The grandest expression of rock-cut treatment is that of the two 19th dynasty temples at Abu Simbel in Nubia, on the Upper Nile, which are both works of Rameses II., one of the greatest builders of all time. In the great temple the front is a sloping plane of sandstone rock relieved by four giant seated figures, 70 ft. high, as guardians, deeply cut out of the rock against a background which is nearly vertical. In the smaller temple, the natural slope, worked to a true surface, forms the front and the figures are deeply incised, forming long panels. The 18th dynasty temple of Queen Hatshepsut, at Deir-el-Bahari, Thebes, is also rock-cut, as the natural rock, rising to a great height out of the des ert, forms a background to a long built front of piers carrying a continuous lintel treated with the utmost simplicity. As a result, the architectural forms carry weight and seem part of the cliff face behind them : any ornament would have destroyed this effect. Complete balance is thereby secured by the great forecourt treat ments of the approach, which very successfully counteract any crushing effect from the cliff by introducing an immense base area.

Temples.

The free standing temple is the ultimate expression of Egyptian form and is, in the truest sense, monumental. A great deal is made of the approach. An avenue formed by two rows of sphinxes facing inwards—and in one case 33o yd. long—is asso ciated with an outer portal called the propylon. This feature con sists of two towers with sloping walls, connected by a smaller gateway. Beyond this is the outer court of the temple proper which is enclosed by walls or colonnades. At the temple entrance is another pylon gateway, resembling the propylon in its treatment. The temple itself is a series of halls which gradually diminish in size and height until the inner sanctuary is reached; one main axial line controls the whole. The arrangement indicated is a typical one based on several examples of the i8th and i9th dy nasties at Karnak, in Middle Egypt. The grandest part of this complete arrangement was its first or "hypostyle" hall, containing a forest of columns cut through by a central avenue of large col umns on the main axis. The hypostyle hall of the great i9th dynasty temple at Karnak is one of the architectural achievements of the world. Substantial fragments of it remain but as all its roofing slabs have gone it is difficult to realize its true effect. Of tremendous scale, containing 134 columns, its internal dimensions are 329 ft. by 170 ft., while the columns of its central avenue are 7o ft. high. We have more complete knowledge about the lighting of this hall than we have about the lighting of any Greek temple. The extra height of the central avenue enabled a clerestory, or vertical arrangement of top lighting, to be formed. This con sisted of large rectangular openings filled with pierced stone trel lises, raised above the normal roof level. We see here distinct prototypes of the Roman basilicas and of the mediaeval cathedral churches which followed on from them.The great temple at Edfu—which, though of "Ptolemaic" or Graeco-Roman times, contains all the unchanging elements of Egyptian architectural form—is very well preserved. The dignity of unbroken wall surface built to a slight slope and of immense mass in association with pylons in almost perfect preservation, can be seen there to perfection. The effect of the whole is rendered much more impressive by the all-over decoration of incised figures arranged in tiers. Taken as a whole, perhaps the most impressive building in Egypt at the present day is the i9th dynasty temple of Seti I. at Abydos, which is of peculiar plan, as its arrangement was dependent on nine shrines placed in a row, one of them dedicated to Seti himself. It is in a remarkable state of preservation and an adequate idea can be formed of the value of rooms of great size containing their ceilings, doorways and decorative treatments, almost intact. No building illustrates more clearly what Egyptian architectural form really meant in these comparatively simple elements of expression. It is a lesson in the use of form and in the richness that can be obtained by an all over method of decorating with delicate relief and colour con trolled by simple lines. These facts should give it peculiar value to modern designers and decorators. The Ptolemaic temple of Hathor at Denderah, though coarse in detail, is also a valuable example because of its completeness. This building practically exists now as it was built, so that the effect of a stone flat-roofed structure can be realized both externally and internally.

Columns, Pillars, Obelisks and Domestic Work.—Columns and pillars have an important function in all early styles and Egyptian architecture is no exception. The character of the Egyptian column was distinctive and peculiar in most of its many forms, persisting for some 3,00o years. It usually suggests natural growth, as a grouped collection of budding or flowering stalks, bound together at the base and near the top of the shaft; and it is decorated to enforce this suggestion. Circular columns discovered recently at Sakkara, by Firth, show a remarkable approximation to pure Greek Doric ones of the fifth century B.C. ; and as the Egyptian ones are ascribed to the third dynasty and must have been executed about 300o B.C., they are of great significance in the history of art. The pillar is essentially a square and not a round support. Plain square pillars can be seen in the "granite temple" at Ghizeh but many-sided ones, cut out of square, are more usual. This principle is sometimes carried so far that the effect of circular columns is obtained, as in the tomb at Beni Hassan, already cited. Some pillars at the temple of Seti I., Abydos, have shallow flutings, with a plain inscribed strip on each of the four cardinal faces. Egyptian pillars are more suggestive of Indian forms than of the Aegean or Greek ones. They often have fine sculpturesque quality and could be used appropriately in the concrete constructions of to-day.

The obelisk is an Egyptian form of commemorative pillar which survived into Renaissance and modern times. It is akin to the inscribed pillars of the Sumerians in Chaldea and had, prob ably, some special religious significance. It is peculiarly suited to its surroundings as used in Egypt and has great monumental value in certain positions. The earliest examples date from the II th dynasty. Senmut used obelisks in the temple at Deir el Bahari.

Domestic buildings have, of course, completely but we know from painted representations that some of them were treated with great delicacy and fine decorative quality, sug gestive of a kind of pole and curtain construction. There is a slight but graceful cornice of the prevailing type and, obviously, a flat roof. This form of structure may well have influenced Pompeian decoration.

is customary to regard Egyptian building as destitute of any but the simplest mouldings; what is known as the "gorge"—or overhanging hollow moulding—with a plain roll member beneath it which was also carried down the external angles of the walls and doorways, being accepted as practically the only mouldings used. It is true that these, based on natural forms, were universal and were used for every kind of cornice and crowning member. Nevertheless, there is a considerable feeling of moulded form in many of the columns. Apart from mouldings the ornamental form of many of the spreading capitals is most pronounced and constitutes a definite emphasis which amounts, in places, to richness. Of other architectural enrichment there is really only one form but it is a most effective one—the winged solar disc, which was used over doorways and pylons in the hollow of the cornice.

Sculpture.

The sculpture of ancient Egypt is justly famous for its qualities of extreme simplicity and grandeur and some of the finest examples are truly architectonic. In this category are the maneless lions of red granite, now in the British Museum, belonging to the reign of Tutankhamen in the 18th dynasty. The nobility of animal form in repose has never been conveyed with greater truth and absence of superfluous detail. The seated figures at Abu Simbel are even more pronouncedly architectonic and show the same mastery. The celebrated sphinx, of doubtful date, near the pyramids of Ghizeh, is a colossal tour-de-force of sculpture, which, from its size, constitutes a monument; in a lesser degree the seated colossi of the Theban plain are in the same category. Less successful. because coarser in detail, are the pillared supports in the form of human figures in the Ramesseum at Thebes and the human-headed capitals with four faces from the Hathor columns in the temple at Denderah. The avenue of ram-headed sphinxes at Karnak is an example of emphasis by reiteration, and must have impressed those approaching the temple with a feeling of mystery and awe ; but like all other things in Egyptian sculpture, they were rendered with monumental calm.Surface Decoration.—If pronounced sculpture in the round was of considerable architectonic value, it was overshadowed in that respect by the relief sculpture and incised work which were the prevailing forms of wall decoration in all periods. To decorate walls with any completeness, there must be subject material and, like other races of the early world, the Egyptians were at no loss in this respect. With a thoroughness which has never been ex celled, they carved on their wall surfaces the intricate systems connected with their worship of the dead as well as the ceremonies and observances of their life on earth. At its best, it is neither sculpture nor painted decoration, but both of these combined. Nowhere is it seen to greater advantage than, as at Abydos, in the smooth limestone which was capable of taking the most delicate relief. In the dry climate of Egypt, parts of the painted finish seem as fresh to-day as when they were executed. The method is one of incision as well as relief in which the grades of sharpness in definition were treated with amazing skill. Even in granite this system prevailed, combined with the simpler incised work of symbols and hieroglyphics, the schematic material being grouped by means of incised lines and delicate bands. The decoration travels round doorways and enhances their value by a skillful arrangement of shallow panels emphasizing posts and lintels. Nothing could be more complete and, in its way, more successful. The Hindu decorated by serried ranks of figures in relief ; the Assyrian by delicate reliefs in fine stone or alabaster; the Greek by a restrained scheme of friezes ; but nothing at once so compre hensive and so architectonic as the finest Egyptian decoration has ever been produced. It is an all-over principle which even includes columns without interfering with their sense of structural stability.

At a certain brief period in Egyptian art—that of the ill-fated Akhenaton (Ikhnaton, q.v.) of the i8th dynasty—an extraordi nary development in painted plaster decoration occurred, which was contemporary with and doubtless influenced by somewhat similar work in late Minoan Crete. The floors of Akhenaton's palace at Tel-el-Amarna were covered with this plaster, for the most part representing Nilotic plants and birds arranged in large panels with an astonishing richness and variety of detail. See EGYPT, ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY.