Ellipse

ELLIPSE, in geometry, a closed plane curve of second de gree (order and class), or a conic section (q.v.) made by a plane cutting all elements of a circular cone, considered either as solid or as surface. It may be regarded either as the plane area enclosed or preferably as its bounding curve. In fig. 1, OVE represents the trace of a cone cut through its axis by the plane of the paper; and OV, OM, OE, etc., represent the positions of a plane, at right-angles to the plane of the paper, rotating about 0. In the position OV, the ellipse collapses into a double line OV; in the middle position OM it becomes a circle; in position OP, parallel to the opposite element VM, the section expands into a parabola; on further turning, in posi tion OH, it becomes an hyperbola. This is the view taken by Apollonius (c. 220 B.C.). Menaechmus (c. 35o B.C.) probably con ceived the ellipse as made by a plane perpendicular to OV, the cone-angle V being acute. On V's retiring to infinity (co), the cone becomes a cylinder (q.v.), but the section remains an ellipse, the parabola becoming a pair of parallel lines.

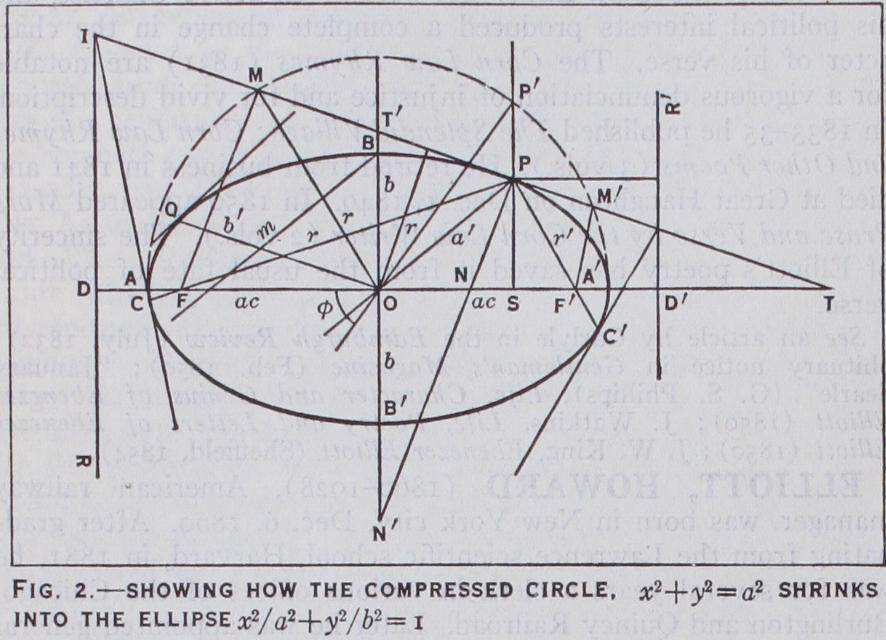

Viewed solely as a plane curve, the ellipse may be variously defined by some distinctive property. Most simply, it is the compression of a circle (called the major or auxiliary circle) by the affine transformation x=x', Suppose the a whole plane to settle toward the horizontal x-axis (fig. 2) every vertical line shrinking uniformly in the ratio b: a; then the circle shrinks into the ellipse I.

Imagine the shadow cast by a circular disc, in sunlight perpen dicular to a vertical wall, as the disc rotates round a horizontal diameter parallel to the wall. In the shadow the vertical chords are all shortened, being multiplied by sin° (the slope of the disc to the light-rays). It is seen instantly that the circle-area is reduced in the same ratio b/a and becomes crab for the ellipse, and that any tangent to the circle becomes a tangent to the ellipse, merely rotating about its intersection T with the axis.

The central vertical BB' is called the minor axis, and the circle about it as diameter is called the minor circle. The circle of radius a about B as centre cuts the major axis AA° at F and F', points of special importance (called foci) ; / If we call this ae, we have e= -\/ (i — b , I —0= ; e is the eccentricity, and ae the linear eccentricity. If P' and P be any two corresponding points on the major circle and the ellipse, and S the common foot of the ordinates P'S, PS, then the angle SOP' is termed the eccentric angle e of P. Then (a2-x2) _ and r'=a-ex.

Similarly, FP=r=a--ex; hence r+-r'=2a; i.e., the sum of the distances of any point (P) of an ellipse from two fixed points (F, F') is a constant (the major axis, 2a). This is the ordinary definition of an ellipse. If we think of F' as a pole; then its polar (the locus of the intersection I of tangents at the ends of a chord C'F'C) will be I, or x= a/ e, the vertical D'R' (directrix) ; with the points F' and D' in involution, OF'. OD' = = Hence the distance d, of any point P of the ellipse from D'R', is a/e — x, which is equal to r/e; or e = r/d; i.e., the ratio of the distances of any point of the ellipse from a focus (F') and the directrix is a constant, the eccen tricity (< I), which gives the preferred definition of an ellipse.

Conjugate diameters in the circle each bisecting all chords parallel to the other, do not remain mutually perpendicular in an ellipse, being pressed down towards the axis AA'; but they still bisect as in the circle, since all parallel lengths are shortened throughout in the same ratio, varying with the direction of the chord. Hence the equation of the ellipse referred to conjugate diameters 2a', 2b' as co-ordinate axes is It is easily shown that = a constant. Again, if 4) be the angle between two conjugates, then sin4=ab/a'b', or 4a'b' sin cf)= 4ab; i.e., the parallelogram of tangents at the ends of con jugate diameters is constant in area.

The tangent and normal at any point P bisect the angles be tween the focal radii FP, F'P; hence any ray from F is reflected at P through F' and then back to F, and all rays from either focus converge in reflection, on the other; a fact of significance in the study of light, sound, etc. Any perpendicular from a focus on a tangent meets it on the major circle; the product of two such per pendiculars (from F, F') is a constant. From any outside point Q two tangents QT, QT' may be drawn to E; then the angles of these tangents with focal radii to Q will be equal; i.e., L TQF= L T'QF'. If L TQT' be a right angle, then Q is on the director circle This follows at once from the equation of the tangent, y = . To obtain the equation of the perpendicular tangent, change m into — I/m, then eliminate m. Various simple relations connect the subtangents and subnormals.

The area of an ellipse is crab. To find the arc-length involves the use of elliptic integrals and their Abelian inverses, elliptic functions, and doubly periodic functions in general (see ELLIPTIC FUNCTIONS.) Kepler's approximation it (a+b) is about too large, and 7r y is about as much too small ; their mean errs by about 1 3000• Construction and Analysis.—An ellipse may be drawn by fastening the ends of a cord units in length at F and F', and then passing a pencil point along the cord held taut by the point (all in the same plane). Alternatively any number of points may be found as follows : Draw concentric major and minor circles (radii a and b) about 0; and any radius cutting them at P and Q. Through P draw the vertical chord VV', and through Q the horizontal chord HH'; these meet in a point M on the ellipse, for the x of V on the circle is unchanged, and y is shortened in ratio b/a.

To find the axes of an ellipse, bisect two pairs of parallel chords; the bisectors will be diameters meeting in the centre 0. About 0 draw any circle cutting the ellipse in four points ; these are obviously symmetrical with respect to the axes, which are the mid-parallels to the sides of their rectangle. The foci are F and F' on the major axis AA' (2a) , each at a distance of a from the ends B, B' of the minor axis. The directrices are parallel to BB', and each is distant d = a/e = =the intercept between the axes on a parallel to BF, through A. The ellipse is con spicuous in astronomy as the path of a single mass-centre about another obeying the Newtonian law of inverse squares. The attraction of other planets perturbs this path of any one planet round the central sun. (See also PROJECTIVE GEOMETRY.) (W. B. SM.)