Ellipsographs

ELLIPSOGRAPHS. The earliest method of drawing ellipses is by means of a stretched string, a device still adopted by garden ers and others in setting out large ellipses. It is based on the property of the ellipse that if P is any point on the curve and F,F' are the two foci, then PF-+-PF' is of constant value, equal to the length AA' of the ellipse. The positions of F and F' on the major axis AA' of the ellipse are found by setting off BF and BF' each equal to half the length of the ellipse. The ends of a piece of string are secured at F and F' in such a way that the length of the free portion FPF' is equal to that of the ellipse. A pencil or other marking point P pressed outwards against the string, if moved so as to keep the string always taut, will draw the re quired ellipse. Though quite sat isfactory for such work as setting out the shape of an elliptical flower-bed, the difficulty due to variable stretching of the string renders it unsuitable for accurate work. Various simple arrange ments for facilitating the application of this method to the draw ing of small ellipses have, however, been devised by W. F. Stanley, H. V. Hazard (1884), V. E. Contonze (1895), Professor Honey, R. Ramm and others.

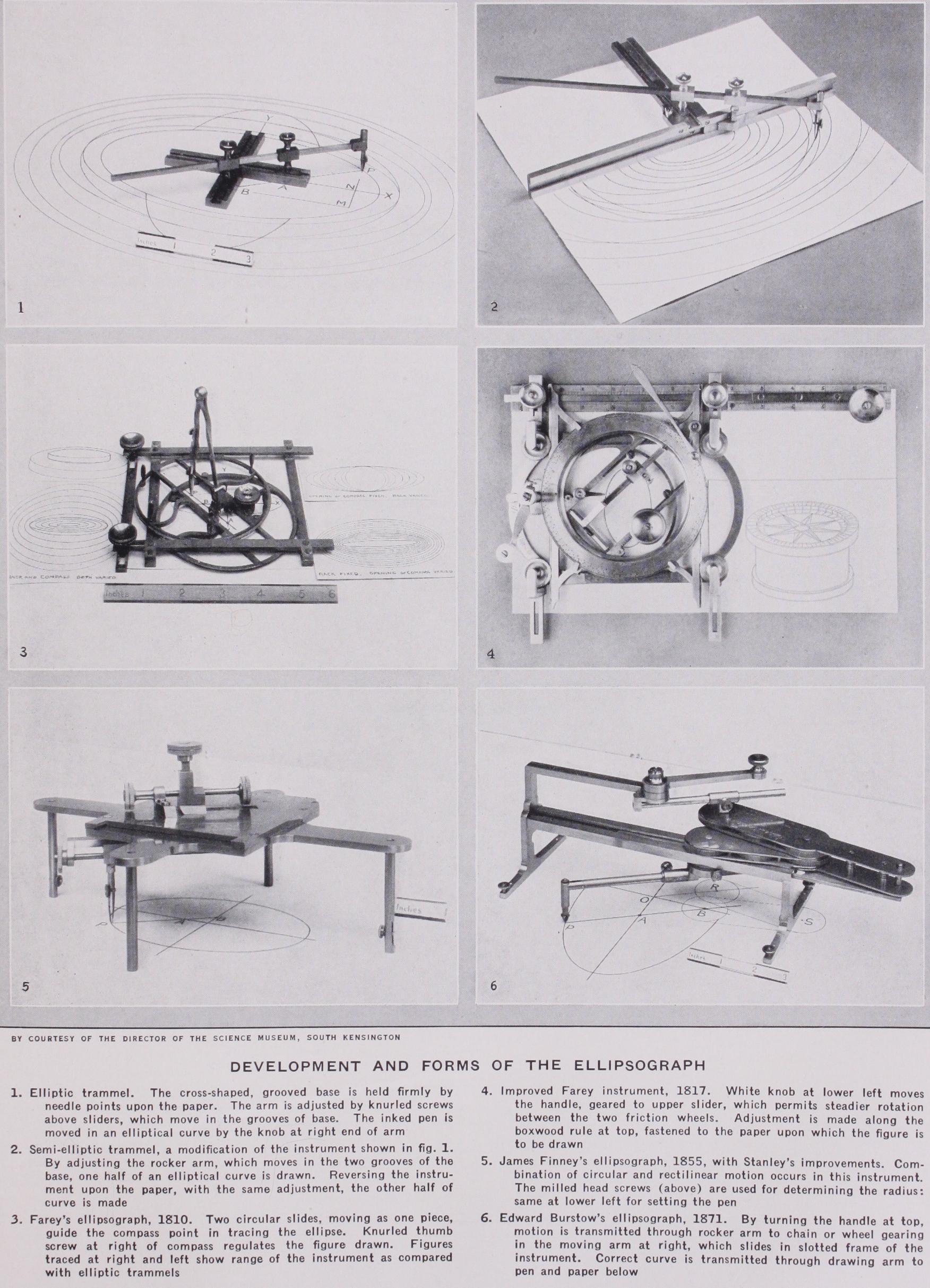

The most simple and most widely used instruments for drawing ellipses such as are required in ordinary drawing office practice is the elliptic trammel. When two points A, B, a fixed distance apart, are constrained to move along two mutually perpendicular straight lines XX,YY, any point P in the line AB, or in that line produced, describes an ellipse. On this principle the elliptic trammel provides a convenient means of describing ellipses of various sizes and proportions. In the example shown in Plate I., fig. I, a cross-shaped piece of metal has two undercut grooves at right angles to each other, and is fixed to the paper by needle points underneath. Two sliders fitting in the grooves carry heads, through which passes a bar to which each head can be clamped. The describing pen or pencil is attached to the end of the bar.

Ellipses of a width less than the length of each groove cannot be drawn.

In the semi-elliptic trammel this difficulty is overcome to a certain extent by cutting away one arm of the cross. If a com plete ellipse is required, the two halves of the curve must be drawn separately. An example is shown in Plate I., fig. 2. The long groove is in a plane below the short groove, and along the front of the instrument ; the slides can therefore be made long so as to ensure steady working.

For drawing ellipses of small size, John Farey in 1810 devised his modification of the ordinary trammel, since known as Farey's ellipsograph. Plate I., fig. 3 shows the original instrument made by him and given in 1812 to the Society of Arts, who awarded him a gold medal for the invention. The grooves of the ordinary trammel are replaced by two pairs of parallel bars fixed at right angles to each other. Each of the two slides takes the form of a circular ring about 4 inches in diameter, and the distance between the centres of the rings can be varied from zero to about 1.2 inches by means of a small rack and pinion with milled head. This is the only relative motion possible between the two circles, which move as one rigid piece when an ellipse is being drawn. Attached to the upper circle is a swivel socket, in which the end of one arm of an ordinary pair of bow compasses may be fixed; this affords an easy and quick means of adjusting the position of the drawing point. Clamped to the frame by two milled-headed screws is a ruler having two needle points projecting from its under surface ; this ruler being placed approximately in position, the frame can be adjusted exactly to the right position for drawing the required ellipse. The action of the instrument may be under stood by consideration of the equivalent trammel shown drawn underneath the instrument in the illustration.

Farey improved the original form of the instrument by the addition of various adjustments. The example shown in Plate I., fig. 4, which was made in 1817, contains the following improve ments. Steadier rotation of the instrument is secured by means of a handle and small pinion gearing with a toothed wheel attached to the upper slider, which slides between two pairs of friction wheels. For drawing ellipses whose major axes are parallel, the instrument is attached to a brass plate which, by means of rack and pinion, can slide along a groove in a boxwood rule 14in. long. This rule is divided into inches and twentieths, and is kept fixed to the paper by three projecting needle-points underneath. Instead of the ordinary pair of compasses for varying the radius, an arm is provided carrying a rack-and-pinion adjustment for the pen.

Another important addition, first introduced by Farey in 1813, is a dividing plate for facilitating such work as the drawing of orthogonal projections of the divisions on divided circles, in drawings such as that shown with the instrument. The dividing plate on this instrument is provided with five sets of holes, giving 36o, 96, 90, 72 and 6o divisions to the complete circle.

With such instruments ellipses were often drawn by a diamond point direct on copper plates, and the high standard of perform ances of the instrument is indicated by the excellence of the engravings of mathematical instruments, etc., made by Farey and others, which form illustrations to scientific papers of that period. Other designers of efficient ellipsographs about this time were W. Cubitt (1817) and Joseph Clement (1818).

In another type of ellipsograph, the combination of a circular with a rectilinear motion forms the basis of the design. In the ordinary trammel, during the operation of drawing an ellipse, the point C, midway between A and B, describes a circle round 0 as centre, and the angle COA is always equal to the angle