England

ENGLAND. Geographical usage confines the name to the southern part of the island of Great Britain, excluding its western peninsula of Wales. It is the largest, wealthiest and most populous of the units within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

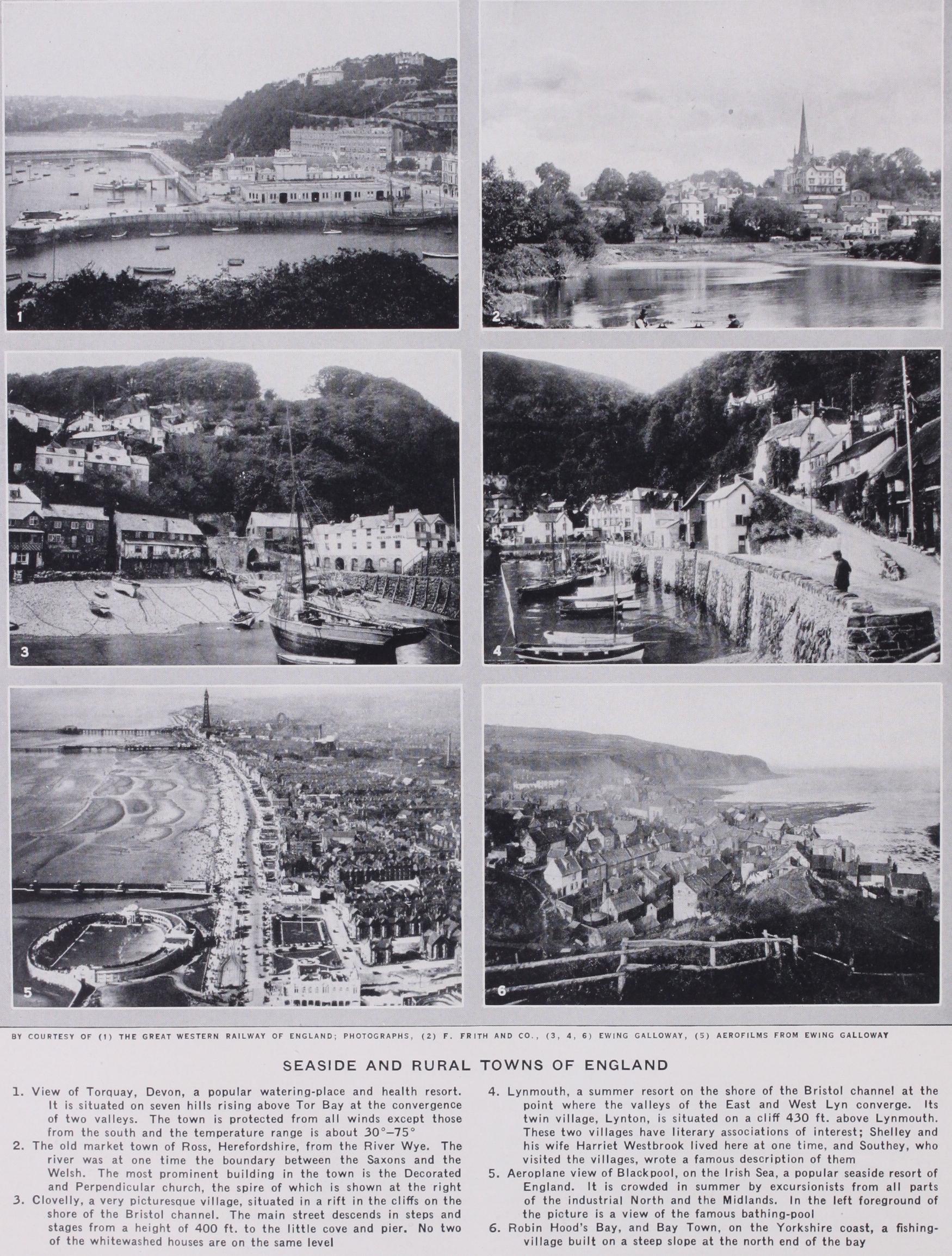

England extends from the mouth of the Tweed in 55° 46' N. to Lizard Point in 57' 30" N., in a roughly triangular form. The base of the triangle runs from the South Foreland to Land's End west by south, a distance of 316 m. in a straight line, but 545 m. following the larger curves of the coast. The east coast runs north-north-west from the South Foreland to Berwick, a distance of 348 m., or, following the coast, 64o m. The west coast runs north-north-east from Land's End to the head of Solway Firth, a distance of 354 m., or following the much-indented coast, 1,225 m. The total length of the coast-line may be put down as ap proximately 2,350 m., out of which 515 m. belong to the western principality of Wales. The most easterly point is at Lowestoft, r° 46' E., the most westerly is Land's End, in 43' W. The coasts are nowhere washed directly by the ocean, except in the extreme south-west ; the south coast faces the English Channel, which is bounded on the southern side by the coast of France, the two shores converging from 10o u. apart at the Lizard to at Dover. 'The east coast faces the shallow North sea, which widens from the point where it joins the Channel to 375 m. off the mouth of the Tweed, the opposite shores being occupied in succession by France, Belgium, Holland, Germany and Denmark. The west coast faces the Irish sea and St. George's Channel, with a width varying from 45 to 13o m.

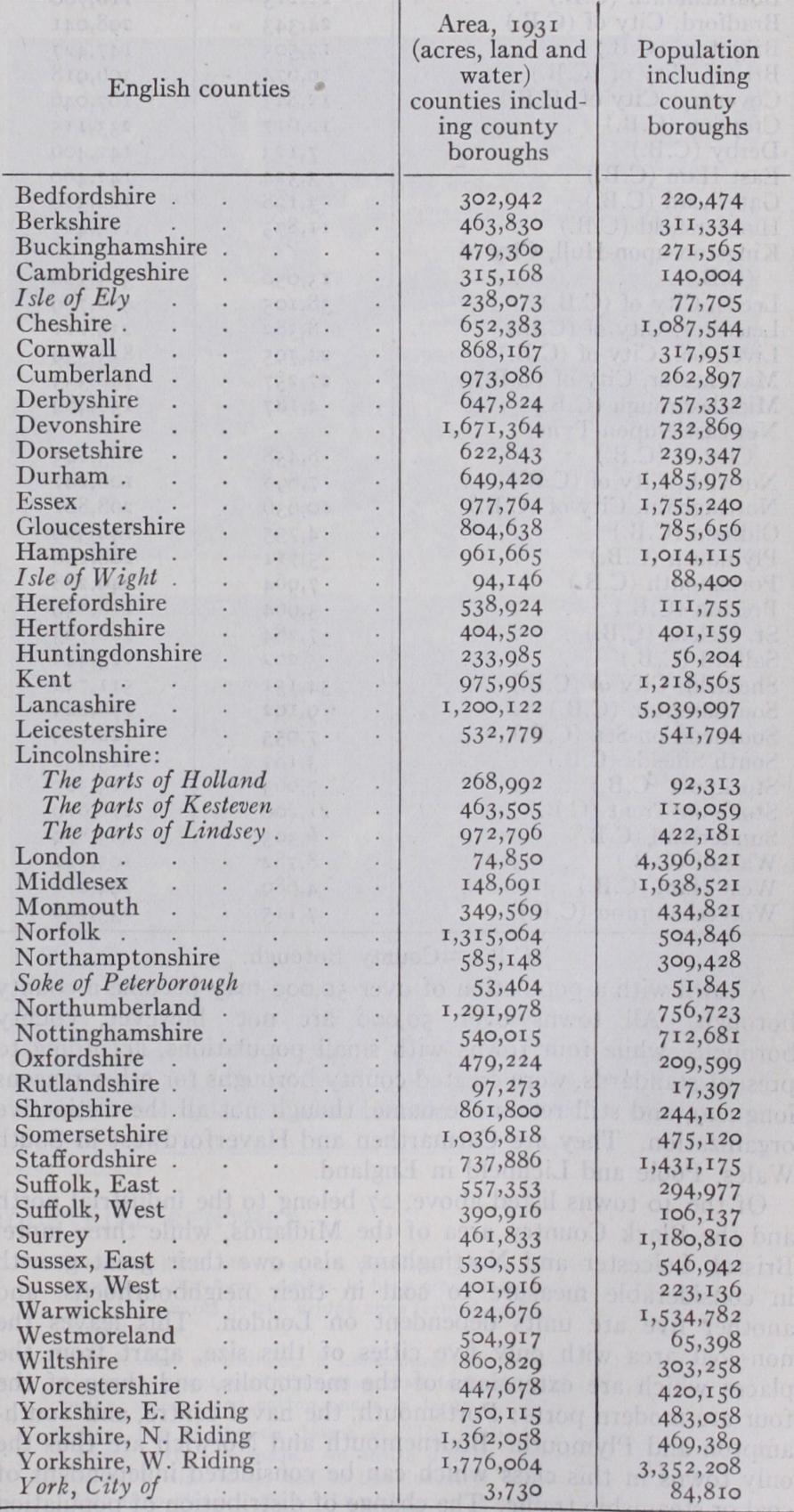

The area of England and Wales is 37,327,479ac. or 58,324 sq.m. (England, 50.851 sq.m.). The principal territorial divisions of England, as of Wales, Scotland and Ireland, are the counties (see below), of which England comprises 40. Their boundaries are not always determined by the physical features of the land; but localities are habitually defined by the use of their names.

Physical Geography.

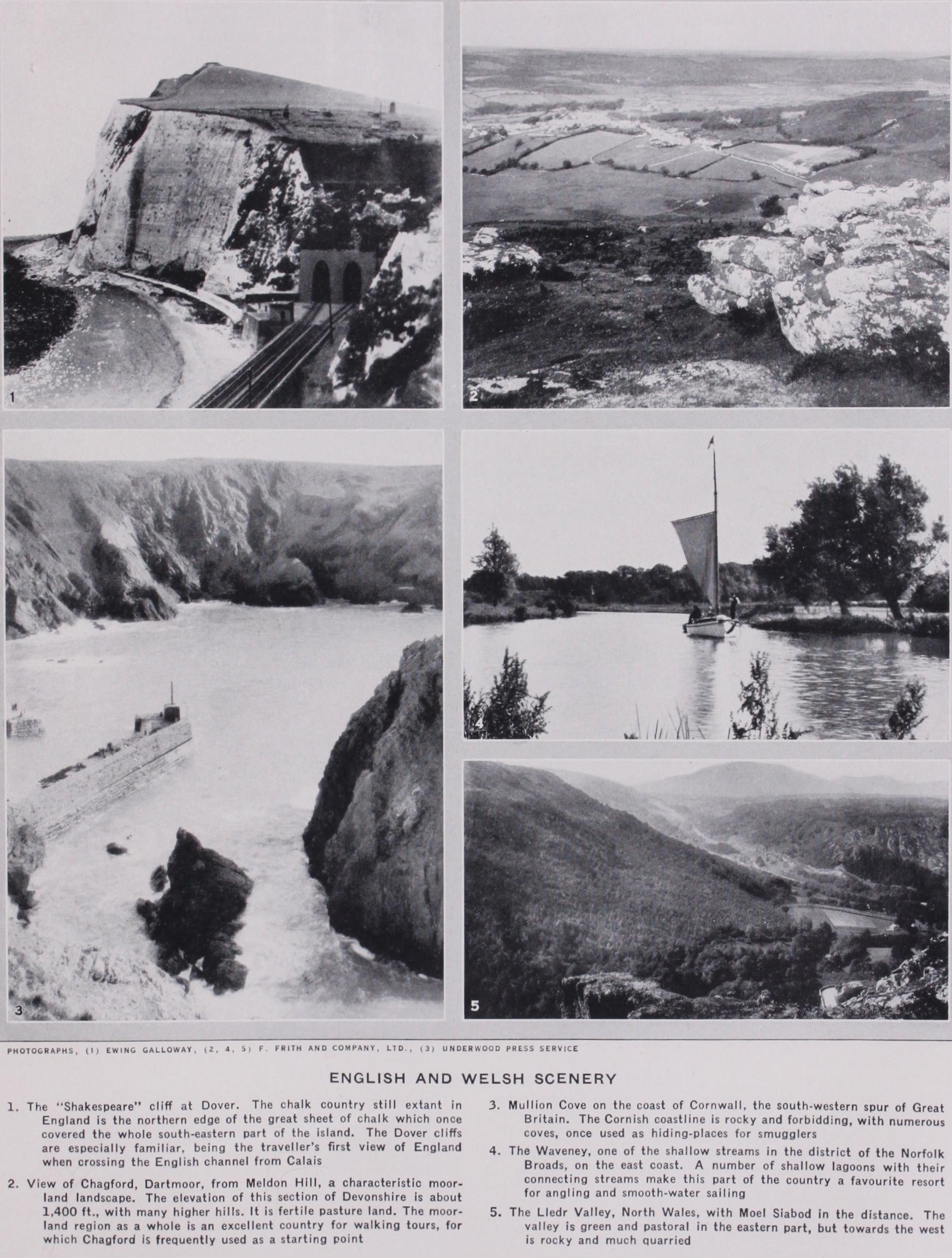

The land is highest in the west and north, where the rocks also are oldest, most disturbed, and hard est, and the land surface gradually sinks towards the east and south, where the rocks become successively less disturbed, more recent and softer. The study of orographical and geological maps of the country allows a broad distinction to be drawn between the west and east. The contrasted districts are separated by an inter mediate area, which softens the transition between them, and may be described separately.The Western Area is composed of Archaean and Palaeozoic rocks, embracing the whole range from pre-Cambrian up to Car boniferous. The outcrops of these rocks succeed each other in order of age in roughly concentric belts, with the Archaean mass of the island of Anglesey as a centre, but the arrangement in detail is much disturbed and often very irregular. Contemporary igneous outbursts are important in some of the ancient forma tions, and add, by their resistance to atmospheric erosion, to the ruggedness of the scenery (see CARNARvoNsHIRE). The hills and uplands of ancient rocks do not always form regular ranges, but often rise like islands in distinct groups from a plain of New Red Sandstone (Permian and Triassic), which separates them from each other and from the newer rocks of the Eastern Area. Each of the uplands is a centre for the dispersal of streams that flow rapidly to the sea.

The Eastern Area, lying to the east of the zone of New Red Sandstone, is defined on the west by a slightly curved line drawn from the estuary of the Tees through Leicester and Stratford-on Avon to the estuary of the Severn, and thence through Glaston bury to Sidmouth. It is built up of nearly uniform sheets of Meso zoic rock, the various beds of the Jurassic lying above the New Red Sandstone (Triassic), and dipping south-eastward under the successive beds of the Cretaceous system. In exactly the same way the whole of the south-east of the island appears to have been covered uniformly with gently dipping beds of early Tertiary sands and clays, beneath which the Cretaceous strata dipped. At some period subsequent to this deposition there was a movement of elevation, which appears to have thrown the whole mass of rocks into a fold along an anticlinal axis running west and east, which was flanked to north and south by synclinal hollows. In these hollows the early Tertiary rocks were protected from ero sion, and remain to form the London and the Hampshire Basins respectively, while on the anticlinal axis the whole of the early Tertiary and the upper Cretaceous strata have been dissected away, giving the complex configuration of the Weald. The general character of the landscape in the Eastern Area is a succession of steep escarpments formed by the edges of the outcropping beds of harder rock, and long gentle slopes or plains on the dip-slopes, or on the softer layers; clay and hard rock alternating through out the series.

The structural contrasts between the Western and the Eastern Areas are masked in many places by deposits of boulder clay, covering most of the low ground north of the Thames basin.

The history of the origin of the land-forms of England is ex ceedingly complicated. Every geological formation (except the Miocene) is represented, suggesting a long and complicated past. Geologically the separation of Ireland was a comparatively recent episode, while the severance of the land-connection between Eng land and the continent by the formation of the Strait of Dover is still more recent and within the human period.

The Western Area:

The four groups of high land rising out of the plain of red rocks are : (a) The Lake district, bounded by the Solway Firth, More cambe bay and the valleys of the Eden and the Lund.(b) The Pennine region, which stretches from the Scottish border to the centre of England running south.

(c) Wales (q.v.), forming the western landward boundary of England.

(d) The South-western peninsula, comprising mainly the coun ties of Devon and Cornwall.

They are all similar in the great features of their land-forms, which have been impressed upon them by the prolonged action of atmospheric denudation rather than by the original order and arrangement of the rocks; but each group has its own geological character, which has imparted something of a distinctive indi viduality to the scenery. Taken as a whole, the Western Area depends for its prosperity on mineral products and manufactures rather than on farming; and the staple of the farmers is live-stock rather than agriculture.

Lake District.—The Lake District occupies the counties of Cum berland, Westmorland and north Lancashire. It forms a roughly circular highland area, the drainage lines of which radiate outward from the centre in a series of narrow valleys, the upper parts of which cut deeply into the mountains, and the lower widen into the surrounding plain. Many of the valleys have long narrow lake basins such as Windermere and Coniston, draining south; Wast water, draining south-west, Ennerdale water, Buttermere and Crummock water (the two latter, originally one lake, are now divided by a lateral delta), draining north-west; Derwent water and Bassenthwaite water (which were probably originally one lake), and Thirlmere, draining north; Ullswater and Haweswater, draining north-east. There are, besides, numerous mountain tarns of small size, most of them in hollows barred by the glacial drift which covers a great part of the district. The central and most picturesque part of the district is formed of great masses of volcanic ashes and tuffs, with intrusions of basalts and granite, all of Ordovician (Lower Silurian) age. Scafell and Scafell Pike (3,162 and 3,210 ft.), at the head of Wastwater, and Helvellyn (3,118), at the head of Ullswater, are of great grandeur in spite of their moderate height. Sedimentary rocks of the same age form a belt to the north, and include Skiddaw (3,054ft.); while to the south a belt of Silurian rocks, thickly covered with boulder clay, forms the finely wooded valleys of Coniston and Winder mere. Round these central masses of early Palaeozoic rocks there is a broken ring of Carboniferous limestone, and several patches of Coal Measures, while the New Red Sandstone appears as a boundary belt outside the greater part of the district, and is especially marked in the vale of Eden and the Carlisle plain, giving good agricultural land. Where the Coal Measures reach the sea at Whitehaven, there are coal-mines, and the hematite of the Carboniferous limestones has given rise to ironworks at Barrow in-Furness. Except in the towns of the outer border, the Lake district is very thinly peopled, although the remarkable beauty of its scenery attracts numerous residents and tourists. The very heavy rainfall of the district, which is the wettest in England, has led to the utilization of Thirlmere as a reservoir for the water supply of Manchester, over 8om. distant. The district is one of human contrasts, between the simple pastoral life of the high moorlands, and the richer agricultural life that centres around the "Border City," Carlisle. Both forms of life are in greater con trast to the industrial regions of the western coastland south of the district.

Pennine Region.—The Pennine region, the centre of which forms the so-called Pennine Chain, is the outstanding feature of northern England. The region is composed of Carboniferous rocks, the coal and iron deposits making the flanks of the highland busy manufacturing districts, and the centres of dense population. The whole region may be looked upon as formed by an arch or anticline of Carboniferous strata, the axis of which runs north and south ; the centre has been worn away by erosion, so that the Coal Measures have been removed, and the underlying Millstone Grit and Carboniferous limestone exposed. On both sides of the arch, east and west, the Coal Measures form outcrops which disappear towards the sea under the more recent strata of Permian or Triassic age. The northern part of the western side of the anti cline is broken off by a great fault in the valley of the Eden, and the scarp thus formed is rendered more abrupt by the presence of a sheet of intrusive basalt. In the north the Pennine region is joined to the Southern Uplands of Scotland by the Cheviot hills, a mass of granite and Old Red Sandstone ; and the norther n part is largely traversed by dykes of contemporary volcanic or in trusive rock. The most striking of these dykes is the Great Whin Sill, which crosses the country from a short distance south of Durham almost to the source of the Tees, near Crossfell. The elevated land is divided into three masses by depressions, which furnish ready means of communication between east and west. The South Tyne and Irthing valleys cut off the Cheviots on the north from the Crossfell section, which is also marked off on the south by the valleys of the Aire and Ribble from the Kinder Scout or Peak section. The numerous streams flow to the east and the south, and, by shorter and steeper valleys, to the west. The dales are separated from each other by high heather covered moorland or hill pasture. The agriculture of the region is con fined to the bottoms of the dales, and is of small importance. Crossfell (2,93oft.) and the neighbouring hills are formed from masses of Carboniferous limestone, which received its popular name of Mountain limestone from this fact. Farther south, such summits as High Seat, Whernside, Bow Fell, Penyghent and many others, all over 2,000f t. in height, are capped by portions of the grits and sandstones, which rest upon the limestone. The belt of Millstone Grit south of the Aire, lying between the great coal fields of the West Riding and Lancashire, has a lower elevation, and forms grassy uplands and dales; but farther south, the finest scenery of the whole region occurs in the limestones of Derby shire, in which the range terminates. The limestone rocks of York shire and Derbyshire show characteristic subterranean drainage. The coal-fields on the eastern side, from the Tyne nearly to the Trent, are sharply marked off on the east by the outcrop of Per mian dolomite or Magnesian limestone, which forms a low terrace dipping towards the east under more recent rocks, and in many places giving rise to an escarpment facing westward towards the gentle slope of the Pennine dales. To the west and south the Coal Measures dip gently under the New Red Sandstone, to reappear at several points through the Triassic plain. The clear water of the upland becks and the plentiful supply of water-power led to the founding of small paper-mills in remote valleys before the days of steam.

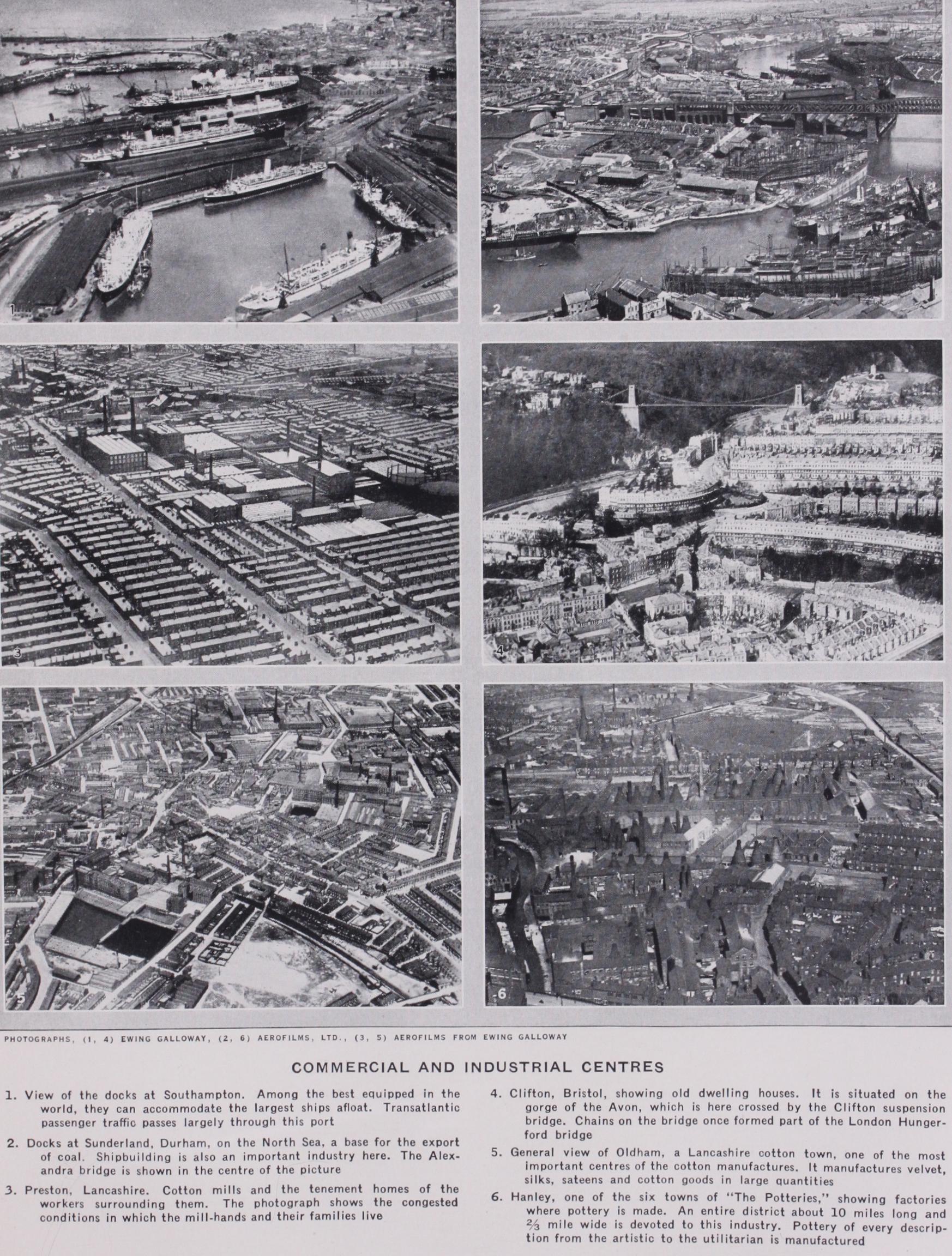

The Pennine footlands in the north-east form a very distinct geographical unit, which may be termed North-eastern England. The region is bounded on the north-west by the Cheviots, on the west by the northern Pennines and on the south-east by the North Yorkshire moors. Three important lowland gates leave the region, namely the Northallerton gate to the south, the Tyne Gap to the west and the Berwick gate to the north. The region is one of great contrast between the highly developed, congested, industrial coastal patch and the sparsely populated, bleak, sheep-rearing moorlands of the Pennines to the west. Coal has been exported from this area for centuries and the association of boatbuilding for coal-carrying has laid the foundation of the great shipbuilding industry. The use first of all of local deposits of iron ore and then of the imported raw material has made the region also a great iron-smelting area. The great industries focus around the estu aries respectively of the Tyne, Wear and Tees. Coal, chemical products and shipbuilding focus on Newcastle-on-Tyne—the re gional capital. Sunderland, the focus on the Wear, imports timber and exports coal. Difficulties in the early days with the lower Tees channel were overcome by sending the coal to Middles brough, where it met with the imported iron ores and thence arose a great iron-smelting region. The discovery of the Cleveland ores and new processes in smelting greatly improved the economic position of this region and now the iron-smelting and its asso ciated industries are world famous. The development of the heavy chemical industry based on the gypsum deposits of the Triassic is a new development. The Tees-mouth ports are grouped under Middlesbrough, Stockton and the Hartlepools. Behind the whole region lies the old-world focus of Durham, beautifully situated— the one-time capital of a vast ecclesiastical border march.

Farther south the footlands of the Pennines have long been in terested in woollen industries based upon sheep-rearing. The intro duction of cotton caused the woollen manufactures on the western side to be superseded by the working up of the imported raw ma terial; but woollen manufactures now based on imported raw ma terials have become a feature of the eastern slopes. Some quiet market-towns, such as Skipton and Keighley, remain, but most of them have developed by manufactures into great centres of popu lation, lying, as a rule, at the junction of the thickly peopled val leys, and separated from one another by the empty uplands. Such are Leeds, Bradford, Sheffield, Huddersfield and Halifax on the great and densely-peopled West Riding coal-field, which lies on the eastern slope of the Pennines. The availability of soft water, from the Millstone Grit and peat moorlands, for wool-washing is an important factor of the location of wool-towns, in the main to the north of the Calder. The traditional skill of the inhabitants has also been an important factor in the location and development of the modern woollen industry and many of the towns within the region show a high degree of specialization. Thus Bradford special izes in wool-combing and worsted work; Dewsbury in "shoddy," or the reworked material; Halifax in carpet making and heavy woollens and the Colne valley in fine clothes and tweeds. Leeds is the mercantile and engineering centre of the district with, for example, a leather industry due to its large meat markets.

High on the Pennines are Harrogate, Buxton and Matlock, health resorts, prosperous from their pure air and fine scenery.

The iron ores of the Coal Measures have given rise to great manufactures of steel. This industry has focussed on Sheffield. Familiarity with the smelting of local iron ore and the proximity of hard sandstone for grinding wheels has handed on a traditional skill in this neighbourhood also. Before the extended use of coal, the local smelting was dwindling, but cutlery manufacture revived, thanks to imported iron. With the use of coal power the produc tion of steel and its associated industries concentrated in the Don valley.

Across the moors, on the western side of the anticline, the vast and dense population of the Lancashire coal-field is crowded in the manufacturing towns surrounding the great commercial centre, Manchester, which itself stands on the edge of the Triassic plain.

Ashton, Oldham, Rochdale, Bury, Bolton and Wigan form a nearly confluent semicircle of great towns, dependent on the un derlying coal and iron and on imported cotton. The lime-free water of the region is also important for bleaching. The Lan cashire coal-field, and the portion of the bounding plain between it and the seaport of Liverpool, contain a population greater than that borne by any equal area in the country, the county of London and its surroundings not excepted. Here again the region shows concentration in certain towns of highly specialized processes. Bol ton concentrates on the spinning of fine Egyptian cotton and is im portant in the bleaching industry; Oldham deals with the medium counts, while the suburbs of Manchester deal with spinning and the city itself is the great market of the finished goods. Liverpool stands out as the great entrepxt for raw cotton and the export centre of the finished goods.

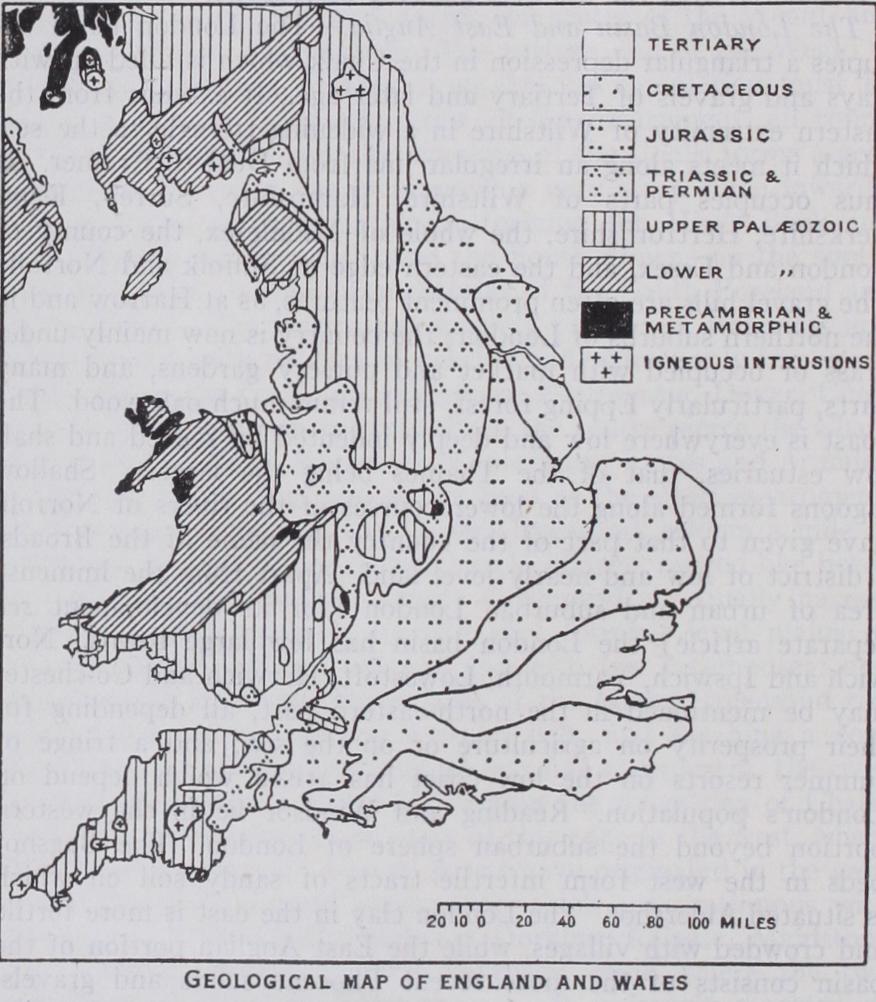

Triassic rocks form the low coastal belt of Lancashire, edged with long stretches of blown sand and dotted with pleasure towns like Blackpool and Southport.

The basin of the River Weaver is the centre of the Cheshire salt field. Modern developments tend to make this and the mid Mersey region generally the producer of heavy chemical goods— a factor of no little importance in the bleaching processes.

Chester is the seaward terminus of the way through the great Midland Gap. Like Durham on the north, it was once of greater importance than at present, as the head of a marcher lordship, in this case controlling ways into Wales and the west. The im portance of Chester in this region is that it has links with the south, the midlands and the west rather than with the north, but it has become of late a residential centre in relation to the south Lancashire cities, thanks to recent improvements of transport.

In the south-west of the Pennine region the coal-field of North Staffordshire supports the group towns known collectively from the staple of their trades as "the Potteries." The region is some what isolated industrially and is mainly dependent on the suitable carboniferous clays and marls. Six of the important pottery towns have been amalgamated into the county borough of Stoke-on Trent which with extended boundaries was raised in 1925 to the rank of a city (Pop. 1931, 276,619). Further extension of this urbanization will accentuate the already too elongated nature of the settlement. The extreme contrast between Stoke and the non-industrial, old-world town of Newcastle-under-Lyme is one that repeats itself in many parts of modern England.

The South-west.—The peninsula of Cornwall and Devon may be looked upon as formed from a synclinal trough of Devonian rocks, which appear as plateaux on the north and south, while the centre is occupied by Lower Carboniferous strata at a lower level. The northern coast, bordering the Bristol channel, is steep, with picturesque cliffs and deep bays or short valleys running into the high land, each occupied by a little seaside town or village. The plateau culminates in the barren heathy upland of Exmoor, which slopes gently southward from a general elevation of 1,60o ft., and is sparsely inhabited. The Carboniferous rocks of the centre form a soil which produces rich pasture under the heavy rainfall and mild climate, forming a great cattle-raising district. There is an interesting seasonal migration of cattle and sheep up to Bodmin Moor and Dartmoor. The Devonian strata on the south do not form such lofty elevations as those on the north, and are in consequence, like the plain of Hereford, very fertile and peculiarly adapted for fruit-growing and cider-making. The remarkable features of the scenery of south Devon and Cornwall are due to a narrow band of metamorphic rock which appears in the south of the peninsulas terminating in Lizard Head and Start Point, and to huge masses of granite and other eruptive rocks which form a series of great bosses and dykes. The largest granite boss gives relief to the wild upland of Dartmoor, cul minating in High Willhays and Yes Tor. The clay resulting from the weathering of the Dartmoor granite has formed marshes and peat Dogs. The Tamar flows from north to south on the Devonian plain, which lies between Dartmoor on the east and the similar granitic boss of Bodmin Moor (where Brown Willy rises to ft.) on the west. There are several smaller granite bosses, of which the mass of Land's End is the most important. Most of the Lizard peninsula, the only part of England stretching south of 50° N., is a mass of serpentine. The great variety of the rocks which meet the sea along the south of Cornwall and Devon has led to the formation of a singularly picturesque coast—the headlands being carved from the hardest igneous and metamorphic rocks, the bays cut back in the softer strata. The fjord-like inlets of Falmouth, Plymouth and Dartmouth are splendid natural harbours, which would have developed great commercial ports but for their remoteness from the centres of commerce and manu factures. China clay from the decomposing granites, tin and copper ore abound at the contacts between the granite and the rocks it pierced. The mineral wealth of the peninsula, especially its tin, attracted prospectors in early times, while mining has been one of the staples of Cornwall for centuries. Redruth and Camborne were the chief centres. Foreign competition and obso lete machinery brought about the collapse of the industry at the end of the 19th century, not before Cornish mining captains had become famous as metal prospectors the world over. The diminution of alluvial supplies of tin from abroad and the conse quent rise in the market price, is tending (1928) to cause a revival of mining. Fishing has always been important, the numerous good harbours giving security to the fishing boats. The south-western end of the peninsula is fortunately situated near the southern limit of the cold-water herring and the northern limit of the warm-water pilchard. The sea-faring traditions of the south-west are based on the facilities it gave as a training ground. The Drake and Hawkins type are needed no more now and fishing is a precarious existence and it is with difficulty that the fishermen turn to other activities.

The mild and sunny, but by no means dry, coast has led to the establishment of many health resorts, of which Torquay is the chief. This traffic is increasing with the motor-car.

The peninsula of the south-west, in its isolation, has developed in its people a sense of individuality and aloofness from the life of the English plain. It has many claims to live on a long and glorious past of its own. Saxon colonization never extended west of the Tamar and the Cornish language of Celtic affinity became extinct only in the 18th century. Exeter, once the out post of this old British kingdom, is now the administrative and ecclesiastical capital.

The Midland Plain.

Between the separate uplands just described, there extends a plain of Permian and Triassic rocks, which may conveniently be considered as an intermediate zone between the two main areas—the west and the east. To the eye it forms an almost continuous plain with the belt of Lias clays, which is the outer border of the Eastern Area; for although a low escarpment marks the line of junction, and seems to influence the direction of the main rivers, there is only one plain so far as regards free movement over its surface and the construction of canals, roads and railways. The plain usually forms a distinct border along the landward margins of the uplands of more ancient rock, though to the east of the Cornwall-Devon peninsula it is not very clear, and its continuity in other places is broken by inliers of the more ancient rocks, which everywhere underlie it.

In

the north-west we find a tongue of red rocks forming the Eden valley with Carlisle as its centre, while farther south these rocks help to form the low coastal belt of Lancashire. Triassic rocks also form the Cheshire Plain to the south of the Lancashire coalfield. The plain extends through Staffordshire and Worcester and Hereford forming the lower valley of the Severn. The red soil is good for agriculture which is very well developed in these counties. Orchards and hop-growing are also important, particu larly in Herefordshire. The flat surface and low level of much of this country has facilitated the construction of railways, canals and roads. Shrewsbury in its remarkable river loop was long a great fortress guarding ways into Wales and it remains a great market town to-day: it is also the centre of a considerable railway traffic. The great junction of Crewe is a further example of convergence of many routes on this lowland. The new and old red sandstone plains back against the Welsh plateau and there is a characteristic series of old towns beneath the hills where valleys open into the plain. Chester, Wrexham, Ruabon, Chirk, Oswestry. Shrewsbury, Ludlow, Leominster and Hereford may be named here.

An outcrop of the Coal Measures from beneath the newer rocks increases the importance of Bristol. This city, at the head of the navigation of the southern Avon, is the "gateway of the west." It has been from early times the wedge between Wales and Cornwall. Its importance grew with trade to and from Ireland and southern France, and later it became the great port for the New World with industries based on its commerce. The passing of the sailing boat, however, changed its fortunes; dock improvements and the refrigerator-boats (for fruit, etc.) are now reorganizing its trade and its industries are still considerable as well as varied. To the south-west is the plain of Somerset with its one-time woollen industry and its now famous cheeses and orchards and successful growing of the sugar beet. The plain is cut off from Bristol by the Mendip hills, an outcrop of Car boniferous limestone rising from beneath the newer rocks.

South of the Pennines, the Red rocks extend eastward- in a great sweep through the south of Derbyshire, Warwick, the west of Leicestershire, and the east of Nottingham, their margin being approximately marked by the Avon, flowing south-west, and the Soar and Trent, flowing north-east. South and east of these streams the very similar country is on the Lias clay. Several small coalfields rise through the Red rocks—the largest forms the famous "Black Country," with Birmingham as centre. This midland metropolis draws its population from the three counties of Warwick, Stafford and Worcester at the convergence of which it stands. Its development has been remarkable. It was off the main lines of communication in very early and Roman times and although it was associated with iron-smelting from the late middle ages and its population was increasing, it was still governed as a manor and so had no chartered corporation in the i 7th century when, under the Five-Mile Act, dissenters were not allowed to meet in corporate towns ; Birmingham in this way became a place of refuge and several families who thus came have provided leaders in scientific, industrial and social life.

With the use of coal its industries enlarged their scope and to-day it is the centre of the motor, rubber and artificial silk industry. Machine tools, wireless apparatus and iron goods of all kinds are made. Around Birmingham are a host of now related towns such as Wolverhampton, Tipton, Walsall, West Bromwich, etc. Some have old industries, e.g., saddlery at Walsall. On the eastern edge of the region is Coventry, also a centre of the motor trade, with recent interests in artificial silk, following old ones in natural silk. To the south-west of the Black Country is the Kidderminster area with its light sandy soils engaged in market gardening for the densely populated industrial areas. In the north-east of Birmingham smaller patches of the Coal Measures appear near Tamworth and Burton, where gypsum beds give the Trent water a special hardness suitable for brewing. Deep shafts have been sunk in many places through the over lying Triassic strata to the coal below, thus extending the mining and manufacturing area beyond the actual outcrop of the Coal Measures. A few small outcrops occur where still more ancient strata have been raised to the surface, as, for instance, in Charnwood forest, where the Archaean rocks, with intrusions of granite, create a patch of highland scenery in the very heart of the English plain; and in the Lickey hills, near Birmingham, where the prominent features are due to volcanic rocks of very ancient date. The midland plain, except in the industrial areas, is fertile and undulating, rich in woods and richer in pasture: the very heart of rural England. Cattle-grazing is the chief farm industry in the west, sheep and horse-rearing in the east; the prevalence of the prefix "Market" in the names of the rural towns is noticeable in this respect.

The manufacture of woollen and leather goods is a natural result of the raising of live stock. Leicester, Derby and Notting ham are manufacturing towns of the region. These towns were important in the middle ages. Nottingham, an old market centre at a river crossing, now manufactures machinery, motor cars, hosiery and cotton goods. Leicester is the great centre of the woollen hosiery trade—its tradition of woollen manufacture going back to the middle ages. Derby is a great entry to the dales, a railway centre and motor manufacturing town.

The midland plain curves northward between the outcrop of Magnesian limestone on the west and the Oolitic heights on the east. It sinks lowest where the estuary of the Humber gathers in its main tributaries, and the greater part of the surface is covered with recent alluvial deposits. The Trent runs north in the southern half of this plain, the Ouse runs south through the northern half, which is known as the Vale of York, lying low between the Pennine heights on the west and the Yorkshire moors on the east. The central position of York in the north made it the capital of Roman Britain in ancient times, and an important railway junction in our own.

The great fault line of the Humber brings the sea nearest to England's manufacturing midlands. Holderness is growing south ward into the Humber estuary, but its eastern coast is being rapidly denuded by the sea. The sheltered harbour of Hull, the meeting place of traffic by river and sea, is an important port. On the opposite side of the estuary is Grimsby, importing timber and exporting coal, but best known as the great fishing focus of England. Railways transport the catch in every direction.

The Eastern Area.

Five natural regions may be distinguished in Eastern England, by no means so sharply marked off as those of the west. The first is the Jurassic belt, sweeping along the border of the Triassic plain from the south coast at the mouth of the Exe to the east coast at the mouth of the Tees. This is closely followed on the south-east by the Chalk country, occupying the whole of the rest of England except where the Tertiary Basins of London and Hampshire cover it, where the depression of the Fen land carries it out of sight, and where the lower rocks of the Weald break through it. Thus the chalk appears to run in four diverging fingers from the centre on Salisbury plain, other forma tions lying wedge-like between them. The Mesozoic rocks of the south rest upon a mass of Palaeozoic rocks, which lies at no very great depth beneath the surface of the anticlinal axis running from the Bristol channel to the Strait of Dover. This is shown by the discovery of Coal Measures, with workable coal seams, at and near Dover.Eastern England is built up of parallel outcrops, the edges of the harder rocks forming escarpments, the sheets of clay forming plains. The rivers exhibit a remarkably close relation to the geological structure, and thus contrast with the rivers of the West. The Thames is the one great river of the region, rising on the Jurassic belt, crossing the Chalk country, and finishing its course in the Tertiary London basin, drawing its tributaries from north and south. The other rivers are shorter, and flow either to the North sea on the east, or to the English channel on the south.

The Eastern Area is the richest part of England agriculturally and is the part most accessible to the Continent. It is on this Wain that the various elements, Celtic, Roman, Saxon, Dane and Norman have been assimilated; it has been a melting-pot of peoples and cultures. The present population is so distributed as to show remarkable dependence on the physical features. The chalk and limestone plateaux are now usually sparsely inhabited and the villages of these districts occur grouped together in long strings, either in drift-floored valleys in the calcareous plateaux, or along the exposure of some favoured water-bearing stratum. In almost every case the plain along the foot of an escarpment bears a line of villages and small towns, and on a good map of density of population the lines of the geological map may be readily discerned.

The Jurassic Belt.—The Jurassic belt is occupied by the coun ties of Gloucester, Oxford, Buckingham, Bedford, Northampton, Huntingdon, Rutland, Lincoln and the North Riding of York shire. The rocks of the belt may be divided into two main groups: the Lias beds, which come next to the Triassic plain, and the Oolitic beds. Each group is made up of an alternation of soft marls or clays and hard limestones or sandstones. The low escarp ments of the harder beds of the Lias run along the right bank of the Trent in its northward course to the Humber, and similarly direct the course of the Avon southward to the Severn. The great feature of the region is the long line of the Oolitic escarpment, formed in different places by the edges of different beds of rock. The escarpment runs north from Portland island on the English channel, curves north-eastward as the Cotswold hills, rising abruptly from the Severn plain to heights of over i,000 ft.; it sinks to insignificance in the Midland counties, is again clearly marked in Lincolnshire, and rises in the North Yorkshire moors to its maximum height of over i,5oo ft. Steep towards the west, where it overlooks the low Lias plain as the Oolitic escarpment, the land falls very gently in slopes of Oxford Clay towards the Cretaceous escarpments on the south and east. Throughout its whole extent it yields valuable building-stone. The Lias plain is rich grazing country, the Oxford Clay forms valuable agricultural land, yielding heavy crops of wheat. The towns of the belt are comparatively small, and the favourite site is on the Lias plain below the great escarpment. They are for the most part typical rural market-towns, the manufactures, where such exist, being usually of agricultural machinery or woollen and leather goods. Bath, Gloucester, Oxford, Northampton, Bedford, Rugby, Lincoln and Scarborough are amongst the chief. These towns of old stand ing retain in many ways something of the life of England before the industrial revolution. Many of them, particularly Oxford and Bath, have been famous for centuries and retain respectively tra ditions of mediaeval and i8th century England. Lincoln, like Gloucester, is a Roman station and ecclesiastical centre, retain ing an importance at the present time as an administrative centre and market town with good railway connections. North of the gap in the low escarpment in which the town of Lincoln centres, a close fringe of villages borders the escarpment on the west ; and throughout the entire Jurassic belt the alternations of clay and hard rock are reflected in the grouping of population.

The Chalk Country. The dominating surface-feature formed by the Cretaceous rocks is the Chalk escarpment, the northern edge of the great sheet of chalk that once spread continuously over the whole south-east. It appears as a series of rounded hills of no great elevation, running in a curve from the mouth of the Axe to Flamborough Head, roughly parallel with the Oolitic escarp ment. Successive portions of this line of heights are known as the Western Downs, the White Horse hills, the Chiltern hills, the East Anglian ridge, the Lincolnshire Wolds and the Yorkshire Wolds. The rivers from the gentle southern slopes of the Oolitic heights pass by deep valleys through the Chalk escarpments, and flow on to the Tertiary plains within. The hills of the Chalk country rise into rounded downs, of ten capped with clumps of beech, and usually covered with thin turf, affording pasture for sheep. The chalk, when exposed on the surface, is an excellent foundation for roads, and the lines of many of the Roman "streets" were probably determined by this fact. The Chalk country ex tends over part of Dorset, most of Wiltshire, a considerable por tion of Hampshire and Oxfordshire, most of Hertfordshire and Cambridgeshire, the west of Norfolk and Suffolk, the east of Lin colnshire, and the East Riding of Yorkshire. From the upland of Salisbury plain, which corresponds to the axis of the anticline marking the centre of the double fold into which the strata of the south of England have been thrown, the great Chalk escarp ment runs north-eastward ; fingers of Chalk run eastward one each side of the Weald, forming the North and South Downs, while the southern edge of the Chalk sheet appears from beneath the Tertiary strata at several places on the south coast, and especially in the Isle of Wight. Flamborough Head, the South Foreland, Beachy Head and the Needles are examples of the fine scenery into which chalk weathers where it fronts the sea, and these white cliffs gave to the island its early name of Albion. The chalk supports only a small population, except where it is thickly covered with boulder clay, and so becomes fertile, or where it is scored by drift-filled valleys, in which the small towns and villages are dotted along the high roads. The thickest covering of drift is found in the Holderness district of Yorkshire. Of the few towns in the Chalk country, the same may be said as of those on the Jurassic belt, that their interest is historical or scholastic ; Salisbury, Winchester, Marlborough and Cambridge are the most distin guished. Reading manufacturing biscuits flourishes from its posi tion on the edge of the London basin. The narrow strip of Green sands appearing from beneath the Chalk escarpment on its north ern side is crowded with small towns and villages on account of the plentiful water-supply.

The Fenlands.—The continuity of the belts of Chalk and of the Middle and Upper Oolites in the Eastern plain is broken by the shallow depression of the Wash and the Fenlands. The Fenland comprises a strip of Norfolk, a considerable part of Cambridge shire, and the Holland district of Lincoln. Formerly part of the channel of a large river draining to join an extended Thames in the region now the North sea, the region is now low, flat and marshy, and for the most part within i5 ft. of sea-level; the sea ward edge in many places is below the level of high tide, and is protected by dykes as in Holland, while straight canals and ditches carry the sluggish drainage from the land. The soil is composed for the most part of silt and peat. In early times it offered se clusion to the hermit and saint, but a line of approach to raiders from the sea. The difficult nature of the country made its Isle of Ely the last stronghold of Hereward the Wake against the Nor mans. With the drainage schemes of the r 7th century, much land was reclaimed and the intensive agriculture of recent times is making for prosperity. Wheat, market gardening and sugar beet are important. A few elevations of gravel, or of underlying forma tions, rise above the 25 ft. level: these were in former times is lands, and now they form the sites of a few villages. Boston and King's Lynn are memorials of the maritime importance of the Wash in the days of small ships. The numerous ancient churches and the cathedrals of Ely and Peterborough bear witness to the lead given by religious communities in the reclamation and culti vation of the land.

The Weald.—The dissection of the east and west anticline in the south-east of England has given a remarkable piece of country, occupying the east of Hampshire and practically the whole of Sussex, Surrey and Kent. The sheet of Chalk shows its cut edges in the escarpments facing the centre of the Weald, and surrounding it in oval fashion. The eastern end of the Weald is broken by the Strait of Dover, so that its completion must be sought in France. From the crest of the escarpment, all round on south, west and north, the dip-slope of the Chalk forms a gen tle descent outwards, the escarpment a very steep slope inwards. The cut edges of the escarpment forming the Hog's Back and North Downs on the north, and the South Downs on the south, meet the sea in the fine promontories of the South Foreland and Beachy Head. The Downs are sparsely populated, waterless and grass-covered, with patches of beech wood. Their only important towns are on the coast, e.g., Brighton, Eastbourne, Dover, Chat ham, or in the gaps where rivers from the centre pierce the Chalk ring, as at Guildford, Rochester, Canterbury, Lewes and Arundel. Within the Chalk ring, and at the base of the steep escarpment, there is a low terrace of the Upper Greensand, seldom a mile in width, but in most places crowded with villages, ranged like beads on a necklace. Within the Upper Greensand an equally narrow ring of Gault is exposed, its stiff clay forming level plains of grazing pasture, without villages, and with few farmhouses; and from beneath it the successive beds of the Lower Greensand rise towards the centre, forming a wider belt, and reaching a con siderable height before breaking off in a fine escarpment, the crest of which is in several points higher than the outer ring of Chalk. Leith hill and Hindhead are parts of this edge in the west, where the exposure is widest. Several towns have originated in the gaps of the Lower Greensand escarpment which are continuous with those through the Chalk: such are Dorking, Reigate, Maidstone and Ashford. Folkestone and Pevensey stand where the two ends of the broken ring meet the sea. It is largely a region of oak and pine trees, in contrast to the beech of the Chalk Downs, The Lower Greensand escarpment looks inwards in its turn over the wide plain of Weald Clay, along which the Medway flows in the north, and which forms a fertile soil, well cultivated, and particu larly rich in hops and wheat. The primitive forests have been largely cleared, the early marshes have all been drained, and now the Weald Clay district is well peopled and sprinkled with vil lages. From the middle of this plain the core of Lower Cretaceous sandstones emerges steeply, and reaches in the centre an elevation of 796 ft. at Crowborough Beacon. It is on the whole a region with few streams, and a portion of the ancient woodland still remains in Ashdown forest. The forest ridges are poorly inhabited and towns are found only round the edge bordering the Weald Clay, such as Tonbridge, Tunbridge Wells and Horsham ; and along the line where it is cut off by the sea, e.g., Hastings and St. Leonards. The broad low tongue of Romney marsh running out to Dungeness is a product of shore-building by the Channel tides, attached to the Wealden area, but not essentially part of it.

The historical associations of the area are important as show ing it to be the great gateway into England from the Continent. The south-east is the pivot on which Britain balances its Conti nental influences. Its fertile soil made it a region of early settle ment and the large number of small ports along its shore line, giving choice of land to the little boats of early times driven by force of wind and tide, necessitated inland foci of the many landing places from the Continent, and in such positions there grew up Canterbury, characteristically the centre whence Roman Christians spread over England. The coast land remained dotted with active ports during the middle ages, the activity of the Cinque Ports (q.v.) and their satellites being famous. The mediaeval iron smelting dependent on the Weald forest lands ceased with the protection of the woodland and the use of coal on a large scale in other areas. It is possible that the recent de velopment of the Kent coalfield may recreate this industry on a different basis. The rapid development of the coalfield with its deep pits and problems of transport is the outstanding feature of the south-east, linked up as it is with a remarkable regional planning scheme calculated to avoid the overcrowded, dirty, ugly settlements with their many social difficulties that have hitherto characterized British industrial areas. Alongside this development is the extensive use of the region both as a holiday resort and as a residential area for the ever-growing metropolis.

The London Basin and East Anglia.—The London basin oc cupies a triangular depression in the Chalk which is filled up with clays and gravels of Tertiary and later age. It extends from the eastern extremity of Wiltshire in a widening triangle to the sea, which it meets along an irregular line from Deal to Cromer. It thus occupies parts of Wiltshire, Hampshire, Surrey, Kent, Berkshire, Hertfordshire, the whole of Middlesex, the county of London and Essex, and the eastern edge of Suffolk and Norfolk. The gravel hills are often prominent features, as at Harrow and in the northern suburbs of London ; the country is now mainly under grass or occupied with market and nursery gardens, and many parts, particularly Epping forest, still retain much oak wood. The coast is everywhere low and deeply indented by ragged and shal low estuaries, that of the Thames being the largest. Shallow lagoons formed along the lower courses of the rivers of Norfolk have given to that part of the country the name of the Broads, a district of low and nearly level land. Apart from the immense area of urban and suburban London (for its development see separate article) the London basin has few large towns. Nor wich and Ipswich, Yarmouth, Lowestoft, Harwich and Colchester may be mentioned in the north-eastern part, all depending for their prosperity on agriculture or on the sea; and a fringe of summer resorts on the low coast has arisen which depend on London's population. Reading and Windsor lie in the western portion beyond the suburban sphere of London. The Bagshot beds in the west form infertile tracts of sandy soil on which is situated Aldershot. The London clay in the east is more fertile and crowded with villages, while the East Anglian portion of the basin consists of the more recent Pliocene sands and gravels, which mix with the boulder clay to form the best wheat-growing soil in the country. This country appears to have had agricul tural associations from the Bronze Age times and even at that time there was a long tradition of human settlement. Mediaeval contacts with the Flemish weavers over the North sea gave an impetus to the East Anglian woollen trade. Foodstuffs were also exported thither and before the days of coal East Anglia was one of the most important industrial and most populous regions of England. Rural beauty called forth some of England's greatest landscape painters, while centuries of contact with the Continent and especially with Flemish weavers, both traders and artisans, gave her people a broad vision in agricultural, economic, political and religious life, a factor that has to be considered when we remember the part she has played at im portant crises in the history of England.

London itself, as primarily the focus of its basin and the lowest Thames crossing, is too large a subject for treatment here, but its complementary relation to the estuarine ports of the Continental shores and its consequent facilities as an entre pot, once England had become a great agent in the carrying trade, may be mentioned. The western suburban industrial growth, following application of electrical power in recent years, is por tentous.

Hampshire Basin.

The remaining Tertiary basin for con sideration forms a triangle between Dorchester, Salisbury and Worthing. The Tertiary rocks are enclosed by a vein of chalk which to the south appears in broken fragments in the Isle of Purbeck, the Isle of Wight and to the east of Bognor. On the infertile Bagshot beds is the large area known as the New Forest. Considerable sections are still under oak. The London Clay of the east is more fertile, but the feature of the district lies in its coastline, which is deeply indented like that of the London Basin. On a fine natural harbour, with deep water and a double inroad from the sea, stands Southampton—the focus of the Hamp shire basin. It is well placed for direct services to northern France and for transatlantic traffic. The development of a network of railways in its hinterland has facilitated its contact with London and the remainder of the British Isles. It has recently become the leading passenger port of England and has developed secondary interests and trades dependent on a large collecting and distribut ing centre. Portsmouth, with another fine harbour, has special ized on naval work. Bournemouth and Bognor, from their favour able position in the sunniest belt of the country, have developed as health resorts. Winchester was of old an inland focus behind a number of harbours and was thus in some ways analogous with Canterbury (see above) .The main features of the climate of England are dependent upon the passage from the North Atlantic of cyclones which are centres of low barometric pressure usually having phases of strong winds and much rainfall. Equally important for English weather is the extension of high-pressure systems (anti-cyclones) from the Continent or the neighbourhood of the Azores. These condi tions bring calm, dry, sunny weather in summer and dry cold weather in winter. The alternation of these conditions, and par ticularly the relation of England to the Continental high pressure region in winter and low pressure region in summer, cause the variety of atmospheric conditions experienced. These conditions are always modified locally by the configuration of the land and lead to contrasts of climate on the western highlands and eastern lowlands of England. The fact that England is surrounded by the sea obviates extremes of heat and cold at all times. The chief paths of depressions from the Atlantic are from south-west to north-east across England ; one track runs across the south-east and western counties, and is that followed by a large proportion of the summer and autumn storms. A second track crosses cen tral England, entering by the Severn estuary and leaving by the Humber or the Wash; while a third crosses the north of Eng land from the neighbourhood of Morecambe bay to the Tyne. In dividual cyclones may and do cross the country in all directions, though very rarely indeed from east to west or from north to south.

The average barometric pressure normally diminishes from south-west to north-east at all seasons. The direction of the mean annual isobars shows that the normal wind in all parts of Eng land and Wales must be from the south-west on the west coast, curving gradually until in the centre of the country and on the east coast it is westerly. The normal seasonal march of pressure change produces a maximum gradient in December and January, and a minimum gradient in April. In spring the gradient is often slight enough for a temporary fall of pressure to the south of England or rise to the north to reverse the gradient and produce an east wind over the whole country. The liability to east wind in spring is a marked feature of the climate especially on the east coast. The southerly component is most marked in the winter months, and westerly, predominating in summer.

Rainfall.—The Western or highland Area is the wettest at all seasons, each orographic group forming a centre of heavy pre cipitation. There are few places in the Western Area where the rainfall is less than 35in., while in the south-west, the Lake district and the southern part of the Pennine region the precipitation ex ceeds 4oin., and in the Lake district considerable areas have a rainfall of over 6oin. In the Eastern Area, on the other hand, an annual rainfall exceeding 3oin. is rare, and in the low ground about the mouth of the Thames estuary and around the Wash the mean annual rainfall is less than 25in. In the Western Area and along the south coast the driest month is usually April or May, while in the Eastern Area it is February or March. The wettest month for most parts of England is October, the most noticeable ex ception being in East Anglia, where, on account of the frequency of summer thunderstorms, July is the month in which most rain falls, although October is not far behind. In the Western Area there is a tendency for the annual maximum of rainfall to occur later than October. It may be stated generally that the Western Area is mild and wet in winter, and cool and less wet in summer ; while the Eastern Area is cold and dry in winter and spring, and hot and less dry in summer and autumn ; that is the Eastern Area approximates more closely to continental conditions. The south coast occupies an intermediate position as regards climate.

Temperature.

The mean annual temperature of the whole of England and Wales (reduced to sea-level) is about 5o° F, varying from something over 52° in the Scilly isles to something under at the mouth of the Tweed. The mean annual temperature diminishes very regularly from south-west to north-east, the west coast being warmer than the east, so that the mean temperature at the mouth of the Mersey is as high as that at the mouth of the Thames. During the coldest month of the year (January) the mean temperature of all England is about 40°. The influence of the western ocean is very strongly marked, the temperature fall ing steadily from west to east. Thus while the temperature in the west of Cornwall is 44°, the temperature on the east coast from north of the Humber to the Thames is under 38°, the coldest winters being experienced in the Fenland. In the hottest month (July) the mean temperature is about 6z.5 °, and the westerly wind then exercises a cooling effect, the greatest heat being found in the Thames basin immediately around London, where the mean temperature of the month exceeds 64° : the mean temperature along the south coast is 62°, and that at the mouth of the Tweed a little under 59°. In the centre of the country along a line drawn from London to Carlisle the mean temperature in July is found to diminish gradually at an average rate of I° per 6om. The coasts are cooler than the centre of the country, but the west coast is much cooler than the east, modified continental confli tions prevailing over the North sea. Oceanic influence penetrates the midlands especially by way of the Severn estuary. The Mersey estuary, being partly sheltered by Ireland and north Wales, does not serve as an inlet for modifying influences to the same extent ; and as the wind entering by it blows against the slope of the Pennines, it does not much affect the climate of the midland plain.The amount of sunshine experienced in various places varies naturally with the seasons, but there is more sunshine recorded for some coastal regions than for the inland areas. The regions of England that get most sunshine are the south-west and a belt covering the south coast around East Anglia to the Fen country. The north-east including the Pennine region and the whole of Yorkshire is very cloudy. It is estimated that in Britain mists, fogs and clouds obscure the sun for about two-thirds of the time that it is above the horizon.

In a general account of the geological history of England it is natural to include Wales since the two have been intimately con nected during geological time. Many of the major divisions of geological time are named after places or tribes in England or Wales, and it is fortunate that much of the early work on strati graphy was done in a country where representatives of rocks of nearly every age are exposed at the surface.

The Pre-Cambrian formation, on which the later fossiliferous strata were deposited, appears at the surface only in small and scattered exposures; but these give indications of the earliest geological time in the island. Small areas of gneiss are found in Anglesey, N. Wales, the Malvern Hills and Cornwall which sug gest that gneiss forms the basal rocks here as in Scotland and elsewhere. Following these, and probably considerably later in date, are certain volcanic and pyroclastic rocks found in Charn wood Forest, Nuneaton, Church Stretton, Malvern and elsewhere, whilst later still there are the red sandstones of the Longmynd which are in all probability of the same age as the Torridonian.

Thus, in the Pre-Cambrian there is evidence of a period of great earth-movement probably followed by violent volcanic action and finally the arid conditions of deposition of the Longmyndian. All these rocks were intensely folded, generally with a N.W.-S.E. strike, and formed the land masses and sea floor against and on which the first fossiliferous deposits were laid down.

Throughout Lower Palaeozoic times there was continuous deposition in a trough, one shore of which lay along the southern border of the Scottish Highlands while the other appears to have run more or less along the present line of the Pennines to Shrop shire and S. Wales, with a second trough occupying much of the area of the present English Channel. Naturally the actual posi tion of the shore-line varied from time to time. The Cambrian, Ordovician and Silurian together form one protracted marine period in this trough, during which the type of sediment was usually sand or finer mud with occasional thin limestones, whilst during the Ordovician period there were frequent and often im portant eruptions of volcanic material. These formed massive beds of lava and ash which now weather into mountainous ground with bold crags and are responsible for much of the finest scenery of the island, such as Snowdonia or the Lake District. Towards the end of Silurian times this marine trough became silted up and warped, and as compressional forces increased in intensity the whole area with the exception of Devon and Corn wall became land, while farther north the great Caledonian range of mountains was formed. These compressional forces are re sponsible for the strong slaty cleavage which is found in Wales and the Lake District in the older Palaeozoic rocks and gives rise to some of the most perfectly cleaved slates in the world. It was during the elevation of this great mountain chain and while much of England was land that vast amounts of material were worn from the newly formed hills to accumulate in the low lying elongated basins between the ranges. Thus the Old Red Sandstone with the earliest vertebrates, the fish, was laid down; while to the south, in S. Devon and Cornwall, the sea still re mained with its deposits of limestones and shales. In the neigh bourhood of the main mountain chain much igneous activity took place, but in England this is restricted to the intrusion of a few granite masses in the Lake District and elsewhere.

Coal Seams Formed.—After the gradual destruction of the land masses by denudation, the sea again invaded the area from the west and deposited extensive beds of Carboniferous Lime stone which now form the characteristic scenery of the Pennines, Peak district and Mendip hills. Later these seas were filled up with deltaic and estuarine deposits; and it was on the resulting swampy flats that a luxuriant vegetation grew and accumulated which eventually turned into the coal seams alternating with the sands and muds of the estuaries. The conditions of the crust once more became unstable and another period of mountain-building was initiated, but at this time the main range lay to the south in Brittany with secondary ranges on the line of the Mendip hills and in S. Wales.

The chief result of this uplift together with the residual moun tains of the former range in Scotland was the formation of a land with an arid climate, a large intermontane tract deprived of almost all moisture-laden winds; while the western shores of an inland sea reached to the line of the Pennines. In this sea the Magnesian Limestone was laid down ; on much of the land surface wind blown sands and breccias were accumulated, while in other places sheets of highly saline water deposited beds of salt and gypsum. These arid conditions continued to the end of Trias times.

There now followed a long period of comparative quiescence during which the sea invaded the area, probably from the south east and spread up in a Y-shaped gulf between the high land of Wales and the old rocks of East Anglia bifurcating on the Pennines, one branch running up to the west coast of Scotland and the other to the Yorkshire coast. This Y was broken by cross bars of greater rigidity than the rest of the trough, so that the deposits thin out both to the margins of the trough and also when traced along its length. The deposits are mostly clays and shallow water limestones full of fossils, showing that the waters supported abundant life. This state of affairs lasted throughout the Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous, and it was not until the begin ning of the deposition of the Chalk that any general submergence took place. In this deepening and clear sea the highly charac teristic deposit of the Chalk which gives rise to the familiar scenery of the Downs and Chiltern Hills was laid down.

At the end of the Cretaceous period important changes took place in the geography of the British islands and what had been an open sea was uplifted into land, all excepting an area in the south-east of England where Tertiary clays and sands were de posited. At this period the fringe of the great Alpine earth move ment reached England, causing the marked folding of the beds in the Isle of Wight and the less marked but equally important folds which located the London basin and Wealden anticline. The whole of England and Wales appears also to have received a slight tilt down to the east about that time, and this occasioned the removal by erosion of most of the western part of the Mesozoic sediments and also much from the Palaeozoic rocks of Wales and the Pennines.

While this was happening, widespread volcanic acivity was taking place in northern Ireland and western Scotland, but the only evidence of a similar occurrence in England is the Cleveland dyke in Yorkshire and possibly some intrusions of doubtful age in the Midlands. The quantity of material which was removed must have been enormous and the land appears to have been worn down to a gradually sloping surface out of which the higher hills rose as residual mountains. In East Anglia the shell-banks of the Pliocene were laid down, during a time when the climate was gradually changing from temperate to arctic, a change that continued, with fluctuations, until the end of the Pliocene when conditions were such that great ice sheets formed and covered most of England and Wales north of a line from the Severn estuary to the Thames.

There is considerable evidence that there were marked advances and retreats of the ice coinciding with marked oscillations of temperature and probably with considerable changes in the rela tive level of land and sea, but as the oscillations became less the climate gradually approached its present state and geological time merged into the historic period. (W. B. R. K.) Flora.—The spread of ice to the line of the Thames and Severn during the maximum Pleistocene glaciation, evidently impover ished the flora of the whole country most drastically. If, as seems probable, the land stood higher, it may be that some plants needing a more temperate climate survived on the then coasts. that is, on land now submerged. The sinking of the land after the Ice age, by converting a one-time peninsula into the British archi pelago, made the repeopling of the islands incomplete and the spe cies spreading in from the continent become fewer and fewer west wards. Remains of a post-glacial colony of Arctic plants, such as the dwarf-birch, have been found near Teignmouth, and patches of Arctic-Alpine flora still survive in Scotland and North Wales, on high ground. It is now generally agreed that while the gla ciers of north-west Europe were retreating, steppe conditions pre vailed widely, and there are plants on sandy soils in Norfolk that may be relics of these conditions ; they do not occur in the wetter west. The steppe period of the Upper Palaeolithic age was fol lowed by land-sinking and the spread of Atlantic climate, with growth of forest as a result.

It has been proved that pines, especially Pinus sylvestris, were widely distributed, and many remains of this tree occur in the submerged forests off the west coasts, as well as in the peats of the high lands, while what seem to be survivals of very ancient pine forests, with junipers, etc., still grow in north-east Scotland. The west of Ireland has some special plants, such as Saxifraga umbrosa (London pride), S. hirsuta, S. geum, Erica mediterranea, E. Mackaii, Daboecia polifolia (St. Dabeoc's heath), and Ar butus Unedo (strawberry tree). The south-west of England has Erica ciliaris, E. vagans, Lobelia wrens and a few other plants which seem to belong to the same association. Several species are common to south-west England and southern Ireland, and hardly occur elsewhere. Forbes interpreted this flora as a survival of a pre-glacial flora, but Clement Reid urged that it must be a post-glacial immigration, in view of the arctic condition which must have prevailed over the whole of the present area of the British Isles. The apparent conflict of view would be greatly diminished if it could be established that during glaciation the land lay higher, as this would make it probable that there were plants of the then south-west coasts of Europe which might well have maintained their coastal position as the coastline receded, and thus have established themselves in west and south Ireland and south-west England. Praeger has well named this flora the south-west European. The pennywort (Cotyledon umbilicus), not strictly included in the above group, is characteristic of walls and some stony hedges of the south and west of England.

The Forest period was probably beginning in the west when East Anglia was still under steppe conditions. There are two forest beds along various parts of the coast related to movements of land levels as well as to changes of climate, but this is a matter for geological and archaeological argument. The great develop ment of forest spread trees to far higher levels than they occupy at the present time ; their remains have been found by Lewis at a height of 2,6o0 ft. on Cross Fell. The lowland and the drier uplands grew oak forest (including the large oak Quercus robur), while the non-calcareous soils of the western hills were clothed with the smaller Quercus sessiliflora. It has been estimated that they grew up to levels exceeding their present limits by over 300 feet. The birch still grows above the upper limit of the oak. The beech has existed in Britain since early prehistoric times, though its invasion of Denmark was probably not long before the beginning of the last millenium B.C. It is highly characteristic of soil-covered slopes on the chalk hills, and it is often accompanied by the yew. Ash forests are specially important in limestone areas. Beech forests degenerate into scrub, and may even become grass land, as on parts of the chalk.

The wide extension of woodland in the period following post glacial land sinking, had considerable effect in limiting the sites of human occupation, but though Fox has shown in special detail that man reduced the forest, especially after Roman times in England, it is doubtful whether the reduction of the forest should be ascribed entirely to the efforts of man. The reduction of its upper limit on the hills might be sheer denudation or wastage due to sheep and goats, but its universality suggests rather a reduction of temperature, which is also a possible cause of the invasion of forests by peat bogs. It has been shown that, whereas in the heyday of the Swiss lake villages the water-level lay very low, the lake-dwellers civilization was brought to an end by the cooling of the climate and the increase in the volume of the lakes. The invasion of forest by peat bog in Scandinavia, the invasion of the previous oak forests of Denmark by the beech, which can stand less heat, all point to a climatic change i000 B.C., and evidence is being gathered for this from the Medi terranean region as well. At the same time it should be re membered that a beech wood, for example, accumulates acid humus in its soil, and so makes that soil unfavourable, in the long run, to renewal of the trees as they die. In some parts of the British Isles peat bogs are decaying; in others they are stable; in others again they are growing at the present time. The gorse or yellow whin (Ulex europaeus) is one of the most characteristic plants of Britain.

The cultivation of wheat in England finds highly suitable soil in the east, but the climate in many parts makes the harvest risky ; there may be an occasional drought there is far more often an excess of rain when the ears are ripening. Wheat is most largely grown in the south-east of the country, but the amount is diminishing. Oats, more tolerant of rain, ripen more assuredly, and it is noteworthy that the English oats-harvest is before the wheat-harvest, whereas in Poland the order is reversed. Barley is grown in many different areas. Hops are grown in large quan tities in Kent, and also on the Hereford plain. Beet-sugar is being established in East Anglia, Salop, Somerset, etc. Fruit orchards of apples, plums and cherries are important in Hereford shire, Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, Somerset, Devon, etc. Kent is well named the garden of England.

Fauna.

The wild fauna of Britain is characterized by its poverty, which arises from its devastation in the Ice age, its con version into an island as the climate was becoming temperate once more, and its density of human population. The wolf probably disappeared from England before Tudor times, the wild boar and beaver have also gone within historic times. The pure wild cattle have vanished, but their blood has influenced the races of domestic cattle in Britain. Red deer and roe deer and fox owe their preservation to the huntsmen of the country. The pine marten still occurs now and then, and the polecat is found in some localities still ; the badger and hare are of some importance, as are the stoat and weasel. The so-called brown rat has largely displaced an older-established smaller black race. The rabbit, a mediaeval introduction, has spread far and wide.Many of the birds that used to visit England in the breeding season come no longer. The draining of the Fens in eastern England has curtailed the breeding ground of many of the warblers, the crane and the bittern. The only peculiar British species, the red grouse (Lagopus scoticus), occurs in the northern counties, while the introduced pheasant is widely distributed. The most numerous bird is probably the meadow pipit, the most familiar the house sparrow.

Particular interest attaches to certain species of fresh water fishes, especially the salmon and trout, as they react both in pig ment and form to different environments, and there are thus many local peculiarities. Some fish (char, etc.) of the lakes of Westmorland and Cumberland are of interest in that they prob ably represent an old group, related to the trout, that formerly migrated to the sea, but with the tectonic changes that formed these lakes, their outlets were cut off. All that need be said of the invertebrates is that there exists in England no species not found on the Continent, while some of the invertebrates offer the best examples of the Continental origin of our fauna.

The subject of early immigrations into Britain can be followed, in outline, in the section of ethnology in the article EUROPE, and some of the archaeological correlations can be studied in article ARCHAEOLOGY. Here it must suffice to say that the old notion of a purely savage Britain civilized by Roman conquerors seems to be fading away. The persistence of features of older organization in Roman times is a noteworthy fact in several parts of south Britain. The much debated problem of the relations of Anglo Saxon invaders to pre-existing populations is still very difficult to follow to any reasonable conclusion, but it is often argued that the very large amount of medium and dark brown hair in British populations is a sign of survival of pre-Saxon elements, and we note the fact that there are numerous nests of dark types, apart from the Celtic fringe, notably in the Chilterns.

Early Settlement.

The view is often held, but sometimes disputed, that settlements in lowland villages in England began in Anglo-Saxon times, and introduced the system of common arable land held in strips, and cultivated on a two-field (one field each year), or a three-field (one field winter corn, one spring corn and one fallow) scheme. Leeds has recently brought forward evidence to suggest that there were valley villages on the gravelly patches near certain rivers in the Bronze age, the cultivation scheme of which is quite unknown, while Crawford's air surveys have revealed a scheme of hamlets high on the downs, with small enclosed fields, a system of cultivation presumably dating from the Early Iron age. The lynchets of the Downs are another old scheme of cultivation probably linked with definitive settlement. Whatever may be the facts about pre-Roman settlement, there can be no doubt that it utilized mainly the land that was not densely wooded, and that the post-Roman centuries in Britain, as in central Europe, saw a great extension of lowland rural settle ment above water meadows and in woodland clearings. Nor is there any doubt that the villages thus arising utilized the two-field, and probably the three-field, system of cultivation, whatever may be the truth as to the origin of such systems.The fair, tall, long-headed element in the British population was probably strengthened by Viking and Danish invasions, and the study of place names organized recently by Allen Mawer, will throw further light, it is hoped, on the distribution of these populations; it appears that the abundance of Scandinavian names around the Solway firth, and in Cumberland and Lancashire, indi cates an influence that had much to do with the definitive isolation of Celtic-speaking elements in Strathclyde from Celtic-speaking peoples in Wales. It seems clear that at this period the Celtic speaking inhabitants were still under tribal organization, with the homesteads of the herdsmen on the hill sides, and probably with the custom of moving up to the hill pastures in summer.

Norman Period.

The Norman period witnessed a consider able extension of rural settlement along with the growth of manors, and the regions which were once, or are still in some cases, rich in parish churches of Romanesque (Norman) archi tecture, might be mapped to give clues to the spread of popula tion. At the same time there was urban and commercial growth followed by the establishment of bishops' sees in regional capitals, especially such as had communication by water with the Con tinent. The placing of bishops at Lincoln, Norwich and Exeter is typical here. At the same time comes the rise of Bristol in connection with trade to Ireland, where Dublin became for a while a dependency of Bristol. An estimate of the population of England at the time of the Domesday survey makes the total 1,500,00o, and, especially after a measure of order had been established under Henry II., and a further measure under Edward I., it seems to have grown, for estimates of the total just before the Black Death (1348-49) give totals varying from 2,500,000 upwards. The tendency to specialize in wool seems to have been promoted by shortage of labour due to the Black Death, and the claim has been made that the Cistercians had, prior to this, done a good deal to foster the wool trade. Some manors fell into decay, owing both to loss of population and to the spread of sheep farming and, with the decay of manorial restrictions and the rise of wool trade, movement began to be a little freer, and money payments began to take the place of dues in service. With the rise of the wool trade came the enclosure of common lands, sometimes old arable, more often old woodland and hill pasture, with the result that population and the wool trade grew in several areas such as the Cotswolds. It is interesting to note that, at the Ref ormation, bishoprics of Chester, Gloucester, Oxford and Peter borough were created; this seems to mark a considerable inland development in England.

Tudor, Stuart and Hanoverian Periods.