Point Woodcut Lithography

POINT ; WOODCUT ; LITHOGRAPHY.) Pauli, Inkunabeln der Radierung (Graphische Gesellschaft, Berlin, 1906 seq.) ; K. Zoege von Manteuffel, Die Radierung; M. C. Salaman, The Great Etchers from Rembrandt to Whistler (London, 1914) ; H. W. Singer, Die moderne Graphik (2nd ed., Leipzig, 192o) ; Sir Frank Short, The Making of Etchings (London, 1888). (A. E. P.) Materials.—The essentials for producing an etching are: (I) A metal plate; (2) a mordant resist or "ground"; (3) a point which will cut through the ground; (4) a mordant ; (5) ink, paper and press. For fine work artists generally prefer copper, for coarser, simpler designs zinc is equally capable of yielding the best results. But from the closer-textured copper a greater range in light and shade is possible.

Before applying the "ground" the plate's surface must be cleaned thoroughly, to allow as perfect contact as possible. This may be done by means of any solvent—turpentine, benzine, petrol or ammonia—with whitening and a soft rag. Tarnish may be removed with vinegar (or acetic acid) and common salt.

The Ground.

Rembrandt's is said to have been: (a) Virgin wax, I oz. ; mastic, oz. ; asphaltum or amber, oz. ; or (b) wax, 2 oz. ; Burgundy pitch, i oz. ; common pitch, oz. ; asphaltum, 2 ounces. A similar recipe is in use to-day. The ingredients are melted together carefully—first the asphaltum, then the wax, and last the pitch or mastic. The mixture should be allowed to boil up two or three times and then poured into warm water to set, being formed into suitable balls while in the water.A transparent ground may be manufactured with five parts of wax and three parts of gum-mastic by weight. The ground is applied by melting on the heated plate and spreading as finely and evenly as possible by means of a so-called "dabber" or leather-covered roller. To make the dabber, a circular card about 2 in. in diameter is cut, a wad of cotton-wool placed upon it and the whole covered with fine kid or silk. Before the ground cools the usual though by no means universal practice is to smoke it by passing the inverted plate backwards and forwards—taking care never to rest at one spot—over wax tapers or an oil lamp. This dark surface shows the line and strengthens the ground as a resist. In place of smoking Rembrandt is said to have used a white lead powder. This has the advantage of causing the line-work to appear dark on a light surface, like drawing with a grey pencil on paper. Quite recently a Scottish etcher, Henry Daniel, has dis covered that, for this purpose, oxi-chloride of bismuth has admir able qualities. It is spread over the still slightly-warm ground with a very soft, full brush. Not being really incorporated with the ground it is attacked and removed by the acid when biting begins, but this is no great disadvantage. Many etchers prefer a liquid made by dissolving ordinary ground in ether or chloroform. This is poured very quickly over the plate (in a tray) and the residue returned to its bottle.

Points.

Every etcher has a favourite point. A most satis factory and easily made one is a long gramophone needle pushed butt-foremost into a pen-holder and secured with sealing-wax. This is an ideal, not too sharp yet fine tool. Another, which serves equally for additional dry-point work, is the engineer's pricker, the points of which can be changed and reversed while in the pocket. The object of the needle is to remove the ground without scratching too much into the metal. A very sharp point destroys freedom, and causes irregularity in the attack of the mordant.

Biting.

When the drawing has been made upon the prepared wax surface with as steady and equal pressure as possible, comes the biting or fixing of the design. If the plate is to be entirely submerged the back also must be first coated with a resist. For such a purpose a liquid varnish is necessary, as to re-heat the plate would destroy the lines drawn. The best ingredients are methyl ated spirit and shellac (in proportion two to one) to which some black pigment has been added to cause less fluidity and allow the varnish to be visible when dry.Three mordants are commonly employed at the present day. The first, and most used by artists, is nitric or nitrous acid mixed with an equal quantity of water. The second, the so-called "Dutch mordant" is prepared by dissolving oz. potassium chlorate in 5 oz. of hot water, and adding i oz. of hydrochloric acid. The third is iron perchloride, most used by process-etchers. Artists probably prefer nitric because it is much the most rapid in action, and because the constant and obvious ebullition makes easy the detection of any over-looked line or dust-hole in the ground. The other mordants attack more gently without bubbles, consequently "foul-biting," as it is called, may easily go on unnoticed until too late. On the other hand, iron perchloride, while reasonably fast, bites more deeply in proportion to the width of line, as the edges are not broken away and the ground undermined as happens with strong nitric. The iron also darkens copper, permitting the lines to be more easily watched if used with an unsmoked ground. Its only drawback is the formation of sediment, which retards the action at the bottom of the but can be dispersed by keeping the bath in motion. If rocking is not sufficient, the plate must be bitten inverted—resting upon slips of wood or other material not affected by the mordant—after which the deposit can be dis tinctly seen at the bottom of the dish. Full (saturated solution) strength is too thick for fine etching, and half that or a little more is far quicker than the cold "Dutch" bath. In many ways iron perchloride is the most reliable of the three mordants.

Before beginning the biting it is well to place the plate in a bath of commercial acetic acid for a few minutes, in order to re move impurities which may otherwise clog the lines—perspiration from the hand while drawing, for instance. This is particularly needful when one portion of the drawing has been made consider ably prior to another. It allows all parts to be attacked simul taneously, which in the case of a delicate distance, for instance, needing but a very short biting, is of the utmost importance.

Various Methods.

In working the more orthodox plan is to complete the drawing entirely before beginning to use the acid. Then the plate, placed bodily in the bath, is left suffi ciently long for the most delicate lines to be etched. The deter mining of the exact moment for removal is largely a matter of experience. The plate is then washed with water, carefully dried by means of blotting-paper, and those lines which are deemed of sufficient depth "stopped out" with a fine brush and the shellac varnish. Allowing this to dry, the process is then repeated until those lines which are required to be deepest of all are bitten when the plate is, for the time at least, finished. In the earliest days of etching no stopping out was reverted to, Diirer and Hopfer biting their lines to one depth only; and, generally speaking, the fewer stoppings the simpler and better the result.Then there is the method employed by Haden. It is the reverse of the preceding. With the grounded plate placed in the bath, the artist begins by drawing those passages which he de sires to be the strongest of all. As the lines are drawn the acid attacks them and the etcher passes on to the next darkest parts, ending by drawing the faintest lines immediately before removing the plate from the bath. This obviously requires great speed and certain judgment, allowing of no mistakes or hesitation. It is the resulting spontaneity which so charms in Haden's work.

Lastly, there is the compromise between the above processes re sorted to by Whistler in his later manner. The drawing is more or less completed—in Whistler's case out of doors—then a little acid is poured upon it and (controlled by a feather) moved about here and there, being permitted to stand longer on some lines, less long on others, until the whole is bitten without recourse to stop ping out. At the same time new lines are added where required to give strength or closer texture, light lines often crossing stronger ones (as also in Haden's method) and yielding less formality in the result than is easily obtainable by the older way of working.

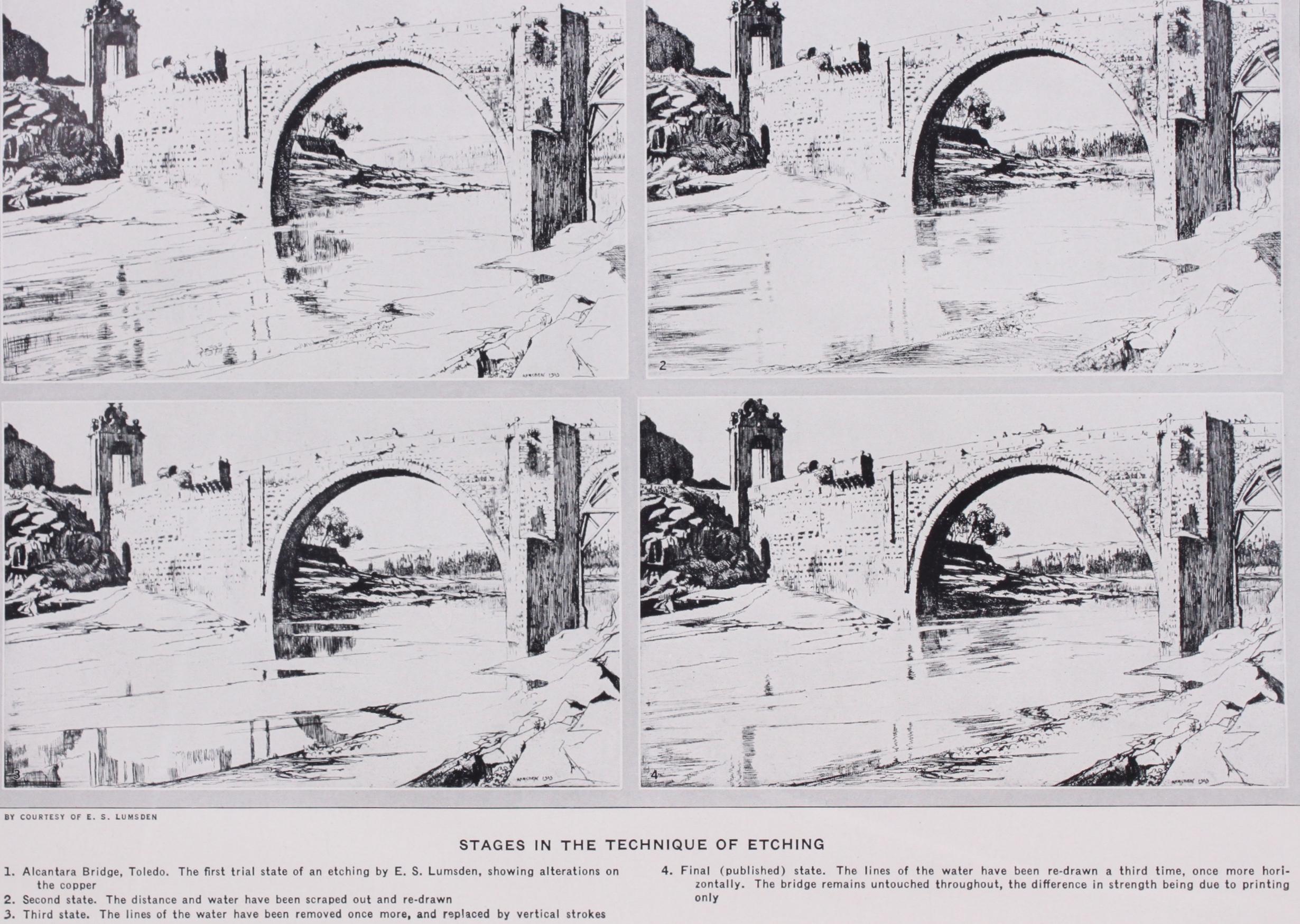

But the etcher is by no means compelled to do the whole of the work upon a single ground. It is often expedient to do part only, remove the wax by means of turpentine or other solvent, pull a proof as a guide, re-ground the plate and continue. In re-grounding (which cannot safely be done with the roller) care must be taken to fill in the already bitten lines, as their edges are very liable to be attacked in renewed biting. Insufficiently bitten work can also be rebitten by carefully laying a ground on the surface only (here the roller is perhaps safer than the dabber) while leaving the lines open. It is a hazardous undertaking, except where already deep lines are concerned, and generally results in loss of definition.

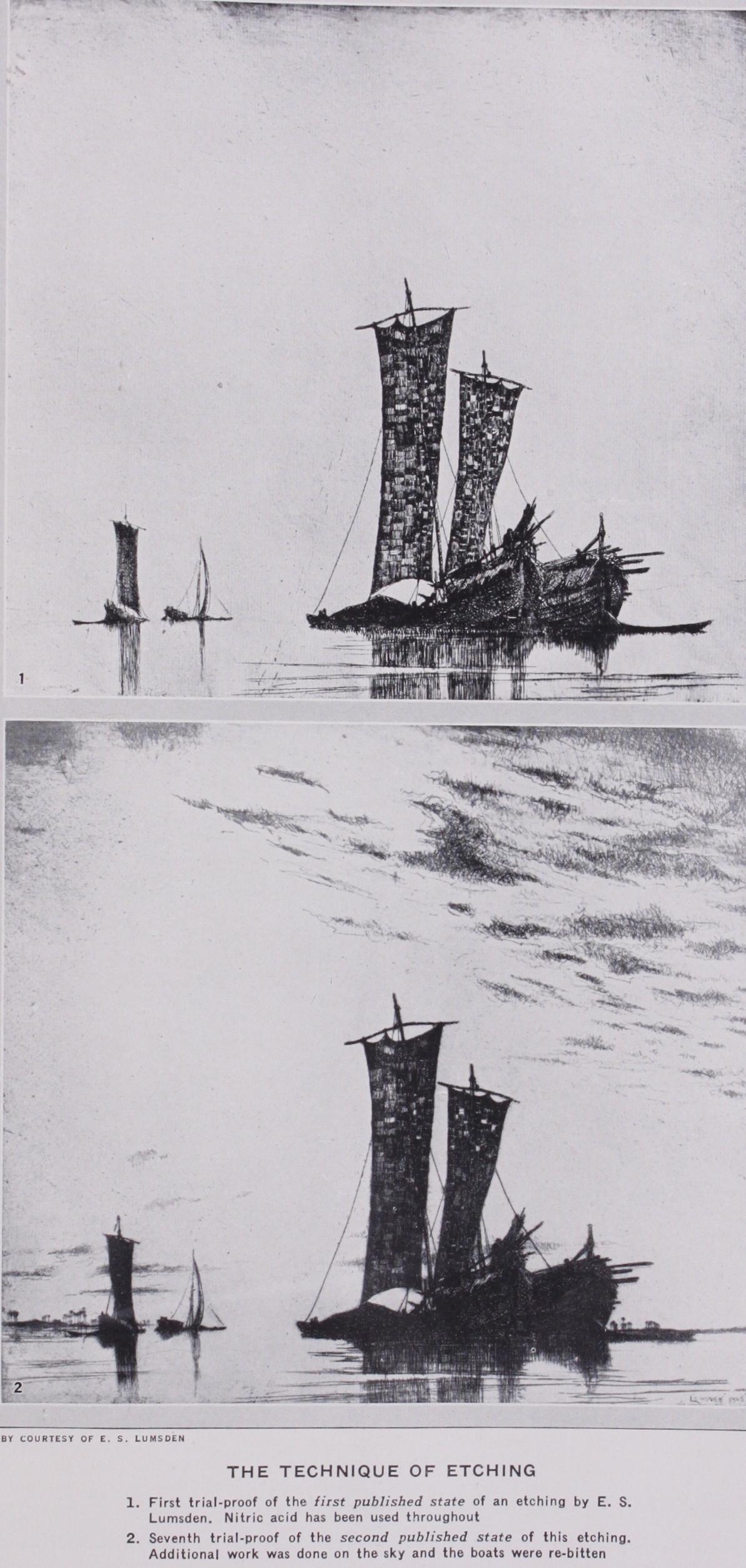

Proving.—When biting has been accomplished by one method or another and ground and backing removed, the plate is ready for "proving." The result will be the first state of the plate. Any additional work constitutes a new state, without relation to the number of proofs printed. There may be one only or soo of each state ; but the removal of a single line or adding of, say, a date creates technically a further state. Even where the artist, realiz ing that his alterations were a mistake, returns as nearly as pos sible to his original, the last will still be the third state, if proofs of the two previous ones are preserved. For instance, the eighth state of Whistler's "Bridge" is only distinguishable from the first by careful examination of both, though intermediate proofs are easily recognized. These working states are known as trial-proofs, as when an edition of more than one state is published the tentative trials are ignored—only those issued receiving the titles of first, second or third published states, e.g., Haden's "Agamem non." Few etchings are left untouched after the first ground is removed, and it is as often necessary to cut out lines as to add them. For this a "scraper" is required. It is a tool difficult to handle and to sharpen. To remove the marks left by the scraper, snakestone is used with water, and to regain the polished surface charcoal and water and finally oil or plate-polish. Another useful etching tool is the polished steel "burnisher." With this light scratches may be rubbed out or over-heavy lines reduced. With these implements and soft rag almost anything is possible in the way of alteration. The pulling of the proof itself is one of the most fascinating of the processes which together go to the making of an etching. And yet quite a number of etchers delegate this— the real birth of the final work—to a professional printer! Printing.—The expense of a really good roller press is per haps partly responsible, but a good printing press is an essential. Small machines which have little power are worse than none at all, as their results are apt to discourage the beginner. The more delicate the line in the plate the more pressure—"pinch"—is neces sary. The best modern presses are geared, and the large double geared ones can be run with little physical exertion. The old machines were built with wooden rollers and travelling-bed, the modern entirely of iron and steel. The printing-ink is formed by grinding Frankfurt or French black powder (mixed usually with umber or burnt sienna to add warmth) with burnt linseed-oil. The burning of the oil thickens it and makes it more adhesive. Sev eral strengths are used, which yield very different results. When mixed and well ground the ink should be sufficiently stiff not to fall quickly from the palette knife, and it is spread solidly over the surface of the heated plate by a roller or the older dabber.

The roller is made of gelatine, covered by some material to prevent adhesion when the warmth from the plate softens its composition. Stockinette is excellent for the purpose, but great care is needed to avoid any scratching edge at the seam. The roller's length should be about 3 in. and its diameter 2 2 inches. The ink, after being well worked into the lines and spread evenly all over the plate, is wiped off gradually by means of pads of stiff book-muslin or Swiss-tarlatan. The hand presses firmly and equally—avoiding a scooping action—as if polishing the metal. A firm pressure forces the ink into the lines while removing it from the surface—all but a very fine film. A "clean-wiped" proof is finally polished by the base of the palm.

To soften and enrich the clean-wiped plate a piece of clinging muslin may be dragged lightly over the surface, pulling the ink a little out of the lines. This is called retroussage, "dragging" or "bringing up." It can also be done by going over the plate once more with the fully charged printing muslin, but this leaves a slightly granular effect upon the surface as well. Wiping is capable of great variation and the strength of oil plays an important part in the way in which the ink comes off the surface. An etching is never wiped so that no film of oil remains. A good printer will consider what colour, of ink and paper, will produce the best re sult ; whether the plate shall be clean or only rag wiped, etc.

Paper.—Many etchers prefer old paper because the decay of its size renders it soft and pliable, and consequently more readily forced into the lines in passing between the rollers. Its colour is also more beautiful and often it is made of better material— that is, linen rags unspoilt by modem bleaching with dangerous chemicals, or adulterated with dressings.

The paper is well damped before use but should have no excess moisture on its face. This may refuse the surface film of oil on the plate and white granulations appear on the proof. Very thin oil is specially liable to this. Before beginning to print, the edges of the plate should be examined and filed smooth, to prevent the paper being cut. When the inking and wiping has been ac complished, the warm plate is laid upon the travelling-bed of the press, a sheet of paper is taken from its damp pile, examined for hairs or dust, and placed face down upon the plate, one or two sheets of new soft blotting-paper laid over it and five or six thick nesses of printing blanket over all. The blanket is of two quali ties—the two nearest the plate being fine "fronting" and the rest of coarser thicker material. When everything is in place the whole is pulled between the rollers, once only. Removing the blankets, the printing and blotting papers are peeled off the plate in one solid piece. When dried, the proof can be removed and flattened.

Soft-ground.—This method—the French vernis mou—is much less practised than it was in the early 19th century. The line somewhat resembles a chalk drawing. Its granulated texture renders it very suitable as a basis for aquatint, but its own quali ties were fully exploited by that great master, Cotman. Every thing depends upon the addition to the ordinary etching ground of tallow, usually an equal quantity, in hot weather less. This makes a very clinging compound, with which the plate is covered in the normal manner; but instead of being directly drawn upon, a sheet of grained paper is placed over the surface and the draw ing executed upon this with a pencil, care being taken to avoid contact with the paper otherwise than with the point. When the design is complete the paper is peeled off, taking with it those portions of the ground corresponding to the lines drawn. The stronger the pressure the more ground will stick to the paper and the wider the line exposed ready to be bitten by the acid. The grain of the paper will show in the character of the bitten line. Except that stopping-out is hardly required, the biting is carried out exactly as described above. The line relies upon breadth rather than depth for variation. A smooth paper will hardly produce any result, but tissue is excellent. Tissue paper is also serviceable for re-working, as it is semi-transparent.

Aquatint.--Instead of with line aquatint deals with tone in broad masses. In most of his plates Goya, the greatest exponent of the medium, employed an etched line as guide and basis for the tonal work, but not in all. (See AQUATINT.) A variant of aquatint is to form the porous ground by passing an ordinary wax ground through the press several times in con tact with sand-paper ; this is known as "sand-grain." Its fineness depends upon the quality of the paper and the number of passages through the rollers. Joseph Pennell produced some good plates in this manner.

Pen-method.—This has recently been revived in London. It was used by Gainsborough in conjunction with aquatint, and though hardly possible to employ for fine work, its quality blends better than that of the needle line with tone work. The drawing is made upon the bare plate—good results have been obtained on steel in recent times—with a pen or brush and ordinary ink or a soluble gum—gamboge and water is excellent. When dry (but not more than a day old, or it will harden), an etching ground is laid over it, not too thickly. When this is hard the plate is submerged in water for half an hour or so, whereupon the ground above the lines will come away as the ink dissolves. The lines can then be bitten in the usual manner.