War and Revolution

WAR AND REVOLUTION Revolutions of 1848.—A revolutionary movement of a demo cratic and nationalist character common to nearly all the European States completely transformed the political life of Europe. It be gan in Italy with a local revolution in Sicily in Jan. 1848, and of ter the revolution of Feb. 24 in France the movement extended throughout the whole of Europe with the exception of Russia, Spain and the Scandinavian countries. In Great Britain it amounted to little more than a Chartist demonstration and a republican agitation in Ireland. In Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark it manifested itself in peaceful reforms of existing in stitutions; but democratic insurrections broke out in the capitals of the three great monarchies, Paris, Vienna and Berlin, where the Governments, inexperienced in the art of repression and rendered powerless by their fear of "the revolution"—to them a mysterious and irresistible power—did little to defend them selves. The revolution was successful in France alone ; a republic and universal suffrage were established, but the quarrel between the supporters of the republique democratique and the partisans of republique domocratique et sociale culminated in a workers' insurrection in June 1848. In Austria where the new ministers promised to grant constitutions, the monarchy withstood the storm, and in Prussia King Frederick William, who led the movement for the unification of Germany, hoisted the black, red and gold flag that had become the symbol of German unity. The German Governments agreed to the convocation of three constituent assemblies at Berlin, Vienna and Frankfurt by which democratic constitutions were to be drafted for Prussia, Austria and Germany. In Italy, at first, the revolution only took the form of a nationalist rising against Austria led by the king of Sardinia under Italian tricolour, the "white, red and green." The republic was proclaimed in 1849, and then only in Rome and Tuscany. Within the Austrian empire the nationalities subjected to the German Government of Vienna agitated for a national government and Hungary succeeded in organizing itself on an autonomous basis.

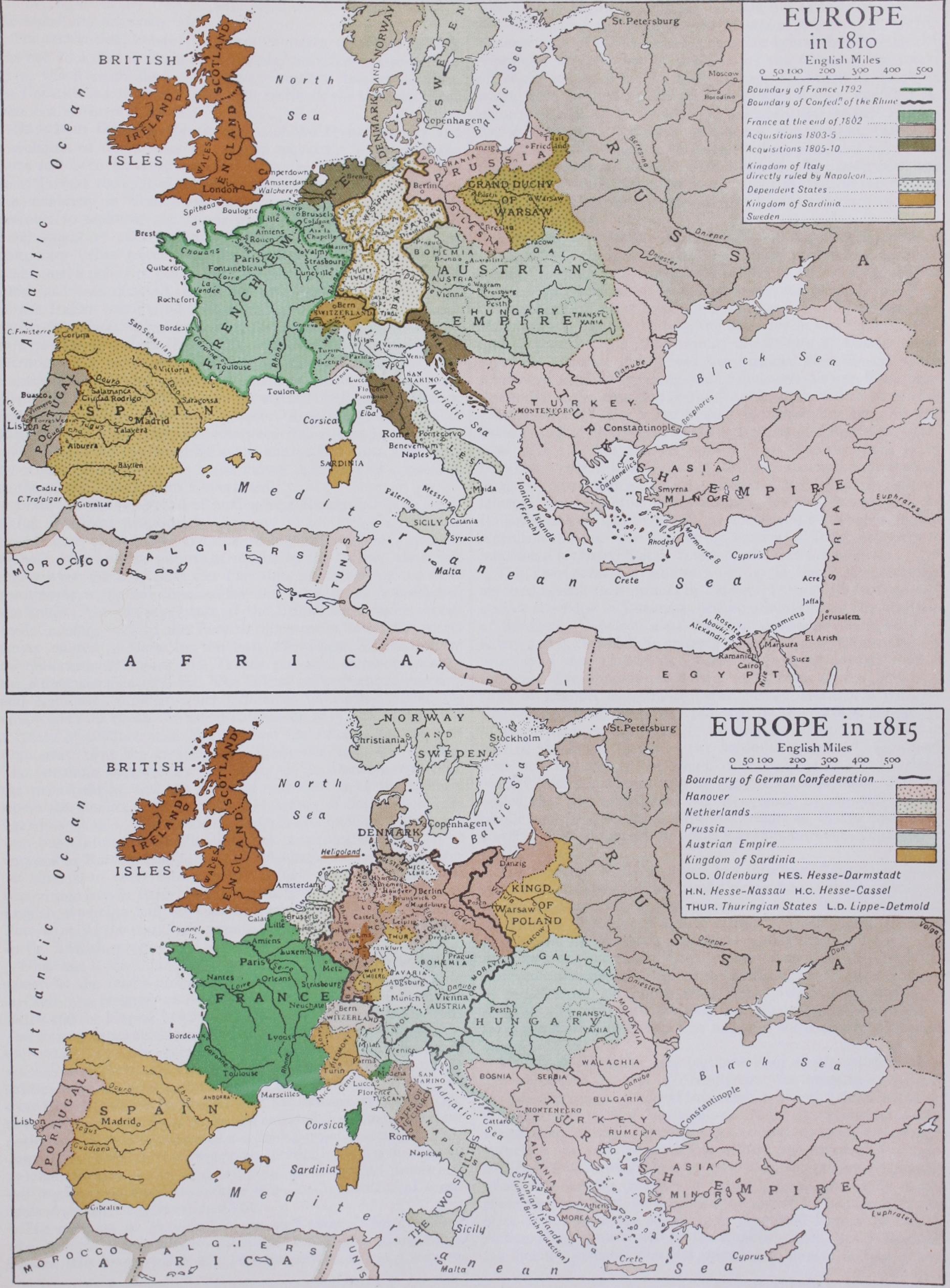

This upheaval seemed to indicate a redistribution of the ter ritories of Europe. In the name of the Provisional Government in France, Lamartine declared that the treaties of 1815 were no longer valid in the eyes of the French republic, but he added that he accepted the territorial delimitations effected by those treaties. France did not lend her support to the revolutionaries in Europe.

Reaction in Europe.

The restoration had commenced even before the revolution was over and it was accomplished by the armies that had remained faithful to their respective Governments. Military repression was first employed in Paris by Cavaignac against the insurgents in June, and by Windischgrtitz on June 17th against the Czechs in Prague, and later by the Austrian army in Lombardy and in Vienna ; then in Berlin in December, and in 1849 by the Prussian army in Saxony and Baden. Order was only restored in Rome by French intervention, and in Hun gary with the help of the Russian army. The king of Prussia, having refused the title of Emperor offered to him by the as sembly, sought to achieve the unity of Germany by a union be tween the German princes. Austria and Russia, however, com pelled him to abandon his design by the Convention of Olmgtz in 185o. The immediate result of the reaction became manifest in the withdrawal of liberal democratic or nationalist concessions which had been made during the revolution : universal suffrage, liberty of the press and of assembly. Absolute monarchy was re-established in Germany, Austria and Italy, and the Govern ments, in alliance with the middle classes and the clergy, who were terrified by the socialist proposals, strengthened the police forces and organized a persecution of the popular press and associations which paralysed political life. In France the re action led to the coup d'etat against the assembly on the part of Prince Napoleon on Dec. 2, 1851, and the re-establishment of the hereditary empire in 1852.

The restoration, however, was not complete, universal suffrage was not abolished in France; in Prussia, the Constitution of Jan. 185o, which established an elective assembly, and, in Sardinia, the Constitution of March 1848, were retained; the signorial rights were not restored in Austria.

Napoleon III.

The proclamation of the French empire was a violation of the treaties of 1815 by which the house of Bona parte had been for ever excluded from the French throne. The great Powers recognized Napoleon III. because he re-established the monarchy in France and because he promised in a secret protocol to maintain the status quo. Nicholas of Russia, how ever, sought to address him only as "bon ami" instead of the customary "cher f rere." Absolute master of France, Napoleon abandoned a policy of peace. As the enemy of the treaties of 1815 which had been directed against his own family and as the friend of the Italian patriots who were exasperated by Austrian domi nation, Napoleon wished to destroy the work of the allies of 1815, to expel the Austrians from Italy, and to obtain an increase of territory as a recompense. It was his desire both to help na tionalities to become states and to annex territories to his em pire. For this two-fold purpose he worked with the revolution, and was ready to go to war in order to rearrange the map of Europe. He knew that his ministers did not approve of his policy and so he concealed his plans and actions from them, and by means of secret agents made moves that were in opposition to the official policy of his Government.

Crimean War.

Proud of having kept Russia free from revo lution, Nicholas proposed to England (Feb. 1853) a plan for the division of the Ottoman empire but encountered a decided refusal. Next, on the pretext of regulating the conflict which had arisen over the holy places in Palestine, he despatched to Con stantinople a special mission for the purpose of intimidating the sultan; but the arguments of the British ambassador, Strat ford Canning, decided the Turkish ministers to reject the secret treaty offered to them by the tsar, whereupon Nicholas broke off diplomatic relations with Turkey and sent troops to occupy the Rumanian principalities. The British government intervened, and Napoleon, although quite indifferent to Turkey, seized the opportunity to break the allied entente of 1815 and to conclude a treaty of alliance with England and the sultan. For the first time since 1815 the great Powers made war upon one another. The Russians, defeated by the Turks on the Danube, evacuated the principalities, and the scene of war shifted to the Crimea, where the conflict went on until the capture of Sebastopol. (See CRIMEAN WAR.) The Austrian Government took no part in the war, but discussed with the allies the conditions of peace to be imposed in Russia. Napoleon took advantage of the Franco-Brit ish alliance to enter into federal relations with Queen Victoria who visited him in Paris; this being the first occasion on which an English sovereign had set foot in Paris since the 15th century. The charm of the emperor's personality made a strong impression on the English queen.Nicholas I. died in March 1855, and his son Alexander II. agreed to the terms proposed by Austria : peace was concluded in Paris by a congress of representatives of the great Powers, the sultan and the king of Sardinia who had sent troops to the Crimea. The Powers guaranteed the integrity of the Ottoman empire, and the sultan, in return, promised to introduce reforms; the Black sea was neutralized and closed to ships of war; Rumanian princi palities were declared autonomous ; a part of Bessarabia was re stored by Russia to Moldavia; and the concert of Europe was re-established and completed by the entry of the Ottoman empire. Acting as the representative of a united Europe, the congress laid down (1856) the rules of maritime international law in time of war and forbade states to give letters of marque to privateers; this maritime declaration marks a stage in the creation of a rec ognized system of international law.

The congress of Paris was a personal triumph for Napoleon who had for the first time welcomed a European Congress to France. His house which had been proscribed in 1815, was re stored to the society of reigning families and he saw the time was ripe for seeking to obtain the aid of one of the great Powers in the execution of his plans in Europe. He approached Russia with a promise to assist her in ameliorating the terms of the treaty of 1856; and in order to quiet the apprehensions of England, which were aroused by his friendship with Russia, confided his plans to Prince Albert in 1857. In the same year he met Alexan der at Stuttgart; a project of alliance was drafted, Napoleon proposing to ally himself with Russia so long as he was not forced thereby to embroil himself with England. The interview was abortive, for while Napoleon sought allies to destroy the treaties of 1815, the European sovereigns would only negotiate with him to maintain them.

The Union of Italy.

Thus frustrated, Napoleon determined to act alone. He met Cavour, the foreign minister of Sardinia, secretly at Plombieres and promised him to free Italy up to the Adriatic ; in exchange he demanded Savoy and Nice. Daunted by the opposition of his ministers, his court, and the other sovereigns, Napoleon did not dare to take the initiative in making war. Vic toria implored him in the name of the welfare of Europe to re spect the treaties ; and it was the Austrian Government which summoned Sardinia to disarm and commenced the war. The Italian war ended in the expulsion of the Austrian from Lombardy. (See ITALIAN WARS.) But when Prussia mobilized her army on the French frontier, Napoleon ceased operations and sought an inter view with the Austrian emperor at Villa Franca where (July 1859) they arranged the terms of the peace that was subsequently signed in November at Zurich. Austria ceded Lombardy but re tained Venetia—a cruel disappointment for the Italians. All the Italian States were to be united in a confederation. It appears that Napoleon did not wish for the unification of Italy, but only to establish a confederation of States on the German model.The Provisional Governments set up in the States that had revolted against their princes in Tuscany, Parma and Modena, and against the Pope in Romagna, desired annexation to the kingdom of Sardinia. Napoleon gave way but demanded the cession of Savoy and Nice which he annexed to France, notwithstanding his promise of 1859 that he would seek no personal advantage from the war. The annexation of Nice and Savoy aroused the mis trust of Europe, and France found herself henceforth isolated. The unification of Italy was achieved by the Sicilian expedition of the republican Garibaldi (q.v.) and by the occupation of a part of the Papal States by the Sardinian troops. These states were now annexed to the kingdom of Sardinia and Victor Em manuel took the title of king of Italy, after a plebiscite had re vealed that the annexation had been made by the will of the people and in accordance with their right to decide their own destiny. A revolutionary principle was thus introduced into inter national law.

The kingdom of Italy, which had thus been formed in viola tion of the treaties and by revolutionary means, was condemned by the Pope and was at first recognized by England alone of all the Powers. The Liberal British cabinet had recognized the right of a people to overthrow tyrannical government, and from this time dates the permanent friendship between Italy and England. Napoleon, who feared to arouse the dislike of the French Catholics by withdrawing his troops from Rome, vainly endeavoured to reconcile the pope with the king, but his policy inspired among Italians a dislike for France who had been the opponent of Italian unity.

Bismarck.

William, who had been king of Prussia since 1861 had undertaken the task of strengthening the Prussian army, and for this purpose had engaged in a conflict with the elective Cham ber, who had refused him military credits in the name of the Constitution of 185o. Having failed to find ministers who would undertake the task of governing without the support of a legal budget, William was on the point of abdicating. His son Frederick, whose wife was the daughter of Queen Victoria, was ready to ac knowledge the right of the Chamber and if he had been in the place of his father he would have permitted Prussia to evolve parliamentary government on the English model. But William at last found a minister who was prepared to govern in face of the Chamber. In 1862 Bismarck (q.v.) took control of the foreign policy of Prussia and immediately declared that German unity was only to be won "by blood and iron." Poland.—The Poles who had revolted against the tsar appealed to the great Powers. England protested in the name of the treaties of 1815 and, in agreement with France and Austria, sent Russia three successive notes in 1863, in which she asked for an amnesty on their behalf and a change in the administration of Poland. Alexander was furious and threatened to make war upon Austria. Bismarck took advantage of the opportunity to sign a military convention with Russia, on Feb. 8, 1863, which had for its object a common action on the part of the Russian and Prussian armies against the Poles. Thus Prussia won the gratitude of Alexander and the benevolent neutrality of Russia during all the wars in which she was subsequently engaged.

The Danish War 1864.

The Schleswig-Holstein question (q.v.) which had become acute in 1848 with the revolt of the Germans in Holstein, was temporarily suspended by the Treaty of London of 1852 which guaranteed the possession of the duchies to the king of Denmark. It was re-opened when Christian IX., the heir in the female line, became king of Denmark in 1863 and was compelled by a national Danish party to annex Schleswig. Frederick of Augustenburg, of the male line, was recognized heir to the duchies by the German diet. Prussia and Austria separated themselves from the other German States, protested in the name of the Treaty of London against the annexation of Schleswig, and then made war against Denmark in 1864. The British Government proposed intervention to Napoleon, but Napoleon in return asked what support England was prepared to give to France should the latter be attacked on the Rhine. England took advantage of an armistice to assemble a conference of the Powers in London, but she was unable to obtain agreement for a plan of partitioning Schleswig, and the war ended with the cession of the duchies. Bismarck having failed to obtain them for Prussia sought to im pose on the duke of Augustenburg conditions that would have rendered him a minion of Prussia, while Austria protested that the Confederation could only admit equal and independent princes.

The Austro-Prussian War.

Prussia was determined on war and Bismarck went to Biarritz to satisfy himself as to what Na poleon's attitude would be. Next he concluded a treaty of offensive alliance in 1866 with Italy. The public rupture with Austria arose from the administration of the duchies. The leading German States took the side of Austria and the rest remained neutral. War was decided with a rapidity that disconcerted all the govern ments of Europe by the single battle of Koniggratz. At the re quest of Austria Napoleon offered to mediate but he was not strong enough to frighten Prussia and was compelled to accept the peace proposals of Bismarck. By the Peace of Prague, Aus tria suffered no territorial loss but was compelled to give Prussia a free hand in Germany. Prussia annexed the German States lying between its western provinces and the main body of the kingdom. All the German States were united into a North Ger man Confederation with the exception of the four south of the Main. The duchies were annexed to Prussia with the proviso that the districts north of Schleswig should be returned to Denmark if the population expressed the wish to that effect. This clause which was abrogated in 1878, was carried out in 1920.

Napoleon's Mistakes.

Bismarck had let Napoleon hope for certain territories in compensation for the aggrandisement of Prus sia. Napoleon at first demanded the Bavarian lands on the left bank of the Rhine and then Belgium. Bismarck gave him nothing, but revealed these proposals in 1866 to the South German States to induce them to conclude treaties of alliance, and in 187o he made them public so as to arouse indignation in Belgium and Eng land against France. In 1867 Napoleon entered into negotiations with the king of the Netherlands for the purchase of the grand duchy of Luxembourg where Prussia kept a garrison in the federal fortress. Bismarck made no opposition, but on the project becom ing known he made a speech in the Reichstag which forced the king of the Netherlands to withdraw his consent, and the grand duchy was neutralized under the collective guarantee of the Powers.Napoleon was compelled to send troops into Italy to help the pope who had been attacked by the Garibaldians. The French, armed with the new rifle (Chassepot), routed the Garibaldians at Mentana (Nov. 3, 1867), and, to inspire confidence in the weapon the Government published the report of the French commander in which occurred the phrase "Les chassepots ont fait merveille," while in the chamber of deputies one of the ministers, Rouher, declared that Italy should never be allowed to enter Rome. These two phrases aroused among the Italians a hatred against France which has ever since embittered the relations between the two nations.

In France, the Government sought to prevent the unity of Germany and spoke of avenging Sadowa on a Prussia that threat ened her supremacy. Napoleon sought a rapprochement with Aus tria where the Ministry for Foreign Affairs had been entrusted to an enemy of Prussia, Beust, a former minister of Saxony. Na poleon proposed to Austria and to Italy an alliance which would restore Austria to her former position in Germany, and the ne gotiations resulted in an exchange of autograph letters between the three sovereigns in which they proclaimed their intention of holding to the idea of a triple alliance which should strengthen the peace of Europe (1869) . The archduke Albert was sent to Paris, and the French General Lebrun to Vienna, to arrange a plan of campaign against Prussia (1870). The new French ministry which came into power on Jan. 2, 187o, proposed to ensure peace by a reduction of armaments, but when England transmitted the pro posal to Berlin, Bismarck declared that it was incompatible with Prussian military law.

The Workers' International.

While accord between govern ments was broken by a succession of wars, a profound transforma tion in the conditions of industrial life prepared the way for a rapprochement of a new nature between the peoples. The progress due to science increased, in an unprecedented manner, the produc tivity of industry and the activity of commerce. Europe became covered with a network of railways and telegraphs which rendered communications and transport far quicker and less costly. Eng land took the lead in this new movement and surpassed Europe in wealth, density of population and industrial experiments, and gave the example of free trade and commercial treaties which stimulated international commerce. The first international indus trial exhibition was opened in London in 1851. The exhibition in London in 1862 brought representatives from French working classes and the leaders of English trade unionism together. They were of one mind in wishing to extend throughout Europe the labour association, on lines which had already been tested in Eng land. In 1864 the International Working Men's Association (see INTERNATIONAL) was founded in London by an assembly attended by delegates from Britain, France, Germany, Poland, Italy, etc. The rules were drafted by Karl Marx. It was organized as a fed eration, and held annual congresses, generally in Switzerland or Belgium.

The Franco-German War.

The -war between France and Prussia broke out suddenly as the result of an unforeseen incident. Bismarck, at the instigation of King William, worked in secret to secure the election of a Hohenzollern prince to the throne of Spain. When the scheme came to light the French minister for foreign affairs, Gramont, declared that France would never allow a Hohenzollern on the throne of Charles V. The French ambas sador, Benedetti, finding nobody at Berlin able to answer him, was sent by Gramont to importune King William at Ems, where he was taking the waters, and try to make him declare that he disapproved of the candidature of the prince. When the prince's father had withdrawn his candidature, Gramont, being mistrustful of Bismarck, asked the king to promise that he would never again authorize this candidature. William refused to enter into any such engagement, and put an end to the irregular negotiation by telling Benedetti that he considered the incident was at an end. The "Ems telegram" whereby William authorized Bismarck to communicate his refusal to the press, gave him the chance to an nounce the refusal of the king in a shortened form in a semi official journal, and to allow France to regard herself as having been insulted. France declared war on Prussia. The South German States joined Prussia with whom they were allied by treaty; Aus tria and Italy declared themselves neutral; the tsar maintained a benevolent neutrality towards Prussia.The issue of the war was quickly decided by the three battles round Metz, which resulted in the confinement of the main French army in Metz, and the French defeat was completed by the capit ulation of her last army at Sedan. The republican revolution of Sept. 4, 187o, in Paris, created the "Government of National Defence," which put Paris in a state of defence, and created armies in order to attempt to raise the siege.

Italy took advantage of the withdrawal of the French troops to occupy Rome on Sept. 20. The South German States entered into the federation which took the name of the German Reich; the king of Prussia was proclaimed German emperor in the palace of Versailles, Jan. 18, 1871. The war came to an end with the sur render of Paris on Jan. 28. The Peace of Frankfurt, May 1 o, ceded to Germany Alsace and part of Lorraine, which were an nexed to the German empire, in spite of two protests on the part of the elected representatives of the country, in 1871 to the French National Assembly and in 1874 to the German Reichstag. (See