United States Fisheries

UNITED STATES FISHERIES The United States fisheries supporting a large manufacturing trade are prosecuted on the seaboard of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, in the Great Lakes and in many prolific rivers. Their range extends from Alaska south-eastwards to Florida and over some thing more than ioo° of longitude. Although in respect neither of latitude nor of longitude is their range much greater than that covered by the ubiquitous steam trawlers of Great Britain, their variety is so great that no summary account can do justice to it. For details, reference must be made to the reports of the individual States and of the bureau of fisheries, which is attached to the Department of Commerce.

The value and importance of the industry increases steadily with growing recognition and increasing demand ; but there is as yet a lack of such detailed and comprehensive statistics as are essential to an accurate economic survey of the industry. The importance of such statistics is, however, now fully recognized: it was emphasised again and again at a conference of the division of scientific inquiry organised in Jan., 1927, by the bureau of fisheries, and great progress has been made in recent years through the efforts of the bureau to make good the deficiency.

It is calculated that the fisheries and fishery industries of the United States (including whale, sponge and other fisheries, which it is difficult to extract) employ about 190,00o persons, and that the property and equipment involved in them is worth more than $210,000,000. The quantity of fishery products sold by fishermen is over 1,300,000 tons, valued at nearly $109,000,000. Of the manufactured fish products the most important are : (1) Canned products, over $86,000,000 worth, the chief of which are salmon, over $56,000,000 worth, and sardines, about $14,500,000.

(2) Fish oils, 10,900,000 gallons, valued at something more than $5,000,000. Of these, the most important are menhaden, about 4,000,00o gallons; herring, over 3,000,00o gallons, and sar dine, over 2,000,000 gallons.

(3) Fish meal, about 93,00o tons, valued at about $3,650,000.

(4) Fish glue, 520,600 gallons, valued at about $732,000.

(5) Poultry grit, about 251,00o tons, valued at $2,400,000. The most important sea fisheries are those centred on the three ports of Boston and Gloucester, Mass., and Portland, Me. These fisheries employ 35o sail, steam and oil-driven vessels, includ ing 3o steam trawlers. The aggregate landings of the three ports are about 106,50o tons and their value over $9,000,000. The three most important fishes are haddock, about 42,000 tons; cod, about 35,000 tons; and mackerel, about 16,00o tons. In 1926, the year to which the above figures belong, about 26% of the catch was taken by steam trawlers ; again, 83% was taken off the coast of the United States, 16% off that of Canada, and I% on the banks of Newfoundland.

It is said that over 90% of the sea fish landed in American ports is consumed within 200 miles of the coast. It is, however, generally anticipated that, as the result of the improvement of methods of transport, by means of which it is hoped to bring sea fish within reach of consumers far inland, there will, in the near future, be a great development of sea fishing, and especially of trawling. The tendency at present is to rely mainly on vessels of comparatively small tonnage—not more than 1 oo tons—using oil engines of diesel or semi-diesel type. If the development of the markets is as great as is expected in some quarters, it seems probable that steam trawling may also develop.

The lobster fisheries, which have long suffered from the results of indiscreet exploitation, are still one of the important branches of the fishing industry of the New England States and particularly of the State of Maine.

The first value of the fisheries of the States of the Pacific Coast is (figures based on statistics for 1925) about $24,500,000. The landings of fish, other than shell-fish, are about 266,000 tons, and of shellfish about 5,600 tons. By far the most valuable fishery is that for salmon, yielding over 62,00o tons, with a value of over $10,000,000. Next in importance is the tuna fishery of some 24,000 tons, with a value of about $4,500,000. The halibut fishery, centred at Seattle but prosecuted from California northward, is next in importance. The landings amount to between 8,000 and 9,000 tons, and the value to about $2,177,000. These figures do not include something over x,000 tons landed in Alaska. The sardine fisheries, valued at about $2,000,000 are fourth in impor tance, though the yield of these fisheries, about 140,000 tons, is greatly in excess of all the rest.

The oyster fisheries of the United States exceed by a consider able margin those of the rest of the world. The chief producing States are Maryland and Virginia. Maryland, in 188o, the high est recorded year, produced over 10,000,00o bushels, valued at 5 million dollars, and, in 1915, the lowest recorded year, over 4,000,000 bushels, valued at 3+ million dollars. The output of Virginia in 1925 was 4,300,000 bushels, valued at over 2i million dollars. The highest previous record of this State (19o4) was 7,600,00o bushels, valued at more than 31 million dollars. Other States producing over 1,0oo,000 bushels annually are New York, New Jersey, Mississippi and Louisiana.

The fisheries of the Great Lakes are shared between the United States and Canada, the catch of the former being about double that of the latter. The United States landings from the lakes in 1925 amounted to nearly 31,000 tons; in the highest recorded year, 1915, the landings exceeded 48,00o tons. Over 4, coo tons of lake trout were landed in 1925, of which more than 3,00o tons came from Lake Michigan. The landings of white fish (Coregonus clupeiformis) were 1,50o tons, chiefly from lakes Michigan and Huron. The heaviest landings were those of lake herring, 6,5oo tons, of which about 6o% was taken in Lake Superior and nearly 3o% from Lake Michigan. Blue pike, 4,70o tons, are taken almost exclusively in Lake Erie. Sturgeon have varied between 48 tons in 1915 and i t tons in 1925.

The most important anadromous fishes, other than salmon, are shad, alewives and striped bass. The shad fisheries of the Potomac yielded in 1926 over 46o tons, valued at $217,000, and, in 1922, the highest previously recorded year, nearly 1,400 tons. The landings from the Hudson river are, roughly, a quarter of those of the Potomac. The landings of alewives from the Potomac (1926) were 2,500 tons, valued at $55,000. In the highest pre viously recorded year (1909) these landings were more than doubled.

The striped bass is fished all along the Atlantic coast of the States, and, like the shad, has been successfully naturalized on the Pacific coast.

The administration of the fisheries is in the hands of the various States, but the bureau of fisheries at Washington, which is attached to the Department of Commerce, not only conducts scien tific investigations, either independently or in co-operation with provincial investigators, but has acted as a clearing-house for statistical information collected within the States, largely at its instigation. Only the State Governments have authority to en force the collection of statistical records, and the function of the bureau is, in this respect, chiefly one of advice, co-ordination and compilation. It is through the bureau also that the United States is represented in the North American Committee of Fishery Investigations. The bureau publishes annual reports on the fishing industries of the United States, including steadily improving sta tistical material, and Reports on the Progress of Biological Studies, which give a general picture of investigations conducted and of their results. Nor are the investigations of the bureau confined to purely biological studies. They embrace important investiga tions of the technique of handling fish after capture, and the bureau has played an important part in the recent development of the "package fish" trade.

The attention of the bureau has also been directed to improving the method of production of such fishery products as oil, meal and manure, with a view to eliminating waste, more especially in connection with the menhaden industry and with the disposal of the waste from filleting and canning. The investigations of the bureau embrace also such subjects as the preservation of nets, the canning of sardines and inquiries as to the nutritive value of fish.

The prospect of very considerably increasing by artificial means the stocks of those multitudinous fishes which are the foundation of the great commercial fisheries of to-day is at present remote. There is no reason to discourage researches directed to the arti ficial propagation of fish of every kind, but for the present the more practical line of inquiry will be that which aims rather at the prevention of wasteful exploitation than at artificial contributions to the stock.

Certain fishes lend themselves to the art of pisciculture, more or less according to circumstances. Among freshwater fishes those of the carp family can be successfully bred and reared in cap tivity, and trout can be profitably hatched in special receptacles and reared in suitable ponds to the yearling or two-year-old stage, or even further, to be disposed of either for stocking or restock ing sporting waters or for consumption in hotels and restaurants. The process is comparatively simple. Usually the ripe female fish are "stripped," the eggs being allowed to fall into a vessel of water into which a little milt from the male is introduced, the eggs thus fertilized being then transferred to the hatching receptacles. The same process can be applied to sea fishes, and experiments have been carried out in the distribution of newly hatched larvae of plaice and cod in waters where it is desired to increase the stock ; but there is no convincing evidence in the case of these fishes that the result sought has in any case been achieved. The great fecundity of sea fishes is nature's provision against an enormously high rate of mortality, and the number of larvae which it is practicable to hatch in a hatchery of reasonable size is so small by comparison with the natural distribution that it is inherently improbable that the output of a hatchery could make an appreciable difference in the abundance of the stock. The investigations undertaken by Captain Dannevig in selected Nor wegian fjords in 1904 and 19o5 tend to confirm this conclusion. (See Report for rgo6 of the Lancashire Sea-fisheries Laboratory, Liverpool, 1907.) A possible exception may be found in the results of the work of the Commission on Inland Fisheries in the artificial rearing of young lobsters from the egg to the lobsterling stage in the quiet waters of Rhode Island, U.S.A. There appears to be some evidence of improvement of the lobster fisheries re sulting from this work, but whether the improvement is to be attributed to this cause or to such methods of conservation as, e.g., protection of the berried female, and whether in the former case the improvement has been proportionate to the cost involved, is open to some doubt. (See Annual Reports of the Commis sioners of Inland Fisheries, Rhode Island, especially those for 1908 [Special paper by A. O. Mead] and 191 o [Appendix].) Artificial methods of cultivation have chiefly proved useful where it has been desired to populate streams or parts of streams which are understocked, or to introduce into a river a new species of fish. The distribution of eyed ova or of yearling fry of trout or salmon in waters inaccessible to native fish may lead to the establishment of a stock or to the increase of the total run of salmon in a river. The shad has been successfully acclimatized in the rivers of California and in the Mississippi by the distribution of artificially propagated eggs from the eastern rivers of the United States. The quinnat and Atlantic salmon and the brown and rainbow trout have by similar means been successfully naturalized in the rivers of New Zealand. Experiments which have been carried out in certain British rivers for the purpose of improving the native stock of salmon by the introduction of fresh blood by crossing with the stock of other rivers by means of arti ficial fertilization of the eggs have hitherto been inconclusive.

There is another branch of pisciculture which may be broadly summed up as transplantation. This method is familiar to every oyster planter and is usefully employed in the cultivation of other molluscs, such as cockles, mussels, etc. The main purposes of transplantation of molluscs are to relieve over-crowding of young fish and to place the mature fish on beds where the conditions are suitable for fattening. Transplantation is an essential feature of successful oyster farming (see OYSTER) .

Successful results have attended the transplantation of eels. Millions of elvers are annually captured in the river Severn and exported to Germany for distribution in suitable waters in that country. Similarly elvers are trapped in the Danish fjords and transplanted to suitable lagoons to become the source of a profit able industry.

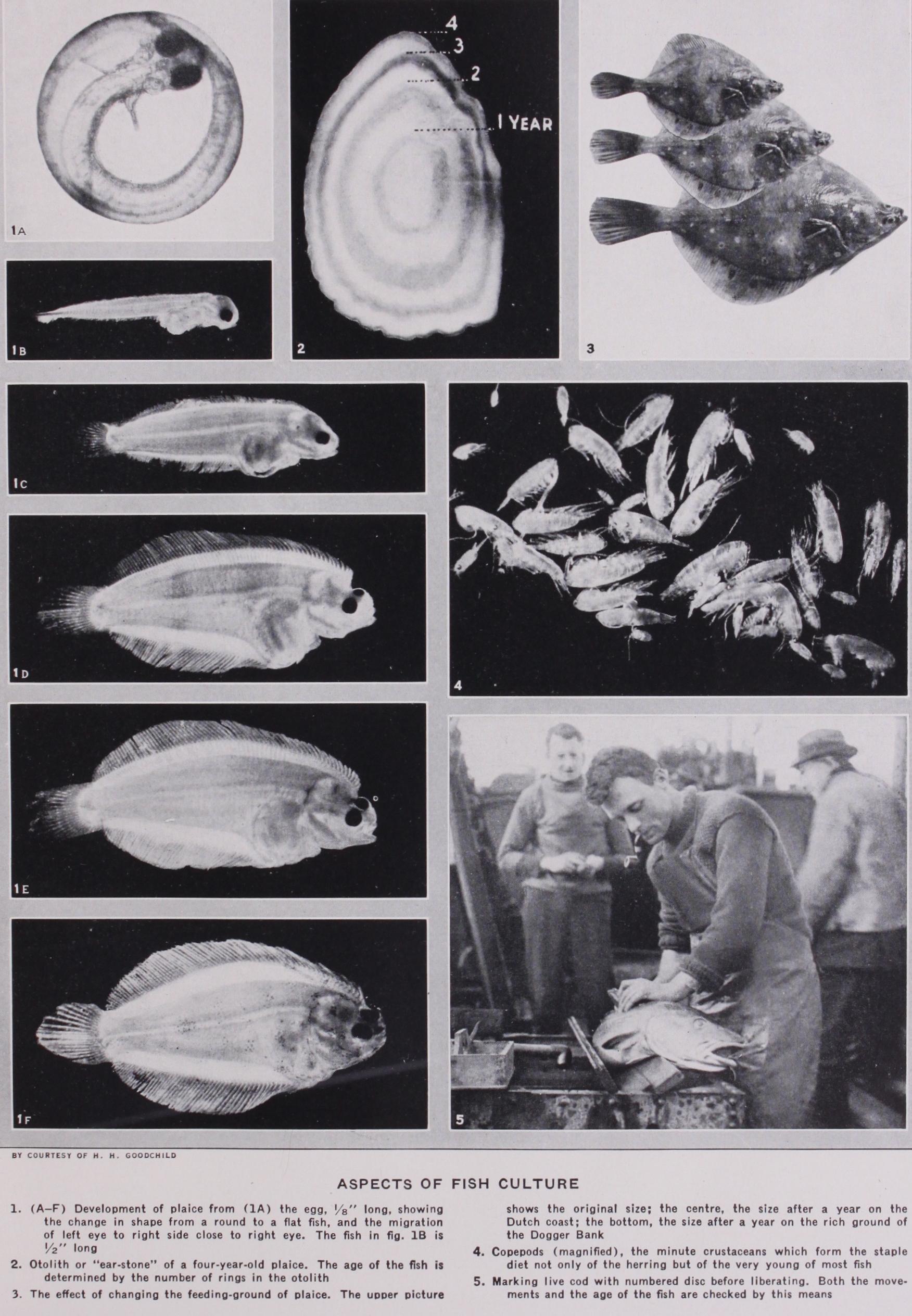

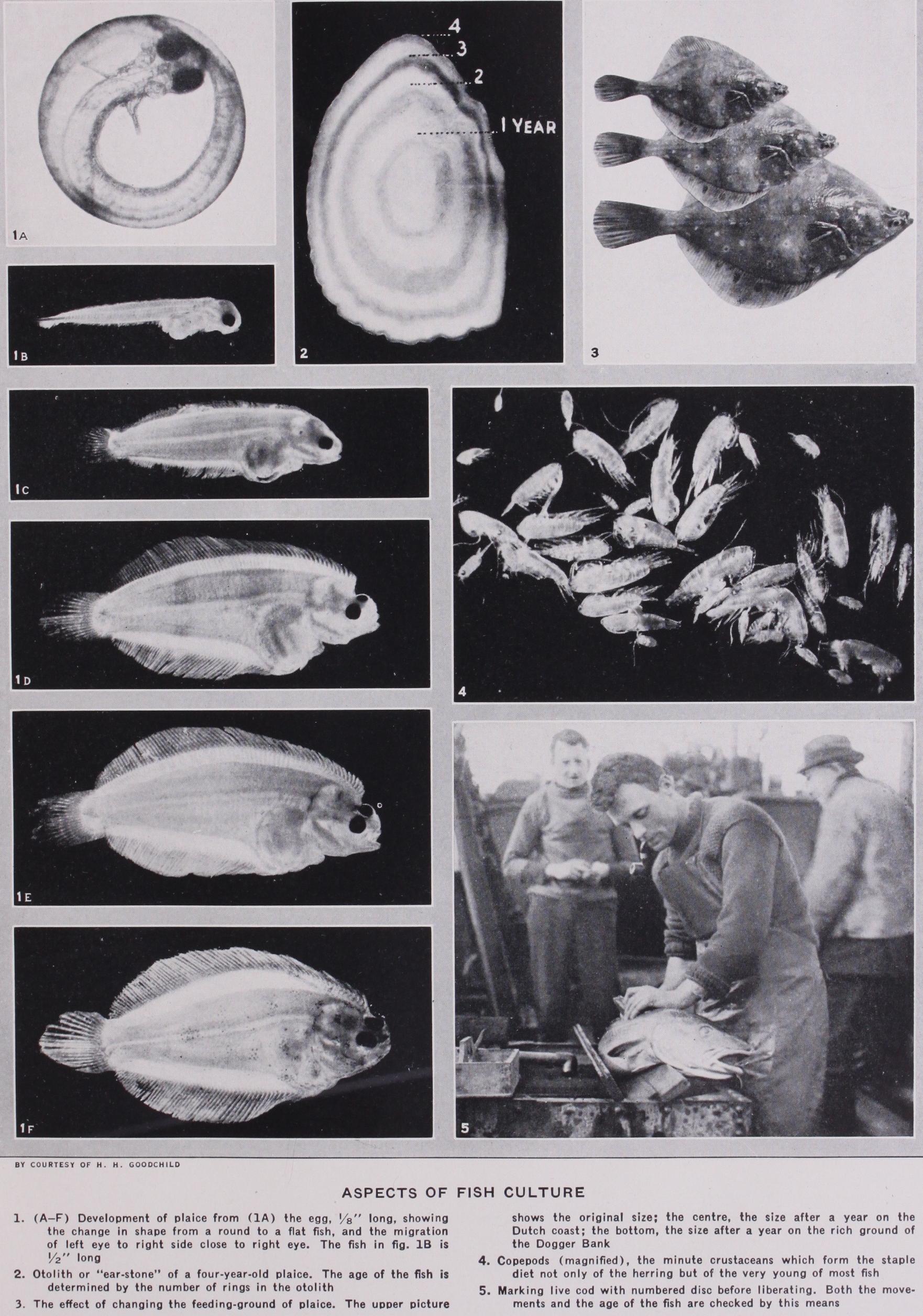

Reference is made below to the rapid growth of plaice trans planted from the eastern waters of the North Sea to the Dogger Bank, and similar experiments in the transplantation of plaice from the outer lagoons of the Limfjord in Denmark to the inner, which are rich in food hut are blocked against the immigration of flat fish by dense growths of sea grass (Zostera), have laid the foundations of a profitable fishery in these waters.

So far as experience goes, then, it is clear that attempts to increase the supply of sea fish by artificial hatching have been unsuccessful, that the increase of the stock by transplantation succeeds in the case of molluscs and in the case of flat fish in special circumstances, such as those appertaining in the Danish fjords, and may prove successful with certain fishes in more open waters. Artificial propagation from the egg is useful for the introduction of a new stock of fish in suitable river waters either by the distribution of eyed ova or, where that is impracticable, by the distribution of young fish which have reached an age at which they can take care of themselves. It is extremely doubtful whether it is ever worth while to distribute the newly hatched larvae, which are very delicate and are exposed on distribution in the open waters of a stream or of the sea to a thousand hazards.

Scientific Research.—Speaking of the inaugural meeting of the International Fisheries Exhibition of 1883, T. H. Huxley said, "I believe that the cod fishery, the herring fishery, the pilchard fishery, the mackerel fishery, and probably all the great sea-fisheries are inexhaustible ; that is to say that nothing we do seriously affects the number of fish." In an earlier passage of his argument, which was, in effect, that the fish were so prodigiously numerous and the quantity caught by man so insignificant by comparison with the other destructive agencies at work that regulation of man's operations would be futile, he qualified his conclusion with the words, "in relation to our present method of fishing." In 1883 the use of steam power for fishing was hardly regarded seriously (the first experiment was made in 1877 with an old paddle tug out of North Shields), the otter trawl had not been invented, and the carefully designed steam trawler of to-day had not been dreamed of. Every innovation is an object of sus picion, especially among such conservative folk as fishermen are and Huxley was familiar with the complaints laid against the beam trawl before the royal commission of 1864 of which he was a member. The circumstances of to-day are very different and, whatever view may be taken of the controversial topic of over fishing no one is now likely, with full knowledge of the evidence, to say that the operations of man are insignificant in their effects upon the composition of the stock of fish.

The Exhibition of 1883 gave impetus to a demand for scientific investigation of the sea and its resources which had already made itself felt. Ten years had passed since the "Challenger" sailed on her famous voyage. The Fishery board for Scotland had just be gun systematic inquiries; abroad, notably in Germany, marine science was establishing itself and in Great Britain the next year was to witness the establishment of the Marine Biological Associa tion of the United Kingdom. With the rapid development of fish ing which followed the introduction of steam and, later (about 1895) of the otter trawl the old apprehensions were intensified and compelled the serious attention of the Governments, so that, when in 1899 the king of Sweden invited representatives of the countries interested in the fisheries of the North sea and the Baltic to a conference at Stockholm to discuss the subject of co-operation in the study of marine problems the response was general and, after a second conference in Christiania in 1901, the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea was constituted to co ordinate the national researches of the participating countries. To-day all the countries of Northern Europe with important fishing interests are members of the Council, except Soviet Russia. Por tugal, Spain and Italy are also members, having joined respec tively in 1922, 1924 and 1927, and the Council's investigations cover the whole of the continental shelf of Europe and Northern Africa outside the Mediterranean.

In 1919 there was established the Commission Internationale pour l'Exploration de la Mer Mediterrannae, fashioned in many respects on the model of the International Council, and in 1921 an analogous body was formed under the name of the North Ameri can Committee on Fishery Investigations to secure co-ordination of marine fishery investigations between the United States of America, Canada, Newfoundland and France.

The aim of economic marine biology is well summed up in the object set before it by the International Council for the Ex ploration of the Sea, which is "the rational exploitation of the sea." To exploit the sea rationally means, presumably, to get as much out of it as is possible at the least possible cost and without waste.

The first necessity is to know or at least to have a rational conception of what the stock of fish is and what are the factors governing these fluctuations of it which have puzzled and alarmed generations of fishermen. The first step in any such inquiry must take the form of statistics. The most complete and comprehensive statistics of sea fisheries are those of Great Britain. The Inter national Council, which publishes an annual Statistical Bulletin, realises the importance of uniformity of method in the collection and presentation of statistics and is disposed to accept the British method as its model: hut few of the constituent countries are, as yet, as well equipped as Great Britain for their collection. The British statistics record annually the total landings of fish and of each of the most important food fishes separately. Such statis tics are mainly of use for commercial purposes. The details re quired to supplement and guide biological investigations are many. The endeavour is made, in the case of each important food fish, to show from year to year the weight of fish taken, the range of size of the most important species the region in which they are taken, and the fishing power expended in their capture. Note is taken of the proportions of the different trade categories in the landings—"large," "medium" and "small"; but as these are vari able dimensions, a check is kept upon these variations by meas urers at the principal ports. Increased landings from any region may be the result merely of increased fishing: therefore note is taken of the number of voyages made and the length of time spent in fishing, from which is calculated the quantity of fish landed per day's absence from port, or, more lately, per i oo hours' fishing. Allowance has to be made, as well as may be, for increased size and power of the ships fishing, and for increasingly efficient gear. Having thus ascertained, as nearly as possible, the quantities of fish, in their different species, landed in a given period in different regions, the relation of this quantity to the power expended in its capture and the quality of the landings as regard the proportion of the totals falling into certain size cate gories, the calculations are further checked by special statistics collected on board a certain number of trawlers by fish measurers. The fish measurer takes mixed samples of the contents of the trawl after each haul and measures every fish in the sample. A considerable quantity of the fish taken are too small to be market able, and are thrown overboard: but, since they are usually killed in the process of capture, they are lost to the stock. It is the business of the fish measurer to complete the picture furnished by the port statistics by revealing the quantity of undersized fish not landed, but, nevertheless, taken out of the total available stock. The actual stock on which we are working can never be accurately known: but the data collected by the methods just enumerated enable a reasoned opinion to be formed as to whether, making due allowance for all other factors, the stock is being overfished.

The chart on page 294 illustrates generally the method of comparison of landings with fishing power.

The chart presents two interesting features. The first is the similarity between the ascending curves of landings and of steam power employed until two new factors, the general adoption of the otter trawl and the development of fishing on the more distant grounds appear to be reflected in a steep rise of the curve of land ings. The second is the high point at which the interrupted curve of catch per day's absence from port starts immediately after the war, during which little fishing had taken place, and its rapid decline apparently reflecting the influence of renewed fishing.

The following table of the landings of North Sea plaice is an interesting illustration of what appears to be the effect of fishing operations on the composition of the stock of a single species of fish.

The graph and the table are to be regarded merely as samples of the statistical data by means of which the endeavour is made to record changes of the stock (which, in the nature of things can, at best, only be estimated) and to form a reasoned opinion as to the relation between these fluctuations arid the operations of men.

Such statistical data are the starting point of biological investi gations and may furnish the test of provisional biological con clusions. In order that all factors affecting the stock of fish may he taken into account, it is necessary to study the life histories of the food fishes severally and collectively. Since the life histories of fishes, as of other animals, must be governed mainly by the factors of their environment, that environment must also be studied. The most important factors of the environment are, to express it very generally, climate and food, the former naturally reacting to a great degree upon the latter. What corresponds to climate in the sea is—again speaking in general terms—the physicochemical composition and the movements of the water. It is an established fact that all animal organisms depend ulti mately for their food supply in the sea, as on land, upon plant life.

The fixed sea-weeds are found only in a narrow fringe in shallow water round the coasts, but in the upper water layers of the whole ocean to such depths as sunlight can penetrate are multi tudes of microscopic plants, upon which above all depends the great productivity of the sea. These plants are eaten by various animals, which in their turn are eaten by larger ones, till at the other end of the food chain we find the fishes exploited by man, which thus ultimately depend upon vegetable growth. The plant harvest of the sea depends on many physical and chemical factors, the most important being suitable temperatures, an adequate sup ply of sunlight, of carbonic acid and of certain chemical salts.

Thus, fishery research is divided broadly into four branches,— statistics, to which we have already referred, investigations of fishes; investigations of their food, including both the organisms, many of them microscopic, inhabiting the surface layers of the water and the invertebrates found at the bottom of the sea; and hydrographical investigations. In practically every instance con clusions have to be deduced from samples collected by ingeniously contrived, but as yet imperfect instruments. The factors to be taken into account are, moreover, so numerous and so complex and the area of inquiry so wide that the only hope of arriving at well-founded conclusions within a measurable space of time lies in organized team work. This fact has been recognized by the Gov ernments of States represented in the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea in making themselves individually responsible for definite shares of a programme of work interna tionally organised through the Council. Neither must it be for gotten that the deep sea fisheries are for the most part prosecuted in waters in which all countries have equal rights of fishing. If, therefore, any practical results are to ensue from the knowledge acquired, in the form of regulation of fishing operations, or, as is not wholly inconceivable, actual cultivation of the stock, these measures must be applied with the goodwill and co-operation of all the interested countries.

A detail of the study of the life history of fishes of peculiar economic importance is the investigation of the rate of their growth and the variations of the rate of growth responding to different circumstances. For this purpose it is essential to have an index of age so that the growth rate of fishes of the same ages in different localities and circumstances and the variation of the growth rate generally at different stages of life or in favourable or unfavourable years may be compared. The ages of some fishes —notably of flat fishes—are fixed by counting the annual rings in the ear bones or otoliths, of others—notably the herring—by counting similar rings in the scales. The technique of scale read ing is by no means simple, and in the case of cod considerable difficulty has been experienced in accurate deductions of age from the scales.

Again, it is necessary to study the food of fishes by examination of the contents of the stomachs, and to correlate the information thus gained with information as to the distribution and abun dance, from time to time of various organisms, pelagic or de mersal, which furnish the food of different fishes or of the same fishes at different stages of life. That an adequate supply of suit able food is essential to healthy growth is axiomatic, and it has been suggested that the present rate of destruction of small fish might advisedly be accelerated in order to promote the more rapid growth of the survivors. This raises the question of the amount of food which fishes can, at different stages of life, usefully consume. It may, however, be remarked that, if it were true, as appears to be established by evidence laid before the royal commission of 1864, that it was then by no means uncommon for a sailing smack, working on the most frequented (admittedly also the richest) grounds of the North sea to take from two to three tons weight of fish in a three hours haul with a beam trawl, whereas to-day the average daily take of a North Sea trawler using the otter trawl is something less than a ton, there seems, prima facie to be little cause to apprehend that the food supplies are, under present con ditions, overtaxed.

It is also necessary to follow the migrations of the fishes, which can be most directly done, where such a course is practicable, by marking large numbers of them and offering rewards for well au thenticated information as to the time and locality of their re covery. The technique of fish marking still requires elaboration, and is being carefully studied.

Some or all of these various methods of investigation have been applied and are being applied to the most important of the food fishes in accordance with programmes laid down by the Inter national Council for the Exploration of the Sea. Those which have been most intensively investigated to date are the plaice and the herring, but investigation has also made considerable progress in regard to cod, haddock and hake, while other fish have received or are receiving attention as opportunity serves.

A classical example of the study of growth rate is that carried out in connection with the investigations of the plaice fisheries, where, by marking large numbers of young plaice, 7 to 8 in. long, taken in the shallow waters on the east side of the North sea, transplanting a proportion of them to the Dogger bank, where there is an abundance of suitable food, and leaving others where they were caught, it was proved that the transplanted fish devel oped at a remarkably greater rate than those left behind. The former, in 12 months grew about 5 in. in length and to nearly four times their original weight, while the latter grew little more than 2 in. in length and no more than doubled their weight.

An interesting illustration of deductions from scale reading is furnished by the investigations of Johan Hjort of the Norwegian herring fisheries, by means of which he showed that frequently and, indeed, usually, fish of a certain year group predominated over all other year groups over a series of years, whence it ap peared reasonable to deduce that the stock of herrings from year to year depended mainly not upon regular annual accretions, but rather upon occasional floods from particularly prolific years. Hjort's examination of samples of Norwegian spring herrings in the seven years 1907-1913 revealed the presence of the following percentage of herrings of the 1904 year class:—I.6, 43.7, 77.3, 70.0, The most important examples of the study of the migrations of fish by marking are the experiments with marked fish con ducted in connection with the plaice investigations, mentioned above and those with marked cod carried out by Hjort and re ported in his Fluctuations in the Great Fisheries of Northern Europe ; while a notable example of the study of migration by other means than marking is furnished by Schmidt's investigations of the eel, in the course of which, by following the larval eels, he traced the European eels to their spawning place in the Sargasso sea.

The hydrographical investigations take the form not only of the study of the physicochemical composition (and temperature) of the sea, upon which depends the harvest of the plant growth which, as already observed, is the beginning of the chain of marine life, but also of the movements of the water at the surface, near the bottom and in the intermediate layers, which govern to a great degree the actual distribution of the stock of fish particularly in the larval stages. For these purposes various ingenious instru ments have been contrived and are constantly being improved upon ; water bottles for the collection of samples at known depths, self-recording current meters, drift bottles adjusted to float at or near the surface, or to trail along the sea bottom. By means of such instruments and by many and various lines of investigation a few of which only it has been feasible to indicate above, the en deavour is being made to probe the mysteries of life in the sea.

The Government of Great Britain while taking direct responsi bility, through the Fishery Board for Scotland and the Fisheries Department of the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, for economic investigations, most of which are carried out in co operation with the International Council, supports by liberal grants unofficial institutions devoted to marine research, on no other condition than that their work shall be of such a standard of excellence as to make it worthy of support. The chief of such institutions are the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, with its headquarters and laboratory at Plymouth ; the Dove Marine laboratory at Cullercoats, the oceanographical de partment of the University of Liverpool and the Scottish Marine Biological laboratory at Millport (see MARINE BIOLOGY).

The organization of fishery research varies from the country to country, but it can be stated in general terms that in practically every country of Europe provision is made for such researches in a greater or less degree, and with a greater or less measure of Government support; that in the United States of America the provision for fishery investigations partly under the direction of the States, partly under that of the central Government, is elabor ate and costly; that in varying degree of development corres ponding inquiries are in progress in most of the British domin ions and colonies, and, indeed, in every country in which the economic importance of fisheries has gained recognition.

To pass under review the investigations of the last quarter of a century and their results up to date would be a gigantic task. No more has been possible here than to indicate briefly some of the lines of investigation and their aim.

The uses of science do not end with those studies which bear upon the capture of fish. The art and science of catching fish has developed far more rapidly than that of the disposal of fish when caught. The problem of keeping fish taken on distant voy ages in a fresh state is not wholly solved by the use of ice. The fish which, in the course of a distant voyage go first into the hold, and, on return to port, come last out of it, are seldom fit for the fresh fish market ; the present day methods of pickling herrings are practically the same as those invented by the Dutch man Beukels in the 17th century; the methods of production of fish oils are, as yet, imperfect. In almost every phase of the handling and use of fish there is work for the biochemist and in recent years the problem of how to make the best use of the fish when caught has been the subject of serious scientific study. Considerable progress has been made in devising methods of re frigeration suitable for application to fish, but there are many technical obstacles to be overcome. It is enough for the present to point out that the future development of the industry will de pend not less, perhaps more, upon the improvements that science may devise in the methods of handling fish and fish wastes than upon the discovery of new resources or of improved and more intelligent practice in the capture of the living fish.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-T.

W. Fulton, The Sovereignty of the Sea, see Bibliography.-T. W. Fulton, The Sovereignty of the Sea, see especially ch. ii.-.vi., sec. i (191I) ; J. Murray and J. Hjort, The Depths of the Ocean (1912) ; A. M. Samuel, The Herring (1918) ; J. T. Jenkins, The Sea Fisheries (192o), The Fishes of the British Isles (1925), The Herring and the Herring Fisheries (1927) ; W. E. Gibbs, in the ear bones or otoliths, of others—notably the herring—by counting similar rings in the scales. The technique of scale read ing is by no means simple, and in the case of cod considerable difficulty has been experienced in accurate deductions of age from the scales.

Again, it is necessary to study the food of fishes by examination of the contents of the stomachs, and to correlate the information thus gained with information as to the distribution and abun dance, from time to time of various organisms, pelagic or de mersal, which furnish the food of different fishes or of the same fishes at different stages of life. That an adequate supply of suit able food is essential to healthy growth is axiomatic, and it has been suggested that the present rate of destruction of small fish might advisedly be accelerated in order to promote the more rapid growth of the survivors. This raises the question of the amount of food which fishes can, at different stages of life, usefully consume. It may, however, be remarked that, if it were true, as appears to be established by evidence laid before the royal commission of 1864, that it was then by no means uncommon for a sailing smack, working on the most frequented (admittedly also the richest) grounds of the North sea to take from two to three tons weight of fish in a three hours haul with a beam trawl, whereas to-day the average daily take of a North Sea trawler using the otter trawl is something less than a ton, there seems, prima facie to be little cause to apprehend that the food supplies are, under present con ditions, overtaxed.

It is also necessary to follow the migrations of the fishes, which can be most directly done, where such a course is practicable, by marking large numbers of them and offering rewards for well au thenticated information as to the time and locality of their re covery. The technique of fish marking still requires elaboration, and is being carefully studied.

Some or all of these various methods of investigation have been applied and are being applied to the most important of the food fishes in accordance with programmes laid down by the Inter national Council for the Exploration of the Sea. Those which have been most intensively investigated to date are the plaice and the herring, but investigation has also made considerable progress in regard to cod, haddock and hake, while other fish have received or are receiving attention as opportunity serves.

A classical example of the study of growth rate is that carried out in connection with the investigations of the plaice fisheries, where, by marking large numbers of young plaice, 7 to 8 in. long, taken in the shallow waters on the east side of the North sea, transplanting a proportion of them to the Dogger bank, where there is an abundance of suitable food, and leaving others where they were caught, it was proved that the transplanted fish devel oped at a remarkably greater rate than those left behind. The former, in i2 months grew about 5 in. in length and to nearly four times their original weight, while the latter grew little more than 2 in. in length and no more than doubled their weight.

An interesting illustration of deductions from scale reading is furnished by the investigations of Johan Hjort of the Norwegian herring fisheries, by means of which he showed that frequently and, indeed, usually, fish of a certain year group predominated over all other year groups over a series of years, whence it ap peared reasonable to deduce that the stock of herrings from year to year depended mainly not upon regular annual accretions, but rather upon occasional floods from particularly prolific years. Hjort's examination of samples of Norwegian spring herrings in the seven years 1907-1913 revealed the presence of the following percentage of herrings of the 1904 year class:-1.6, 43.7, 77.3, 70.0, The most important examples of the study of the migrations of fish by marking are the experiments with marked fish con ducted in connection with the plaice investigations, mentioned above and those with marked cod carried out by Hjort and re ported in his Fluctuations in the Great Fisheries of Northern Europe; while a notable example of the study of migration by other means than marking is furnished by Schmidt's investigations of the eel, in the course of which, by following the larval eels, he traced the European eels to their spawning place in the Sargasso sea.

The hydrographical investigations take the form not only of the study of the physicochemical composition (and temperature) of the sea, upon which depends the harvest of the plant growth which, as already observed, is the beginning of the chain of marine life, but also of the movements of the water at the surface, near the bottom and in the intermediate layers, which govern to a great degree the actual distribution of the stock of fish particularly in the larval stages. For these purposes various ingenious instru ments have been contrived and are constantly being improved upon ; water bottles for the collection of samples at known depths, self-recording current meters, drift bottles adjusted to float at or near the surface, or to trail along the sea bottom. By means of such instruments and by many and various lines of investigation a few of which only it has been feasible to indicate above, the en deavour is being made to probe the mysteries of life in the sea.

The Government of Great Britain while taking direct responsi bility, through the Fishery Board for Scotland and the Fisheries Department of the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, for economic investigations, most of which are carried out in co operation with the International Council, supports by liberal grants unofficial institutions devoted to marine research, on no other condition than that their work shall be of such a standard of excellence as to make it worthy of support. The chief of such institutions are the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, with its headquarters and laboratory at Plymouth ; the Dove Marine laboratory at Cullercoats, the oceanographical de partment of the University of Liverpool and the Scottish Marine Biological laboratory at Millport (see MARINE BIOLOGY).

The organization of fishery research varies from the country to country, but it can be stated in general terms that in practically every country of Europe provision is made for such researches in a greater or less degree, and with a greater or less measure of Government support; that in the United States of America the provision for fishery investigations partly under the direction of the States, partly under that of the central Government, is elabor ate and costly; that in varying degree of development corres ponding inquiries are in progress in most of the British domin ions and colonies, and, indeed, in every country in which the economic importance of fisheries has gained recognition.

To pass under review the investigations of the last quarter of a century and their results up to date would be a gigantic task. No more has been possible here than to indicate briefly some of the lines of investigation and their aim.

The uses of science do not end with those studies which bear upon the capture of fish. The art and science of catching fish has developed far more rapidly than that of the disposal of fish when caught. The problem of keeping fish taken on distant voy ages in a fresh state is not wholly solved by the use of ice. The fish which, in the course of a distant voyage go first into the hold, and, on return to port, come last out of it, are seldom fit for the fresh fish market ; the present day methods of pickling herrings are practically the same as those invented by the Dutch man Beukels in the I7th century ; the methods of production of fish oils are, as yet, imperfect. In almost every phase of the handling and use of fish there is work for the biochemist and in recent years the problem of how to make the best use of the fish when caught has been the subject of serious scientific study. Considerable progress has been made in devising methods of re frigeration suitable for application to but there are many technical obstacles to be overcome. It is enough for the present to point out that the future development of the industry will de pend not less, perhaps more, upon the improvements that science may devise in the methods of handling fish and fish wastes than upon the discovery of new resources or of improved and more intelligent practice in the capture of the living fish.

BIBLIOGRAPHY-T. W. Fulton, The Sovereignty of the Sea, see Bibliography-T. W. Fulton, The Sovereignty of the Sea, see especially ch. ii.—vi., sec. I (191I) ; J. Murray and J. Hjort, The Depths of the Ocean (1912) ; A. M. Samuel, The Herring (1918) ; J. T. Jenkins, The Sea Fisheries (1920), The Fishes of the British Isles (1925), The Herring and the Herring Fisheries (1927) ; W. E. Gibbs, The Fishing Industry (1922) D. K. Tressler, Marine Products of Com merce (1923) ; Sir F. Floud, The Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries last chapter (1927) ; O. W. Radcliffe, Fishing from the Earliest Times (1926) ; F. M. Davis, An Account of the Fishing Gear of England and Wales (1927), series 2, vol. ix., no. 6, of Ministry of Agricul ture and Fisheries, Fishery Investigations (1913, etc.) ; Fishery Board for Scotland, Scientific Investigations (1883, etc.) ; E. J. Allen, "A Selected Bibliography of Marine Bionomics and Fishery Investiga tions," Journal of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, nos. I, 2 of vol. i. (1926) ; Reports, International Council for the Investigation of the Sea, Statistical Bulletins, ibid.; Reports of Depart ment of Commerce (Bureau of Fisheries) , United States; Imperial Economic Committee on Marketing of Foodstuffs, Fifth Report "Fish," Cmd. 2,934 (1927) ; Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, Annual Reports on Sea Fisheries, Statistics of Sea Fisheries, Annual Reports on Salmon and Freshwater Fisheries; Fishery Board for Scotland, Annual Reports; Department of Commerce (Bureau of Fisheries), Fishing Industries of the United States (annual) ; Reports of the departments responsible for fisheries in various countries.

(H. G. M.)