the Federal Reserve System

FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM, THE, a United States banking system which began operation on Nov. 16, 1914. The system consists of 12 Federal Reserve Banks, 25 branches, two agencies, and a Government supervisory body in Washington known as the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The 12 Reserve Banks are in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Richmond, Atlanta, Chicago, St. Louis, Minneapolis, Kansas City, Dallas, San Francisco. Every Federal Reserve Bank, with its branches, serves a separate district not coterminous with State boundaries. The Reserve Banks are bankers' banks in that they perform for the banks of the United States a service similar to that which commercial banks of deposit perform for their cus tomers. They receive deposits from banks, they make loans to banks, they receive and collect checks. In addition, they have power to issue Federal Reserve notes and act as fiscal agents of the United States. In more technical language, they are banks of issue and rediscount, with somewhat similar powers to the Bank of England, the Bank of France, the Reichsbank and other Euro pean banks of issue.

Reasons for Establishment.—Although the United States was among the last of the important countries of the world to establish a bank of issue and rediscount, there is no other country where the needs for such an institution had been so thoroughly demon strated. The outstanding peculiarity of the U.S. banking system has been its large number of independent banks. Until recent years branch banking had developed hardly at all. By 1914 as many as 27,000 independent banks had been organized, each operated by its own local board of directors and its own separate official staff and each carrying its cash reserve in its own vaults, or in the vaults of other similar banks in large cities. Not only was there this large number of independent banks, but they dif fered greatly in powers, size and character. About 7,500 of them were national banks, incorporated under laws of the U.S. Govern ment and supervised by the comptroller of the currency, who is a Federal political officer. The others were all created pursuant to the laws of the several States of the Union governing the estab lishment of banks, which differed widely.

The disadvantages of this system of many independent banks, with their reserves widely scattered or redeposited in city banks, became apparent, not only at every period of serious credit stringency, but also at times of normal seasonal demands for funds. There was no certain means by which a fairly inelastic supply of credit and currency could be supplemented at times of stress. Other difficulties arose from the lack of a competent fiscal agent for the Government. Under a plan instituted in 1846, known as the Independent Treasury system, all revenues were paid into the Treasury or a Subtreasury in actual cash, causing stringency, especially as taxes were largely collected at certain seasons of the year. Then the disbursements caused undue plethora of funds. To overcome this the Government deposited money in the national banks. Abuses grew out of that practice. In time of stringency the Government had to take special, and frequently extraordinary, measures. The Treasury thus found itself with many of the responsibilities of a central bank of issue, but without the ma chinery necessary for fulfilling the duties of such a bank.

The evils arising from the lack of a central bank of issue and re discount were long recognized in the United States. In 1908 the U.S. monetary commission was appointed by Congress under the chairmanship of Senator Nelson W. Aldrich of Rhode Island and produced an exhaustive report covering monetary conditions in the United States and the experiences of other countries with banks of issue and rediscount. A change of political parties occurred and the recommendations of the Aldrich commission were not adopted. The Federal Reserve Act as passed, represented a series of compromises between the recommendations of the commission and other proposals. The act in its present form was largely a product of the Committee on Banking and Currency of the House of Representatives under the chairmanship of Carter Glass of Virginia. The principal points at which the Federal Reserve Act is a harmonization of differences between divergent interests, are its compromises between national and local interests, between Government and private interests and between banking and busi ness interests.

A

Federal System.—Most European countries have a single central bank of issue and rediscount; in the United States a plan more suited to its geographical area and psychological peculiar ities was found in the establishment of 12 such banks, each serv ing a different section of the country. Co-ordination in policy and practice between these banks is effected through the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, a Government body consisting of seven members appointed by the President for four teen-year terms, one of whom is designated chairman for a four year term and is the chief executive officer of the Board. The Banking Acts of 1933 and 1935 while retaining the regional sys tem, increased considerably the powers of this Government Board, but removed from its membership the Secretary of the Treasury and the Comptroller of the Currency, who had previously served ex-officio.

Public and Private Interests.

The twelve Federal Reserve Banks are privately owned, but ownership does not carry with it control, due partly to the extensive powers of the Board of Gov ernors of the Federal Reserve System, and partly to the composi tion of the boards of directors which are directly responsible for the operations of the Reserve Banks. The stock of the Federal Reserve Banks is owned by the member banks, each of which is required by law to subscribe to this stock in an amount equal to 6 per cent. of its own paid-up capital and surplus. Thus far mem ber banks have been required to pay in only half of their sub scriptions. The stockholding banks elect six of the nine directors of each Reserve Bank, but of these six, only three, the class A directors, are bankers, and the other three, class B, must be "actively engaged in their district in commerce, agriculture, or some other industrial pursuit," and cannot be officers, directors, or employees of any bank. The three class C directors, one of whom is designated chairman of the board and Federal Reserve Agent, are appointed by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. They cannot be officers, directors, employees or stockholders of any bank. The principal executive officer of each Reserve Bank under the Banking Act of 1935 is the president, who with the first vice-president is chosen by the board of direc tors for a five-year term, subject to the approval of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.Dividends on the capital stock of the Reserve Banks are lim ited to 6 per cent. per annum, and any remaining earnings beyond expenses and dividends are paid into a surplus fund. In the event of dissolution or liquidation of a Reserve Bank, all assets after payment of all debts and repayment of the par value of the capital stock are payable to the Government. These provisions remove any pressure for profits and enable those in charge to make decisions with the primary aim of serving the public.

The Reserve Banks are not Government Banks, but in view of the extensive supervisory powers exercised by the Government and the public character of the business conducted by these banks it might be said that they are quasi-governmental or quasi-public. The composition not only of the boards of directors of the Re serve Banks but also of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System is designed to give diversified representation in the management of the System. The sentence in the Federal Reserve Act specifying the composition of the Board of Governors reads : "In selecting the members of the Board, not more than one of whom shall be selected from any one Federal Reserve district, the President shall have due regard to a fair representation of the financial, agricultural, industrial, and commercial interests, and geographical divisions of the country." A body known as the Federal Advisory Council was also created by the Reserve Act, composed of one representative from each Federal Reserve District elected annually by the boards of direc tors of the respective Reserve Banks, and required to hold at least four meetings each year. This Council is authorized to con fer with and make recommendations to the Board of Governors.

Growth of the System.

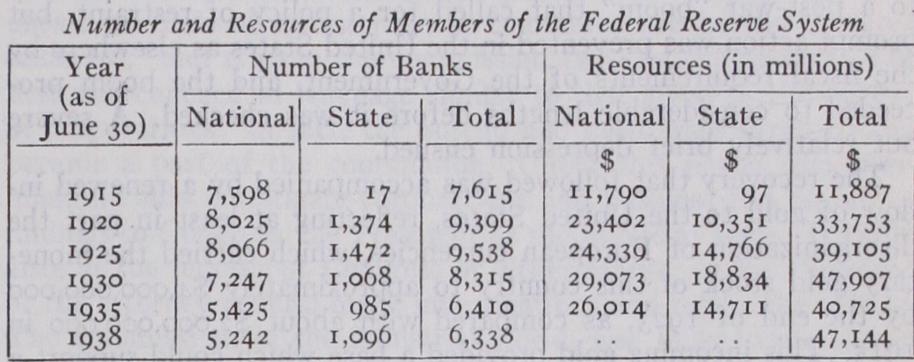

The original provisions of the Fed eral Reserve Act as to membership required all National banks in the respective districts to become members of the system, and permitted State banks to become members subject to certain conditions, including a minimum requirement as to capital and surplus and a financial condition and character of management satisfactory to the Federal Reserve Board (now Board of Gov ernors). Every member bank was required by law to deposit with its Reserve Bank a percentage of its net demand and time deposits. The most rapid growth in the membership of the System took place during and following the World War, as the accom panying table indicates. From 1925 to 1935 the number of mem ber banks was reduced nearly one-third. Mergers were the prin cipal factor in the reduction from 1925 to 1929, but between 193o and 1933 the unprecedented wave of bank failures, which reduced the total number of banks in the United States from about 25,000 to less than 15,000, eliminated a number of the weaker member banks, as well as a much greater number of non-member banks. From 1933 to 1935 membership in the System was increased somewhat, as a number of banks which previously had been non members joined the System in those years. About 4o per cent of the banks of the country with 85 per cent. of the banking re sources are now members of the System.

The growth in membership during the World War period is typical of all the operations of the Reserve Banks. With the entry of the United States into the World War in April 1917, there was suddenly thrown upon the Reserve Banks the responsi bility for handling Government financial operations and with it a great increase in lending operations, currency payments, check clearings, etc. The sale of huge war loans and short-time Treasury loans made it necessary for the member banks to begin borrowing heavily at the Reserve Banks and, simultaneously, war prices and war wages led to a large demand for additional currency which was met by the issue of Federal Reserve notes. The Reserve System thus was forced into an expansion which under normal conditions could have been the result only of many years of growth.

Following the conclusion of the war and post-war expansion, there were reductions in the amount of loans to member banks, the amount of Federal Reserve currency in circulation, and the size of fiscal agency operations. Other phases of the work con tinued, however, in increasing volume, as for example, the num ber of checks handled in the Federal Reserve collection system and the amount of currency received and paid out.

The total number of employees of the Reserve System is about 12,000. The largest Reserve Bank is that at New York, which em ploys some 2,400 people and being situated in the country's prin cipal money market carries on between one-quarter and one-third of the System's operations, including the handling of all foreign accounts and a large part of all direct operations in the money market.

By the terms of one of the clauses in an act of Congress signed by President Coolidge on February 25, 1927, the charters of the Federal Reserve Banks, which under the terms of the original act were for a period of 20 years, were made indeterminate and will continue indefinitely unless terminated by act of Congress.

Credit Policy.

Although the more mechanical functions, such as the supplying of money and the expediting of business settle ments between the different parts of the country constitute the bulk of the operations of the Reserve Banks, the major function of the Reserve System, in common with other principal central banks, is that of exerting an influence toward proper adjustment of the money and credit supply to the business of the country. The credit policy of the Reserve System has been in process of gradual development a little over twenty years in which monetary problems have involved extraordinary difficulties.At the outset it appeared from the experience in earlier crises that the chief need in the monetary organization of the United States was greater flexibility. But the establishment of the Re serve Banks was practically coincident with the outbreak of the World War in Europe which quite changed the monetary outlook and problems. For within a few months there was a heavy flow of gold to the United States, due to European war purchases. This gold flow, together with a reduction by the Federal Reserve Act of the legal reserve requirements of member banks, made the market and the member banks independent of the Reserve System and formed a base for credit expansion and price advances. The entry of the United States into the World War in 1917 made necessary a huge volume of Government financing through the use of bank credit, and the facilities of the new banks of issue were put vigorously to work. During this period the efforts of the Re serve System were perforce directed largely to facilitating the financing of Government requirements. After the war the infla tionary tendencies that developed out of the war expenditures led to a post-war "boom" that called for a policy of restraint, but prompt action was prevented in the United States as elsewhere by the fiscal requirements of the Government, and the boom pro ceeded to considerable lengths before it was checked. A severe but relatively brief depression ensued.

The recovery that followed was accompanied by a renewed in flow of gold to the United States, reflecting at least in part the disorganization of European currencies, which carried the mone tary gold stock of this country to approximately $4,000,000,000 by the end of 1923, as compared with about $2,000,0o0,o0o in 1915. This incoming gold provided a base which could support a very large expansion of bank credit. Under these conditions the Federal Reserve System found it difficult to follow what are sometimes considered orthodox precedents in its credit policy, as discount rate policy had to be guided largely by the nature and extent of credit expansion in the United States in its relation to business, rather than by any need for protecting the country's gold supply. The System was faced with a dilemma in that a dis count rate high enough to discourage excessive credit expansion in the United States would tend still further' to draw gold from European countries, and thus retard the stabilization of Euro pean currencies on the one hand, and provide a basis for further credit expansion in the United States on the other.

Despite this unusual credit situation, or perhaps partly because of it, the decade of the twenties was not only one of extraordinary prosperity in the United States but one of considerable stability of business and prices. The volume of production was high and advancing; the National income rose steadily; real wages ad vanced ; the country's standard of life rose.

Because there was no rise in commodity prices it was believed by many that the country had avoided the dangers which admit tedly lay in the huge gold holdings and the continued imports. But while commodity prices did not rise, inflationary forces were at work. The volume of bank credit advanced rapidly, and freely available credit was reflected in rising wages, an extraordinary amount of building construction, land booms in Florida and many urban centres, a large volume of new financing, and especially in rising prices of securities.

From time to time during this period business and nnancial movements appeared to be sensitive to Federal Reserve policy, which took the form of discount rate changes and open market operations, that is the purchase or sale of Government securi ties. But as the period of prosperity continued the sensitiveness decreased until in 1928 and 1929 even the most vigorous restrain ing action proved relatively ineffective.

Successive advances in discount rates and heavy sales of Gov ernment securities by the Reserve Banks in 1928 and 1929 were indeed successful in checking expansion of member bank credit, but the security market boom of those years was financed largely through loans from lenders other than member banks, including non-member banks, domestic corporations and individuals, and foreign lenders ; so that Federal Reserve efforts at restraint were circumvented.

In

the world-wide depression that followed, the Reserve System undertook promptly to ease the position of member banks and thus to remove, as far as possible, pressure on member banks for forced liquidation of credit. But the collapse not only of security values but also of commodity and property values between 1929 and 1932, together with serious financial disturbances abroad and large international movements of capital, led to public apprehen sion as to the condition of the commercial banks in this country and provoked heavy withdrawals of deposits in currency, which weakened the position of many banks and resulted in forced liquidation of bank credit on a large scale. So many commercial banks were unable to meet the extraordinarily heavy withdrawals that a general bank holiday was forced early in March 1933. In a few days' time an emergency banking act was passed, and all those banks which could be certified as sound were reopened. The shrinkage in bank credit caused by bank failures was a serious deflationary influence, but subsequently the volume of bank credit has gradually recovered with the aid of various extraordinary measures for assisting the banks.During this period the Reserve System maintained very low dis count rates—I2 per cent. in New York for many months—and through open market operations kept an ample supply of funds in the banks pressing for use. Furthermore, from 1934 to 1935 there was an extraordinary inflow of gold, which, following an increase in the monetary gold stock of the United States from $4,000,000, 000 to $6,800,000,000 due to revaluation of gold from $20.67 to an ounce, raised the gold stock to above $16,000,000,000 and more than doubled the reserves of member banks. Conse quently, member banks by July 1939 held nearly four and one half billion dollars of excess reserves.

Legislative Changes.

The events of the boom and the de pression led to a number of changes in the Federal Reserve Act. These took three principal forms : (1) measures to relieve credit stringency; (2) the greater centralization of credit powers in the National Government; and (3) the provision of additional meth ods for checking credit expansion especially for speculative use. Some of these provisions may be listed briefly under the three headings:—(I.) Measures to relieve credit stringency: (a.) Liberalizing of eligibility requirements for Reserve Bank loans to member banks. (b.) Insurance of bank deposits, which tends to lessen the danger of forced liquidation due to extraordinary with drawals of deposits. (c.) Emergency provisions for liberalizing collateral requirements for Federal Reserve notes. (d.) Authoriza tion to Reserve Banks to lend working capital to industries in cases where it is not obtainable from the usual sources. (2.) Greater centralization of power: (a.) Removing all gold from Federal Reserve Banks to the Treasury. (b.) Placing a two bil lion dollar stabilization fund in the hands of the Secretary of the Treasury. (c.) Placing control of open market operations in an open market committee composed of the seven members of the Board of Governors and five representatives of the Reserve Banks. (d.) Appointments of President and first Vice-President of each Reserve Bank made subject to approval by the Board of Gov ernors. (3.) Added methods of checking expansion: (a.) Board of Governors given power to raise reserve requirements of member banks. (b.) Board of Governors given various powers to check collateral loans of banks. (c.) Board of Governors given power to fix margin requirements for loans on securities. (d.) Lenders other than banks prohibited from making loans to brokers and dealers in securities through a member bank.These last-named additional powers for the control of credit expansion place the Reserve System in better position to deal with such developments as those of 1928-1929. It must also be recognized that the economic and financial situation which the banking system faces is in some respects similar to the situation of the twenties. Business has made a considerable recovery from a great depression. The currencies of the world are again dis organized, as they were in the early twenties, and there is an even stronger tendency for gold to flow from other countries to the United States, building up a huge supply of loanable funds. Only a small part of the funds available has as yet been put to work in an expansion of bank loans and investments, for the effects of the depression are still evident in a small demand for business credit. Potentially, however, the basis now exists for a very large credit expansion. Thus, looking into the future, the problems of Federal Reserve policy appear to have much in common with the problems of the twenties, with this difference that the Reserve System now has added powers of restraint.

See Carter Glass, An Adventure in Constructive Finance (192 7) ; The Federal Reserve System, Its Purposes and Functions, published by Board of Governors (i939). (G. L. H.; X.)