Franks

FRANKS. The earliest mention in history of the name Franks is an entry on the Tabula Peutingeriana, "Chamavi qui et Pranci." The earliest occurrence of the name in any author is in the Vita Aureliani of Vopiscus, referring to the year 245.

All the Germanic tribes, which were known from this time onwards by the generic name of Franks, doubtless spoke a similar dialect and were governed by customs which must scarcely have differed from one tribe to another—all they had in common. Each tribe was politically independent ; they formed no confedera tions. Sometimes two or three tribes joined forces to wage a war; but, the struggle over, the bond was broken, and each tribe re sumed its isolated life.

Of these tribes the Salians were to become most prominent. They are mentioned for the first time in 358, by Ammianus Mar cellinus (xvii. 8, 3) . At this time they occupied the region south of the Meuse, between that river and the Scheldt. The Caesar Julian defeated them completely, but allowed them to remain as foederati of the Romans. They perhaps paid tribute, and they certainly furnished Rome with soldiers ; Salii senores and Salii juniores are mentioned in the Notitia dignitatum, and Salii appear among the auxilia palatina.

At the beginning of the 5th century, when the Roman legions withdrew from the banks of the Rhine, the Salians, installed them selves in the district as an independent people. The place-names became entirely Germanic ; the Latin language disappeared; and the Christian religion suffered a check, for the Franks were to a man pagans. The Salians were subdivided into a certain number of tribes, each tribe placing at its head a king, distinguished by his long hair and chosen from the most noble family (Historic Francorum, ii. 9) .

The most ancient of these kings, reigning over the principal tribe, who is known to us is Chlodio. Towards 431 he crossed the great Roman road from Bavay to Cologne, which was protected by numerous forts and had long arrested the invasions of the barbarians. He then invaded the territory of Arras, but was se verely defeated at Hesdin-le-Vieux by Aetius, the commander of the Roman army in Gaul. Chlodio, however, soon took his re venge. He explored the region of Cambrai, seized that town and occupied all the country as far as the Somme. At this time Tour nai became the capital of the Franks.

After Chlodio a certain Meroveus was king of the Salian Franks. Perhaps the remarks of the Byzantine historian Priscus may refer to Meroveus. A king of the Franks having died, his two sons disputed the power. The elder journeyed into Pannonia to obtain support from Attila ; the younger betook himself to the imperial court at Rome. "I have seen him," writes Priscus; "he was still very young, and we all remarked his fair hair which fell upon his shoulders." Aetius welcomed him warmly and sent him back a friend and foederatus. In any case, Franks fought (451) in the Roman ranks at the great battle of the Catalaunian fields, which arrested the progress of Attila, and there is some evidence that Meroveus was among the combatants. Towards 457 Mero veus was succeeded by his son Childeric. At first Childeric was a faithful foederatus of the Romans, fighting for them against the Visigoths and the Saxons south of the Loire ; but he soon sought to make himself independent and to extend his conquests. He died in 481 and was succeeded by his son Clovis, who conquered the whole of Gaul with the exception of the kingdom of Burgundy and Provence. Clovis imposed his authority on the other Salian tribes, and put an end to the domination of the Ripuarian Franks.

These Ripuarians had settled in the 5th century on the left bank of the Rhine, but their progress was slow. It was not until the middle of the century that they occupied Cologne, which was not permanently in their possession until 463. The Ripuarians subsequently occupied all the country from Cologne to Trier.

Aix-la-Chapelle, Bonn and Zulpich were their principal centres, and they even advanced southward as far as Metz, which appears to have resisted their attacks. The Roman civilization and the Latin language disappeared from the countries which they oc cupied; indeed it seems that the actual boundaries of the German and French languages nearly coincide with those of their dominion. In their southward progress the Ripuarians encountered the Ala manni, who, already masters of Alsace, were endeavouring to extend their conquests in all directions. The Ripuarians long remained allies of Clovis, the son of their king fighting under him at Vouille in 507. Ultimately, however, Clovis destroyed the Ripuarian dynasty and was himself chosen as king of this people. Thus the Salian Franks united under their rule all the Franks on the left bank of the Rhine. During the reigns of Clovis' sons they again turned their eyes on Germany, and imposed their suzerainty upon the Franks on the right bank. This country, north of the Main and the first residence of the Franks, then re ceived the name of Francia Orientalis, and became the origin of one of the duchies into which Germany was divided in the loth century—the duchy of Franconia (Franken).

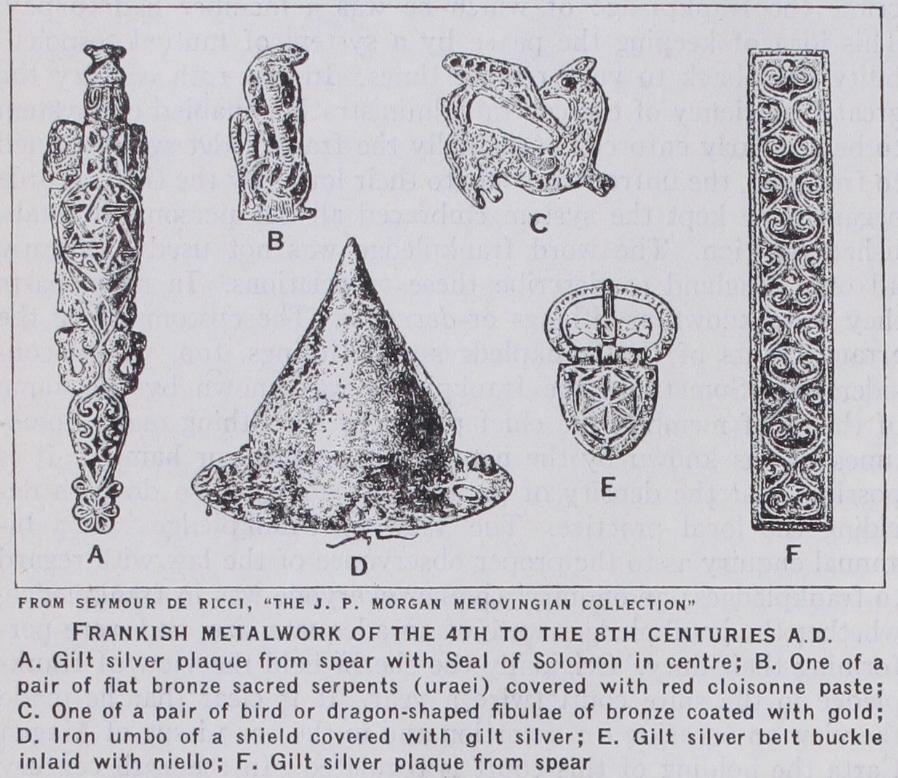

The Franks were redoubtable warriors, and were generally of great stature. Their fair or red hair was brought forward from the crown of the head towards the forehead, leaving the nape of the neck uncovered ; they shaved the face except the upper lip. They wore fairly close breeches reaching to the knee and a tunic fastened by brooches. Round the waist over the tunic was worn a leathern girdle having a broad iron buckle damascened with silver. From the girdle hung the single-edged missile axe or francisca, the scramasax or short knife, a poniard and such arti cles of toilet as scissors, a comb (of wood or bone), etc. The Franks also used a weapon called the framea (an iron lance set firmly in a wooden shaft), and bows and arrows. They protected themselves in battle with a large wooden or wicker shield, the centre of which was ornamented with an iron boss (umbo). Frank ish arms and armour have been found in the cemeteries which abound throughout northern France, the warriors being buried fully armed.

See E. von Wietersheim, Geschichte der Volkerwanderung, 2nd ed., edit. by F. Dahn (Leipzig, 188o-81) ; R. Schroder, "Die Ausbreitung der salischen Franken," in Forschungen zur deutschen Geschichte, vol. xix.; K. Lamprecht, Frankische Wanderungen and Ansiedelungen (Aix-la-Chapelle, 1882) ; K. Mhllenhoff, Deutsche Altertumskunde (1883-190o) ; Fustel de Coulanges, Histoire des institutions politiques de l'ancienne France—l'invasion germanique (1891) ; W. Schultz, Deutsche Geschichte von der Urzeit bis zu den Karolingern, vol. ii. (Stuttgart, 1896) Also the articles SALIC LAW and GERMANIC LAWS, EARLY. (C. Pr.)