Furniture Manufacture

FURNITURE MANUFACTURE. Furniture manufac turing is one of the oldest industries. Up to the latter part of the 19th century, the trade was essentially a craft industry. Little of it still survives in that form, even in high-grade work, owing to the introduction of machinery, which is always used for doing the heavier operations of planing and sawing, from the log to the board. The extensive use of machinery has enabled furniture to be made at a price to place it within the reach of all classes.

The industry is divided into various sections; in many cases individual firms specialize in one particular class of goods. On the other hand, there are some firms which embrace a variety of these divisions. The principal classifications are bedroom suites, sideboards, chairs, fancy goods and cabinets, office furniture, wood bedsteads, hall and kitchen furniture, school furniture and up holstery. The last division is dealt with under a separate article under that title. (A description of the industry in the United States is given in a section at the end of this article.) Geographical Distribution.—In the United Kingdom the principal centres of the industry are London, High Wycombe, Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, north-east Lancashire, parts of Yorkshire, north-east coast, Nottingham, Bath, Bristol and Barnstaple, and Scotland. The town of High Wycombe is prin cipally engaged in the manufacture of chairs, an industry dating from the time when the windsor chair was first manufactured there, owing to the plentiful supply of beech trees in Buckingham shire. The Bath area is noted for high-grade furniture. The largest individual British firms are situated at Tottenham, London, and Colwick, Nottingham.

Machine and Hand Work.

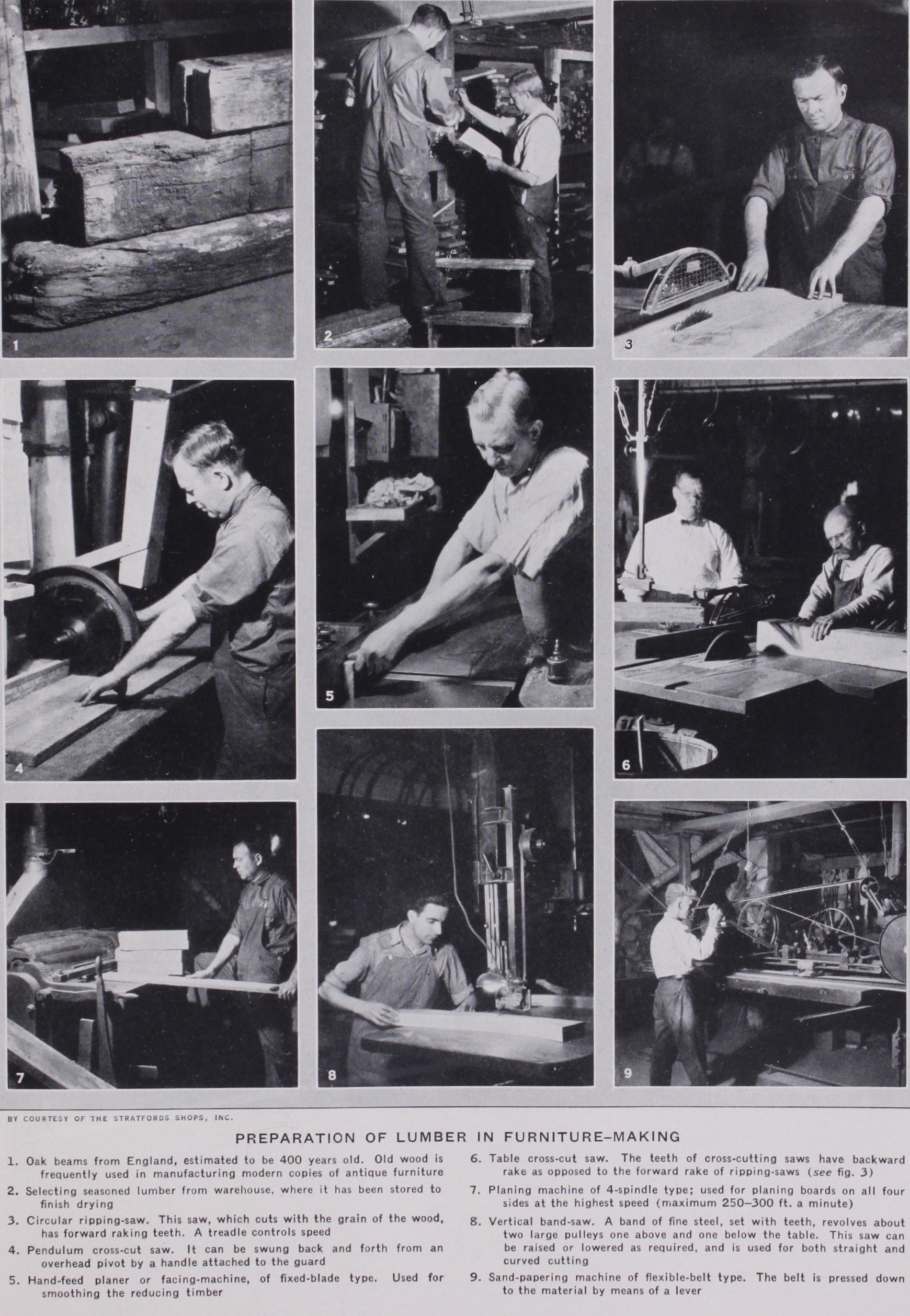

The industry is subdivided into what are known as machine shops and hand shops. In the first named, the bulk of the machine work is done on the same prem ises, and is extensive in its character. In the case of the "hand shop," it must not be thought that the furniture is produced entirely by hand. On the contrary, a considerable amount is still done by machines, but not done on the premises, the work being sent out to what is termed a trade mill, where a complete range of machines is available, and various operations are per formed on the timber for the purpose of lessening the cabinet maker's task. This arrangement is very convenient for small manufacturers who are not in the position to afford the capital cost of laying down an extensive plant. Many of these workers are almost home workers, performing their operations in a part of the house, or in a large shed at the back of it. Cheap fur niture made in this class of workshop is sometimes termed garret made furniture. This process, although wasteful from the point of view of labour in carrying the material backwards and forwards to the trade machine mill, avoids the stand-by losses caused when workshops are too small to keep a machine shop fully occupied.The principal machinery employed in machine shops consists of swing or pendulum saws, circular rip saws, overhand planers, planing and thicknessing machines, cross-cut circular saws, band saws, fret saws, spindle moulding machines, fourcutter moulding machines, tenoning machines, lathes, dovetailing machines, boring machines and sand-papering machines of various types, such as triple drum, belt, disk, up-and-down, etc.

Cabinet-making.

The chief methods of jointing used by the cabinet-maker are mortising and tenoning and scribing, dove tailing, dowelling, tonguing and grooving and mitring. Owing to the modern extensive use of machinery the operations of a cabinet-maker are largely reduced to the fitting and running of drawers, the hanging of doors on hinges or centres, and the general assembly of the main carcass of goods. This latter operation, however, is in some works executed in a machine shop, cramping in particular being done by large mechanical cramps, designed to operate in three directions successively—transversely, vertically and longitudinally.The chair industry is mainly concentrated at High Wycombe. The trade there has developed from the windsor and cheap bed room chair to high grade reproductions of old styles such as Chippendale, Sheraton, Hepplewhite, etc.

Polishing.

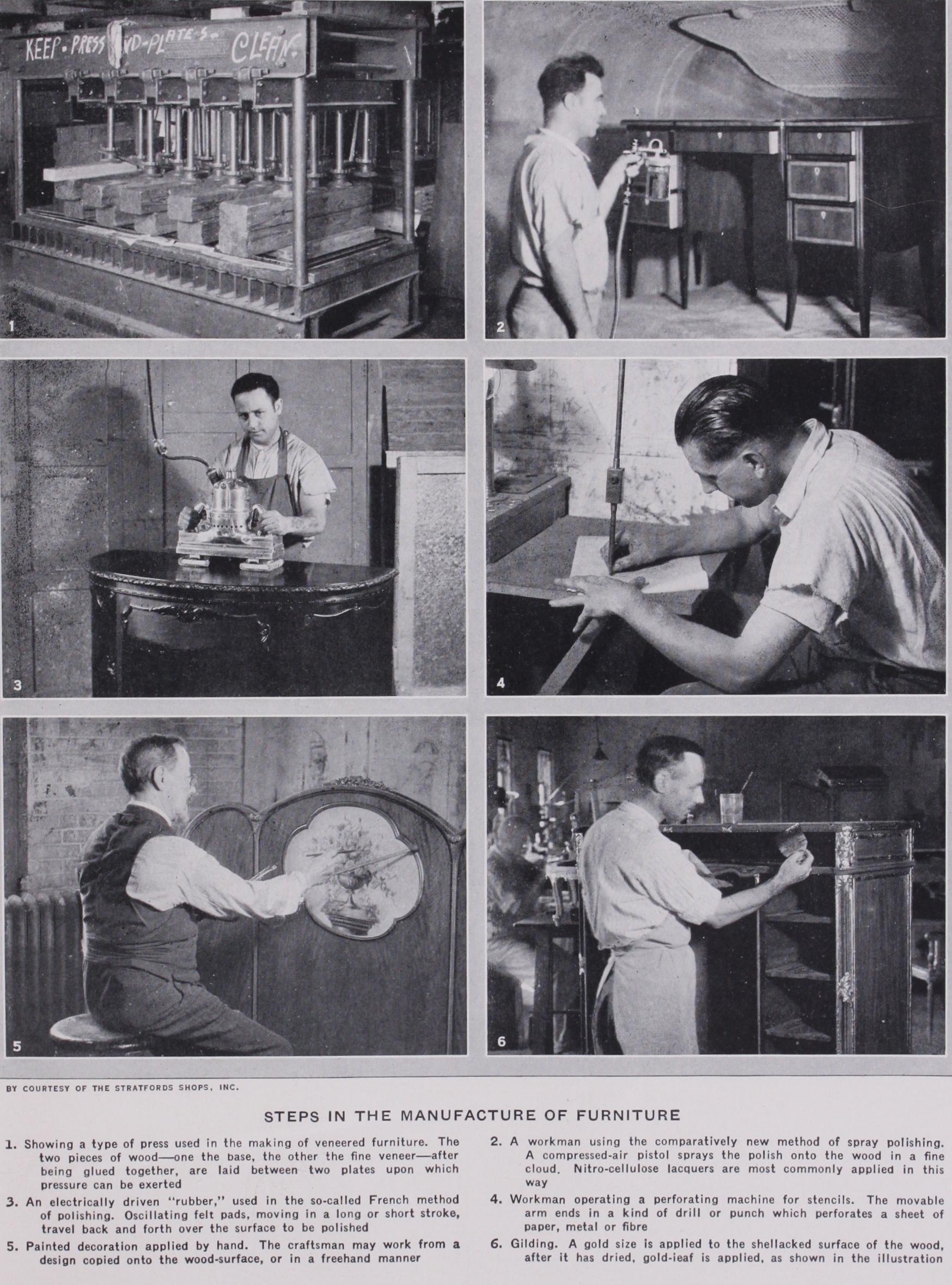

Polishing is divided into French polishing, wax polishing and spray polishing. Most woods are usually stained before polishing. Stains may be made of water, spirit or oil.The process of french polishing varies slightly, according to the nature of the wood. If it is intended to have what is known as a full polished effect, it is necessary to fill the grain of the wood, full polished being the term used to denote an even smooth surface over all the wood, no open grain showing in its natural state. Various fillers are employed, usually either plaster or what is known as American patent filler. The filler is well rubbed into the grain of the wood, and then allowed to stand a considerable time to harden. If plaster is used, it is usual to oil the whole of the work with linseed oil, to "kill the plaster," i.e., to prevent it looking white and murky, and to give a transparent effect to the subsequent coating of polish.

The next process is known as bodying up, and consists in applying a coat of shellac polish (consisting of shellac dissolved in methylated spirits) by means of what is known as a rubber, which consists of a pad of cotton-wool saturated to a suitable extent with shellac polish and covered with a piece of linen rag which acts as a filter and allows the polish to be distributed evenly. After a certain amount of work, it is necessary to apply a small amount of linseed oil to the rubber to prevent it from "hanging," that is from dragging the polish off. After this process has been continued for a certain length of time, the work is allowed to stand so that the polish can sink into the wood and harden. The surface is then cut down, as it is termed, either by fine sand-paper or pumice powder. After that, it is again bodied up. Every process is continued in succession according to the degree of finish re quired. The greater the length of time allowed to elapse between the operations, the safer is the result obtained in permanence and beauty of finish. A fortnight or three weeks is by no means an excessive time for these operations to take in high-class work. The greatest objection to this process is the difficulty in the use of oil, any excessive amount being subsequently exuded by the polish as sweating. As it is a matter of individual judgment, greatly dependent also on atmospherical conditions and tempera ture, it is very difficult to get uniformity of working, and con sequently the french polishing process cannot be termed ab solutely reliable.

Wax polishing is a much simpler process and consists in apply ing to the wood beeswax and turpentine which has been melted to a suitable consistency and subsequently allowed to get cold. A stiff brush is used to ensure that the wax does not remain in the grain of the timber. This is nearly always used for open grain effects. The wood is not filled in this method.

Spray polishing has been introduced for the purpose of using cellulose lacquers, either nitro-cellulose or cellulose-acetate dis solved in suitable solvents such as acetone, amyl acetate, butyl acetate, with the addition of certain other substances termed plasticesers to prevent excessive brittleness, such as tri-phenol phosphate. Usually in addition there is a certain amount of petrol or benzol in the mixture to facilitate rapid drying. It is on account of the rapid drying of these lacquers that it is neces sary to spray them on to the wood. To effect this a pistol or gun is used, which works like a scent-spray. Compressed air at about 45 to 70 lb. pressure is used to spray liquid from a jet, the air acting as an atomizer and causing the liquid to be broken up into a fine cloud. When this process is used it is necessary to avoid all use of oil, as that is detrimental to the cellulose compounds. The fact that no oil is used avoids the defects above mentioned in regard to french polishing.

Works Organization.—In large works the principal depart ments are as follows, and the order of working is in the sequence mentioned: The drawing office produces original ideas or works on the traditional designs and examples of the old cabinet-masters. This section also makes full-size working details, which are then passed over to the works proper, where the job is technically known as "set out," every piece of wood employed in the job being marked out on a board or rod. From this, a cutting or works order is made (in U.S.A. termed a stock bill), giving the exact dimensions of each finished piece. In some works a duplicate order giving outside dimensions to allow for trimming and shrinking, is also supplied. This order is issued to the timber yard so that the requisite timber can be taken from store and delivered to the machine shop to be cut up in accordance with the instructions.

If the timber has not been purchased as dry timber it is necessary to ensure its being seasoned, either by natural or artificial methods. This consists in what is known as sticking, that is, piling the timber board by board or plank by plank, one above the other with a narrow strip of timber placed in between every board cross-wise, at approximately every i8in. along the length of the plank or board. It is most essential that these sticks be kept vertically over one another as the pile is increased in height, otherwise there is a tendency for the timber to warp or become wavy owing to the pressure on each board not being sustained by the one immediately underneath. Much good timber is often spoiled through careless sticking. If the natural method of seasoning is employed, the timber is piled first of all in the open and then subsequently put under cover, or alternatively is put under cover straight away, but so situated that there is a good current of air through the building. If, however, the wood is to be seasoned by an artificial process, it is still sticked, but placed in a drying kiln, usually on specially constructed trolleys which allow it to be easily pushed along from one kiln to another in successive stages. The process consists in some suitable method of introducing hot moist air, humidity at the start being at its greatest and gradually being reduced in subsequent stages. By this means the outside of the timber is not hardened, but the excess internal moisture of the wood is driven out by the heat, the humidity of the air not being fully at saturation point. As this process is continued, the moisture content of the air is gradually reduced until the whole timber becomes what is known as bone dry. The moisture content of the wood should then be from 6% to 12%. • When the timber passes to the machine shop it is first dealt with by the swing or pendulum saw and cross-cut into lengths for all those parts which are required to have all their edges worked upon. On the other hand, where long lengths are re quired, mouldings sometimes are worked in those long lengths to be cut up subsequently, this being a matter of convenience for ease of feeding the machines. All timber which is used for large flat surfaces is then passed over the overhand planers for the purpose of planing "out of wind," as it is termed, that is, ensur ing that the whole surface of the timber is uniform, and able to rest on a flat surface without rocking. After that, according to the particular nature of the piece and its ultimate destination in the assembly of the goods to be made, it passes to the various individual machines above mentioned, either for bringing to a definite thickness, or moulding, boring, tenoning, sandpapering, etc.

When the wood has been fully machined, there are two distinct methods employed according to the type of works. One is to store these various parts in a special place where they can be drawn upon as required, the other is immediately to assemble the whole of the quantity machined. In some shops, a good deal of the work formerly executed by the cabinet-makers is done in either a cabinet or second machine shop, or is passed back after the cabinet-maker has done certain operations. For instance, cramping up various frames such as door frames, glass frames, etc., may be done in the machine shop, or may be done entirely in the cabinet-maker's shop by means of hand cramps instead of cramping machines. Then again, drawers may be fitted by hand by the cabinet-maker, or they may be sent back of ter assembly to be fitted in a drawer-fitting machine.

Some firms have so specialized the various processes that there is very little cabinet-maker's work to be done, and the cabinet maker becomes really an assembler, who only requires a glue pot, a hammer and a screw driver.

In the United States a beginning is being made in line as sembly on a belt conveyor similar to that used by motor-car manufacturers. Nothing like that has been attempted in England, the nearest approach being a system of roller conveyors in the machine shop for ease of movement in shifting the timber.

Scientific Research.—Work in this direction has been per formed by two separate bodies working in co-operation. The Forest Products Research Laboratory has been investigating the ravages of worm in timber work which has proved of great value to the trade. Also the Advisory Committee on Timbers of the Imperial Institute, South Kensington, London, has been conduct ing an exhaustive survey of British empire timbers, many of which, being suitable for furniture construction, have been in troduced to the market and should gradually come into extensive use.

Trade Unions.—The principal trade unions, on the operatives' side, are the National Amalgamated Furnishing Trades Associa tion, the Amalgamated Society of Wood-cutting Machinists, the Amalgamated Union of Upholsterers and the Progressive Society of French Polishers.

The first named has endeavoured to embrace all sections of the industry, but is chiefly concerned with cabinet-makers and polish ers. The others confine themselves to their particular sections. On the employers' side, the principal organizations are the National Federation of Furniture Trades, the London Cabinet and Upholstery Trades Federation, Yorkshire Employers Fed eration and Master Carvers Association, London. All these bodies except the last embrace both manufacturers and retailers in the industry, although they are divided into separate groups.

The operatives employed in the British industry, and the em ployers also, may be grouped into two divisions, the one British and the other Jewish. The trade is very largely in the hands of the Jews in many areas, particularly so in London. It is unusual to find Jewish workers in British shops, and vice versa.

Raw Materials: Timber.—The chief timbers used are oak, principally American, but also some Russian, Austrian and Japa nese; the mahogany used is chiefly Honduras, African and Cuba. Other woods are American walnut, satin walnut or red gum, hazel pine or sap red gum, whitewood, satinwood, beech, Canadian birch and deal and pine and various veneers, some of which are super imposed upon the woods above named.

Apart from timber, which naturally must be the principal raw material, and which is dealt with under a separate article on FURNITURE WOODS, the principal raw material employed in the industry is plywood, which is a manufactured product consisting of three or more separate veneers cemented together with the grain of each layer running at right angles to the previous layer, and which may be veneered with a final layer of some more ex pensive wood, the core being of cheaper grade timber which readily lends itself to cutting on a rotary veneer lathe. Plywood is principally manufactured in Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Germany and Belgium.

The other principal raw material is glass, of which the bulk is produced in Belgium. Brass-foundry work and locks are chiefly obtained from Birmingham and district. Materials for polishing consist of gums and lacs, the lac coming from India and gums from various tropical countries. Where cellulose is employed for the finishing process, it is largely manufactured in England.

It will be seen that little of the raw material of which furniture is made is British, the bulk being procured from abroad.

Furniture Styles.

Styles of furniture in England can be grouped into two categories, period styles and modern. The principal period styles are Tudor, Elizabethan, Charles, Jacobean, William and Mary, Queen Anne, Chippendale, Adams, Sheraton, Hepplewhite, Empire and Georgian. In addition to these essen tially British styles, there are the well-known Continental styles, Louis XIV., XV. and XVI. Of the older Continental styles which influence modern tendencies, may be mentioned Dutch Marquetry and Italian Renaissance.Among modern styles, as from the end of the Victorian era, may be mentioned the quaint art style, and the subsequent ver sions of the old period styles. Modern Jacobean is in no way a true example of old Jacobean furniture, it rather expresses the feeling, or is influenced by the tradition, of that period. The same is true of modern examples of so called Sheraton, Chippendale, Adams, etc. But many reproductions are manufactured as exact copies of fine old examples.

British Furniture Output.

The output of the British fur niture trade has been investigated by the official census of pro duction. The following figures are returned for the years 1907 and 1924:— In considering these figures it should be remembered that there was a great rise in prices between 1907 and 1924, and that it is very difficult, therefore, to compare them with accuracy. It is also recorded with regard to the repairs of furniture that there was a selling value of f220,000 in 1907 and of £1,315,000 in 1924.In the year 1924 the British exports of furniture were valued at £1,317,000, and the net imports at £563,000. In 1927 the British exports of furniture were valued at £1,232,000, while the net imports were valued at £815,000.

It is also shown that the number of persons employed in British furniture-making in 1924 was 82,841, of whom 71,238 were recorded as operatives and II,6o3 as belonging to the man aging, clerical and technical staffs. These figures, however, cover, in addition to furniture and cabinet-making, the persons employed in the upholstering, bedding and mattress trades.

The classification of the furniture manufacture in the United States is as follows: upholstered furniture; case goods (dining room and bedroom) ; kitchen (refrigerators, breakfast sets, etc.) ; novelty furniture; reed and fibre porch furniture; wrought cast iron.

Materials.

Metal, reed and glass are used in the manufacture of furniture but wood is in far more general use. The woods chiefly used are white ash, beech, birch, cherry, chestnut, elm, gum, mahogany, maple, oak, sycamore and walnut (see FURNITURE WOODS). Of recent years such scarce woods as ebony, amaranth, prima vera, tulipwood, teak, snakewood, rosewood and Ceylon satinwood have come into greater use because of their decorative possibilities.

Manufacture and Machinery.

Air-dried lumber is brought in by carloads into the factory yards, where it is so arranged that it may easily be conveyed by small electric trucks to the drying kilns. The lumber is carried from the kilns by electric lifts direct to the cutting room. The designing room after detailing the item to be manufactured enters a cutting order for the different lengths of lumber, and trucks convey the lumber to the cut-off saws. Elec tric motors blow the refuse of the furniture plant to a central point outside the factory and automatically the shavings, sawdust and cuttings are separated and conveyed or blown to the boilers as fuel. Waste material which is too heavy for the exhaust or blower is carried away by other methods to large revolving cylinders containing powerful knives which cut the refuse into small pieces and then deposit it in a bin.After leaving the cut-off saw the material then proceeds to the straight line ripper, which has an automatic feed. This machine removes the edges and rips the boards to a specified width; gluing then follows for the core work. The feed jointer operated by three motors is the next machine in line. For work requiring gluing, the automatic revolving clamp carrier then follows. The pieces to be glued are placed edgewise on plates, which are kept hot by steam coils. From the hot plates the work is taken to a revolving single roll glue spreader and then arranged in a clamp carrier. This clamp carrier holds the pieces together from 2 to 14 hours.

The rail lengths are sent direct to the surfacing machine, where they are planed to the desired width and thickness. The mitre saw then cuts the lengths to required size and a boring machine is used to place holes for dowel pins. A shaping machine is used if a special shape for rails and legs is desired.

Modern Machines.

The latest method eliminates consider able handling in having the truck loads stopped at the "straito plane." Here lumber is fed in at one end of the machine and comes out at the other end in boards of standard thickness and size. Next is the planer, which removes a thin coating, leaving the board ready for the veneer or sanding room. In the veneer room, the veneer clipper is used for cutting the various widths and lengths. For matching veneer the taping machine is required which binds and glues. In the final machine room are the moulders which have automatic feeders that are used for making large quantities of the same type of legs. Here also are the hand planers, mitre saws, high speed band sawers, double end cut-off saws, jig-saws, shapers and routers as well as dovetailers. Various high-speed boring machines are then in line on this machine floor.A machine in common usage is the multiple speed carver, operated by electric motors. Four to thirty-six carvings are duplicated at one time under the direction of a single operator. The sanding in preparation for finishing is also done by machines. Legs and framing used in furniture are often bent into desired shape. This is done under steam and pressure. Forms and shapes so bent are stronger than when machined, as it entirely eliminates end or cross-grain wood (see WOODWORKING MACHINERY).

Plywood and Veneer.

Usually the finer grains of woods are used for the outer surface to provide decorative effects. Irregular forms can be made of plywood more readily when glued and pressed into desired shapes. Veneers permit the use of the beauti ful grain woods cut from selected logs which are too costly to be used as solid wood. If the board is to be veneered, cross-grained veneer sheets are glued on to the surface of the board and thence taken to a power press, where they are held under hydraulic or motor pressure until perfect adhesion is secured. Then they are placed on the panel dry kiln, and then they undergo the sanding and finishing processes. Ash, basswood, beech, birch, cedar, cherry, cottonwood, cypress, Douglas fir, elm, gum, maple, ma hogany, oak, pine, poplar, spruce, redwood, sycamore and walnut, as well as all the rare woods, are used as veneers (see PLYWOOD). Finishing.—The piece is first sanded with fine sand-paper and stained. Stains may be evenly applied with a brush, rags or with a sponge, but a spraying device, according to many manu facturers, is the best method. Dipping in a large vat is sometimes resorted to. Stains comprise the several classes of water stains, acid stains, spirit stains and oil stains. To fill up the pores of the wood a thin coat or filler is next applied.

After this operation the final finish is given. The wax finish is obtained by applying two coats of shellac to the stained piece; sanding; and following with a coat of paste wax, which is rubbed about the surface with sand-paper until it is polished. Shellac finish is procured by applying two or three coats of shellac and sanding. When dry, a very fine pumice soap is sprinkled over the surface, upon which is poured rubbing oil that is rubbed with the grain. Varnish finish is made by coating the object with shellac; then sanding, and applying the desired number of coats of varnish.

Satin finishes are completed by polishing the varnished surfaces with rotten stone and water. Lacquer finish is gradually displacing varnish. The application is the same as varnish. Each successive lacquer coat forms part or the previous coat, whereas the varnish finish is an application of separate coats, one upon the other. Crackled finish is the result of applying a fast drying coat over a slower drying one. Polychrome finish is used only on surfaces having carvings, turnings or flutings. After the shellac coat is applied, which generally dries quickly, the basic coat follows, which may be coloured bronze, gold, oil colours or enamel. Upon drying, the dominant colour or smutting solution is applied, then wiped off with a cloth in spots to give the "high lighting" effect.

Production.

The U.S. Department of Commerce census of manufacturers' figures for furniture production are shown in the accompanying table.The principal furniture manufacturing centres in the United States are Chicago, Ill., New York, N.Y., Grand Rapids, Mich., Rockford, Ill., Jamestown, N.Y., High Point, N.C. Considerable furniture is also manufactured in the States of Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Indiana, California and Oregon. (See WOODWORK ING MACHINERY.) (L. KA.)