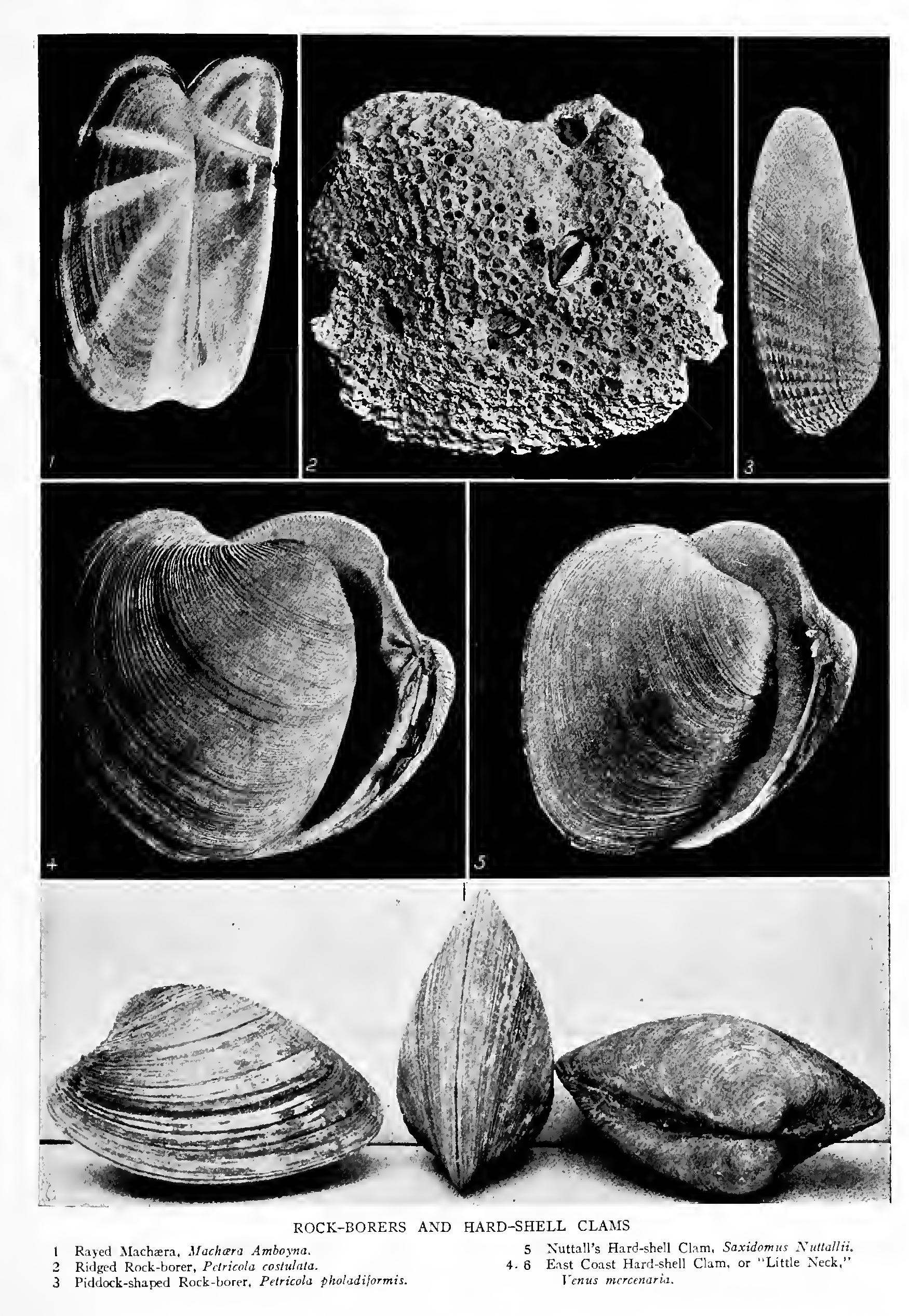

The Rock-Borers Family Saxicavidie

THE ROCK-BORERS FAMILY SAXICAVIDIE. Genus SAXICAVA, F. de B.

Shell

equivalve, thick, gaping at both ends; hinge with single cardinal tooth; ligament external, strong; animal symmetrical, elongated; foot finger-like; mantle, cavity closed, all but pedal 'opening; siphons large, long, covered with thick skin; orifices fringed. A small number of living forms; many fossil. Borers in sand, mud and soft rock.

The ways of this rock-borer are worth studying, for the mol lusk is in the same class with the Teredo, as an undoer of man's work. The boring it does in cement work, in breakwaters and embankments, causes serious damage. The cells are large, often six inches deep, and later corners bore through into cells already completed, greatly weakening the structure. Each individual attaches itself to the wall of its cell by a byssal cord, and thrusting its siphons forth, settles down for life. The same cells are occu pied by successive generations; the young attach themselves between the empty valves of parent shells. Thus several are found nested together in one cell.

The Arctic Rock-borer (S. Arctica, Linn.) is a representa tive of this family. It is found on cold New England coasts, boring soft limestone, and living in the cavities. It often burrows in mud or sand and affixes itself by a byssal cord to the root anchors of large seaweeds. It occurs also on the Pacific coast and in Northern Europe. It is largest in the coldest seas. Its shell is oblong, angular, wrinkled and harsh, with toothed lamina tions, fit instruments for rock-boring. The form on our east coast is less angular than the European, and larger. Length, to ri inches. Small forms occur on the Pacific coast.

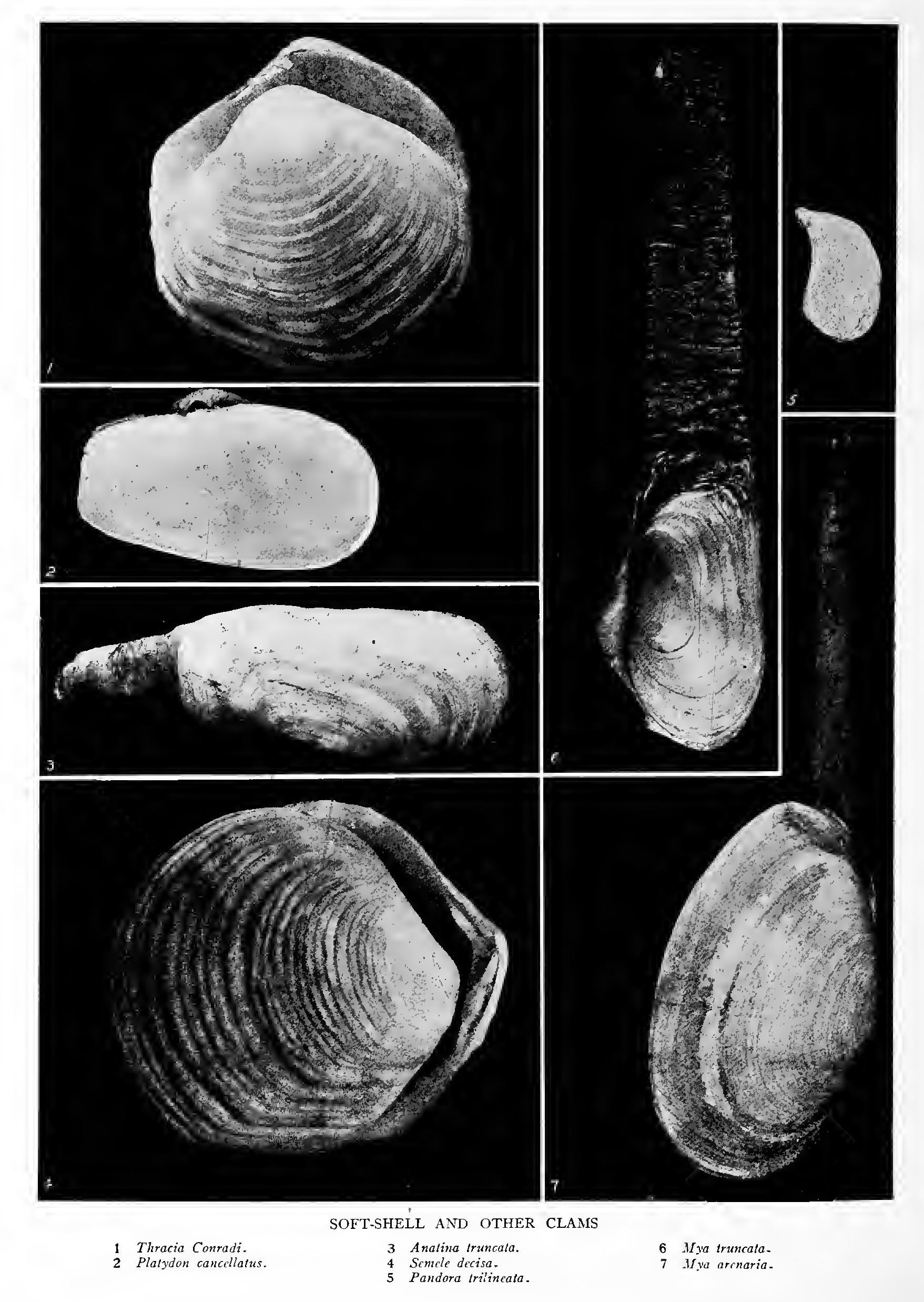

Genus PANOPJEA, Menard (GLYCIMERIS, Lam.) Shell oblong, thick, equivalve, gaping widely at both ends, usually smooth, with epidermis; hinge near centre of dorsal 322 The Rock- borers margins a horn-like tooth and a socket on each valve; ligament external, conspicuous; siphons separate at tips.

Few species, including some clams of unusual size, widely distributed, chiefly in cold seas.

r The Norwegian Panopma (P. Norwegica, Spengl., Glyci

meris arcticus, Lam.) is found off New England coasts and dis tributed by way of Arctic seas to Norway and Asia. Its trape zoid shell is thick, and each valve is divided into equal triangular thirds by two raised ribs that diverge from the hinge. The squared posterior end is broad, but scarcely more so than the great siphon tube that emerges, wearing its tough, dark skin in wrinkles until it is stretched at full length. In New England a good average of these shells is three inches long. In Norway they grow somewhat larger.

The Giant Panopma (P. generosa, Gld.) lacks the posterior diverging ridge on the shell. It is the largest bivalve of the west coast. Six inches, the average length, is often greatly exceeded. The valves are flat, almost right-angled behind, rounded in front; distinct concentric growth lines mark the dull white exterior; the lining is pearly. The foot is small. The siphons are large and united, their chief protection a thick, wrinkled skin. The tube reaches a full yard in length with a thickness somewhat exceeding that of a stout broom handle. When disturbed the mollusk throws out a powerful jet of water, and retires to a depth dis couraging to the collector.

"A truly noble bivalve!" is the characterisation applied by a conchologist who dug one out of the mud with the aid of two friends, one of whom had the arduous task of hanging on with a death grip to the great siphon, while he adjured his colleagues to dig for their lives, as his grip was likely to give out. This speci men weighed sixteen pounds. Dr. Stearns says: "The meat, when parboiled and fried in batter, is as tender as a humming bird's eye." The Indian name for this favourite clam is "Geoduck." It is found in Puget Sound.

Aldrovand's Panopma

(P. Aldrovandi, Lam.) of the Medi terranean is the giant of the genus. It is broad and deep, short and obliquely truncated in front. The lines of growth are uni form and distinct. Length, to inches.

The Attenuated Panopma (P. attenuata, Sby.) from Port Natal, South Africa, long and narrow, is another giant.

323