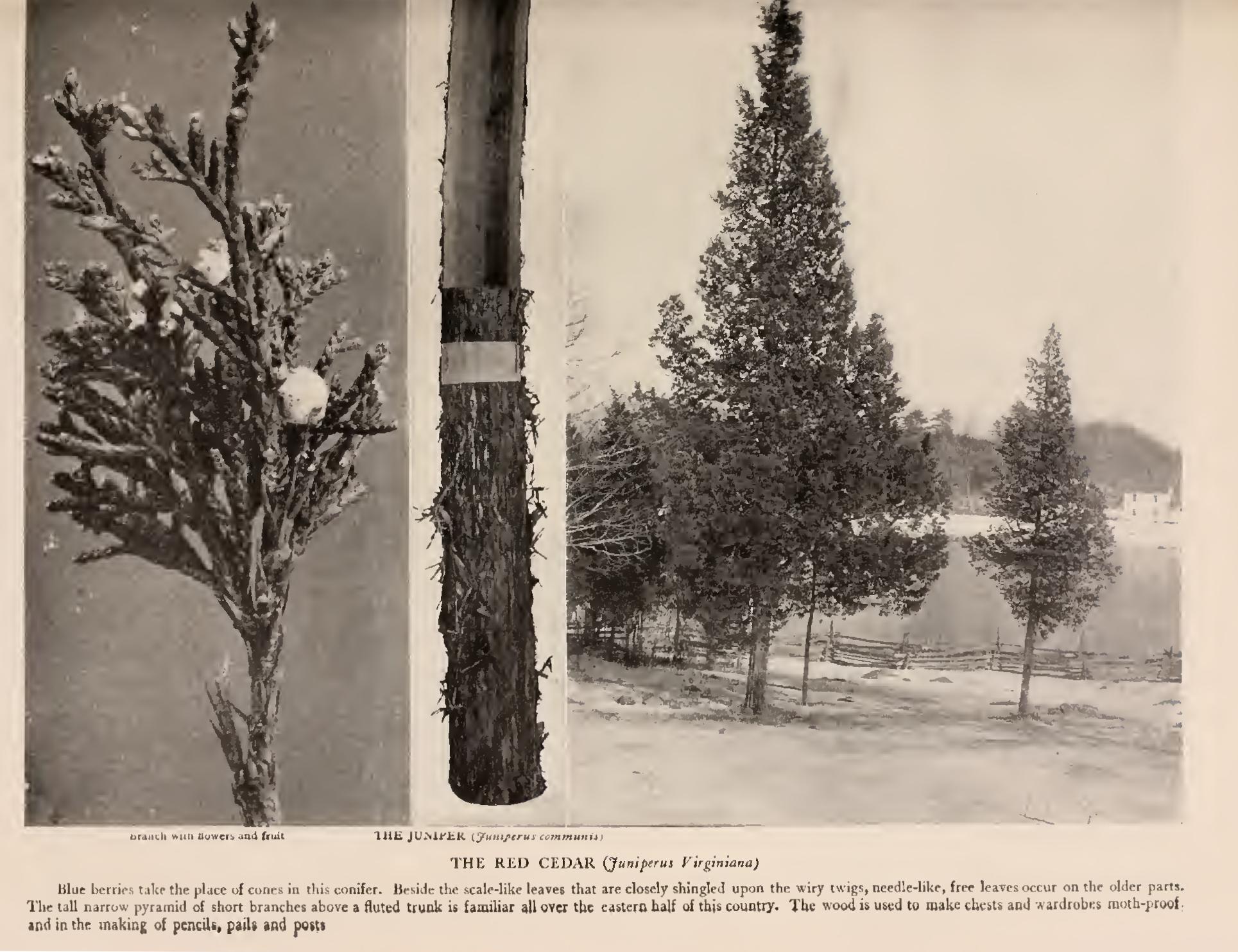

The Junipers

An interesting "fruit" of the red juniper, much larger and more luscious looking than the diminutive berries, is familiar to boys and girls under the name "cedar apple." A remarkable thing about these pulpy, jelly-like masses, with their yellow spurs, is that they come out on the twigs as suddenly as mushrooms. Still more astonishing is the fact that this parasitic fungus that makes itself at home on the red cedar utterly ignores all red cedars when its spores are germinating to produce the next generation. Only those that fall on apple trees live. They do not produce "apples" of any sort, but patches of yellow "apple rust" on leaves and fruit. Spores wafted away from these blotches germinate only when they fall on twigs of red cedar. They grow inside, and at fruiting time throw out the gelatinous cedar-apple mass whose spurs contain the spores.

This capricious "alternation of generations" is interestingly seen in wheat rust, whose alternate host is the common barberry. A third rust goes from birches to poplars and back again to birches each alternate year.

The Red Juniper of the South (Juniperus Barbadensis, Linn.) has long been considered by good authorities a variety of the preceding species. It furnishes the highest grade of "red cedar" for pencils. Western Florida has many swampy forests of these trees. The Fabers, of pencil fame, own vast tracts here. The West Indies and the Gulf States all contribute a considerable quantity to commerce each year. Growing naturally in swamps like the bald cypress, yet it thrives when planted in parks and cemeteries. 1t is the most beautiful of the junipers in cultivation. Its slender, spreading branches clothed with pendulous twigs, give unusual grace to the tree habit. The berries are silvery white and abundant. Its susceptibility to frost confines this tree's range to the Southern States.

The Rocky Mountain Juniper (funiperus scopulorum, Sarg.) has stout twigs and limbs, usually a short trunk with several main limbs carrying the top. Its foliage is often pale grey-green —a fashionable colour on the Western plains and foothills. It climbs to elevations of over 5,000 feet, and few soils are too poor and too arid to support it. It follows the Rocky Mountains from Alberta to Texas on the eastern slopes; on the western slopes it enters Washington, Oregon and California.

The larger fruit, requiring two years to ripen, the broader head, the stouter branches and twigs, the paler foliage, and the shreddy bark distinguish this species from the true red juniper which meets it on the hither boundaries of the Rockies, and from which it was but recently, separated by botanists.

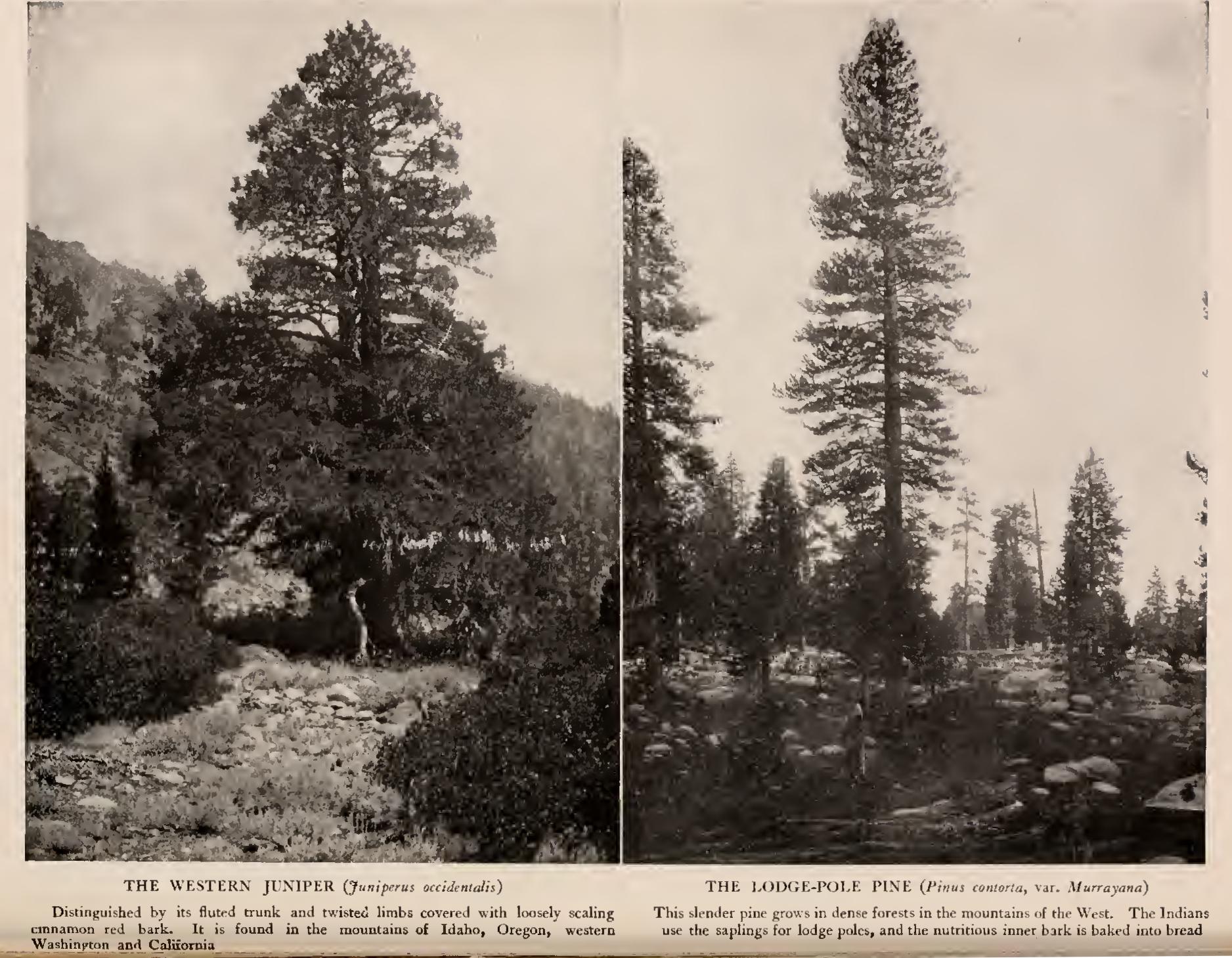

Western Juniper (Juniperus occidentalis, Hook.)—Low, broad-headed tree, 20 to 65 feet high, with unusually thick trunk and stout, horizontal branches. Bark inch thick, bright crimson red, in broad, scaly ridges, with shallow irregular interlacing fur rows. Wood soft, light, pale reddish brown, fine grained, very durable in the soil. Leaves in threes, minute, closely appressed to twigs, grey-green, tapering, sharp pointed. Flowers cone-like, moncecious, inconspicuous. Fruit a blue-black berry with pale bloom, to f inch long; seeds 2 to 3. Preferred habitat, mountain sides and elevated plains, 6,000 to to,000 feet. Distribution,

western Idaho, Washington, Oregon and California, following the Sierra Nevada Mountains to the San Bernardino range. Uses: Wood for fencing and fuel. Bark woven into mats and cloth by Indians. Fruit an important article of food among California tribes.

Here is one of the patriarchal trees of America—one whose age ranks it with the Sequoias, dating the birth of the oldest back, assuredly, more than 2,000 years. It is impossible to find a giant with trunk sound to the core and telling the whole story in its annual rings. John Muir is probably the only man who has made serious inquiry into this matter. On the bleak ridges of the Sierras, with no soil but crumbs of disintegrating granite, these trees make scarcely any gain from year to year. Two of Muir's measurements are given below, the years being determined by the number of annual rings.

Diameter of Trunk Age 2 feet ti inches 1,140 years foot 7f inches. 834 years Being a poet as well as a scientist, John Muir was deterred from the killing of one of the elders, merely to appease his curiosity. Beside, dry rot and scars of ancient hurts confuse the reader of tree rings, and throw him upon estimates, after all. The difficulties III of chopping down a tree io feet in diameter would discourage the most ardent searcher after treasures of fact hid in a tree trunk. A chip a foot deep chopped out of a medium-sized tree-6 feet in diameter—showed an average of fifty-seven years of growth required to make an inch of wood. On soil deposited in the high valleys by glacial rivers these junipers grow about as fast as oaks. They are the well-fed, commonplace members of the family, growing tall and straight under favouring skies.

I cannot forbear a quotation from John Muir's "Forests of the Yosemite Park," for he knows these mountain trees person ally, and has interpreted them to the world as no other man has done: "The sturdy storm-enduring red cedar (Juniperus occi dentalis) delights to dwell on the tops of granite domes and ridges and glacier pavements of the upper pine belt, at an elevation of 7,000 to io,000 feet, where it can get plenty of sunshine and snow and elbow room, without encountering quick-growing, overshadowing rivals. They never make anything like a forest, seldom come together even in groves, but stand out separate and independent in the wind, clinging by slight joints to the rock, living chiefly on snow and thin air, and maintaining tough health on this diet for 2,000 years or more, every feature and gesture expressing steadfast, dogged endurance. . . . Many are mere stumps as broad as high, broken by avalanches and lightning, picturesquely tufted with dense grey scale-like foliage, and giving no hint of dying. . . . Barring accidents, for all I can see, they would live forever. When killed, they waste out of existence about as slowly as granite. Even when overthrown by avalanches, after standing so long, they refuse to lie at rest, leaning stubbornly on theirelbows as if anxious to rise, and while a single root holds to the rocks, putting forth fresh leaves with a grim never-say-die and never-lie-down expression." 112