The Lindens - Family Tiliaceae

No American tree has more abundant foliage than the linden. The branches subdivide into very many twigs, all set with plump buds in winter. These develop into leafy shoots that lengthen rapidly, carrying the broad leaves out where there is room for them to expand fully. A dense shade is cast by this roof of green, and cattle ranging in mixed and open woods are likely to choose this tree as the best shelter from the heat and glare of dog days.

The linden's roots are large and fibrous, penetrating deeply and widely in the soil. The vigour of its growth is not to be wondered at. It is not dependent on transient soil conditions: it draws its sustenance from the deeper sources. Its smooth bark and the lusty symmetry of its frame are revealed in winter. Its lines are gentle curves; its twigs are stout but supple. Its whole character suggests the quality of its wood, which the axe cuts like cheese. Just so the hickory tells by its winter "expression" of the tough fibres its shaggy bark conceals.

The linden opens late in spring. But watch how it makes up time, when the ruby buds do stir, and the inner scales lengthen and reveal the succulent shoots. The flowers wait until the flood of pink and white has subsided in the orchard. Then they open by the hundreds, creamy white and honey laden, and we enjoy them with the bees. Only catalpa and chestnuts will bid for our attention, and the appeal of the fragrance alone is strong enough to lead us to the tree. The blossoms are clustered on dainty pale-green blades. The tree is illuminated, the broad leaf plat forms lined with the delicate inflorescence. A bird flying over looks down upon a tree covered with shingled leaves. It is from underneath that the full beauty of these trees must now be seen.

In midsummer the linden grows coarse. The great leaves are soft and attract hordes of insect enemies. Plant lice cover them with patches of honey dew, and the sticky surfaces catch dust and smoke. Riddled with holes and torn by the wind, they fall in desultory fashion. The faded yellow does not please as does the gold of beech and hickory leaves.

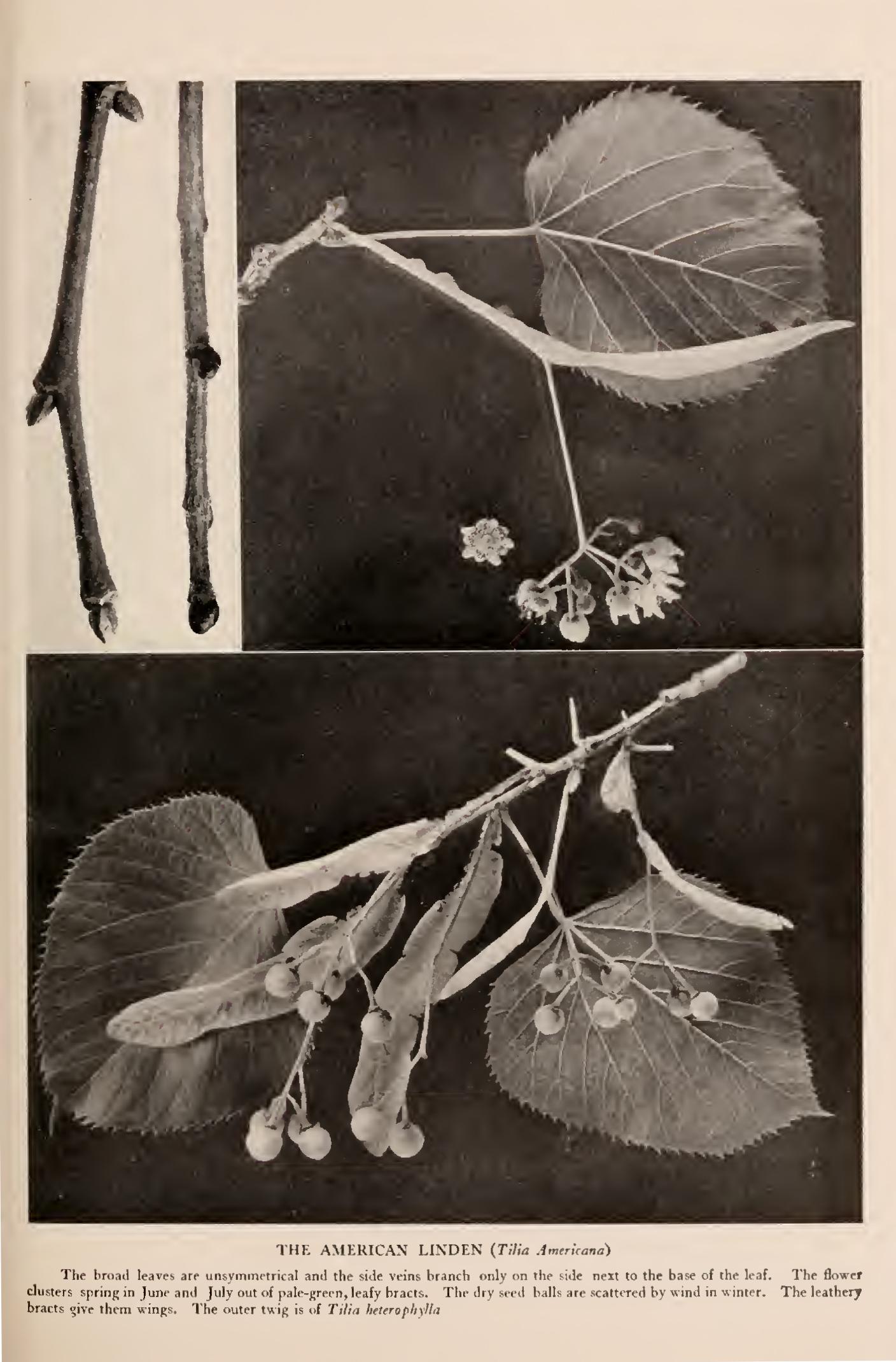

Before they lose their spring freshness, note the linden leaf, so you will always recognise it. The heart-shaped blade is unsym metrical—one half is bigger than the other. The bases do not match, if you fold a leaf on its midrib. Then look at the veining. The main side ribs have large branches only on the lower sides. Those on the other side are simple and small. This is noticeable on no other tree as it is in this one. This peculiarity is seen in the basal half of the leaf, where the side veins are of good size. All lindens show this characteristic. is one of the marked family traits.

In the virgin forests of the Ohio Valley basswoods vastly outnumbered all other trees. The reasons are easy to discover.

Vigorous seeds, winged for flight, are borne in profusion by these trees. Their seedlings are content to grow in the shade. Suckers grow up from the roots of a tree that falls, and every twig the wind tears off is likely to strike root, and soon to become a tree. Only man can interfere with the triumph of such a species in the unceasing battle in the forest. He has distributed Nature's equilibrium. The giant lindens, hundreds of years old, fell under the pioneer's axe, and it will take centuries for the second-growth trees to reach their full stature. Let us hope some of them may be permitted to live their lives undisturbed, just to show to coming generations what the linden trees of the Ohio Valley were in the old days.

The White Basswood, or Bee Tree of the South (Tilia helerophylla, Vent.), is an exceptionally handsome tree, for its bright leaves are pale beneath, often lined with fine, silvery down. As they flutter in the breeze they make a dazzling play of white and pale green against a background usually sombre with hemlocks and mountain laurel.

The white basswood is a lusty forest tree with a preference for the sides of mountain streams. It occurs at Ithaca, New York, and following the Alleghanies south from Pennsylvania, extends to Florida and Alabama, and west to Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee. The leaves are narrower in most cases than those of the Northern species, but they vary in size and form, averaging somewhat larger than those of T. Americana. The fruits are globular, with two seeds in each.

The Downy Basswood (T. pubescens, Ait.), like the Northern species, has leaves that are green on both sides, but this species is distinguished by the rusty hairs that line its leaves and coat its young shoots. It is a small tree, with leaves, flowers and fruits reduced in size. It is a basswood in every character, and need not be confused with the other native species. Its flower blade is rounded at its base, while the others taper narrowly to the short stem.

This little basswood follows the coast from the Carolinas to Texas. It occurs also in Long Island. It is too rare to have any importance as a lumber tree, and it is not a desirable species for cultivation.

A large tree, with pubescent leaf linings and flower stalks, has been discovered growing in various localities from Montreal to Georgia and Texas. Collectors have assigned it to Tilia pubescens, because it is a hairy species. It does not fit the de scription, having larger features throughout, and the seed bract being narrowly obovate, tapering to the base. These may be merely variations from the type species. Professor Sargent accepts Nuttall's name, Tilia Michauxii, in his Manual. The tree is little known as yet.