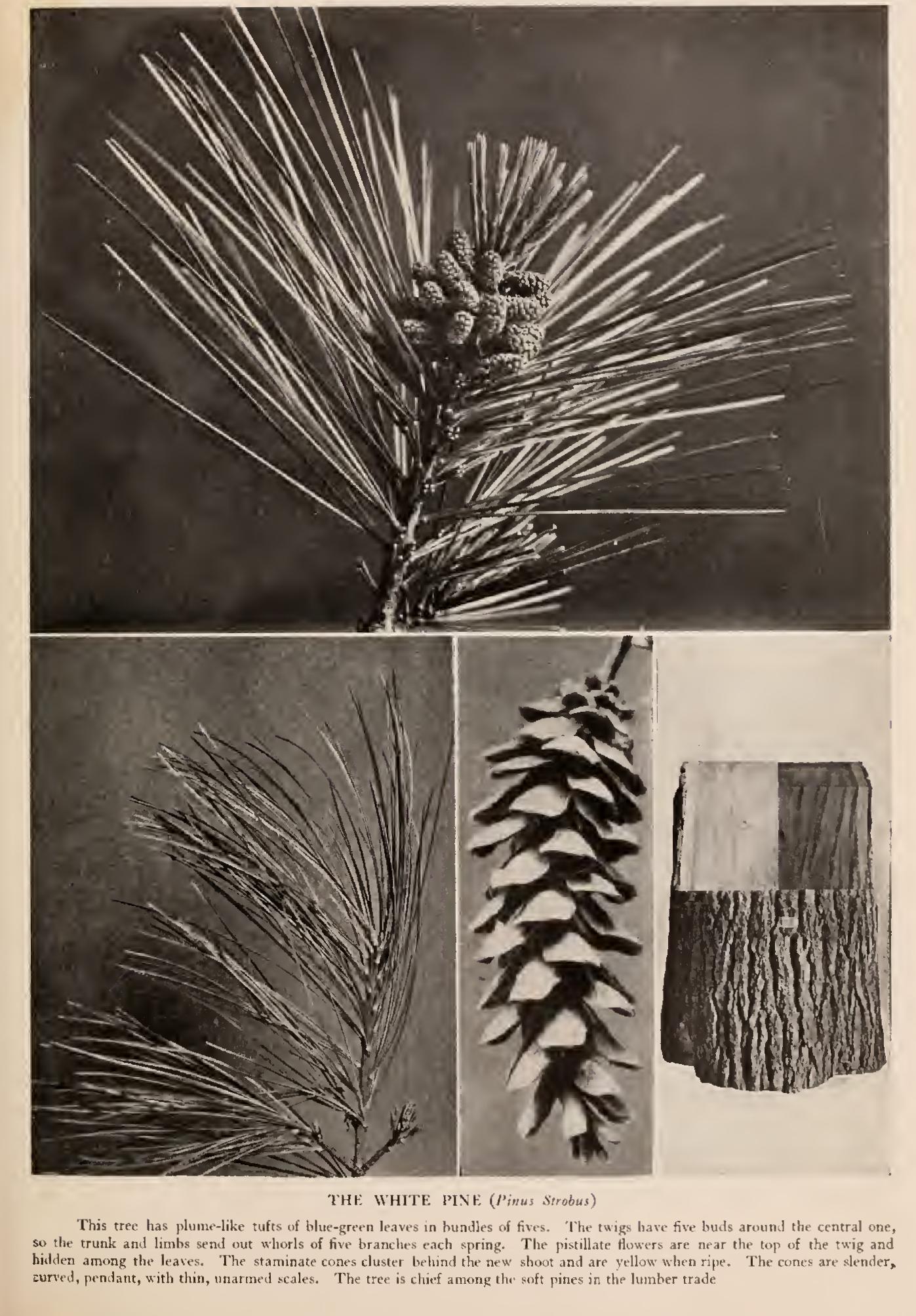

The Soft Pines

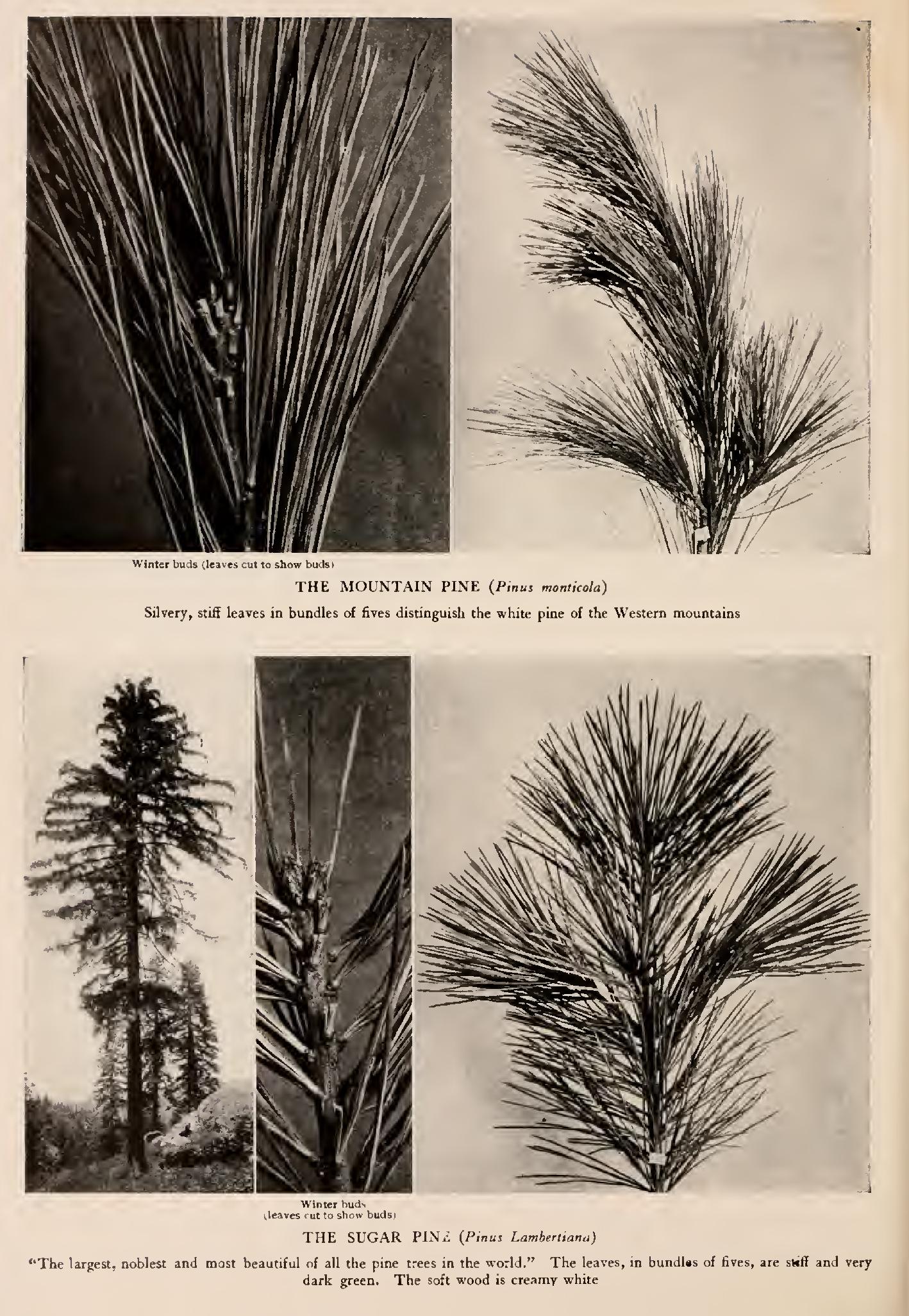

The mountain white pine is the Western counterpart of P. Strobus, which it resembles in general appearance and in the qualities of its wood. Its foliage is denser and its cones nearly twice as large as those of our Eastern white pine, with a beak on each scale that the latter species lacks.

It is unusual, even in the Sierras, to find a tree of gigantic size climbing mountains. This one at the elevation of to,000 feet shows specimens 6 to 8 feet in diameter and 90 feet high, apparently "growing nobler in form and size the colder and balder the mountains about it." The tree companions of this pine crouch at its feet; whatever they may be at lower levels, here they are dwarfs, and only the white pine keeps its noble proportions unmindful of the blasting winds and cold.

P. inonticola surprises and delights the Eastern lover of noble trees, for it submits gracefully to a complete change of altitude and location. Seedlings from veteran trees in their native fast nesses are growing to-day in Eastern nurseries, and thriving on lawns in New England villages. At the Arboretum in Boston the young trees form a narrower pyramid than saplings of P. Strobus at the same age. No Western pine makes as vigorous growth in the East as this one does. A tree 12 feet high bore several cones last year. The species has long been grown in Europe.

Great Sugar Pine (P. Lambertiana, majestic tree, 200 to 220 feet high, 6 to io feet through, pyramidal, be coming flat topped, with spreading, pendulous branches. Bark thick, furrowed, breaking into plates; dark grey, becoming purplish or cinnamon-red. Wood brownish, straight grained, soft, light. Buds pointed, scaly, clustered at tips. Leaves stout, stiff, 3 to 4 inches long, in fives, sheathed, serrate, needle-like, dark green. Flowers much like those of P. Strobus. Fruits 12 to 18 inches long, heavy, scales 2 inches long and 11 inches wide; seeds ripe in second autumn, edible. Preferred habitat, mountain slopes and canon sides. Distribution, coast region in mountains from Oregon into Lower California. Uses : Unsuc cessful in cultivation; lumber used in carpentry, for doors, blinds, sashes, shingles and in cooperage. ap yields sugar.

"The largest, noblest, and mot beautiful of al the seventy or eighty species of pine trees in the world "—thus writes John Muir, who knows the sugar pine of the Sierras as he knows his other neighbours, the mountains and the glaciers, with which he has kept fellowship all his life. Fortunately these gigantic pines do not go down to the sea, nor overhang the banks of seaward tending streams to tempt the lumberman. The hungry mills would have swallowed the best of them long ago had not Nature fenced them in by barriers too great to be overpassed, and the Government has now, by the reservation of the Yosemite National Park, insured the preservation of these mighty pines in sufficient number to remind those who visit the region of what all the Sierra forests were before they were laid waste.

The cones of the sugar pine are the longest known. In spring cone flowers an inch in length stand upright in clusters; they thicken, lengthen and turn down on the coming of the second spring. They are now 2 or 3 inches long, and quite heavy. By September they are close to 2 feet in length and 3 or 4 inches in diameter, pale green, flushing to purple on the side exposed to the sun. High above the earth these cones hang like dangling tassels, none too large for the giant arm that holds them forth. Now the scales spread, and the cone's diameter is doubled. The seeds fall, and are frugally hoarded by squirrels, bears and Indians, for their food value is no secret to any creature that has tasted them. The empty cones hang on the trees until the new crop is ready to harvest, and hard on its heels are the half-grown yearlings, sealed tight to encounter the untried winter weather.

The wood of the sugar pine is the apotheosis of pine lumber. Soft, golden, satiny, fragrant—inviting the woodworker through every one of his senses to handle it. Crystals of sugar accumu late at the end of a stick when it is burning—the bleeding of the heart wood, which gives the trees its name. White masses, crisp and candy-like, gather at axe wounds. It tastes like maple sugar, but one is soon surfeited in eating it.