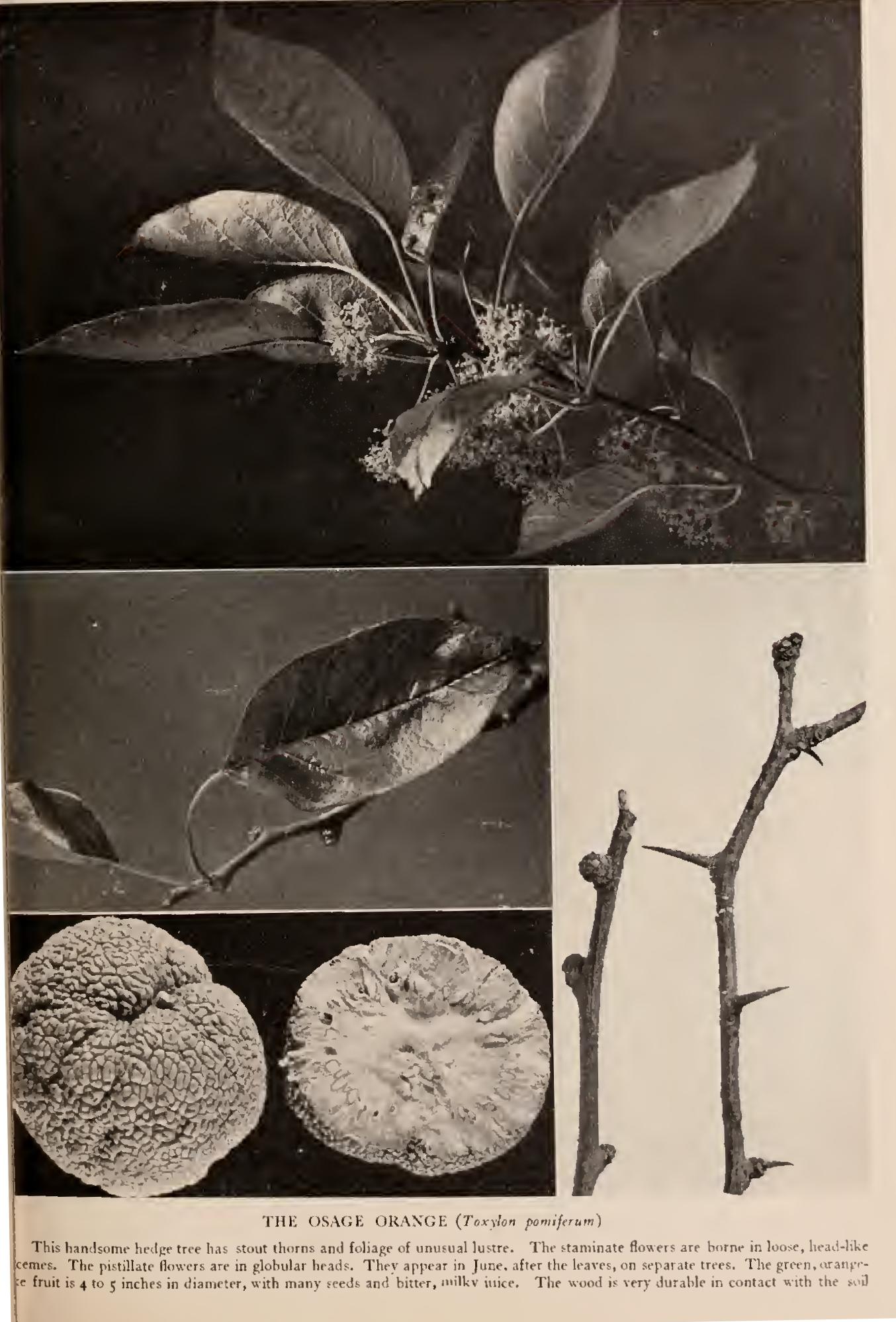

the Osage Orange and the Figs - Family Moraceae the Mulberries

It is a pity that this stock mostly came direct from Arkansas and Texas. A cold winter with little snow killed miles of thrifty hedge, just as it reached the useful stage. Sometimes the roots sent up new shoots, sometimes they didn't, and gaps of varying widths spoiled the appearance and the effectiveness of hedges throughout Illinois, Iowa, Missouri and Kansas. Then barbed wire was introduced, and wicked as it was, it defended the growing crops from free-ranging cattle as no other fencing had done. In most places the hedges were let alone on farm boundaries. These old hedgerows have become an important source of fence posts. No timber furnishes better ones. A row often produces twenty five posts to the rod. These bring from lo cents to 20 cents each in local markets, a fact which makes them a very profitable crop. The native Osage orange timber is all exhausted now; and as the old hedgerows are passing, systematically maintained plantations of Osage orange, grown for posts, promise to pay increasingly well. They ought to be largely planted in the tree's natural range. Occasionally a remnant of the first planting is met with as a fine roadside tree, glorious in its lustrous foliage, formidable thorns, and the remarkable green oranges that hang on the fruiting trees. It is a tree well worth planting for both ornament and shade, for it harbours few insects and has withal a unique character. It is a "foreign-looking" tree.

I had a personal experience with the Osage orange. "The leaves are food for silkworms"—so the nurseryman had told us— and we could have silkworms' eggs from Washington for the asking. Now, gingham aprons were the prevailing fashion for little girls on the Iowa prairies—princesses in fairy tales seemed to wear silks and satins with no particular care as to where they came from. Silkworms and Osage orange offered a combination, and suggested possibilities, which set our imaginations on fire. I .cttuce leaves sufficed for the young caterpillars—then the little mulberry bushes, but the lusty white worms so ghastly naked and dreadful to see, and so ravenous, we fed with Osage orange leaves, cut at the risk of much damage from ugly thorns and with much weari ness. But what were present discomforts compared with the excellency of the hope set before us! Not Solomon in all his glory was arrayed as we expected to be. And the worms—while we loathed them, we counted them, and ministered to their needs.

At last our labours ended. They began to spin, and soon the denuded twigs were thickly studded with the yellow cerements of the translated larva?, to the relief and wonder of all concerned. But even as we wondered, the dead twigs blossomed with white moths whose beauty and tremulous motion passed description. We were lifted into a state of exaltation by the spectacle.

"Whom the gods would destroy they first make mad." A

hard-hearted but well-informed neighbour told us that the broken cocoons were worthless for silk. "You'd ought to have scalded 'em as soon as they spun up." Clouds and thick darkness shut out the day. We refused to be comforted.

This explains why the mere mention of the Osage orange tree, or the sight of a hedge, however thrifty, brings to my mind a haunting suggestion "of old unhappy far-off things." 3. Genus FICUS, Linn.

Figs belong to a genus of 600 species scattered over all tropical countries. The trees have peculiar flowers lining the inside of a fleshy receptacle so that the "fig wasps" that fertilise them have to crawl in through a small opening.

Dried figs are an important commercial fruit. These are from varieties of Ficus Carica, an Asiatic species. Smyrna figs are best for drying. They are extensively raised in California, and cured for market. Other varieties, better adapted for use as a fresh fruit, are grown in many Southern States. The figs we buy are mostly from Asia Minor. The dependence of the fig upon the ministrations of the little wasp is one of the most interesting and baffling chapters in the romance of science.

The rubber plant, vastly popular in this country as a pot plant, is a Ficus. So is the famous banyan tree of India, and the sacred peepul tree of the 1-lindoos. Our native fig trees are sprawl ing parasitic forms, unable to stand alone.

The Golden Fig (F. aurea, Nutt.) climbs up another tree, which it strangles with its coiling stems and aerial roots. There is a famous specimen tree on one of the islands of southern Florida, which has spread by striking root with its drooping branches until it now covers with its secondary trunks an area of a quarter of an acre. It looks much like a banyan tree. More often in South Florida one sees this tree with a sturdy single trunk which has swallowed up the parasite that supported it in youth. Smooth as a beech trunk, with a crown of foliage more glossy than the live oak, this is a large and beautiful tree. The little yellow figs snuggle in the axils of the leaves and turn purple when ripe. They are succulent and sweet, and are sometimes used for jams and preserves.

Another interesting thing about Ficus aurea is that its wood is lighter than that of any other native tree. Its specific gravity is 0.26, which means that, bulk for bulk, this substance is only one-fourth as heavy as water. Most of our woods range between 0.40 and o.80. The heaviest wood belongs also to a Florida tree, Krugiodendron ferreum, Urb., whose specific gravity, when sea soned, is 1.302.

The Poplar-leaf Fig (F. populnea, Willd.) is a rare parasite clambering up other trees on coral islands and reefs off the south ernmost coast of Florida. Its thin, dark green leaves and long 'temmed fruits distinguish it from its near relative.