Writing

sec, century, letters, line, letter, hand, hands, final, comment and position

h. The mediaeval form as a letter ending to the left below the line early acquired a curved link to carry it back to the line in the form of the Sec. often extended in Elizabethan use into an overhead link as in Even without this, it was a long letter, in which the angles tended to become slurred into the shapes Its, and the last being too close to and s°. The It. easily changed into the modern h'.

i and j need little comment, except that their distinctive use for the vowel and consonant (though a few mediaeval instances may be found) is an innovation belonging rather to the history of printing than of writing, and was little observed even by printers till the 17th century. Previous to this, lower case j occurs as the last rather than the first of two or more i's coming together, especially in numerals, as xiij., and in Latin words like conijcio. Dotting of these letters, though well known to mediaeval scribes and obviously useful to distinguish i from a part of m, n, or u, was also not an obligatory process in good writing till the printer set the example.

k, if not much wanted in Latin or Italian is common in Ger manic tongues and the continental form k' competed with the more complicated Sec. and P. More current shapes and le' were liable to confusion with h and b, and is a natural devel opment.

1, m, n, nearly identical in ordinary Sec. and It. forms, need no comment, and of o we need only remark the ambiguity of the negligently formed with open loop, and and p has the characteristic form p' in Elizabethan Sec., later slurred into resembling x'. The It. p2, in the effort to write it cur rently sometimes took the form p3, but a simpler change, by slight opening of the loop, led through to p'.

q needs no comment, but r is another letter of complicated history, and an illustration of the way in which alternative forms have arisen and maintained themselves for centuries. The modern alternatives and have a story reaching back more than a thousand years, the latter originating in the ligature of the uncial letters OR in the shape OZ and thence introduced into minuscule writing, particularly in the common Latin genitive termination orum, written as (094), but admissible anywhere where r follows o. From about the 12th century the use of this 2-shaped r was extended to cases where it followed the letters p and b, the last curve of which is similar to that of o. In the course of the 13th century the analogy of the masculine orum seems to have brought the 2-shaped r into the feminine arum, and in the 74th and 15th century it slowly creeps in after i, e, u and other letters, and last of all as an initial. Normally however, when not following o the form (with longer or shorter shaft) is retained in English as well as It. hands until early in the i6th century, when a short horizontal stroke on the line is introduced, making the typical Sec. form r'. From the short-shafted variety of is developed and from the 2-shape come ?A, and all characteristic of 16th-17th century hands. Several other varieties could be noted if space allowed.

s is another letter of two forms (s and f) the use of which in writing as in print (until about i800) depended on the position of the letter in a word. From aesthetic motives apparently scribes

of the ioth–i2th century gradually discarded the use of the minuscule or long s in a final position and substituted the short or uncial s, which was slowly modified first into a shape like a Greek final sigma s then into something like a medial sigma a, viz., .0 or The use of in an initial position is one of the earliest signs of the popular current hand of about 1300. In Italy the current hand, abandoning the minuscule long s of the formal humanistic script, reverted to the old Roman cursive which it used along with the uncial short We have therefore in Eliza bethan hands the four forms s'–s4 in regular use medially or initially together with the final forms or The addition of fore- and after-links convert and s' into and respectively, but in 17th century hands the one is often shortened or the other lengthened so as to become hardly distinguishable. Slurring of the upper loop converts into but the further development into the modern is scarcely recognized as a copybook form till the 18th century.

t in the regular mediaeval shape had been barely distinguished from The writers of Sec. therefore, influenced, perhaps, by the form in Bastard hand, preferred while is the normal It. In cursive writing and especially in a final position, where slur ring is most prevalent, it took the shapes and is the later development of its medial use.

u needs little comment, except that a practice of distinguishing it from n by adding a curved mark over it, is a fairly sure sign, if not of German or Netherlands, then of Scottish influence.

With regard to the use of u and v the case is similar to that of i and j. Until about 160o, v is merely the initial form of the letter written medially as v. v, w. w' are the Sec. forms.

x. The Sec. form xi closely resembles is the usual It., but occurs before 1600.

y, z. is the Sec. form. z nearly always has a tail.

Of the two surviving extra letters of the Anglo-Saxon (runic) alphabet, the thorn p disappears about the beginning of our period (circ. 1460), being replaced by y in the abbreviations ye and yt for the and that. yok survives a little longer but is often written like z.

The last line of our table shows a few forms of the ampersand, or abbreviation for and (or et). Of other abbreviations common in Elizabethan English few will give much trouble to the reader. The stroke above the line for in or a, r above the line in such words as your (yor) and after aft', p for per or par, and the stroke above for i in the termination cion (our tion), e.g., devocon, deserve notice, as also the sweeping curve for es or s, as in the words lands and ends in the example of Burleigh's hand.

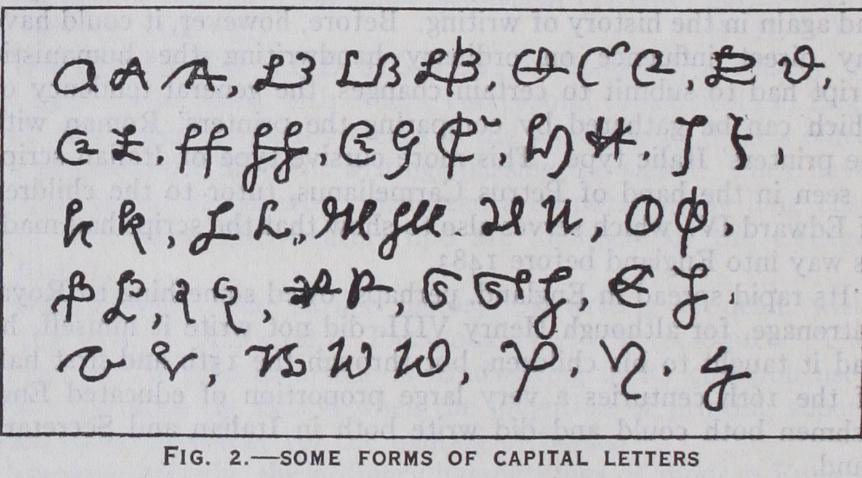

Capital letters have so many forms depending on individual taste, that a detailed analysis in the space at command would be impossible. The very small selection given includes some of the Elizabethan forms which are most different from modern usage. For bibliography see CALLIGRAPHY.