Joints and Ligaments

joint, bones, cavity, fig, movable, movement and cartilage

JOINTS AND LIGAMENTS. Anatomically a joint is any connection between two or more adjacent parts of the skeleton, whether they be bone or cartilage. Joints may be immovable, like those of the skull, or movable, like the knee.

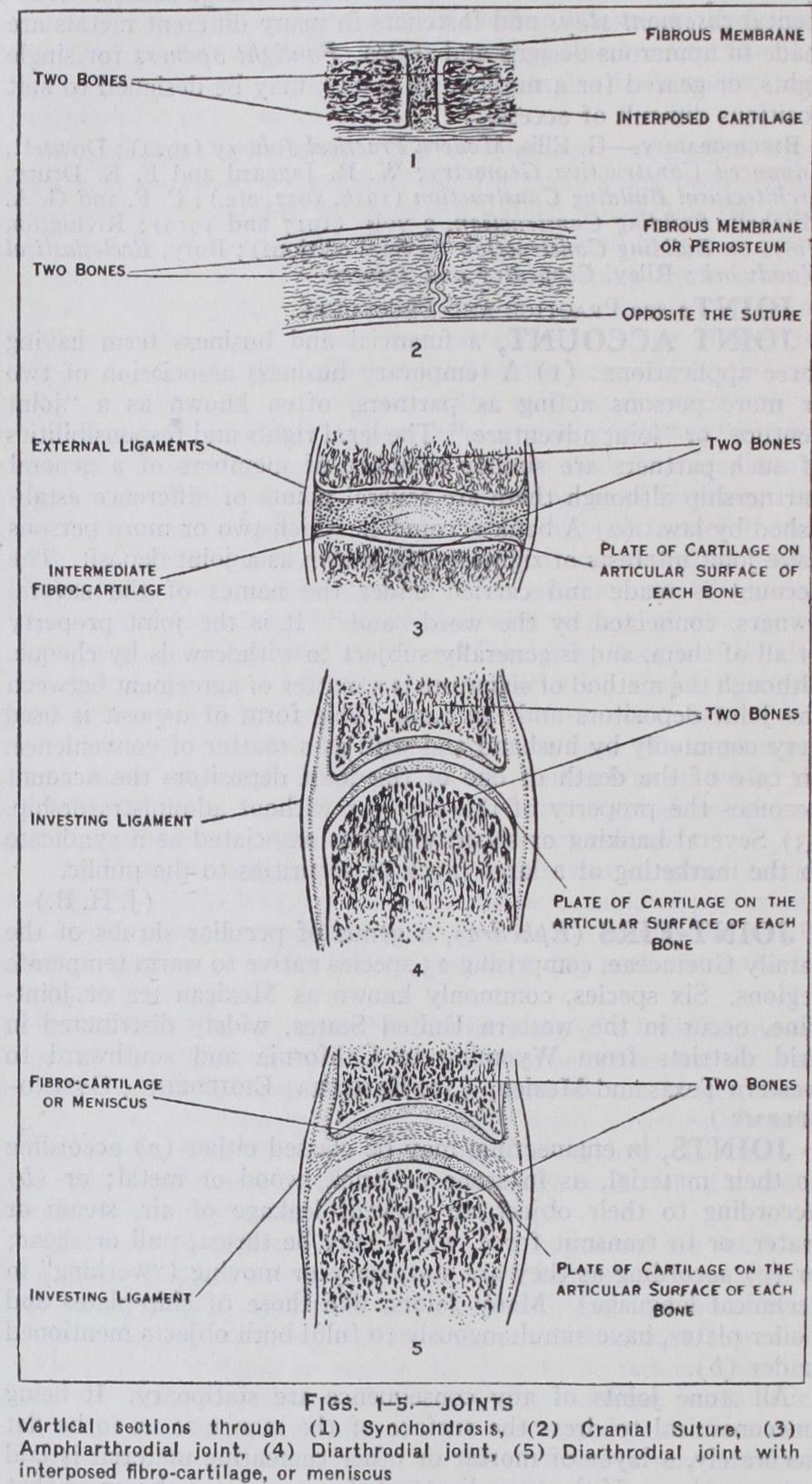

Immovable joints (synarthroses) are adaptations to growth and are always between bones. When growth ceases the bones often unite (synostosis). Immovable joints never have a cavity between the two bones ; there is simply an unaltered layer of the substance in which the bone has been laid down. If the bone is being deposited in cartilage, a layer of cartilage intervenes, and the joint is called synchondrosis (fig. 1), but if in membrane, a thin layer of fibrous tissue persists, and the joint is then known as a suture (fig. 2). Good examples of synchondroses are the epiphysial lines separating the epiphyses from the shafts of de veloping long bones, or the occipito-sphenoid synchondrosis in the base of the skull. Examples of sutures are plentiful in the vault of the skull. There are two kinds of fibrous synarthroses, which differ from sutures in that they do not synostose. One of these is a schindylesis, in which a thin plate of one bone is received into a slot in another, as in the joint between the sphenoid and vomer. The other is a peg and socket joint, or gomphosis, found where the fangs of the teeth fit into the alveoli or tooth sockets in the jaws.

Movable joints (diarthroses) are divided into those in which there is much and little movement. When there is little move ment the term half-joint or amphiarthrosis is used. The simplest kind of amphiarthrosis is that in which two bones are connected by bundles of fibrous tissue which pass at right angles from the one to the other; such a joint differs from a suture by the facts that the intervening fibrous tissue is organized into bundles (interosseous ligaments), and that it does not synostose when growth stops. A joint of this kind (syndesmosis) depends upon the amount of movement which is brought about by the muscles on the two bones. As an instance of this the inferior tibiofibular joint of mammals may be cited. In man this is a syndesmosis, and there is only a slight play between the two bones. In the mouse there is no movement, and the two bones form a syn chondrosis between them which speedily becomes a synostosis, while in many Marsupials there is free mobility between the tibia and fibula, and a definite synovial cavity is established. The

other variety of amphiarthrosis or half-joint is the symphysis, which differs from the syndesmosis in having both bony surfaces lined with cartilage and between the two cartilages a layer of fibro-cartilage, the centre of which often softens and forms a small synovial cavity. Examples of this are the symphysis pubis, the mesosternal joint, and the joints between the bodies of the vertebrae (fig. 3).

The true diarthroses are joints in which there is free movement. The opposing surfaces of the bones are lined with the unossified remnant of the cartilaginous model in which they are formed (fig. 4). Between the two cartilages is the joint cavity, while sur rounding the joint is the capsule (fig. 4), which is formed chief ly by the superficial layers of the original periosteum or peri chondrium, perhaps strengthened externally by tendinous inser tions of muscles. The greater the intermittent strain on any part of the capsule the thicker it Lining the interior of the capsule, and all other parts of the joint cavity except where the articular cartilage is present, is the synovial membrane (fig. 4, dotted line) ; this is a layer of endothelial cells which secrete the synovial fluid to lubricate the interior of the joint.

A compound diarthrodial joint is one in which the joint cavity is divided partly or wholly into two by a meniscus or inter-articu lar fibro-cartilage (fig. 5).

The shape of the joint cavity varies greatly, and the different divisions of movable joints depend upon it. It is often assumed that the structure of a joint determines its movement, but the converse view has much in its favour. Thus, the mobility of the metacarpo-phalangeal joint of the thumb in many working men is less than it is in many women who use needles and thread, or in many medical students who use pens and scalpels, and the slight ly movable thumb has quite a differently shaped articular sur face from the freely movable one (see J. Anat. and Phys., xxix., 446).