Kinetic Theory of Matter

atoms, molecules, salt, common, molecule and motion

KINETIC THEORY OF MATTER. The kinetic theory of matter rests upon two distinct, but closely related hypotheses, the hypothesis of the molecular structure of matter and the hypothesis that heat is a manifestation of the random to-and-from motion of the molecules.

The hypothesis of the molecular structure of matter forms the basis of the science of chemistry (see CHEMISTRY). A mass of a given chemical substance, say common salt (chloride of sodium) or water (oxide of hydrogen) consists of a number of exactly similar molecules. All the chemical properties of common salt or of water are inherent in a single molecule of the substance, so that it is proper to speak of a molecule of salt or a molecule of water. The molecule is the smallest unit of which this is true; it is possible by chemical and electrical means to divide a molecule of common salt into two atoms, but these no longer have the chemical properties of common salt ; indeed they are not-common salt at all, one being an atom of sodium and the other being an atom of chlorine.

Molecular Motion.

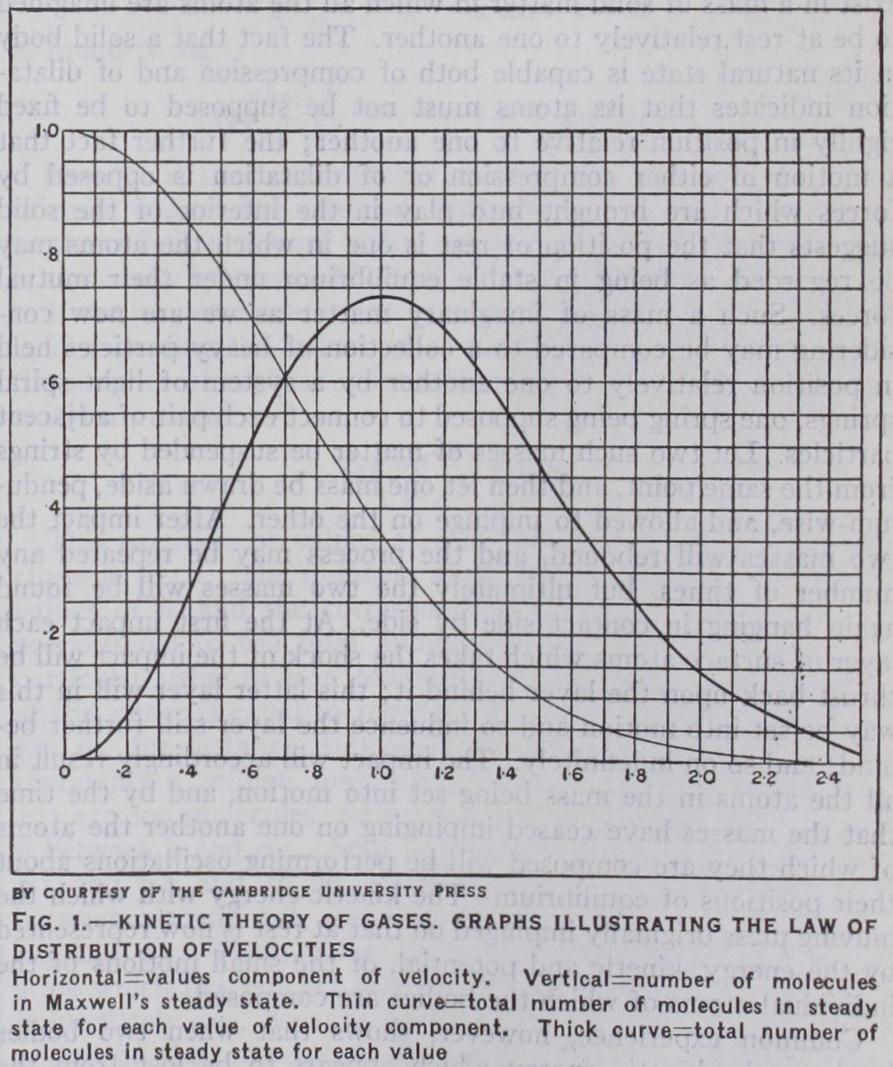

The hypothesis that heat arises from the motions of the molecules of a substance, each moving as an independent unit, is based upon a large mass of observational evidence, the most convincing of which, perhaps, is that the re sults of the kinetic theory of matter, all of which would be fallacious if this hypothesis were not true, are found to be in excellent agreement with observation. In some cases the heat motion does not consist solely of molecular motion, the motions of the atoms inside the molecules contributing a large part of the heat of the substance. Roughly speaking, heat-motion is found to assume three distinct forms which correspond to the three dis tinct states in which matter can exist, the solid, liquid and gaseous.

Modern research on the crystalline structure of solids has made it clear that in a solid the atoms form independent units, and that the heat motion is not a motion of complete molecules but of complete atoms only. In a sense there are no molecules

in a solid. In a mass of common salt the atoms of sodium alter nate with the atoms of chlorine, but a given atom of sodium is no more closely associated with the atom of chlorine on its right than with that on its left, and any division of the salt into mole cules of sodium chloride can only be arbitrary and artificial. The same general conclusion emerges from a study of the specific heats of solids; these show that the atoms, and not the molecules, are the independently moving units. The distances traversed by the atoms of a solid are very small in extent, as is shown by in numerable facts of everyday observation. For instance, the sur face of a finely-carved metal (such as a plate used for steel engraving) will retain its exact shape for centuries, and again, when a metal body is coated with gold-leaf, the atoms of the gold remain on its surface indefinitely ; if they moved through any but the smallest distances they would soon become mixed with the atoms of the baser metal and diffused through its interior. Thus the atoms of a solid can only make small excursions about their mean positions.

In a gas the state of things is very different ; an odour is known to spread rapidly through great distances, even in the stillest air, and a gaseous poison or corrosive not only attacks those objects which are in contact with its source, but all those which can be reached by the motion of its moving parts. Common observation shows that these moving parts are com plete molecules ; the atoms do not travel separately. For instance the molecule of ammonia vapour consists of four atoms : three of hydrogen and one of nitrogen. Neither hydrogen nor nitrogen has any perceptible odour, yet on spilling ammonia we are greeted with an extremely pungent smell. This is the smell neither of hydrogen nor of nitrogen nor a mixture of the two smells ; it is the characteristic smell of ammonia which is produced only by complete molecules of the substance.