John of Gaunt Lancaster

castile, england, henry, home, married, daughter, france, aquitaine, pedro and king

LANCASTER, JOHN OF GAUNT, DUKE OF '399), fourth son of Edward III. and Queen Philippa, was born in March 134o at Ghent, whence his name. On Sept. 29, 1342, he was made earl of Richmond; as a child he was present at the sea fight with the Spaniards in August 135o, and his military service was in 1355, when he was knighted. On May 19, 1359, he married his cousin Blanche, daughter and ultimately sole heiress of Henry, duke of Lancaster. In her right he became earl of Lancaster in 1361, and next year was created duke. His marriage made him the greatest lord in England, but for some time he took no prominent part in public affairs. In 1366 he joined his eldest brother, Edward the Black Prince, in Aquitaine, and in the year after led a strong contingent to share in the campaign in support of Pedro the Cruel of Castile. With this began his long connection with Spain. John fought in the van at Najera on April 13, 1367, when the English victory restored Pedro to his throne. He re turned home at the end of the year. Pedro was finally overthrown and killed by his rival, Henry of Trastamara, in 1369. The dis astrous Spanish enterprise led directly to renewed war between France and England.

In August 1369 John had command of an army which invaded northern France without success. In the following year he went again to Aquitaine, and was present with the Black Prince at the sack of Limoges. Edward's health was broken down, and he soon after went home, leaving John as his lieutenant. For a year John maintained the war at his own cost. His wife died in the autumn of 1369 and John married Constance (d. 1394), the elder daughter of Pedro the Cruel, and in her right assumed the title of king of Castile and Leon. For sixteen years the pursuit of his kingdom was the chief object of John's ambition. No doubt he hoped to achieve his end, when he commanded the great army which invaded France in 1373. But the French would not give battle, and though John marched from Calais right through Champagne, Burgundy and Auvergne, it was with disastrous results ; only a shattered remnant of the host reached Bordeaux.

When John got back to England he was soon absorbed in domes tic politics. The king was prematurely old, the Black Prince's health was broken. John, as head of the court party, had to bear the brunt of the attack on the administration made by the Good Parliament in 1376. As soon as the parliament was dissolved he had its proceedings reversed, and next year secured a more sub servient assembly. There came, however, a new development. The duke's politics were opposed by the chief ecclesiastics, and in resisting them he had made use of Wycliffe. With Wycliffe's religious opinions he had no sympathy. Nevertheless when the bishops arraigned the reformer for heresy John would not aban don him. The conflict over the trial led to a violent quarrel with the Londoners, and a riot in the city during which John was in danger of his life from the angry citizens. The situation was entirely altered by the death of Edward III. Though his enemies had accused him of aiming at the throne, John was without any taint of disloyalty. Though he took his proper place in the cere monies at Richard's coronation, he withdrew for a time from any share in the government. In 1378, he commanded in an unsuccess ful attack on St. Malo. During his absence some of his supporters

violated the ranctuary at Westminster. He vindicated himself somewhat bitterly in a parliament at Gloucester, and accepted the command on the Scottish border. He was there engaged when his palace of the Savoy in London was burnt during the peasants' revolt in June 1381. Against his will he was forced into an unfor tunate campaign on the Scottish border in 1384. His ill-success renewed his unpopularity, and the court favourites of Richard II. intrigued against him. Finally the difficulties of his position at home strengthened his foreign ambitions.

Spanish Expedition.-In

July 1386 John left England with a strong force to win his Spanish throne. He landed at Corunna, and during the autumn conquered Galicia. Juan, who had suc ceeded his father Henry as king of Castile, offered a compro mise by marriage. John of Gaunt refused, hoping for greater success with the help of the king of Portugal, who now married the duke's eldest daughter Philippa. In the spring the allies invaded Castile. They could achieve no success, and sickness ruined the English army. The conquests of the previous year were lost, and when Juan renewed his offers, John of Gaunt agreed to sur render his claims to his daughter by Constance of Castile, who was to marry Juan's heir. After some delay the peace was con cluded at Bayonne in 1388. The next eighteen months were spent by John as lieutenant of Aquitaine, and it was not till November 138g that he returned to England.

By his absence he had avoided implication in the troubles at home. Richard, still insecure of his own position, welcomed his uncle, and created him duke of Aquitaine. During four years John exercised his influence in favour of pacification at home, and abroad was chiefly responsible for the conclusion of a truce with France. Then in 1395 he went to take up the government of his duchy; but the Gascons had from the first objected to government except by the crown, and secured his recall within less than a year. Constance of Castile had died in 1394 and almost immediately after his return John married as his third wife Catherine Swyn ford. Catherine had been his mistress for many years, and his children by her, who bore the name of Beaufort, were now legiti mated. Though John presided at the trial of the earl of Arundel in September 1397, he took no further active part in affairs. The exile of his son Henry in 1398 was a blow from which he did not recover. He died on Feb. 3, 1399, and was buried in St. Paul's cathedral near the high altar.

John was neither a great soldier nor a statesman, but he was a chivalrous knight and loyal to what he believed were the interests of his family. In spite of opportunities and provocations he never lent himself to treason. He deserves credit for his protection of Wycliffe, though he had no sympathy with his religious or politi cal opinions. He was also the patron of Chaucer, whose Boke of the Duchesse was a lament for Blanche of Lancaster.

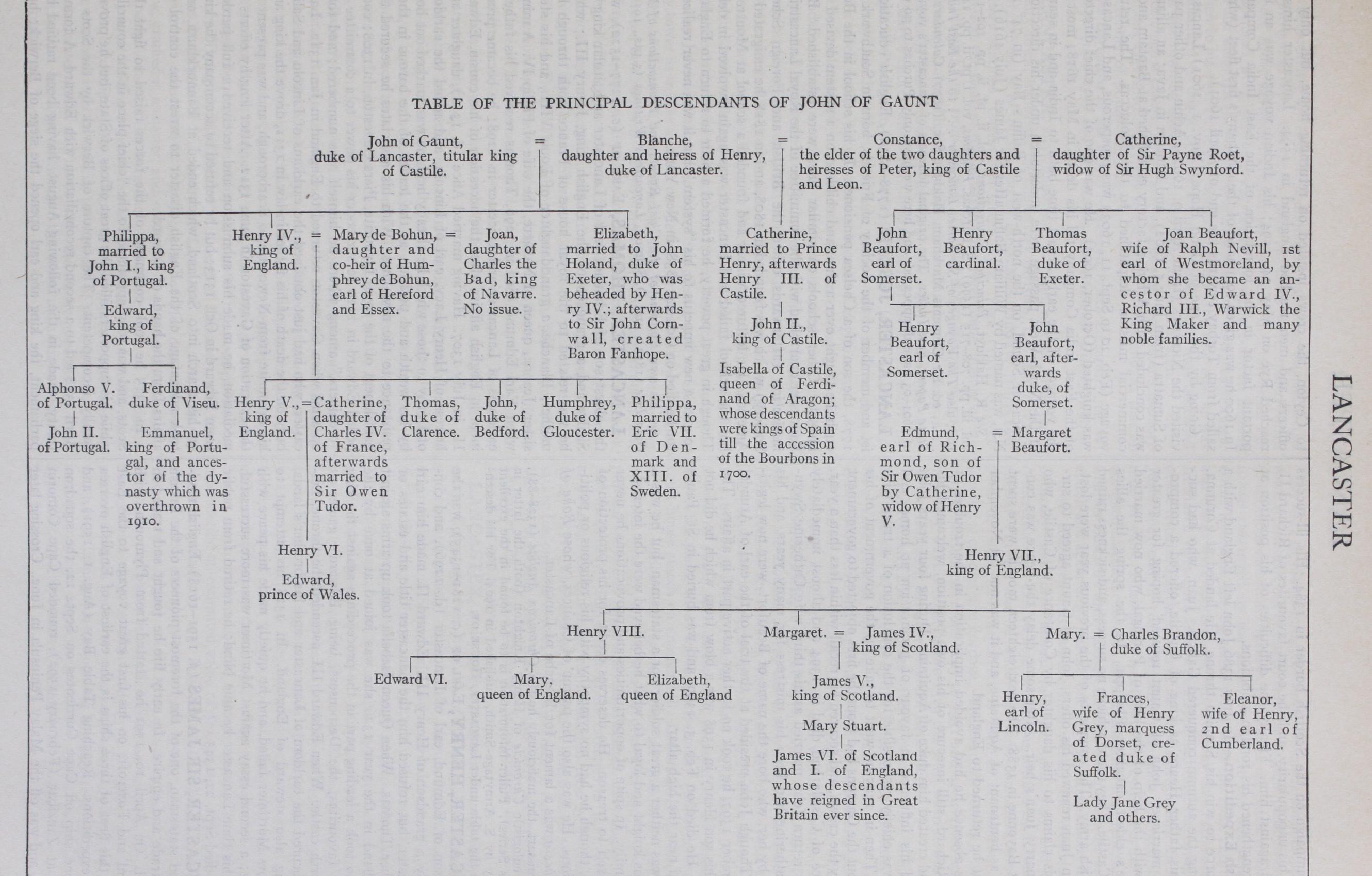

See Froissart, the maliciously hostile Chronicon Angliae (1328-88), and the eulogistic Chronicle of Henry Knighton (both the latter in the Rolls Series). Fuller information is to be found in the excellent biography by S. Armytage-Smith, published in 1904. For his descen dants see the table under LANCASTER, HOUSE OF.