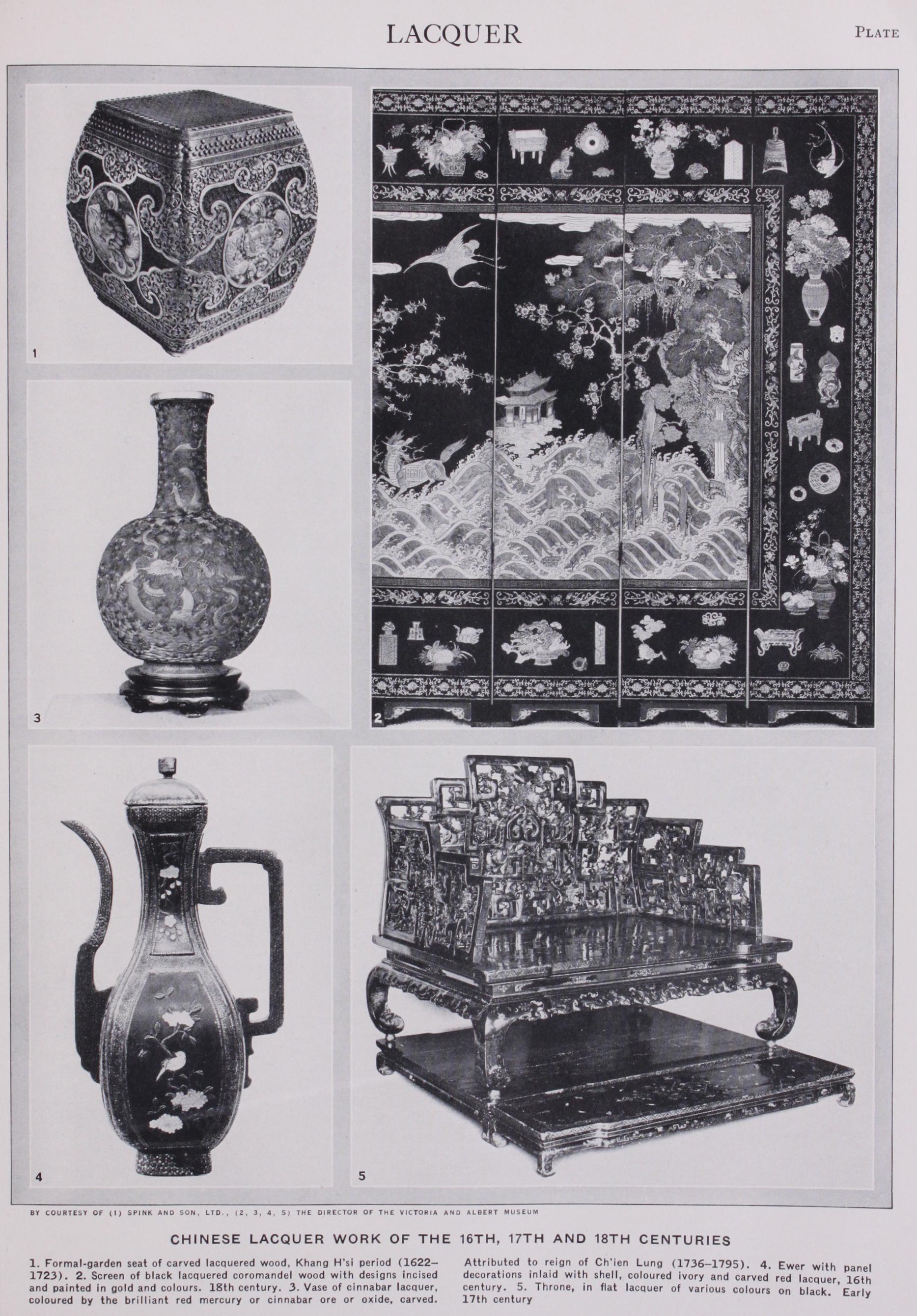

Lacquer or Lacker

japan, wood, china, sap, applied, basis, processes, coat, laid and white

LACQUER or LACKER, a general term for coloured and frequently opaque varnishes applied to certain metallic objects and to wood. The term is derived from the resin lac, which sub stance is the basis of lacquers properly so-called. Technically, among Western nations, lacquering is restricted to the coating of polished metals or metallic surfaces, such as brass, pewter and tin, with prepared varnishes which will give them a golden, bronze-like or other lustre as desired. Throughout the East Indies lacquering of wooden surfaces is practised, articles of household furniture, as well as boxes, trays and toys, being deco rated with bright-coloured lacquer. This process of applying the lacquer to decorative articles of wood is also known as Japanning.

The lacquer of the Far East, China, Japan and Korea must not be confused with other substances to which the term is generally applied ; for instance, the lac of Burma, which is the gummy de posit of an insect, Coccus Lacca, and the various solutions of gums or resin in turpentine of which European imitations of Eastern lacquer have been and are concocted.

Lacquer, properly so-called and as used in China and Japan, is a natural product, the sap of a tree, Rhus V ernicifera; subject to the removal of impurities and excess water, it can be used in its natural state, though it was frequently adulterated. The tree, which is indigenous to China, and has certainly been cultivated in Japan at least since the 6th century A.D., is tapped at about the age of ten years, lateral incisions being made in the bark and the running sap collected during the months of June to September. Branches of a diameter of one inch or more are also tapped, the bark having first been removed. Smaller branches are cut off, soaked in water for ten days, and the sap collected, producing a lacquer (seshime) of particular quality, used for special pur poses. These processes kill the tree, but the wood, when of suffi cient size, is of some use for carpentry. From the roots five or six shoots spring up, which become available for the production of lacquer after about six years, and the operation can be thus continued for a considerable length of time before the growth is exhausted. The Chinese and Japanese methods are practically identical in this respect, but the cultivation of the tree does not seem to have been so systematic in China as in Japan. The sap, when extracted, is white or greyish in colour and about the con sistency of treacle. On exposure to the air it turns yellow-brown and then black. It is strained through hempen cloth to remove physical impurities, after being pounded and stirred in shallow wooden tubs, to give it uniform liquidity. It is then slightly heated over a slow fire or in hot sunshine and stirred again to evaporate excess moisture, and stored in air-tight vessels. The characteristic constituent of lacquer is termed by chemists urushiol (from the Japanese name of lacquer, urushi), and its formula has been stated as C14111802. Japanese lacquer is said by Prof. K. Mijama to contain from 64.00 to 77.6% of urushiol as compared with an average of 55.84 for Chinese; the difference being due, probably, to inferior methods of cultivation and extraction, and perhaps in some cases to climatic differences. Lacquer is a slightly irritant poison, but workers in the industry soon become inoculated. A series of implements used in the preparation of lacquer with an illustration of the system employed in the actual gathering of the sap is exhibited in Museum No. i of the Royal Botanic gardens, Kew, England.

Lacquer-ware.

The basis of lacquer-ware, both in Japan and in China, is almost always wood, although it was also occa sionally applied to porcelain and brass and white metal alloys. Insome instances, objects were carved out of solid lacquer. The wood used, generally a sort of pine having a soft and even grain, was worked to an astonishing thinness. The processes that follow are the result of extraordinary qualities of lacquer itself, which, on exposure to air, takes on an extreme but not brittle hardness, and is capable of receiving a brilliant polish of such a nature as to rival even the surface of highly glazed porcelain. Moreover, it has the peculiar characteristic of attaining its maximum hardness in the presence of moisture. The Japanese, therefore, place the object, to secure this result, in a damp box or chamber after each application of lacquer to the basic material (wood, etc.). The Chinese are said (in an account of the industry dating from A.D. 1621-28) to use a "cave" in the ground for this purpose, and to place the objects therein at night in order to take advantage of the cool night air. It may, indeed, be said that lacquer dries in a moist atmosphere. The joiner's work having been completed, and all knots or projections having been most carefully smoothed away, cracks and joints are luted with a mixture of rice paste and seshime lacquer, till an absolutely even surface is obtained. It is then given a thin coat of seshime lacquer to fill up the pores of the wood and to provide a basis for succeeding operations : in the case of fine lacquer, possibly as many as 20 or 3o or even more ; of each of which the following may be taken as typical. On the basis, as above described, is laid a coat of lacquer composition, allowed to harden, and ground smooth with whetstone. Next comes a further coat of finer composition, in which is mixed some burnt clay, which is again ground, and laid aside to harden for at least 12 hours. On this is fixed a coat of hempen cloth (or rarely in Japan, but more often in China, paper) by means of an ad hesive paste of wheat or rice flour and lacquer, which needs hours at least to dry. The cloth is smoothed with a knife, and then receives several successive coats of lacquer composition, each demanding the delay necessary for hardening. On this is laid very hard lacquer, requiring a much longer drying interval, afterwards being ground to a fine surface. Succeeding coats of lacquer of varying quality are now laid on, dried and polished; and this preliminary work, occupying in the case of artistic lacquer-work at least 18 days, produces the surface on which the artist in lacquer begins his task of decoration. A large number of processes were at his command, especially in Japan, but the design was first generally made on paper with their lacquer and transferred to the object while still wet, or drawn on it direct with a thin paste of white lead or colour. In carrying it out he made use of gold or silver dust applied through a quill or bamboo tube, or through a sieve to secure equal distribution. Larger fragments of the precious metals (hirame or kirikane) were applied separately by hand, with the aid of a small, pointed tool. In one typical instance the writer has counted approximately Soo squares of thin gold foil thus inserted, within one square inch. These decorative processes each entailed prolonged hardening periods and meticulous polishing. Relief was obtained by modelling with a putty consisting of a mixture of lacquer with fine charcoal, white lead, lamp-black, etc., camphor being added to make it work easily. Lacquer was sometimes engraved, both in China and Japan.