Lhasa

city, tibet, chief, centre, houses, ridge and dogs

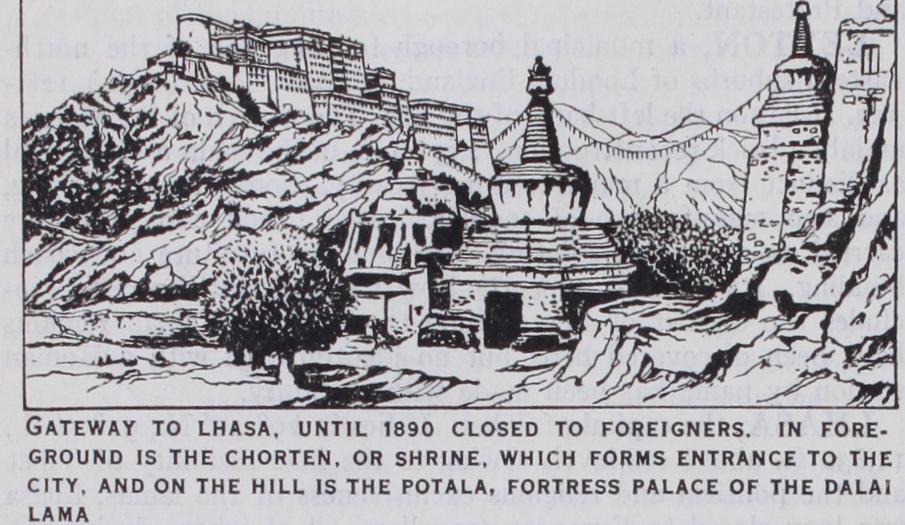

LHASA, the capital of Tibet. It lies in 29° 39' N., 91° 5' E., 11,830 ft. above sea-level. Owing to the inaccessibility of Tibet and the political and religious exclusiveness of the lamas, Lhasa was long closed to European travellers, all of whom during the latter half of the 19th century were stopped in their attempts to reach it. It was popularly known as the "Forbidden City." But its chief features were known by the accounts of the earlier Roman Catholic missionaries who visited it and by the investiga tions, in modern times, of native Indian secret explorers, and others, and the British armed mission of 1904. (See TIBET.) Site and General Aspect.—The city stands in a tolerably level plain, which is surrounded on all sides by hills. Along its southern side, about m. south of Lhasa, runs a considerable river called the Kyichu (Ki-chu) or Kyi, flowing here from the east-north-east, and joining the great Tsangpo (or upper course of the Brahmaputra) some 38 m. to the south-west. The hills round the city are barren. The plain, however, is fertile, though in parts marshy. There are gardens scattered over it round the city, and these are planted with fine trees. The city is screened from view from the west by a rocky ridge, lofty and narrow, with summits at the north and south, the one flanked and crowned by the majestic buildings of Potala, the chief residence of the Dalai lama, the other by the temple of medicine. Groves, gardens and open ground intervene between this ridge and the city itself for a distance of about 1 m. A gate through the centre of the ridge gives access from the west ; the road thence to the north part of the city throws off a branch to the Yutok sampa or turquoise tiled covered bridge, one of the noted features of Lhasa, which crosses a former channel of the Kyi, and carries the road to the centre of the town.

The city is nearly circular in form, and less than r m. in diameter. It was walled in the latter part of the 17th century, but the walls were destroyed during the Chinese occupation in 1722. The chief streets are fairly straight, but generally of no great width. There is no paving or metal, nor any drainage system, so that the streets are dirty and in parts often flooded.

The inferior quarters are unspeakably filthy, and are rife with evil smells and large mangy dogs and pigs. Many of the houses are of clay and sun-dried brick, but those of the richer people are of stone and brick. All are frequently white-washed, the doors and windows being framed in bands of red and yellow. In the suburbs there are houses entirely built of the horns of sheep and oxen set in clay mortar. This construction is in some cases very roughly carried out, but in others it is solid and highly picturesque. Some of the inferior huts of this type are inhabited by the Ragyaba or scavengers, whose chief occupation is that of disposing of corpses according to the practice of cutting and ex posing them to the dogs and birds of prey. The houses generally are of two or three storeys. Externally the lower part generally presents dead walls (the ground floor being occupied by stables and similar apartments) ; above these rise tiers of large windows with or without projecting balconies, and over all flat broad eaved roofs at varying levels. In the better houses there are often spacious and well-finished apartments, and the principal halls, the verandahs and terraces are often highly ornamented in brilliant colours. In every house there is a kind of chapel or shrine, carved and gilt, on which are set images and sacred books.

Temples and Monasteries.

In the centre of the city is an open square which forms the chief market-place. Here is the great temple of the ''Jo" or Lord Buddha, called the Jokhang, regarded as the centre of all Tibet, from which all the main roads are considered to radiate. This is the great metropolitan sanctu ary and church-centre of Tibet, the St. Peter's or Lateran of Lamaism. It is believed to have been founded by the Tibetan Constantine, Srong-tsan-gampo, in 652, as the shrine of one of those two very sacred Buddhist images which were associated with his conversion and with the foundation of the civilized mon archy in Tibet. The exterior of the building is not impressive; it rises little above the level of other buildings which closely surround it, and the effect of its characteristic gilt roof, though conspicuous and striking from afar, is lost close at hand.