Ture a F Br

garden, city, roof, house, architectural, wide, conditions, background, space and paths

Usually the geometrically planned garden is most satisfactory in a town. It is difficult to make 4o by soft. into a miniature yet complete piece of wilderness, and it becomes impossible if a garage, a clothes-line or intensive cultivation of vegetables has a place in the scheme. The necessity of developing the plan logically cannot be stressed too strongly. A common and usually incorrect way to lay out a garden is to divide the available space by placing paths at right angles to each other ; through the windows of the house such paths generally seem to begin and lead nowhere; the beds left by such arrangement are of sizes unsuited both to easy cultivation and to treatment in a pleasing manner. What matters least in the layout of a garden is its being symmetrical about a centre line, what is most important is to have the openings of the house opposite the axes of the garden regardless of whether they are on the physical centre of the garden space or not. While a plan on paper may appear lop-sided, in the garden itself, with varying heights and masses of planting to produce effects, it can appear well proportioned if not equally divided. Extending the axes of the house into the garden does not mean that the back door must open on a garden path. The garden may lie across a stretch of unbroken lawn with no path leading from porch or door to its entrance, but the entrance should be centred on a door or porch or window so that its connection with the house is at once apparent. Most amateur gardeners fail to recognize this point, and many otherwise charming gardens lose effectiveness because this prin ciple has been neglected.

Having observed how the planting and surroundings will throw shadows, what unsightly objects must be screened, and the views of the garden from the house; having decided whether to have lawn, flowers, vegetables or all three—sketches may be made to evolve the plan best suited to all conditions involved. The designer has to decide how wide and how long to make the paths and flower borders so that they will be in proportion to the garden as a whole. Generally speaking the flower borders should be at least half again as wide as the paths—twice as wide being a better proportion—and the paths should be as wide as the whole space will permit up to five feet. Five feet is a pleasant and comfortable width in which two people may walk abreast, but if the space is so restricted that five-foot paths swallow up and dwarf the garden, it is better to reduce them to three or even to two and a half. The size of the architectural details, ornaments or accessories, such as a sundial, a fountain or bench, must be carefully considered in their relation to the size of the garden, so that they will not dwarf it by being too large or appear ridiculous because they are too small.

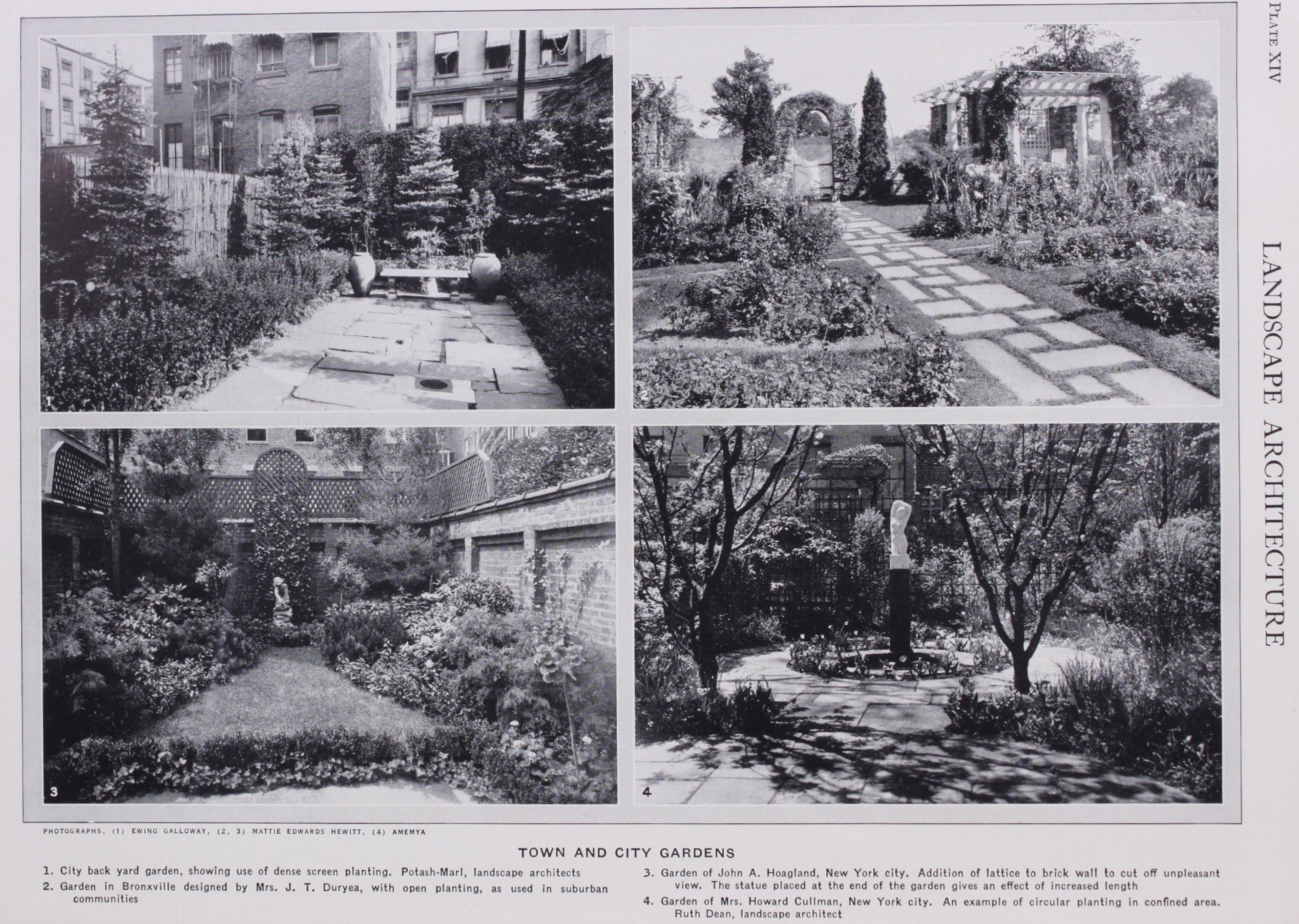

Since the average city plot is 20 by iooft. and the house con sumes the whole width and at least half the depth, very little land is left on which to make a garden. Further, the amount of sun light is so limited and the constant rain of soot so damaging to the vegetation that few plants will grow. No conifers are able to sur vive the atmospheric conditions because they exude a resinous gum, which glues the soot fast, clogging their pores and killing them ; but a few broad-leaved evergreens whose hard glossy leaves shed dirt easily, will live. In the temperate zone rhododendrons, Japanese holly (Ilex crenata), andromeda japonica, aspidistra and English ivy all do surprisingly well under these hard conditions, and of course privet and the ailanthus tree are known for their persistence in living under almost any conditions. Flowers, for the most part, are pathetic objects in the big city garden; a few of the hardier perennials, such as German iris and chrysanthemums, struggle through, but to have colour in a city garden it is neces sary to have freshpotted plants every two or three weeks. As

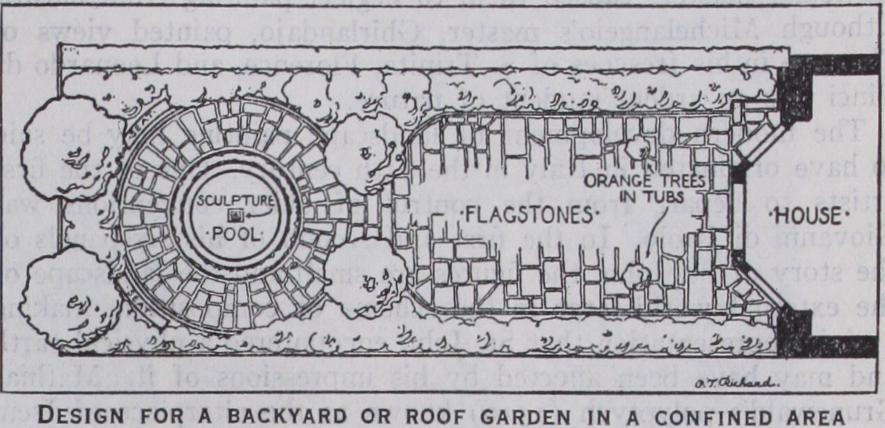

vegetation is so uncertain, the city garden is much more dependent on an architectural background and accessories than the suburban one where luxuriant foliage and flowers are possible. Under the best conditions the city garden cannot wholly mask or distract attention from the artificial elements by a wealth of blossoms. This means that walls, trellises, walks, fountains and seats must be so well designed as to create the atmosphere of a garden even though foliage is largely absent. A garden of this type in New York city is shown in the following plan, and although the size of the garden is only 20 by 4oft. it appears larger because the two Japanese flowering cherries in the foreground form an arch leading into the rear third of the 4oft. and by virtue of the picture frame so formed create an illusion of distance. These trees with a great deal of sunlight, well fertilized each year and frequently sprayed, thrive and blossom in a way that would be creditable in their native soil. To afford a place for children to play, the entire fore part of the garden is paved with flag, leaving on each side a border only r8in. wide for planting. Such a small space may seem a poor playground to country boys and girls, but most city children have only streets or distant parks. The figure ("Baigneuse," by Roy Sheldon) in this garden is its most prominent feature and illus trates the value of good ornament in scale. A commonplace piece of sculpture may nestle into a thicket of greenery and appear delightful in a country garden, but only the really distinguished appears worth while at close range and against an unflattering background.

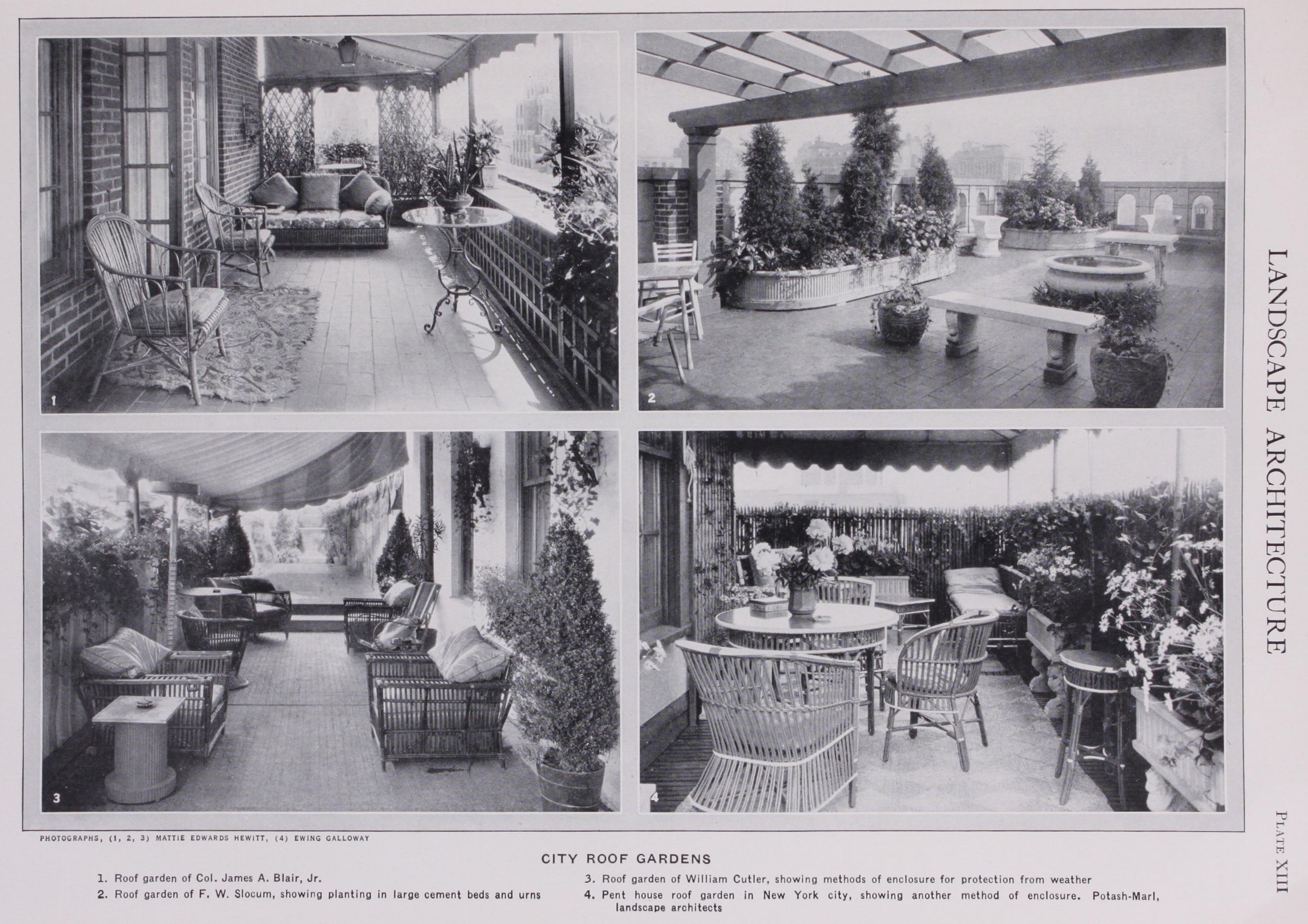

The considerations that determine the design of a city garden are even more potent when the area in question is on a roof. The im portance of architectural decoration increases as the possibility of successful vegetation decreases, and on the city roof the designer of the garden faces all the difficulties of the back yard with the added handicaps of wind and a scarcity of soil. Yet in the larger cities and especially in New York, penthouses on the roofs of the tall buildings are the pleasantest places to live in, and since each of these penthouses has a sort of piazza or front yard of tile roof in front of or around it, the roof garden has been the subject of many enthusiastic designs. All earth needed on the roof has to be transported; therefore it is usually wisest to arrange the planting in tubs and boxes. Under the most favourable circumstances no great depth of earth is possible; consequently the planting is limited to those things that will grow in shallow soil. Privet and English ivy are the chief resources; annuals such as calendulas, petunias, marigolds and morning glories will thrive; most evergreens die and have to be replaced at least annually; everything needs to be fertilized frequently in order to replenish the easily exhausted soil. Perhaps the best way to consider the roof garden is as a bit of stage scenery with an architectural background against which a few plants may grow well. The importance of the architectural background is at once apparent. If the constant expenditure of money for upkeep is possible, however, a standing order for potted plants can make any roof garden enchanting, for there is something irresistible in being high above the world and in a garden filled with bloom. Such roof gardens are illustrated herewith and show very well the importance of the architectural background and the effect to be obtained from plants in tubs and boxes. In all small gar dens, suburban, city or roof, the points to be emphasized are proper scale, a logical relation between house and garden, economy of plant material and good design in architectural accessories.

(R. DE.)