Lichens

hyphae, lichen, thallus, growth, alga, algae, filaments, cortex, gonidia and surface

Lichen Algae.

The algal constituents of the thallus belong to two classes. I. Myxophyceae (blue-green algae) and II. Chloro phyceae (bright-green algae). They are, in general, aerial forms and in a free condition inhabit moist shady situations. Though the determination of algal species is somewhat uncertain, the genus can be more easily recognized.

I. IVIyxophyceae associated with Phycolichens in Collemaceae and other families. The algae of most frequent occurrence are Gloeocapsa, Nostoc, Scytonema and Stigonema.

II. Chlorophyceae associated with Archilichens. Those of most importance are the globose algae belonging to the Protococcaceae and Trentepohlia, a filamentous alga.

The alga may become modified in the gonidial state : Gloeocapsa loses colour, Nostoc chains, and Trentepohlia filaments may be broken up into cell units.

Lichen Hyphae.

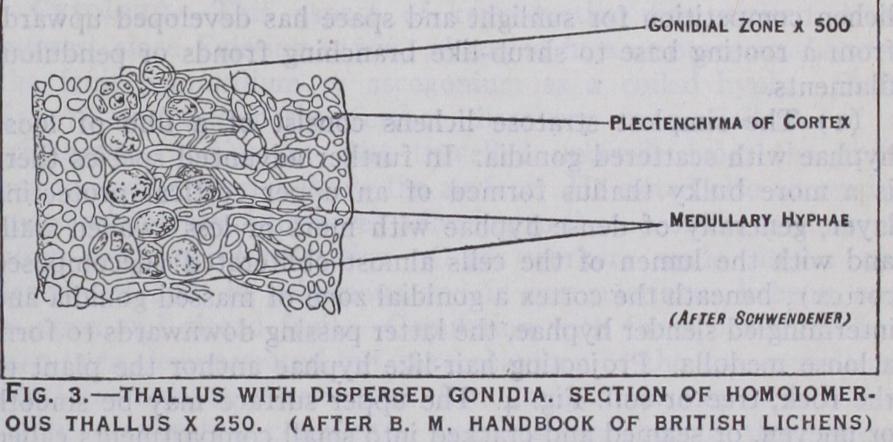

These undergo considerable modification as lichen symbionts. The fruiting form indicates their origin as ascomycetous or basidiomycetous, and their affinity can be traced to ancestral groups of fungi. Bonnier (1889) in describing their development from the spores in synthetic cultures noted three distinct types :—(1) clasping filaments with repeated branching which surround and secure the alga ; (2) filaments with short swollen cells destined to form several lichen tissues and (3) towards the periphery, searching filaments that form the hypo thallus and annex new algae. In five days after germination the clasping hyphae had laid hold of the alga and symbiotic growth had begun. In the growing regions the hyphae remain compar atively thin-walled. In other parts—especially in the cortex, etc. —the walls frequently become thick and gelatinized. In lichens as in fungi there is no true cell structure or parenchyma, but in the cortices of many lichens a pseudo-parenchyma or plectench yma arises by the closely packed growth of the septate tips of the hyphae. Plectenchyma also occasionally appears in other parts of the thallus.

Cultures in artificial media apart from gonidia have been made by several workers: by Moller (1887) with Lecanora subfusca; by F. Tobler (1909) and by Killian (1925) with Xanthoria par ietina. Also by Killian and Werner (1924) with the spores of Cladonia squamosa. In all cases the results were fairly similar : growth was slow and finally ceased—in Xanthoria parietina in eight or ten months. A series of tissues was however observed in the last culture : (I) a dense layer of filaments representing the medulla; above that (2) a looser tissue in the position of the gonidial layer; and (3) a second dense tissue representing the cortex from which arose aerial hyphae. Tobler further records that growth became more lichenoid when the gonidial alga was introduced and the yellow acid parietin appeared in the tissues. Werner (1927) tested hyphal growth on various media and found that galactose was the most advantageous food supply. Organic nitrogen was added as peptone and asparagin, inorganic as nitrate of ammonium. Growth was slow, but the addition of gonidia to the culture retarded it yet more, so that the algae gained in numbers.

The main interest in morphology lies in tracing the effect of symbiosis on development. The fungus as the dominant partner provides the structure of the thallus but the variety of forms evolved is due to the necessity of securing light and air to enable the alga to carry on the work of photosynthesis.

' General Structure of Ascolichens.

In these there are two main types of thallus:—(i) the stratose which includes flat spreading plants, crustaceous or foliose, in which the upper sur face alone is exposed to light ; and (2) the radiate which in the lichen competition for sunlight and space has developed upwards from a rooting base to shrub-like branching fronds or pendulous filaments.

(I) The simplest stratose lichens consist of a film of loose hyphae with scattered gonidia. In further advanced species there is a more bulky thallus formed of an upper cortical protecting layer, generally of dense hyphae with more or less swollen walls and with the lumen of the cells almost obliterated (decomposed cortex) ; beneath the cortex a gonidial zone of massed gonidia and intermingled slender hyphae, the latter passing downwards to form a loose medulla. Projecting hair-like hyphae anchor the plant to the rock, tree or soil. Fig. 4. The upper surface may be smooth or uneven, or seamed and cracked into small compartments called areolae. Not infrequently the crustaceous thallus is wholly em bedded in the substratum as in Graphidaceae. Such lichens on trees are termed hypophloeodal in contrast to the surface or epiphloeodal forms, a stain on the bark usually indicating their presence ; the fructifications are formed on the surface. Similarly rock lichens are epilithic or endolithic. The latter live in lime stone, which they penetrate to various depths. Friedrich (1906) noted in an im mersed species, Biatorella simplex, a slight cortical layer, below that a zone of gonidia 600-700 p, in thickness, while the medullary hyphae reached a depth of a 2MM. An in stance has been recorded of a lichen pene trating to 3omm. below the surface. Still higher in development are the squamulose thalli of tiny leaflets and the larger foliose (fig. 5) forms in both of which the thallus is raised from the substratum partly or en tirely and in which the free under-surface also acquires a protecting cortex which generally repeats that of the upper-surface—either of decomposed cells, of plectenchyma, or of hyphae parallel with the surface (fibrous cortex). Stratose lichens start from a centre, the growing tissue is situated in the gonidial zone and the greatest increase is at the periphery, the lichen gradually enlarging on all sides, in some to a size of one foot or more in diameter. Growth is continuous, but divisions may arise that are imbricate and leaf like. In squamulose forms the squamules arise in succession from the spreading hypothallus—the travelling ground hyphae. Foliose forms are attached at irregular intervals by rhizinae.