Light

theory, polarized, reflected, wave, elastic, discovery, medium, optical and formulae

The investigation of polarization at this epoch received a great impetus by the discovery of Malus that, when sunlight is reflected from glass, the reflected ray may be polarized. Brewster studied the matter and found the rule that the reflected light was com pletely polarized when the reflected and refracted rays were per pendicular to one another. In the course of this work he discov ered experimentally the formulae for the intensity of the two polarized components of light reflected from a transparent sub stance . If i is the angle of incidence and r that of refraction, the fraction reflected is or according to the direction of polarization. These expressions are usually called Fresnel's sine and tangent formulae, and have played a part in the history of optics. In the special case where i+r----9o° the tangent formula vanishes and, as the other does not, the re flected light is completely polarized. Brewster also made the important discovery that some crystals exhibit double refraction of a different type from that of Huygens. In these crystals there are two directions instead of only one for which the light does not become polarized. We may also here mention the discovery by Arago of gyration (formerly called "optical activity"). When a beam of polarized light is sent through a quartz crystal along the axis, or through a sugar solution, it is observed that, on emergence of the beam, the plane of polarization has rotated by an amount proportional to the length of the path it has traversed. We shall discuss all these matters in detail later.

The greatest investigator of this period was Fresnel, and in his hands optical theory attained the outline which it has kept ever since. As we shall have to deal with his work in detail we shall here only mention his discoveries without explaining them.

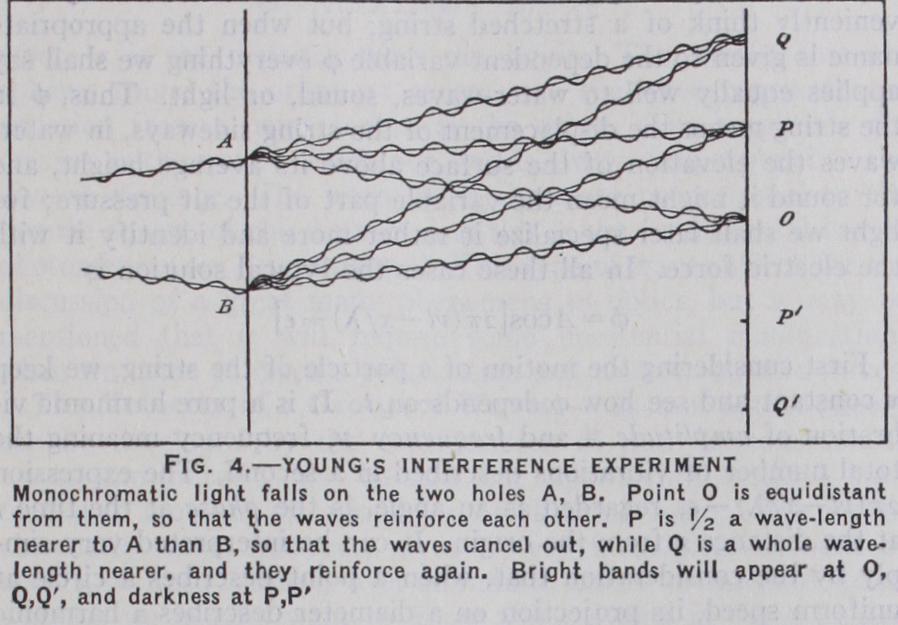

First he adapted Huygens' construction to explain diffraction, and thereby established the superiority of the wave theory over the corpuscular. In the course of this work he demonstrated the remarkable fact that there is a bright spot exactly in the centre of the shadow of a circular screen. Like Young he also made various experiments to exhibit the interference of two beams of light. He then turned his attention to the optical effects of moving bodies (including the motion of the earth) and cor rectly formulated all the principles ; this important work had a great influence in connection with relativity theory, but is out side our scope here. Next he made the discovery (with Arago) that, when two beams of light are differently polarized, even if they arise from the same source, it is impossible to make them interfere. At this period the vibrations of light were thought to resemble those of sound, so that there seemed to be no room for polarization in the theory, but Young hit on the solution that the vibrations were transverse, so that a wave of light may have sides, as Newton had said. Fresnel next turned his attention to

double refraction and completely solved the whole• problem, uniting into a single system both Huygens' uniaxial and Brewster's biaxial types. Finally he deduced theoretically the laws of re fraction and reflection, and obtained the sine and tangent formulae to which we have referred. Fresnel's whole work was devoted to establishing rigorous principles for light, and the enormous progress he made is the more remarkable when we remember that the mathematical theory of waves was only in its infancy, and that there hardly existed at all any dynamical theory of continuous media.

The Dynamical Theories of the 19th Century.

With the discoveries of Fresnel, the more geometrical part of the wave theory of light was practically complete ; but it was still necessary to build a proper dynamical formulation, and this was the chief preoccupation of theorists during most of the 19th century. It was felt necessary to make a model of some sort of matter which should behave like the optical medium. The most obvious model suggested was that of an elastic solid, and, with the help of this, Cauchy, Neumann and others had considerable success in ex plaining the phenomena for a single medium, but the theories got into difficulty when it came to the passage of light from one medium to another. Only by highly artificial hypotheses was it possible to obtain the sine and tangent formulae.

The work of Green on the propagation of waves in elastic solids is the real beginning of the modern mathematical theory of waves. A piece of solid matter can be strained (altered in form or position) in three ways. It may be compressed without other change of form, or it may be sheared so that a square becomes a rhombus, or, without changing its shape, it may be rotated in position. The third type of strain can take place without the necessity of forces, but the first two require the action of forces in order that they may occur. The solid will possess two elastic constants corresponding to these forces (we are thinking of an isotropic body, not a crystal which may possess 21), and can propagate two types of wave, a longitudinal corresponding to compression, and a transverse corresponding to shear. Green showed that when a transverse elastic wave passed from one medium to another it could not help giving rise to a longitudinal wave, and for this there is no room in the theory of light. Though his result was thus mainly negative, Green's calculus firmly established what conditions a valid theory must satisfy. Under the inspiration of Green's methods Stokes gave a rigorous solu tion of the problem of diffraction in place of Fresnel's approxi mate geometrical method.