Lithography

printing, stone, press, sheet, paper, artists, artist, art and marks

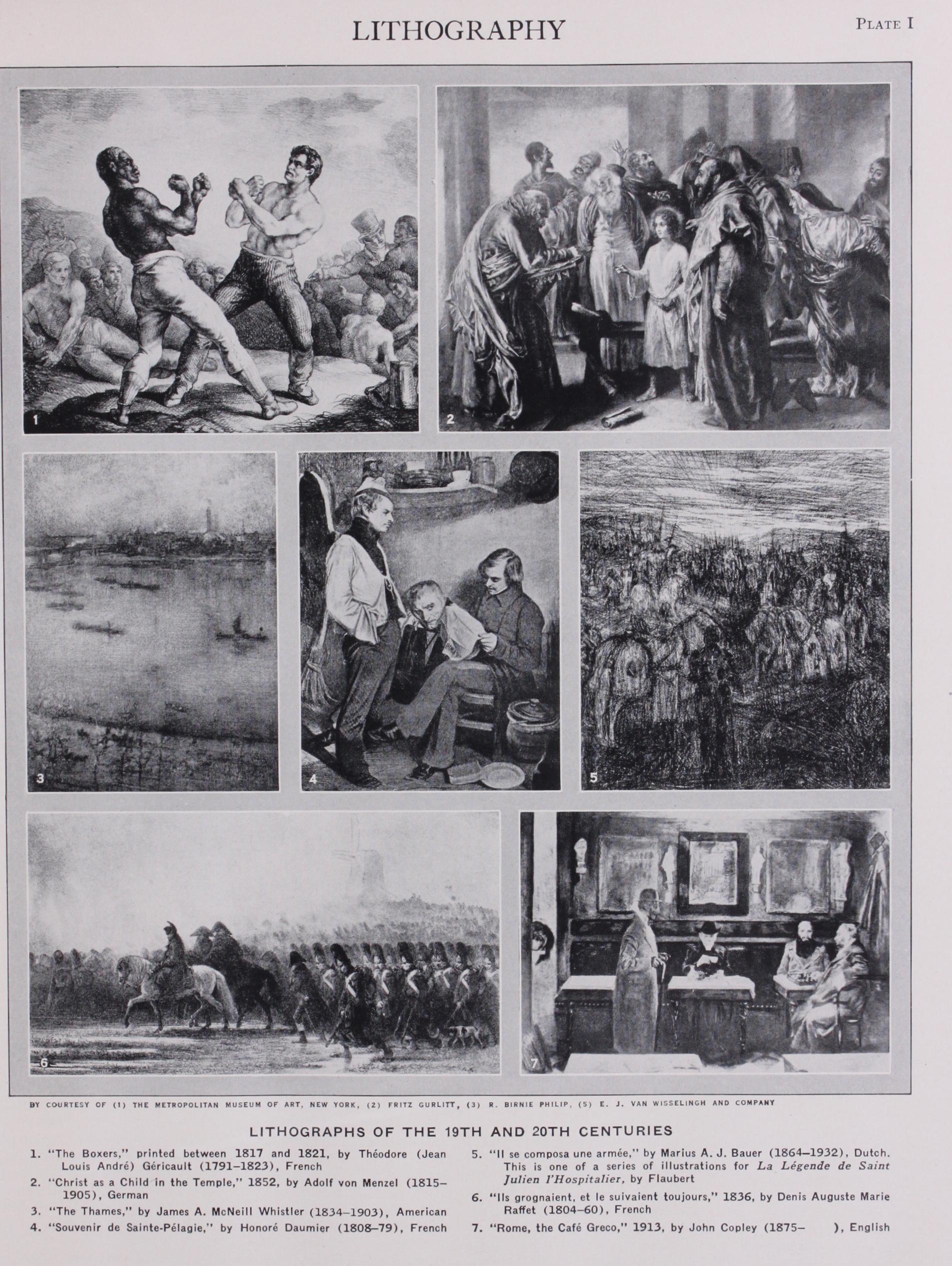

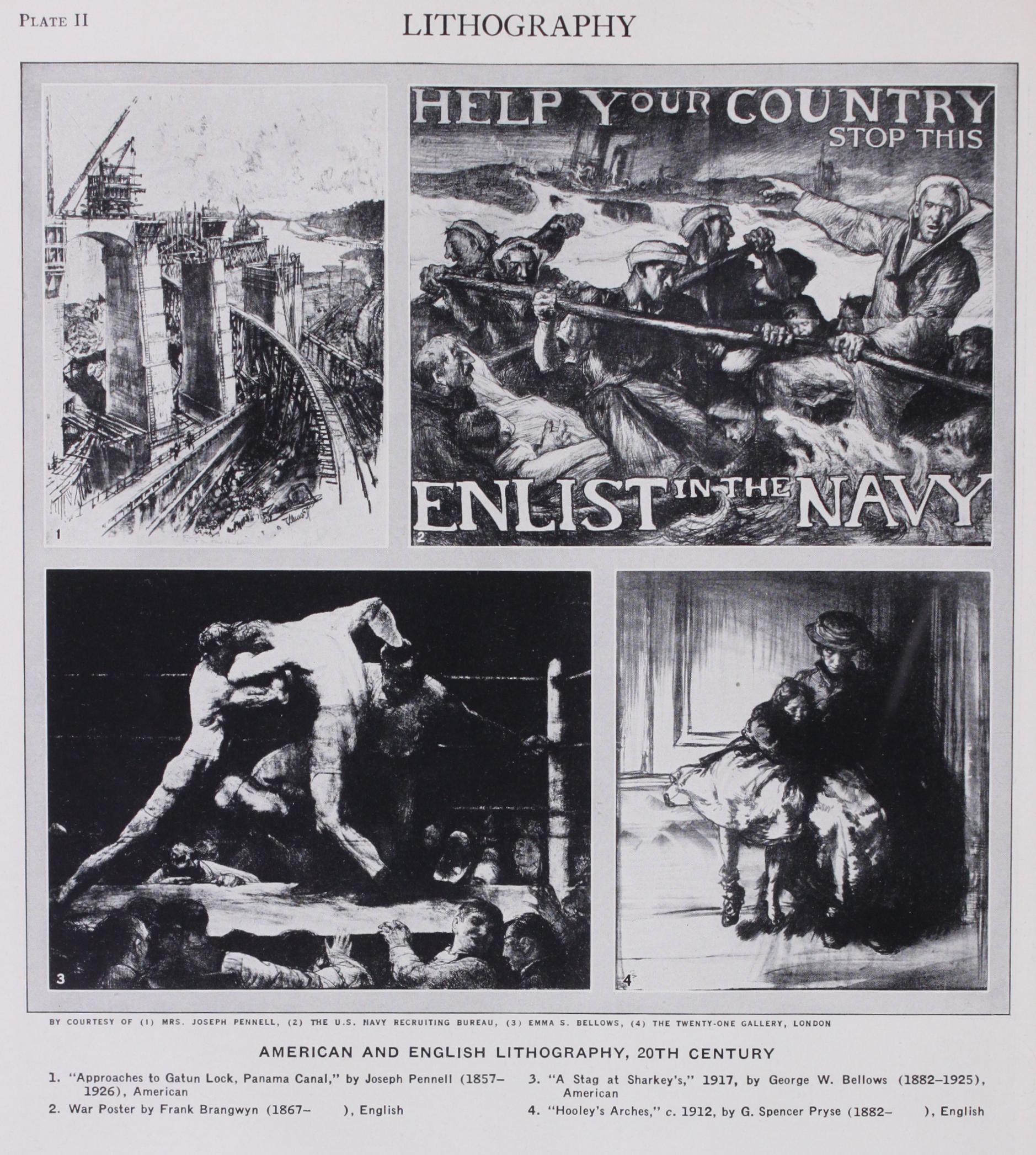

Diisseldorf chose the same year for its Centenary Exhibition as Paris (1895-96), and German and Austrian artists played their part in the revival. Hans Thoma and Max Liebermann, Greiner, Unger and Fischer, one woman of power and distinction, Kathe Kollwitz, had revived the traditions of the great days in Ger many. A few lithographs were published during its short life by the magazine Pan and excellent work has been done at the Pan Printing Press in Berlin. Jugend opened its pages to the men of the younger generation, reproducing their lithographs. And a number of other magazines and papers have, with more or less success, looked to lithography for their principal attraction. Bel gium has contributed to the chronicles of lithography, and Felicien Rops, Henri de Groux, Emil Claus, Fernand Knopf are among the masters. In Holland, Bauer, Von Hoytema, Van Toroop, Van s'Gravesande, Jacob Maris, Veth, are names to be remembered. In New York the Grolier Club arranged an Ex hibition in 1896 which probably was an influence in awakening American artists, so long lukewarm. Arthur B. Davies, experi menting in colour, Albert Sterner, George Bellows, Charles Locke, a much younger man, are the most prominent of the too small group of artists who have as yet practised the art in America. J. McLure Hamilton also is an American, but his work has been done mostly in England. Factors in arousing this new interest were the improvement of transfer paper, the use of aluminium plates, the growing tendency of the artist to print his lithographs himself on his own press.

Since 1900 lithography has been more alive and active in England than elsewhere. Public interest dwindled after the Vic toria and Albert Museum Exhibition but not the interest of artists.

Certain magazines even in the '9os opened their pages to lithog raphers, whose work may be found in The Pageant, The Savoy, The Studio, The Magazine of Art, The Art Journal. But 19o7–o8 brought the boldest venture of all, The Neolith, a quarterly which lithographed text and illustrations alike. It ran for only four numbers. But almost immediately three men associated with it, A. S. Hartrick, F. Ernest Jackson, J. Kerr Lawson, to whose number Joseph Pennell, who had been living in England for years, was promptly added, established the Senefelder Press, which was soon abandoned, and organized the still prosperous Senefelder Club with Pennell as president. The first exhibition was given in the early winter of 1909 and since then annual exhibitions have been held in London and many others throughout Europe and America. Most of the distinguished lithographers of the day became members: J. McLure Hamilton, C. H. Shannon, John Copley its first secretary, E. J. Sullivan, Ethel Gabain, Spencer Pryse, Frank Brangwyn, the second president. The club already in the first quarter of the century did much to restore lithog raphy to its rightful place among the graphic arts, and upon it the future of the art, in a large measure, now rests.

Lithographic Printing.

The work of the lithographic printer commences at the point where the lithographic artist com pletes the drawing. When a stone with a design drawn upon it is sent to the press, the printer has a delicate task to perform in order to prepare the work for printing. It has to be etched with a weak acid, covered with gum arabic, and rolled up with printing ink, and during this work extreme care has to be taken that the delicate lines in the drawing are not destroyed. A proof is then pulled on the press and submitted to the artist, who may find it necessary to add further work or to delete some of the work he has already put on to the stone. When the artist is satisfied, finished proofs are pulled and submitted to the customer. When it is a colour job, cross-lines called "register marks" are included on the margins of the "key" and printed on the sheet of paper, each printing having to register to these marks. When printing on the press, needles are put through the marks on the paper, and registered to similar marks on the stone. When printing on the machine the sheet of paper is "fed to lays," and great care has to be exercised to place the sheet accurately into the "lays" each time it passes through the machine.

When the work is finally passed, transfers on special paper are pulled in a greasy ink upon the hand-press from the original stone. These are patched up and fixed on to a sheet of the paper on which the job is to be printed, this having previously been ruled to the size required. The sheet of transfers is then placed face downwards on to a stone or plate and run through the press until the design adheres to the printing surface. This is followed by a series of operations of gumming, rolling up, cleaning and etching. It is by printing a number of designs together on one sheet that large editions can be economically produced. After printing, the prints are cut up singly.

In a large measure, thin sheets of zinc and aluminium have taken the place of stones during the last quarter of a century, but the same principles of preparation apply, with the distinction that a different etch may be used for the various surfaces. It is doubtful, however, if an equivalent quality of work can be ob tained from a plate as from a stone. The call of the age for a speedier method of production made plates necessary. The prin cipal advantages of plates are that they do not occupy the same space as a stone when storing and that they can be fixed round the cylinder of a rotary machine, which produces at least three times as many impressions in a given time as those used for stone printing.