The Atomic Theory of Refraction

light, atom, magnetic, polarized, gyration, constant, rotation, virtual, plane and direction

Each molecule emits a screw-wave which has axis along x. In any direction a screw-wave can be resolved into a main com ponent which is like that of a line-wave and a weaker component at right-angles and a quarter period behind. Take p for the scattering constant of the line-wave and for the other com ponent. Then, when we sum all the waves scattered by the mole cules, the line-waves will compound as before into and this means that the light is now plane polarized at angle ó2rNal ē 2771X to the x direction. The rotation is proportional to 1, the thickness of the sheet, and the other factors express the gyrational constant. The theory for matter in bulk gives a similar result, but presents it by showing that there are different refractive indices for right- and left-handed circularly polarized light.

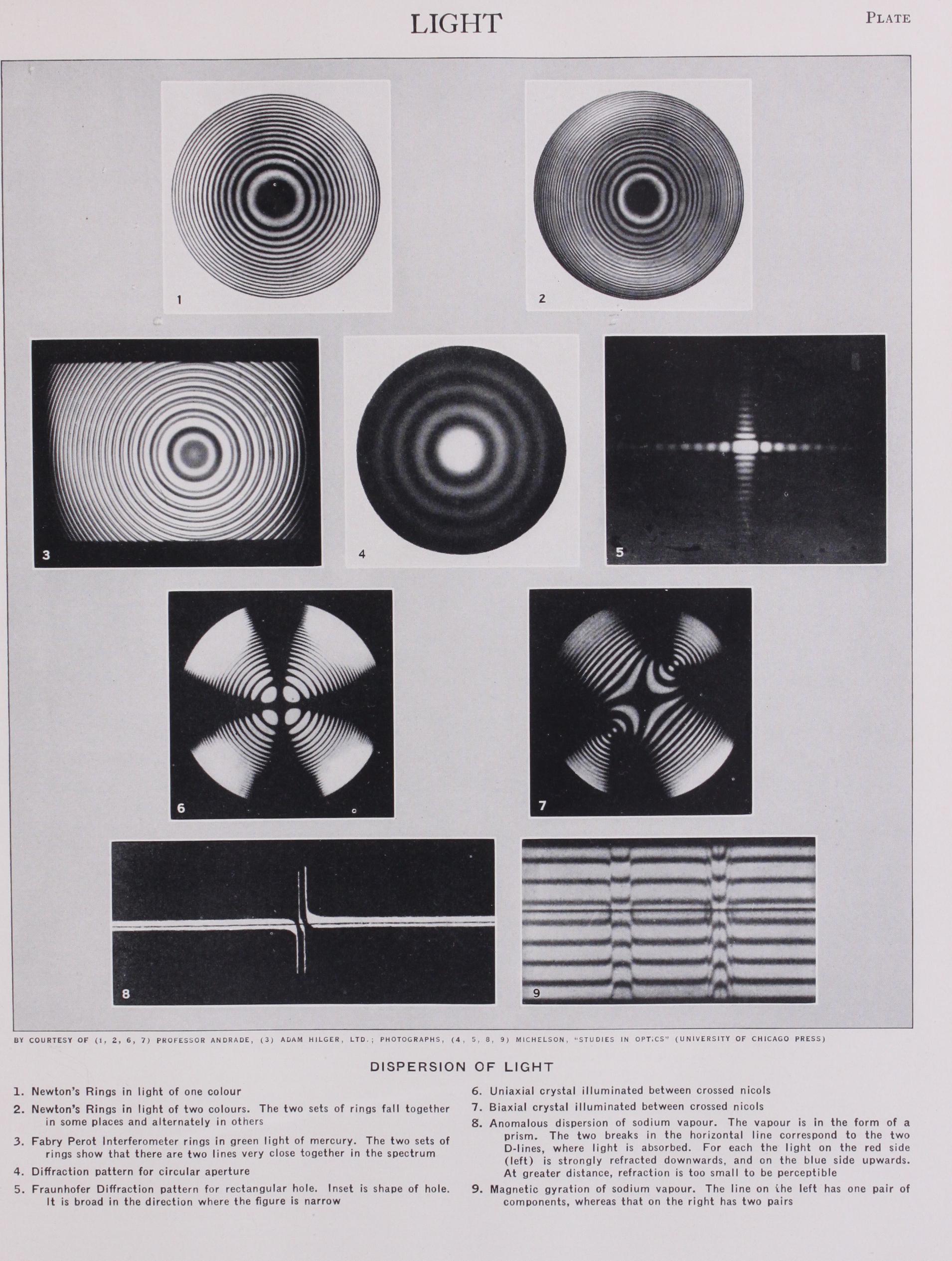

Magnetic Gyration.

In our discussion of the refraction of isotropic bodies, we saw that plane polarized light might be sup posed to stimulate the emission by the atom of a line-wave. Now circularly polarized light can be constructed out of two plane polarized components at right angles and differing by a quarter wave-length in phase, and what we have called a circle-wave can be constructed out of two line-waves with perpendicular poles and phases differing by a quarter period. Consequently we could have worked out the theory of refraction just as well using circu larly polarized light and circle-waves, and in discussing magnetic gyration it makes a convenient starting point to do so. When an atom is in the presence of a magnetic field it behaves in a sense as though it were in rotation, about an axis along the field's direction, with velocity proportional to the field strength. We shall see how this comes about when we discuss dispersion, but can explain the gyration without reference to the detailed theory. If then the atom is illuminated by circularly polarized light, it will react differently according as its magnetic rotation is with or against the rotation of the light-vector. We may describe what happens by saying that the atom's scattering constant will no longer be p, but and pór for the two types of circularly polarized light. Here r will be proportional to the strength of the field, and it is usually to be regarded as much smaller than p.

Suppose that the incident light is 271- 2 7 (ctóz), Ey= (ctóz).

When the scattered wave from a thin sheet is superposed on this, we have, by the same construction as before, Ez=Fcos--Ir Ey=Fsin-Z [c1óz+ 2 But if the incident light is of the opposite type it will be 2r 2r EĄ= (ctóz); and the resultant wave will be COS- 271 [a- Z-F 271-N r)1], X Ey= - 2 If we add these two solutions together the incident light is so that the plane of polarization has turned through an angle (27r-Nrl). This is proportional to the thickness of the sheetand, through T, to the strength of the magnetic field. The re maining factors are individual to the substance of which the sheet is made. The constant is often called the Verdet constant after one of the earlier investigators who measured it for a number of substances.

The magnetic gyration is usually very small for practicable magnetic fields. It occurs in all transparent isotropic substances and for light going along the axis of uniaxial doubly refracting crystals; for other directions it is masked by the double refraction.

There is a very remarkable similar effect, when polarized light is reflected from the polished pole of a magnet. For perpendicular incidence the plane of polarization rotates, and for other directions there are similar more complicated changes in the rule of reflec tion. The Kerr effect, as it is called from its discoverer, is evi dently like the magnetic gyration in transparent substances, but its theory is very incomplete.

The two types of gyration, natural and magnetic, are radically different in character, as is shown by the fact that one depends on a screw-wave, the other on a circle-wave. The consequence is that in natural gyration, if the light is reflected back so as to traverse the sheet again, its direction of polarization turns in each passage like a screw of the same type and so it comes back to its original polarization. On the other hand magnetic gyration is due to a rotation, not a screw, so that if the light is reflected back again it rotates in the same direction as before and the angle of turning is doubled.

We have traced the optical effects of matter in bulk to their source in the atoms, and in doing so have only found it necessary to use the ordinary conceptions of the classical theory of dynamics, but as soon as we begin to consider the atoms themselves we get into difficulties, because in fact the atom obeys quite different dynamical rules. These rules, which are the principal subject of the quantum theory (q.v.), are fairly well understood, but since our whole practical experience is based on classical dynamics, they are very hard to apprehend in anything but mathematical form ; regarded physically they appear to contain an unsatisfying element of irrationality, which is really to be attributed to limita tions in our habits of thought. For the purposes of the present subject it is fortunately possible to some extent to avoid these difficulties. The quantum theory gives certain rules, very unlike those of ordinary dynamics, for the intensities and frequencies of the spectral lines emitted by an atom or molecule, and it also predicts how such an atom will behave under the influence of light. Though both these aspects of the theory are quite different from ordinary dynamics, they have this in common with the classical theory, that if we make up a purely classical model to imitate the emission (though in many other properties it will be quite wrong), it will react correctly for the scattering of light. For convenience of calculation we thus imagine that associated with each atom is a phantom virtual atom, which will suffice to work out the optical effects. An actual atom contains only a few electrons, but the virtual atom contains a virtual electron for each line of its spectrum, and the charges on the virtual electrons are usually much smaller than the known charge of an electron. Since the spectrum is composed of nearly monochromatic lines, we suppose that each virtual electron is free to execute approximately harmonic vibrations. The relation between the emission and the scattering of light by the atom is then akin to the relation of free to forced vibrations in a harmonic vibrator.