Thermometry

liquid, pressure, temperature, vapour, mixture, boiling, curves, composition, curve and mixtures

Absolute Zero Unrealizable.

Since the value of L varies with temperature, becoming zero at the critical temperature when V =v, one can only apply the last equation with such limits of temperature as allow one to assume that its value is constant. In order to arrive at an equation of a general character it would be necessary to know the value of L. at the absolute zero, and the constants in some equation such as As this is impossible, it follows that thermodynamics does not enable us to arrive at an absolute relationship between tempera ture and vapour pressure. It has already been pointed out that the kinetic theory fails equally in this respect. However, as has already been pointed out, the law of corresponding states (q.v.) may be applied to the calculation of the temperatures at which two gases have the same vapour pressure, and this method was used to calculate the temperatures below I° absolute, obtained by evaporating liquid helium in vacuo. Also researches at low temperatures, particularly by Nernst, have resulted in the develop ment of formulae connecting vapour pressure and temperature based upon the Clausius-Clapeyron equation, which, though semi empirical, are of great practical value. Both from the standpoint of the kinetic theory and of thermodynamics the absolute zero must be regarded rather as a mathematical conception than as a physical reality, and entirely unrealizable.

Mixtures of Gases.

The separation and purification of gase ous mixtures by liquefaction and subsequent distillation is of use in industry and the laboratory. We will consider the subject generally. The vapour pressure of a pure substance depends upon the temperature only ; that of a mixture depends upon its tem perature and composition. Also the composition of the vapour in equilibrium with the liquid is not, except in the case of constant boiling liquids, identical with that of the liquid. The vapour pres sures of mixtures of two gases A and B at constant temperature t may be represented on the pres diagram (fig. 2o) by curves which terminate in points and Pb, the vapour pressures of the pure substances. The abscissae refer to the com position of the liquid, the pres sure being measured at the mo ment at which the same weight, or molar equivalent, of gas is just completely condensed. In the case of most mixtures the curve has the form b, and lies wholly between horizontals through and Pb. If any quanti ty of such a liquid in equilibrium at pressure p is taken, and it is al lowed to evaporate partially, the pressure will fall, and the liquid will become continually poorer in the more volatile constituent. It is possible to separate the constituents of such a mixture by the process of condensation and evaporation. When the equilibrium curve shows a maximum or a minimum, as in cases a and c, if the liquid is allowed to evapo rate at temperature t, the composition will change as evapora tion proceeds but with rise or fall of pressure, till the composition corresponding to the maximum, or minimum point, is reached when the remainder of the liquid will evaporate completely at con stant pressure, without change in composition, which is that of the constant boiling mixture at pressure p. However, if we obtain a series of pressure-concen tration curves for t, t', t", etc., we find that the position of the maximum or minimum changes, (fig. 21) and that if a pair of gases form a constant boiling mixture under one set of condi tions, they may be separated by submitting such a mixture to evaporation under different con ditions of temperature and pres sure.

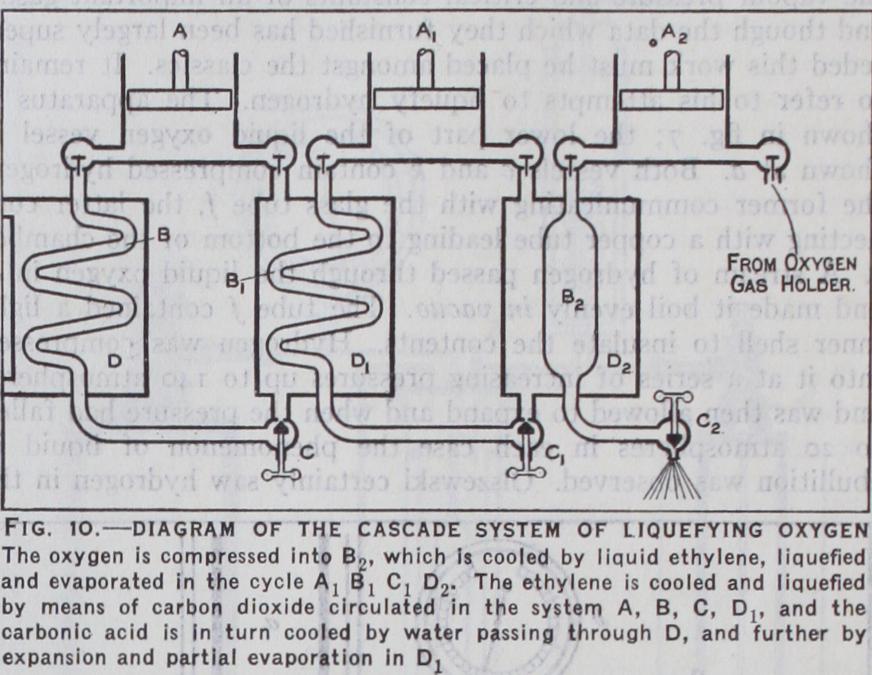

The relative properties of mix tures and simple substances is very well illustrated by the ac companying pressure-temperature diagram (fig. 22). Here the sim ple curves on the extreme right and left are the vapour pressure curves for simple gases B and A, actualy sulphur dioxide and car bon dioxide and the loop-like curves 3, 2, and I represent the pressure temperature relations of mixtures containing 25, 5o and 75% of A respectively. If now we consider mixture 2 at temperature 9o° C, if the pressure was raised to 5o atmospheres, corresponding to a point a' on the diagram, liquid would first appear. At 6o° C liquid would first appear at 24 atmospheres, and at the highest temperature at which the mixture could be liquefied, about io°, which is not the critical point, the pressure would be about 90 atmospheres. The curve which is the locus of these points is called the dew-curve. Now if at either of the two lower temperatures the pressure is increased the quantity of liquid also increases till the whole is liquefied, and the locus of the points b b' at which this happens forms the upper part of the loop, which is called the boiling curve. At b" and between this point and the vertical through C2 a curious thing happens. As the pressure increases liquid will appear and then disappear. However, the two curves, speaking only of the particular mixture which we are considering, repre sent temperature-pressure conditions under which both liquid and vapour can exist. Any point outside the loop and to the left of relates only to liquid, and any point outside the curve below and to the right of the loop relates to vapour only. A number of similar loops can be used to represent p.-t. relationships for all possible mixtures of A and B. Three only are drawn, and they will be seen to intersect. At d the dew-curve cuts the boiling curve and this means that at 105° and 7o atmospheres a vapour containing 5o% of A is in equilibrium with a liquid con taining 25% of A, A being the most volatile constituent. One would expect this to happen except in the case of a constant boiling mixture when the dew-curve and the boiling curve touch at a point. Now if one imagines a very large number of such inter lacing curves to be drawn it is obvious that they would tend to intersect along the line C2 Cb. That is dew-curves and boiling curves of practically identical composition would in tersect at points representing identical temperature and pres sure conditions. At these points the composition and density of the liquid and vapour would be identical, and these are the critical points of the mix tures, and not points such as d", which represent the highest temperatures at which the mix ture can be liquefied.