Strength of Timbers

load, beam, weight, breaking, factor, carry, supported and safe

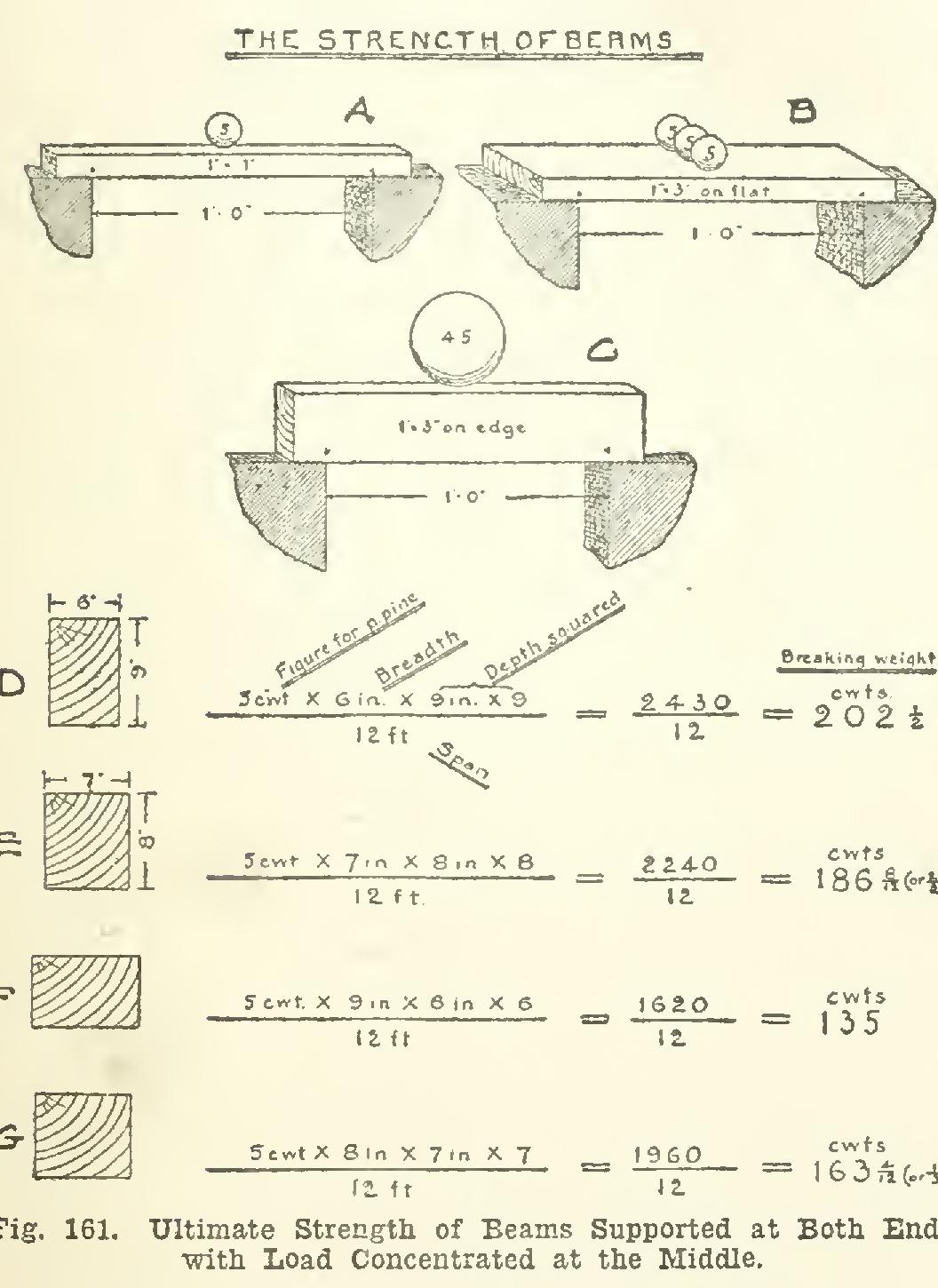

But suppose the same beams had been laid flat instead of on edge, how would they work out then? F and G give the results, which show that the 8 by 7 beam is a good deal stronger than the 9 by 6 if used in this position.

It must be observed, of course, that these are the breaking weights for beams, and it is ob vious that the safe load is what is warted. This is found by dividing the breaking weight by a certain factor (known as the factor of safety)— generally 4 or 5 for a dead load, and 8 or 10 for a live load.

It must also be remembered that the forego ing formula is for a beam loaded in the center. If the load is distributed evenly throughout the length of the beam, it will carry just double what it would if loaded in the center.

To sum up the matter, the points to carry in one's head are these: First, the figure given in the table for the particular wood. Second, the way of putting down the simple sum or formula, which must be as shown in Fig. 162. Third, divide your result by figure (factor) of safety, say five for dead load and ten for live load. (This gives safe load for center of beam. If load is distributed, multiply this by two.) Thus divested of all formal language, this useful little working formula was easily grasped by my two interrogators; and, in the hope that it may prove similarly useful to many others, the writer begs to present it.

Strength of Beams Supported at One End. "More work for the calculator," was the remark which greeted the writer the other day, as his two carpenter friends once more came into the office. "We have been applying your last little lesson on the strength of beams to several cases which have occurred in our work lately, and have found no difficulty in arriving at correct results. In fact, we have been 'showing off' a little amongst our mates, in consequence," con tinued the spokesman. "But we are up against another little problem now, and shall be glad of another lesson if you can give us half an hour or so." Proud of his apt pupils and their evident ap preciation of his efforts, the writer was only too pleased to put his services again at their dis posal, and, after a brief talk, found the problem to be as follows: A wooden beam was to be fixed so as to pro ject some five feet from the face of a building, for the purpose of hoisting goods from the street level to a. warehouse on the upper floor. (The technical term for a beam in this position is cantilever, and such a beam will be referred to by that name throughout this discussion.) A

piece of pitch pine 7 inches by 5 inches had been selected for the job, and the question arose as to the amount of weight which could safely be hoisted upon it.

First of all, we ran over our last lesson on the strength of a beam when supported at both ends, and found out what load a piece of pitch pine, 7 inches by 5 inches, and 5 feet long, would carry if placed on edge, when supported at both ends and carrying a central load. Our rule, or formula, used in the last lesson was of course required.

This gave us the result shown in Fig. 163, at 245 cwt. as the breaking weight re quired. It will be remembered that in the previous article it was stated that a beam with a distributed load will carry twice as much as the same beam with a central load, and that there fore the answer to this sum could be doubled for such conditions. But it is obvious that the strength of a beam supported at both ends is much greater than that of one supported (or fixed) at one end only, and is, relatively, as 4 is to 1.

Therefore, to find the breaking weight of our piece of 5 by 7 when fixed as a cantilever, we divided our result by 4, giving us cwts. But it was the amount our cantilever would carry which we wanted to find; and that brought in the question of the relation between the breaking weight and safe load—or, as it is termed, the factor of which reference was made before.

In this connection, the nature of the load or stress to which the beam is to be subjected is important, and may cause the safe load to vary from one-fifth to one-tenth of the breaking weight, according as the load is a live or dead one. Our load in this case was, of course, a live one; but another consideration entered into the question—namely, the manner of applying the hoisting force. That is to say, we had to con ider whether the force was to be applied in a series of jerks such as given by sailors in pull ing on a block and tackle, or to be steadily and continuously applied as by a winch or hoisting drum. If in the first manner, the greatest mar gin of safety would have to be allowed; and, at most, only one-tenth of the breaking weight should be carried. For the continuous, steady, pull, however, a factor of safety of one-eighth would probably be sufficient. As the power in this case was a drum driven by an electric motor, we decided upon eight as our factor, and applied it to our breaking weight ob taining approximately 7% cwts.