Dictionary of Masonry Terms

stone, stones, wall, mortar, headers and laid

Such defective work in placing stone can easily be detected by moving it slightly with the foot; if the stone touches another, the jar is dis tinctly felt. This specification refers principally to rubble work.

(5) No stone shall be dropped or slid over the wall, but shall be placed without jarring the stones already laid. After the mortar has par tially set, a jar may destroy the adhesion to the stone, and further setting will not entirely re pair the damage.

(6) No heavy hammering shall be allowed on the wall after a course has been laid. It is a custom with careless masons to get a stone in place, and then, with a heavy hammer, break off any projection beyond the face of the wall. This is objectionable for the reason given in (5).

(7) If a stone becomes loose after the mor tar has set, it shall be relaid with fresh mortar.

(8) Each stone shall be cleaned and damp ened before laying. The stone is moistened so that it shall not draw the water too rapidly from the mortar, and it is cleaned to promote adhesion of the mortar.

(9) Stones shall not be laid in freezing weather, unless by special permission. If this is allowed, the stones shall be freed from ice, snow, or frost by warming, and shall he laid in mortar made of heated sand and water, or, with proper precautions, mixed with brine in the proportion of one pound of salt to 18 gallons of water, when the temperature is at the freezing point. For each degree of temperature below freezing, an additional ounce of salt is used.

(10) Mortar to the depth of one inch shall be removed, before it has set, from the joints and beds from the exposed face of the wall. After the mortar in the wall has completely set, and the stone is free from frost, the joints shall be wet and filled with mortar made of one part Portland cement and three parts sand. This mortar shall be pounded in with a calking tool, and finished with a beading tool used with a straight-edge.

(11) First-class masonry shall consist of headers and stretchers alternating; at least one fourth of the wall shall consist of headers ex tending entirely through the wall. Every header

shall be immediately over a stretcher of the un derlying course. The stones of each course shall be so arranged as to form a proper bond with the stones of the underlying course. A bond of at least one foot will be required. In general, the stones should overlap the stones below an amount at least equal to the depth of the stone.

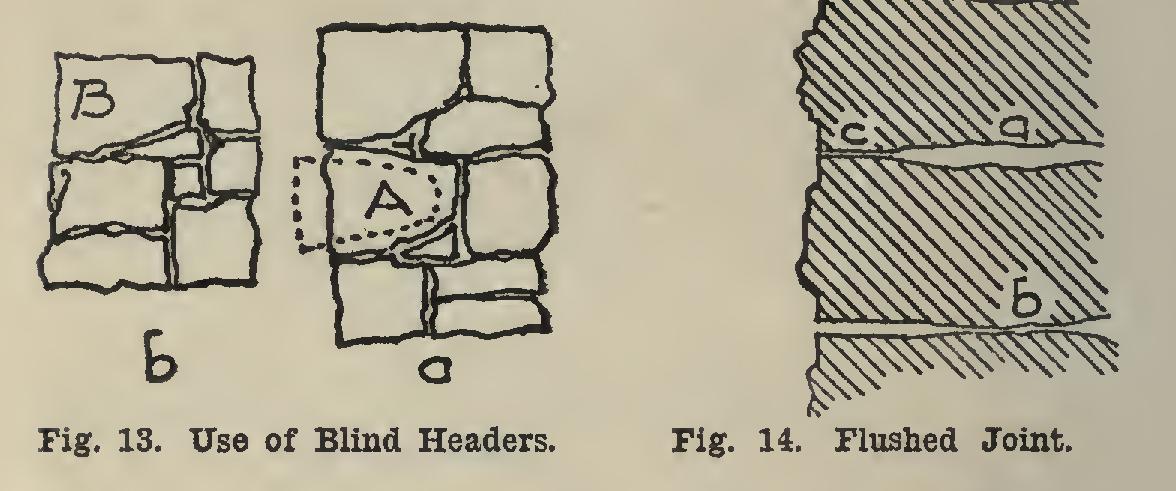

Blind headers

are stones of the proper di mensions on the face, but extending only a short distance into the wall. This practice is fre quently resorted to, and the inspector must be alert to prevent it. When the wall is over four feet thick, it is not specified that the headers shall extend through. In this event the header need go only to the stretcher on the opposite face.

It is sometimes specified that "headers shall hold the size in the heart of the wall that they show in the face." The sketch a in Fig. 13 shows the violation of this rule. The stone A is represented in elevation, and it is readily seen that pressure from above has a tendency to force it into the dotted position. Sketch b shows, in plan, a wedge-shaped stone B; and it is apparent that vertical pressure will not force it out of po sition if it be of uniform depth from front to end. For this reason it is often allowable to use stones of this shape in walls of not very high class masonry.

Stonecutters often cut away too much from the top and bottom of stones in order that the plane surface marked c, Fig. 14, may be more easily prepared. The practice is bad in first class work, and can be detected only during con struction or when the stone cracks on account of the concentration of pressure on too small an area. Such a joint is said to be flushed.

A practice even worse is shown at b in the same figure. Here not enough has been cut away and the pressure is again on a small area in tlie interior, and the joint is open.