General Principles of Reinforced Concrete Design

column, action, beam, bars, rods and square

The Trussed Steel Concrete Company pro duce in one of their publications a few interest ing phases of stresses in beams, and the action of reinforcing agents. Fig. 44 shows a beam re inforced with one of their products, in which it is claimed there is the action of a complete Pratt truss. The reinforcing bars should extend to the top surface of the beam for such an action.

Fig. 45 shows their conception of the truss action in a beam with horizontal reinforcement and stirrups. In each of these, the steel diag onals and stirrups form the tension web mem bers, while the compression web members are supplied by the concrete.

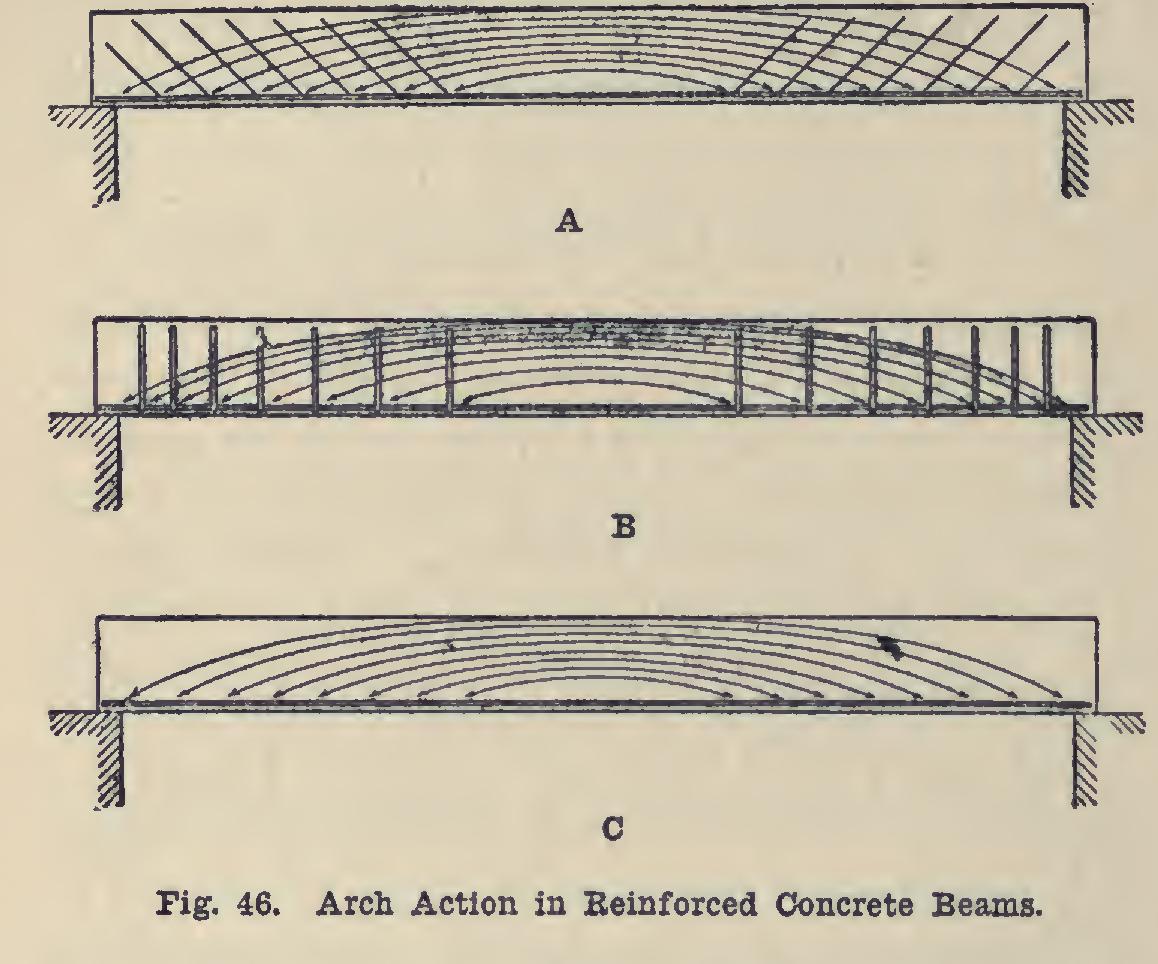

Fig. 46 shows the arch action in reinforced beams, A showing that of a beam reinforced with Kahn trussed bars; B, that of a beam with hori zontal reinforcement and stirrups; and C, that of a beam with horizontal reinforcement only.

The principles which govern the design of re inforced columns vary somewhat from those used in the design of beams and floors. Shear plays a prominent part in the failure of a con crete column. When a plain concrete column fails, the general tendency is one of bulging, and sliding of the concrete in the bulged part.

Longitudinal rods of small diameter, when placed near the surface and not connected, do very little to prevent this action, on account of the bending of the rods. Longitudinal rods tied or bound together by bent bars or heavy sheet fabric so as to form a stiff cage surrounding the core of the column, will prevent this buckling action. Many engineers prefer a round or square bar construction to the flat hoop form, on account of better bond in the concrete, es pecially if the space between the flat bars is small.

We have already referred to the possible tendency in the column to bend when subjected to eccentric loading. If the center of gravity of the applied load at the top of the column does not exactly coincide with the center line of the column, the compression increases on one side of the column and grows less on the other. The

limiting boundary within which the center of gravity of the applied load can act, and yet not put one side of the column into tension, is the middle third for a square-section column, and the middle fourth for a round-section column.

Besides the weakening effect of the tension in such a case of loading, the shear (another weakness in concrete) is increased on the com pression side of the column. When longitudinal bars bound together as just described are used, the flexural stresses and the tendency to bulge are resisted.

Godfrey suggests that a round or octagonal column with a coil of square steel rods the diameter of the column, the coil itself the diameter of the column, bound together by wir ing to the inside of the coil eight longitudinal rods of same size material as the coil, will pro duce good results. For lengths of columns up to ten diameters, 550 lbs. to the square inch is recommended as the allowable unit compression in the concrete. For lengths between ten and twenty-five diameters, he suggests that the in which 1 is the length of the column in inches and D is its diameter in inches, will give the allowable pressure per square inch in the sec tion. Twenty-five diameters should be the lim iting length of column.

In columns which carry heavy loads, as in high buildings, a more suitable construction is that of a steel framework, built up of channels or angles and lattice-work, which is then filled with and surrounded by concrete.