Cabinet

cable, cables, time, submarine, ocean, current, land and moved

There is no provision in the United States Constitution for a cabinet to advise the President, although in two places mention is made of the heads of departments. Washington at first turned to the Senate as a council to advise with him, but this plan proved impracticable. Then for a time he followed the practice of asking the advice in writing on specific questions of his secretaries of the treasury, state, and war, the attorney-general, chief justice, and Vice-President. On April 4, 1791, he wrote a letter to the secretaries of state, treasury, and war which brought about the first cabinet meeting in American history. But not until two years later did this precedent develop into frequent consul tations at a fixed place—usually the President's house. Jefferson, as secretary of state, first wrote of the President's council as "our cabinet" in 1793, and the term gradually became common from the English practice. But the word cabinet has never been introduced into the laws. President Harding in 1921 went back to the early practice of Washington by inviting Vice-President Coolidge to the cabinet meetings.

rIABLES,

SUBMARINE. If you would vi-it the bed of the At lantic between the United States and Europe, you would find a number of stout gutta-percha covered cables lying in the slimy ooze of the ocean floor, stretching from land to land.

These are the submarine electric cables over which the New World and the Old still send their telegraphic messages to each other, in spite of the growing use of "wireless." They are the wonderful cords that bind the modern nations into one great group, so that a business man in New York can send his order to London and get a reply, sometimes within the space of three minutes.

Similar cables connect us with South America, with Alaska, with the Philippine and Hawaiian islands and other islands of the Pacific, with Aus tralia,Japan, China, and India.

Every important seaport in the world is linked with this great cable system, so that the remotest points of civiliza tion are now in closer communication than were parts of the same country before the invention of the telegraph and telephone. In all there are enough miles of submarine cables to girdle the globe 13 times, and the cost of laying them amounted to over a quarter of a billion dollars.

Telegraphing under water is quite different from telegraphing on land.

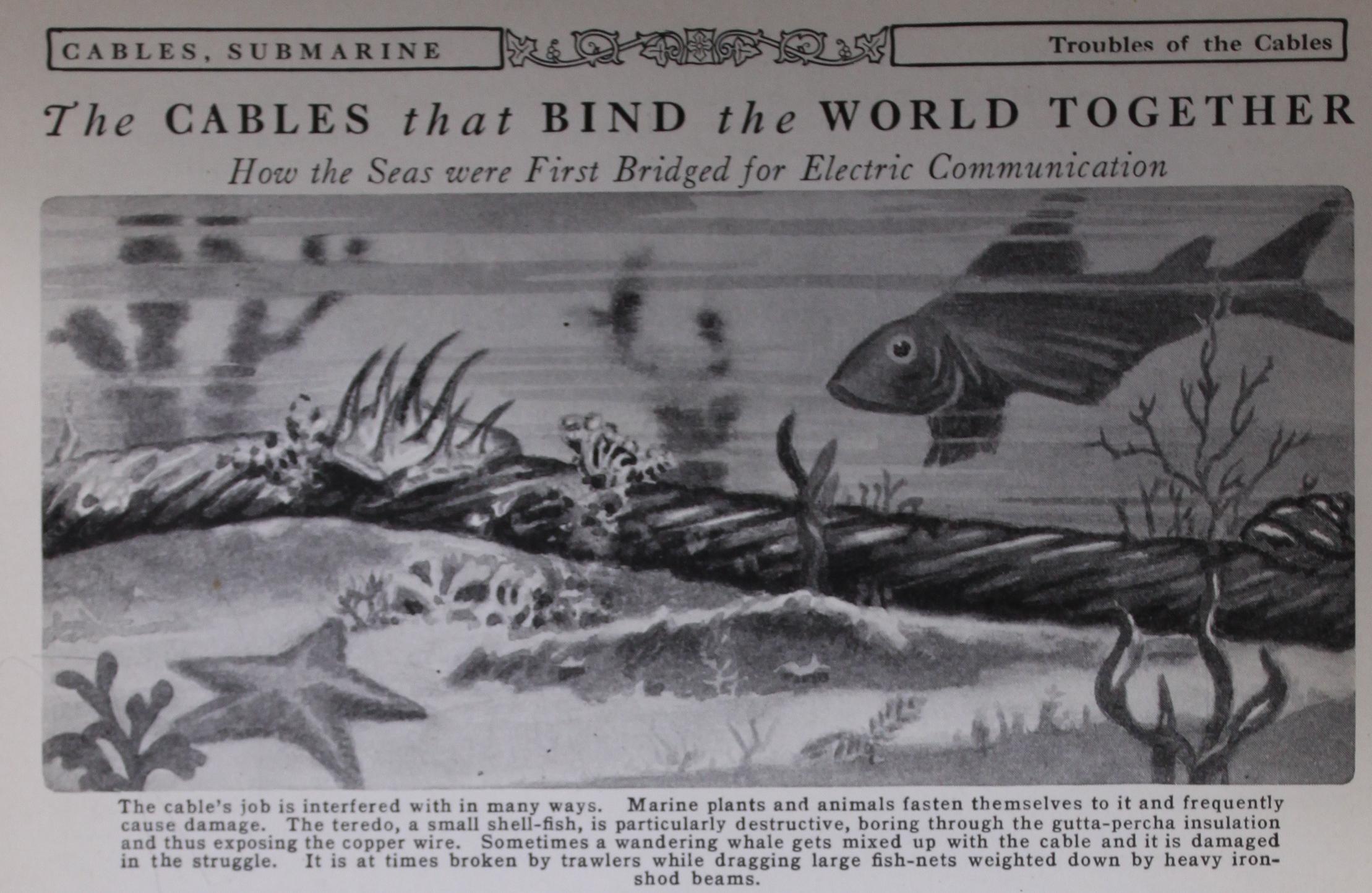

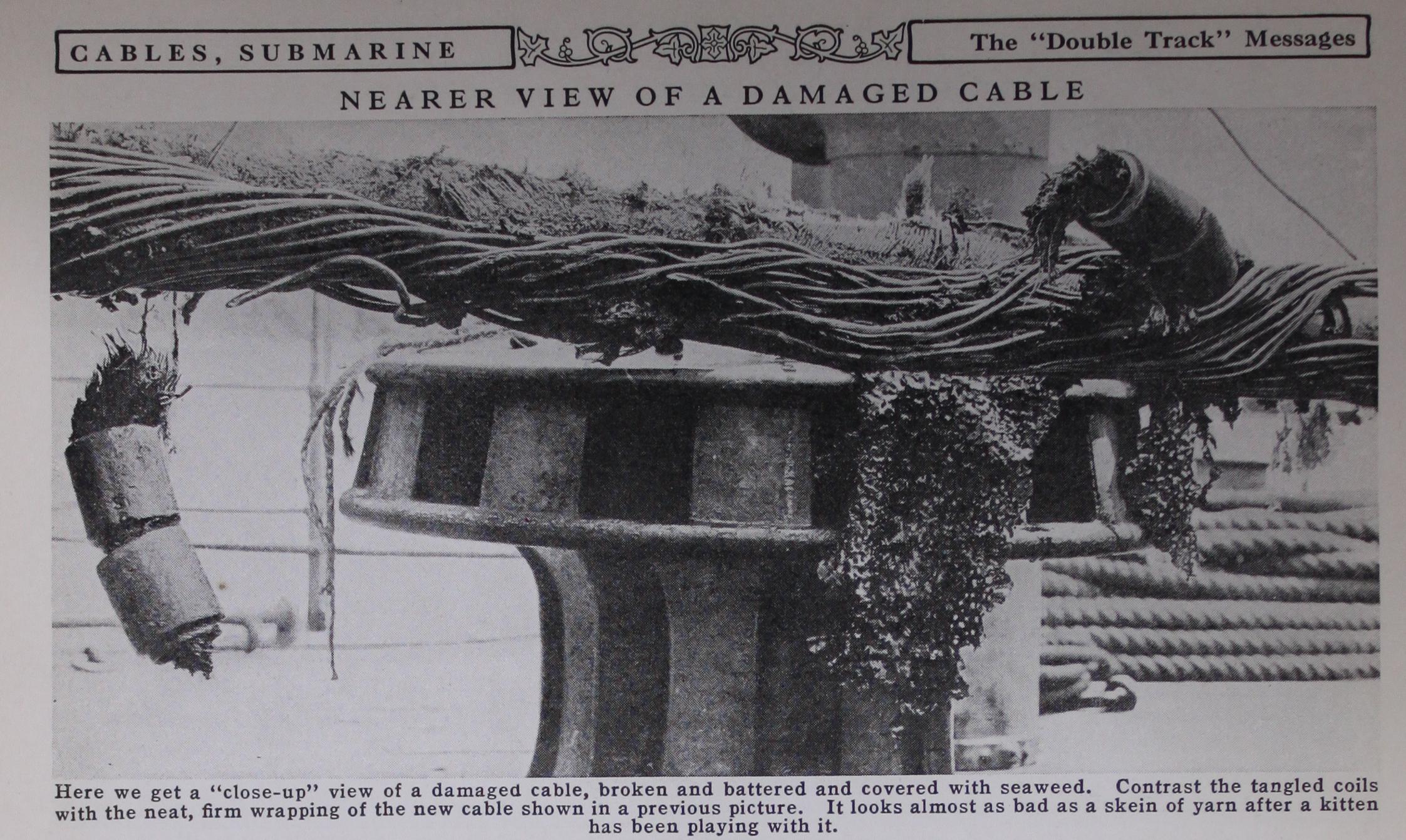

For one thing water is a good con ductor of electricity, and so the wire carrying the current under water must be very carefully insulated. The only effective material for this purpose is gutta-percha, which was fortunately introduced into this country and Europe soon after the invention of the telegraph, thus making submarine telegraphy possible. An ocean cable must also be

very strong and durable, to withstand injuries from rocks, ships' anchors, and the attacks of great fish like the shark and swordfish.

The cables used today consist of a core of seven or more copper wires, insulated by gutta percha and sur rounded by several layers of protective wrapping. This wrapping is made of layers of jute yarn, saturated with a bituminous compound, and a sheath of small cables each com posed of several strands of steel wire. In the deep sea less protection is necessary, and the weight of the cable runs from a ton to a ton and a half a mile. In shallow water the cable must be more heavily armored to protect it from rocks and dragging anchors, so the weight increases to 10 to 30 tons a mile. One of the most difficult prob lems which faced the early cable builders was to make the cable strong enough to bear this tremen dous weight as it was being lowered sometimes more than two miles to its bed; and time after time they were baffled by breaks in mid ocean.

When a current is transmitted over 2,000 or 3,000 miles of cable, much of the initial strength of the current is ex hausted by the resistance of the wire and the tendency of the gutta-percha insulation to retain a part of the charge. Hence it has been necessary to devise wonderfully delicate instruments, which will respond to much feebler currents than those used on land systems.

William Thomson, one of the greatest scientists of his time, who was later raised to the British peerage as Lord Kelvin in recognition of his wonderful services to science, invent ed a receiving instrument so deli cate that it received a message sent on a battery in a lady's thimble across the ocean through one cable and back through another.

His first instru ment was a gal vanometer in which a tiny mirror was moved from side to side, just as the magnetic needle of the ordinary galvanometer is moved, by changing the direction of the current passing over the circuit (see Electricity). A beam of light was directed upon the mirror so that the mir ror's slightest movement was indicated on a large scale by the movement of the reflected beam of light on a screen placed in front of the mirror. This mirror galvanometer was used in cabling until Lord Kelvin invented a record ing instrument, in which a peculiar pen, called the "siphon pen," was used.

A pen actually tracing on paper would be too heavy to be moved by the feeble currents, so Lord Kelvin used a pen so constructed that ink siphoned from an ink well is thrown in a tiny jet upon a paper moved regularly by clockwork.