Cell

cells, little, tiny, body, life, grow, called and time

CELL. No romancer ever dreamed of a magician or a wizard who could do things half so marvelous as the tiny cell, that drop of the mysterious sub stance we call protoplasm which has built up your body and the body of every human being and every animal and every plant that ever lived. The cell is the " once upon a time" with which the story of life begins. Though it is usually so tiny that it can not be seen without a powerful microscope, it has done more wonderful things than to turn pumpkins into gilded coaches and mice into horses. It didn't do them all at once, just by waving a wand. It began in a very humble way and took one small step at a time. At first it was contented to make another little round cell just like itself, then another and another and another, all as alike as so many peas. But each one of those cells full of proto plasm could eat and grow and make other little cells.

Then by and by, after ages and ages, because they were alive and their home wasn't always the same, some of the cells changed a little, and they kept on changing every time they had to. And so by changing and developing these cells have built up all the wonders of the living uni verse, from the tiny amoeba that consist of only one cell to creatures made up of millions upon millions of cells—the giant oak, the powerful elephant, and most wonderful of all—man himself (see Protoplasm).

These cells might he thought of as tiny living brick s joined together t o make up your body and the bodies of every living thing.

Though a few kinds of cells are fairly large — unfertilized eggs, for example, are single cells— most of them are so small that it takes 200 of them to make a line an inch long.

The cells that we know as bacteria are so tiny that it takes 25,000 of them to make an inch.

Cells are of many different shapes.

Some are globular, that is, like balls.

Some are cubical, some long and slender, some thin, flat, and platelike. Bone cells are rounded, often with projections; the cells of the outer skin are thin and flat ; muscle cells are long and cigar-shaped; while nerve cells may be very long and threadlike.

In spite of their great differences in form, however, all cells are composed of the soft jelly-like substance called protoplasm—the only form of matter in which life exists, and within which all the activities of life take place. Near the center of the cell is a small, denser, usually rounded mass of protoplasm called the nucleus, which seems to be the governing center.

Sometimes there are two nuclei, one large and one small. Within the nucleus are many small rodlike particles called the "chromosomes." These are very

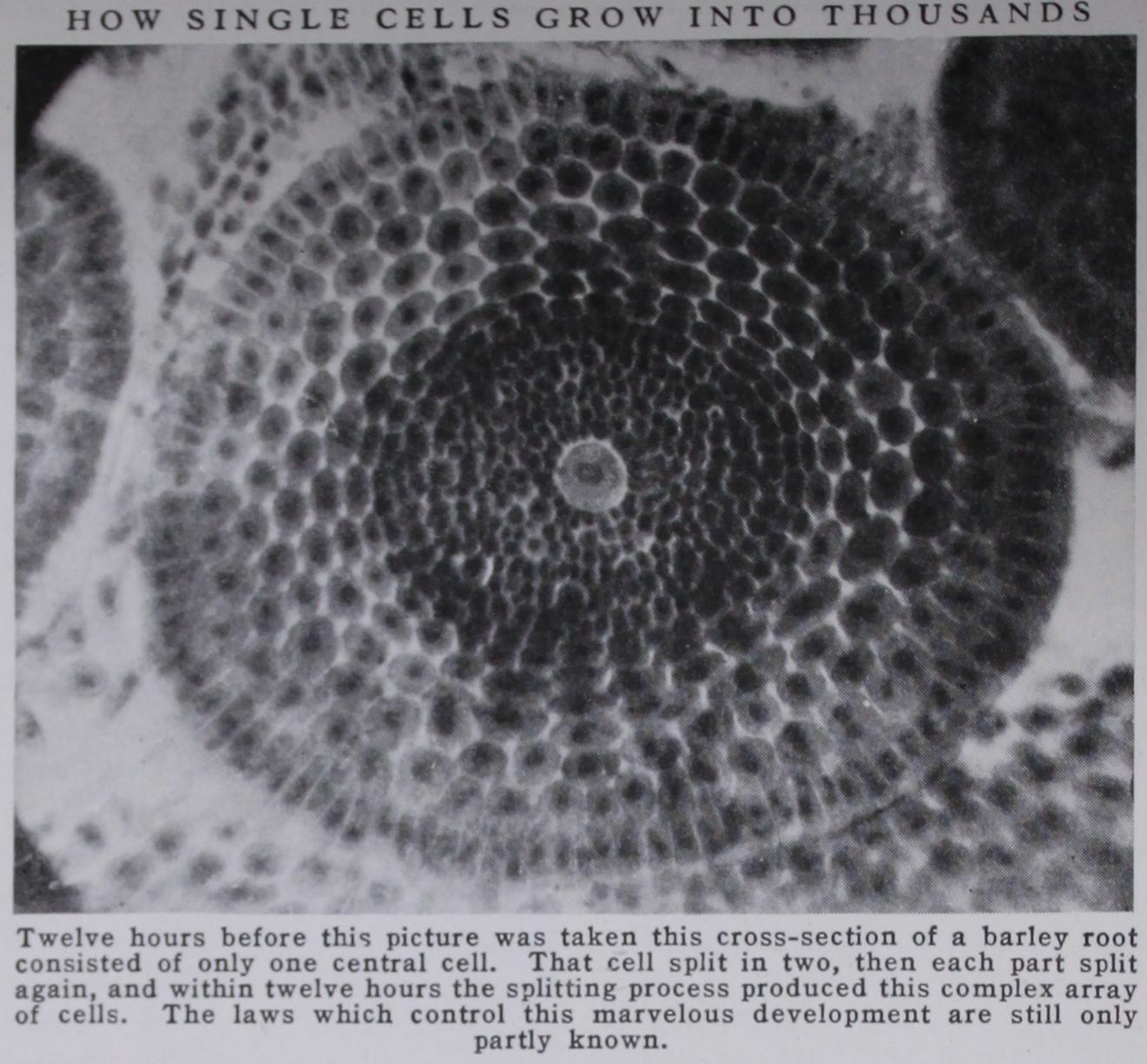

important little particles, too, for it is believed that they carry the hereditary peculiarities from one gener ation to another. (See Biology; Heredity.) How Cells Multiply by Division Cells multiply by splitting in half. Each chromo some splits into two pieces, one of which goes into one of the new cells, the other into the other. These new cells in turn divide, forming four; these split into eight, then 16, then 32, and so on. This is how a plant or animal grows, and as you can see, the number of cells soon grows to be very great. As new cells form, old ones are constantly being pushed off. The flaky white substance which comes off our bodies in the bath is nothing more than a mass of dead outer skin cells, which are cast off to make room for the new ones growing underneath. Some cells live only a few hours; others may live for years.

Cells do many different kinds of work. In animal bodies, for example, some cells pour out a limy sub stance which hard ens into bone, and thus the skeleton is built up. Still other cells mass them selves together and lengthen o u t t o form masses o f muscles to move these bones. Other cells grow very long and form nerves, while others grow thin and flat, and form a protective covering over the body, the skin.

The cells of the stomach and intes tines pour out digestive fluids, and the cells of the nose and throat produce mucus to keep those passages well moist ened.

In plants, likewise, the cells are set apart for many diverse kinds of labor. Some form stems, others leaves, others blossoms, and all have their charac teristic shape and produce their characteristic secre tions (that is, substances they pour out).