Cement

portland, lime, limestone, clay, rock, materials, white and chalk

CEMENT. Broadly speaking, cement is a term which may be applied to any substance used for making bodies adhere to each other. By far the most important class of cements is the hydraulic cements, which have the property, when they are mixed with water, of "setting" and finally becoming hard, even under water.

Three kinds of hydraulic cement are produced in the United States—portland cement, natural cement, and puzzolan, or slag cement; but the combined output of natural and puzzolan cement is now less than one per cent of the total production.

It was only about 50 years ago that the manufac ture of cement was taken up at all in the United States. Before that time all portland cement was imported from Europe. Up to 1900 natural cement was the chief kind manufactured and in 1905 only 1,000,000 barrels of portland cement were manu factured. Now the yearly output is a hundred times that amount.

Cement-Making Old as Egypt Nearly 4,000 years ago the Egyptians made a concrete that has stood the ravages of the centuries as if it were granite. The Greeks employed it to a limited extent, and the Romans made walls, aque ducts, roads, and monuments of it, which still stand.

The Roman cement was made from lime mixed with finely ground volcanic ash. Mixing and grinding suitable blast-furnace slag with burnt slaked lime gives the puzzolan cement of today, which is similar.

In 1824 portland cement was invented in England.

This is a compound of lime, silica, and alumina pro duced by grinding and mixing together some form of carbonate of lime with exactly the correct propor tion of clay, burning the mixture at a high heat, and grinding the resulting clinker to a powder. It was named portland cement because of its strong resem blance in color, hardness, and strength to the lime stone quarried at Portland, England. The raw materials commonly used are limestone, chalk, or marl, mixed with clay limestone or clay shale.

If a bed of limestone of uniform composition could be found containing exactly the right amount of clay, portland cement could be made by merely grinding and burning. But if there is the least variation from the correct proportions; the value of the cement will be greatly reduced. Most of the clay-bearing lime stones of the United States contain too much clay and some magnesia. If this rock is burned at the high temperature necessary for portland cement, it fuses to a useless slag. But if it is burned at a lower heat, it yields a soft yellow clinker. When this is ground it gives the so-called natural rock cement, manufac tured at Milwaukee, Wis., Akron, Ohio, and Louis ville, Ky. This lacks the great tensile strength of

portland cement, and is used for reservoir linings and other purposes where such strength is not needed.

Nearly every state in the Union has the raw materials for making portland cement, and so the manufacture is widely distributed. In the Lehigh Valley in Pennsylvania where the best materials are found and where 30 per cent of the cement produced in the country is manufactured, there is an unlimited deposit of slatelike limestone containing rather more clay than is required. To this a small amount of pure limestone is added. In England a comparatively soft chalk is generally used, and in Germany chalk lime stone and mergel (limestone clay). In New York, Ohio, and Michigan there are deposits similar to chalk. Through Indiana, Ohio, and Illinois are deposits of cement rock mixed with carbonate of lime.

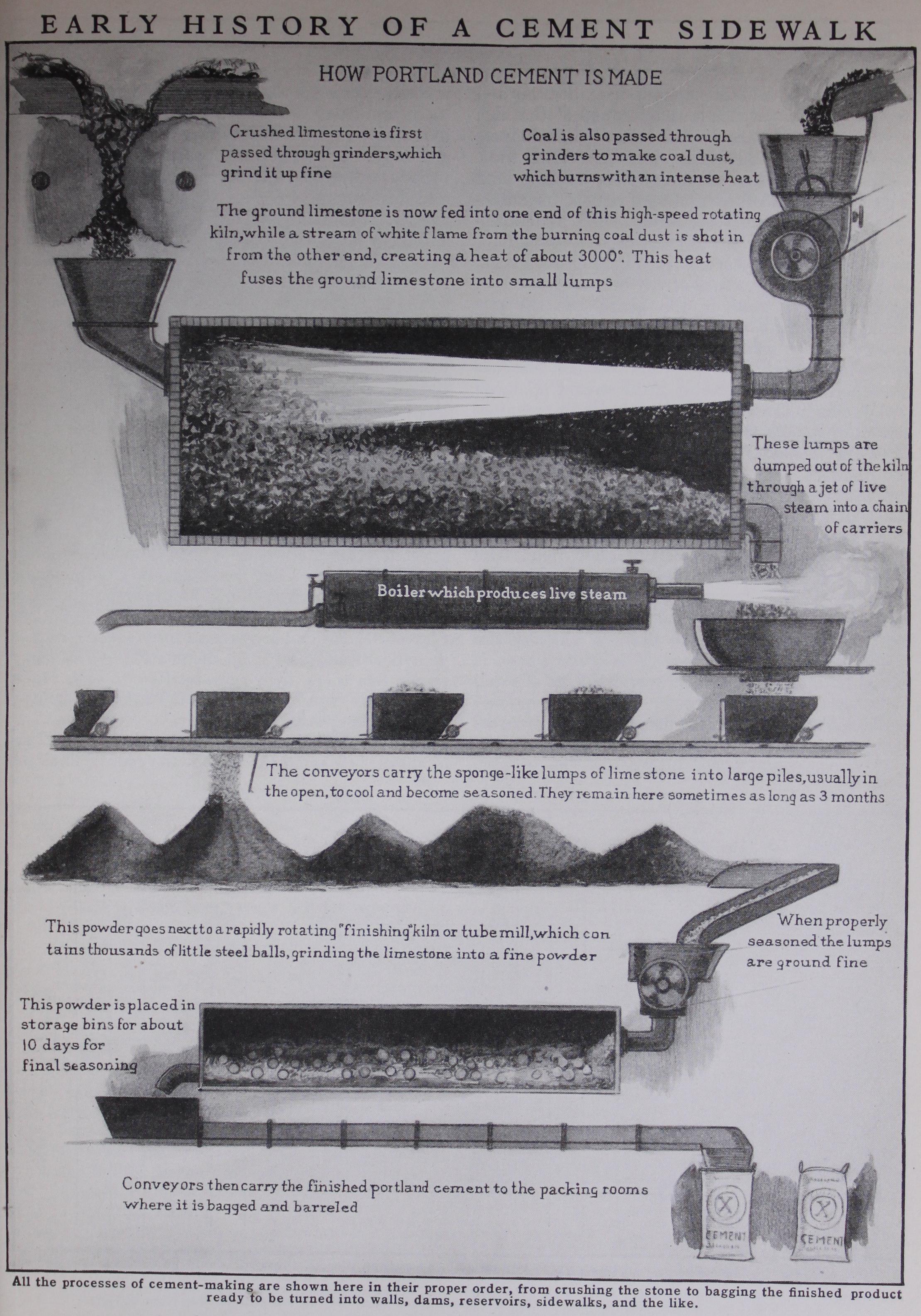

The manufacture of cement is an interesting process. In the dry process the raw materials are first crushed into fragments. This crushed rock is passed on into huge grinders carrying flails of steel, flying around at high speed. Here it is powdered until it looks like a dark gray flour. In other crushers and grinders coal is crushed and powdered.

Then comes the important part of the process.

This takes place in enormous rotary kilns—lined with firebrick—so large that a horse could walk through them, and from 60 to 220 feet long. These kilns are mounted on pivots and turned over and over at a great speed by cog gears. Into one end a torrent of rock dust is forced, and from the other end the burning coal dust comes in a great stream of white flame to meet it. In this intense heat the powdered rock melts and fuses into little pebbles as small as a pea or as large as a hazelnut. The glowing red pebbles fall on an endless bucket belt and are carried away to the cooling towers, where forced draughts of cold air blow upon them. This cement clinker then goes to another set of grinders which reduces it again to flour-like dust, which is the portland cement of commerce.

When the raw materials are not found in proper proportion, they are first ground wet, with the neces sary ingredients added to make the proportions cor rect. The mixture may be formed into bricks, which are then crushed and treated as described, or the wet "slurry" may be pumped directly into the kilns.

Pure white cement is made by using carefully selected white sand, white quartz, and white marble limestone. By adding small amounts of pigments many brilliant and lasting colors may be obtained.

(See Building Construction; Concrete.)