The Story of Don Quixote

knight, sancho, adventures, panza, giants, set, windmills and rosinante

THE STORY OF DON QUIXOTE. In a certain village of the province of La Mancha in Spain (so Cervantes tells us), there lived a quaint old gentleman about 50 years of age, tall, thin, and gaunt featured. His means were small, for he had sold many acres of land in order to buy tales of knight errantry. Whenever he was at leisure (which was nearly all the year round) he gave himself up to the reading of those ancient books of chivalry. They were mostly extravagant tales of impossibly noble and brave knights performing fantastic deeds of valor, but this foolish gentleman took them all for trite histories. His brain became so filled with all that he read of enchantments, quarrels, battles, wounds, wooings, loves, agonies, and all sorts of nonsense, that finally with much reading and little sleep he lost his wits. Then he hit upon the strangest notion that ever man of that time had, and that was to become a knight-errant himself, roaming the world over in full armor and on horseback, in quest of adventures like the knights of old.

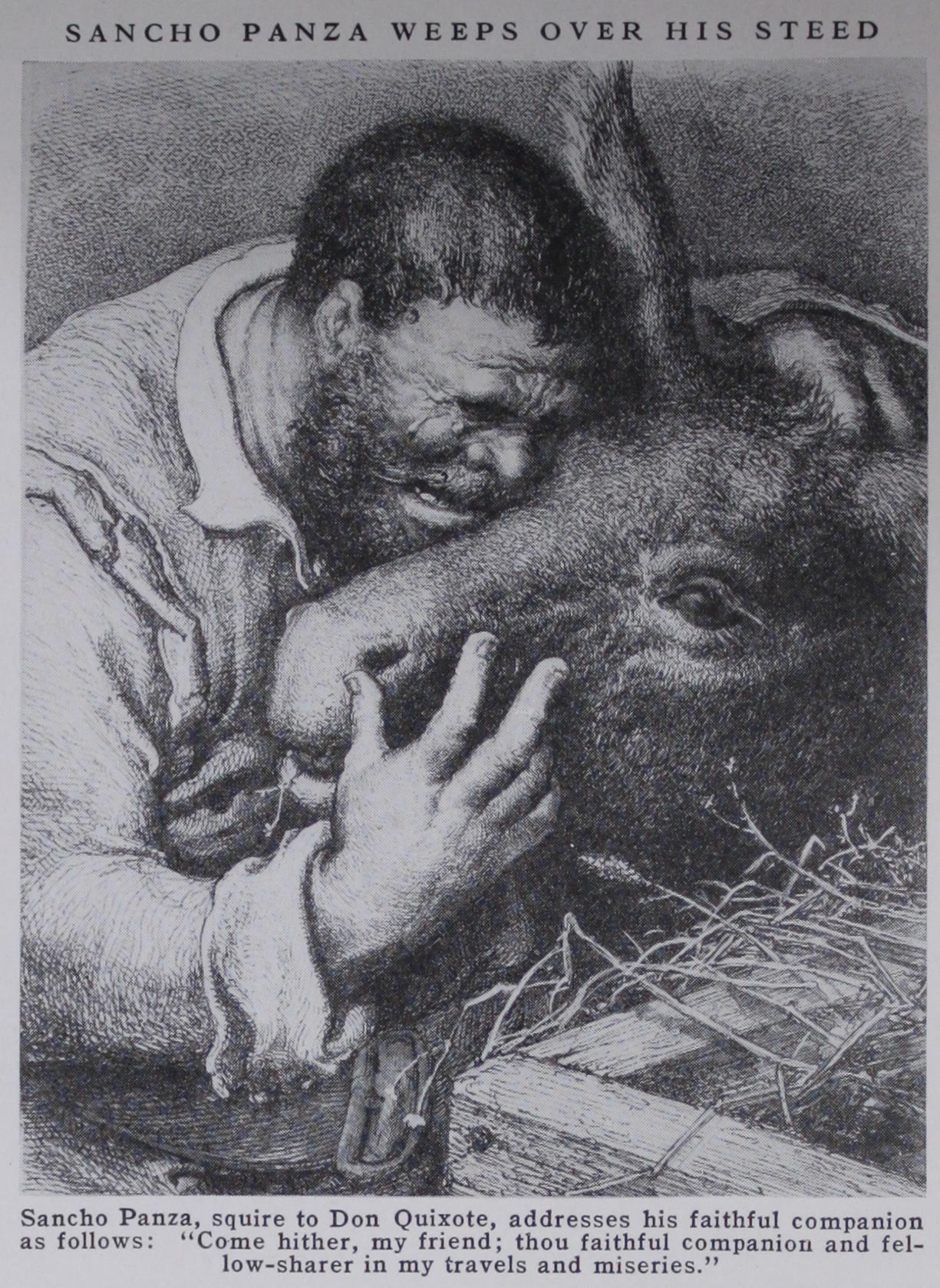

sounding title of Don Quixote de la Mancha. His sorry-looking old nag he named Rosinante, which meant " formerly a plough-horse." Of course a true knight must have a lady to be in love with, so he chose to honor a farmer's buxom daughter (whom he scarcely knew) and called her by the romantic and musical name of Dulcinea del Toboso. Deciding that he needed a squire to attend him, he engaged a short, fat farm laborer, named Sancho Panza, an honest, faithful clown of a fellow, whose wits were compounded of rustic ignorance arid shrewd common sense. In reward for Sancho's services, Don Quixote promised to make him governor of the first island or kingdom lie should conquer.

The Famous Attack on the Windmills So the melancholy knight on his raw-boned steed, followed by his comical squire on an ass, set forth upon their adventures. They had not been long on the road before they came in sight of 30 or 40 windmills on a plain.

"Look yonder," said Don Quixote, "more than 30 monstrous giants present themselves. I shall en counter and slay them, and with their spoils we will enrich ourselves, for it is fair war and a good service to sweep such evil fellows off the face of the earth." Rosinante and Sancho Panza So lie furbished up his great-grandfather's rusty armor, took lance and buckler, and adopted the high "What giants? What you see there are wind mills," said Sancho Panza in amazement.

"It is clear," answered Don Quixote, "that thou art not experienced in the business of adventures.

They are giants, and if thou art afraid, be take thyself to prayer while I engage them in fierce and unequal combat." Then set ting spurs to his steed, he cried out to the windmills: "Fly not, ye cowards and vile creatures, for it is but a single knight that attacks you!" Charging as fast as Rosinante could carry him, he fell full tilt upon the first mill.

But the wind whirled the sail around with such force that it shivered his lance, dragging after it horse and rider, who went rolling over and over on the plain.

Sancho Panza hast ened to his master's assistance. "Bless me! Did I not warn you they were only wind mills? No one could think otherwise unless he had something like windmills in his head." "Friend Sancho," replied Don Quixote, ruefully, "I verily believe these giants have been turned into mills in order to rob me of the glory of vanquishing them; but such wicked arts will avail but little against my good sword." Battered and bruised, but undismayed, the knight with some assistance remounted his lame old horse and rode away, still confident that he should find chances for knightly adventure.

Not long after this, he and Sancho Panza made their way to an inn. Don Quixote declared it was a castle, and acting accordingly, got himself into many absurd situations. And when he set out again he aroused the anger of the innkeeper by refusing to pay his bill, for, he said, it was contrary to the laws of knight errantry to pay for lodging or anything else. "Thou art a blockhead and a pitiful innkeeper," he said, clapping spurs to Rosinante. But poor Sancho's bones were made to pay for his master's folly, for the people of the inn seized him and tossed him in a blanket until he could hardly stand.

It would take too long to tell all Don Quixote's adventures, as he went about righting wrongs that did not exist or that he made worse by his misguided interfer ence—rescuing maid ens from supposed danger or distress, kill ing imaginary giants, and challenging in offensive wayfarers.

At length some of his friends, disguising themselves, went in search of him. They made the foolish knight believe that he himself was under enchantment, put him into a cage, and brought him home. But after a time Don Quixote and his squire again set out on yet another round of quaint adventures. But in the end he died at home and in his bed, with his weeping niece and friends about him—quite sane again, and crying out against the odious histories of knight-errantry which had led him to commit such follies.