Chemistry

salt, atoms, analysis, molecule, compound, chemical, oxygen, water and chemists

Attractions of the Chemist's Profession A tremendous future lies before any young man or woman who chooses the study of chemistry as a life work. Not only does the chemist's profession lead into paths of the utmost scientific interest, delving into the most fascinating of life's problems, but it has an intensely practical and profitable side.

Many of the comforts of life which we enjoy, much of the enormous progress in medicine and agriculture, are due to the chemist in his laboratory. - There is hardly a branch of industry which does not require the services of this keen-eyed, nimble-witted inves tigator. Steel-makers have their ores examined and every step in the process guarded by chemical analysis. Bakers employ chemists to aid them in buying the proper flour and in improving their processes of bread-making. Business houses buy their coal according to its fuel value as determined by chemistry. Rubber companies employ chemists to work out the best methods for improving their products. The meat-packing companies have an scientists claim that by means of this instrument some of the larger molecules, such as the molecule of albumen, have been observed. One of the most striking differences between the simple inorganic compounds such as salt and the highly complicated organic substances such as albumen is shown by the fact that, whereas the salt molecule consists of only two atoms, the albumen molecule contains more than 2,000, contributed by five different elements— hydrogen, carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and sulphur.

When we consider the ultimate constitution of atoms, we enter the field of physical chemistry and we have a new and mar velous world opened out to us. It is as though a wizard had drawn back the veil and shown us an Aladdin's cave of wonders.

The building up of atoms and molecules from elec trons—the constant move ment going on among these tiny particles, the marvel of radium and radio-active substances—all these come into the province of physi cal chemistry, which is per haps the most fascinating and the most romantic branch of all science (see Atoms and Electrons; Radium).

So rapid in succession are the discoveries made in this field that if a book is written today, embodying everything that is known, it is out of date in a year or two, for almost every week brings a new and important discovery.

The first law of chem istry is that matter cannot be destroyed. The most careful experiments have shown that no gain or loss of total weight takes place during any chemical change. There is an old trick question : "How can you weigh the smoke of a cigar?" to which the answer is: "Weigh the cigar before lighting it, and weigh the ashes afterward." In fact, this is no trick at all, -but the solid truth; for if the smoke and gases that escape could be weighed with the ashes they would exactly equal the weight of the original cigar, plus the oxygen that has been absorbed from the air during the burning.

This law, known as the "law of the conservation of matter," makes chemical analysis possible. A strange substance is submitted to a chemist, who is asked to tell what it is. He may burn it and collect the gases, or he may dissolve it in acids, or break it up into simpler forms in any one of a dozen different ways; but in the end, he will be able to tell you not only the different elements that made up the sub stance, but the proportion of each element, for noth ing is lost during the pro cess. If you put a silver spoon in strong nitric acid, it will dissolve and disap pear, but the metal has not been destroyed.

Every bit of it is still there in the liquid, and can easily be recovered and made into a spoon again of exactly the former size and weight.

If you take a piece of metal to a chemist and, after making his tests, he tells you simply that it is brass, made up of copper and zinc, you have an example of " qualitative analysis," which seeks only to determine the kind of chemicals in a substance. But if he makes further tests and tells you that the brass contains two-thirds cop per and one-third zinc, that is "quantitative analysis," which seeks to find out the quantity of each chemical. present.

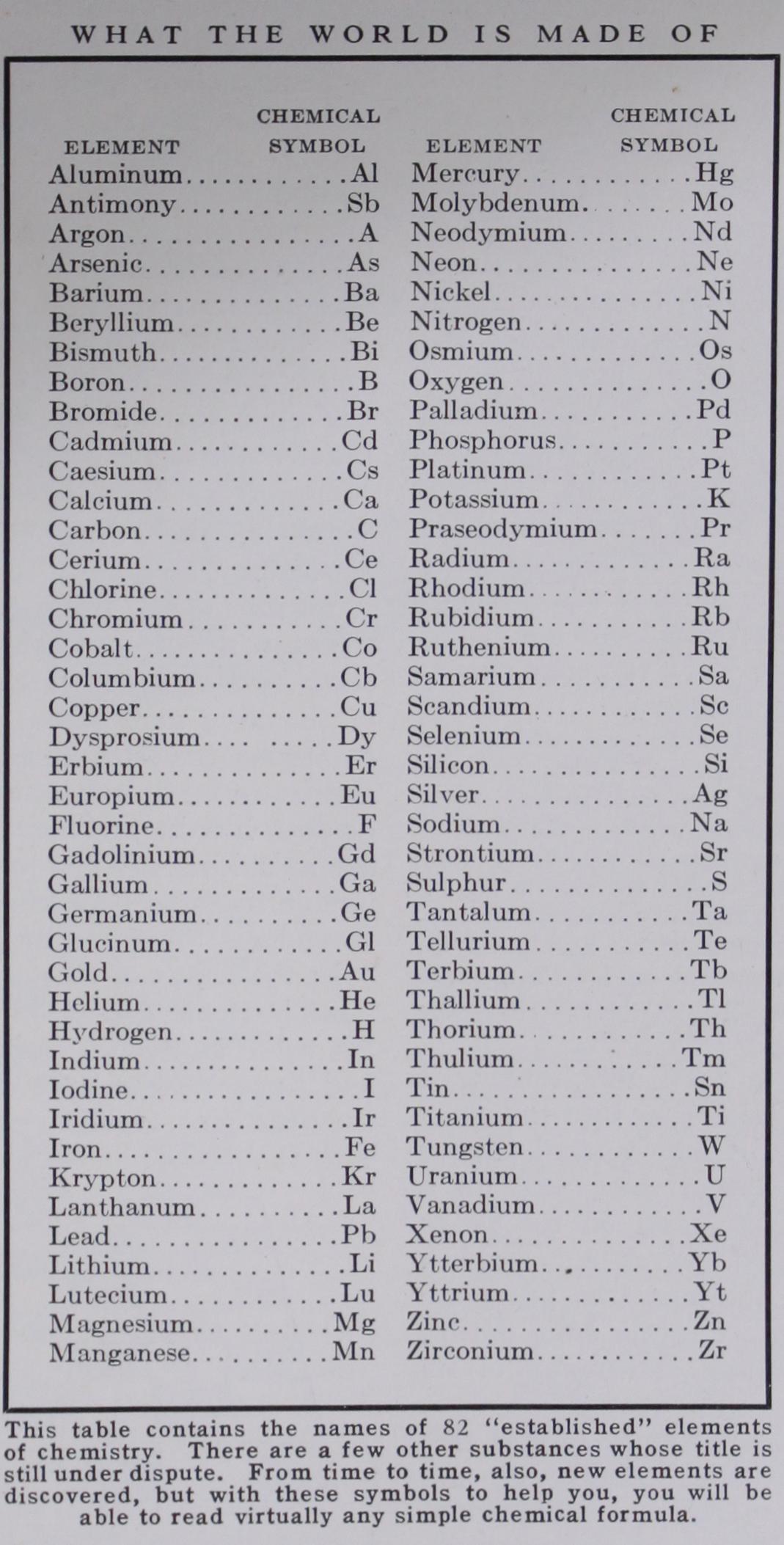

The chemist always writes down the results of any analysis in strange looking numbers and initials. These formulas, as they are called, are not half so mysterious as they appear, for each letter symbol stands for the name of some one of the 90 or so elements, and the small figures to the lower right of a letter indicate how many atoms there are of that particular element in the compound. The large figures before any letter or combination of letters show how many parts of that particular free element or compound are present.

Thus, if you should dissolve one teaspoonful of salt in 50 teaspoonfuls of water and have it analyzed, your answer would look like this: NaC1 +50 1120. Na is the symbol for sodium, CI the symbol for chlorine. When one atom of sodium unites and forms a compound with one atom of chlorine, that combination is indicated by the symbol NaCl, which is translated as one molecule of sodium chlo ride, the scientific name for common salt. Similarly the letter H stands for hydrogen and 0 stands for oxygen. But, in this case, two atoms of hydrogen (112) combine with one atom of oxygen to produce H20 or water, and the "50" indicates that for every molecule of salt there are 50 mole cules of water. The plus sign (+) dividing the salt and water in the formula shows that they formed a simple mixture and not a compound.