Maturation of Parthenogenetic Eggs

chromosomes and reduction

In all individuals arising from eggs of the first type, therefore, the somatic number of chromosomes is eighty-four ; in all those arising from eggs of the second type, it is one hundred and sixty-eight. It is impossible to doubt that the chromosomes of the first class are bivalent ; i.e. represent two chromosomes joined together — for that the dyads have this value is not a theory, but a known fact. It remains to be seen whether these facts apply to other parthenogenetic eggs ; but the single case of Artemia is little short of a demonstration not only of Hacker's and vom Rath's conception of bivalent chromosomes, but also of the more general hypothesis of the individuality of chromosomes (Chapter VI.). Only on this hypothesis can we explain the persistence of the original number of chromosomes, whether eighty-four or one hundred and sixty-eight, in the later stages. How important a bearing this case has on Strasburger's theory of reduction (p. 196) is obvious.

The one fact of maturation that stands out with perfect clearness and certainty amid all the controversies surrounding it is a reduction in the number of chromosomes in the ultimate germ-cells to one-half the number characteristic of the somatic cells. It is equally clear that this reduction is a preparation of the germ-cells for their subsequent union, and a means by which the number of chromosomes is held constant in the species. As soon, however, as we attempt to advance beyond this point we enter upon doubtful ground, which becomes more and more uncertain as we proceed. With a few exceptions the reduction in number first appears in the direct progenitors of the germ-cells by a segmentation of the spireme-thread into one-half the usual number of rods. This process is, however, not an actual reduction in the number of chromosomes, but only a preliminary " pseudo-reduction " in the number of chromatin-masses. In what we may regard as the typical case (e.g. Ascaris) the pseudo-reduction first appears at the penultimate division ; i.e. in the grandmother-cell of the germ-cell (primary oocyte or spermatocyte). It may, however, appear at a very much earlier period, even in the embryonic germ-cells, the reduced number appearing in every succeeding division until the germ-cells are formed. This is the case in the salamander and in Cyclops. It appears in its most striking form in the higher plants, where the reduced number appears in all the cells of the sexual generation (prothallium, pollen-tube, embryo-sac), beginning with the mother-cell of the asexual spores from which this generation arises.

In every case we must distinguish carefully between the primary pseudo-reduction in the number of chromatin-masses, and the actual reduction in the number of chromosomes ; for the former is in some cases certainly not an actual halving of the number of chromosomes, since each of the primary chromatin-rods is proved by its later history to be bivalent, representing two chromosomes united end to end (salamander, copepods). In these cases the actual reduction takes place

in the course of the last two divisions (formation of the polar bodies and of the spermatids), each bivalent chromatin-rod dividing transversely into the two chromosomes which it represents, and at the same time (or earlier) splitting lengthwise. Each primary rod thus gives rise to a tetrad consisting of two pairs of chromosomes which, by the two final divisions, are distributed one to each of the four resulting cells. In the copepods the first division separates the longitudinal halves of the chromosomes and is therefore an " equal division " (Weismann). The second division corresponds with the transverse division of the primary rod, and therefore is the "reducing division " postulated by Weismann.

This result gives a perfectly clear conception of the process of actual reduction and its relation to the preparatory pseudo-reduction that precedes it. It has, however, been absolutely demonstrated in only two groups of animals, viz. the copepods and the vertebrates (amphibia), and a diametrically opposite result has been reached in the case of Ascaris (Boveri, Hertwig, Brauer) and in the plants (Guignard, Strasburger). In Ascaris typical tetrads are formed, but all observers agree that they arise by a double longitudinal splitting of the original chromatin-rod. In the plants no tetrads have been observed, but the precise nature of the maturation-divisions is still in doubt.

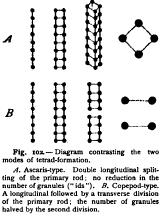

We have thus two diametrically opposing results. In the one case the primary halving in number is a pseudo-reduction, and each tetrad arises by one longitudinal and one transverse division of a bivalent chromosome, representing two different regions of the spireme-thread (Hacker, vom Rath, Ruckert, Weismann). In the other case the primary halving appears to be an actual reduction, and if tetrads are formed, they arise (Ascaris) by a double longitudinal splitting of the primary rod, and all of its four derivatives represent the same region of the spireme-thread. Since the latter consists primarily of a single series of granules (" ids " of Weismann, or chromomeres), by the fission of which the splitting takes place, the difference between the two views comes to this : that in the second case the four chromosomes of each tetrad must represent identical groups of granules, while in the first case they represent two different groups (Fig. 102). In the second case the maturation-divisions cannot cause a reduction in the number of different kinds of ids. In the first case the number of ids is reduced to one-half by the second division by which the second polar body is formed, or by which two spermatids arise from the daughter-spermatocyte (Ruckert, Hacker, vom Rath).