Morphological Composition of the Nucleus

chromosomes and division

MORPHOLOGICAL COMPOSITION OF THE NUCLEUS The Chromatin (a) Hypothesis of the Individuality of the Chromosomes. — It may now be taken as a well-established fact that the nucleus is never formed de novo, but always arises by the division of a preexisting nucleus. In the typical mode of division by mitosis the chromatic substance is resolved into a group of chromosomes, always the same in form and number in a given species of cell, and having the power of assimilation, growth, and division, as if they were morphological individuals of a lower order than the nucleus. That they are such individuals or units has been maintained as a definite hypothesis, especially by Rabl and Boveri. As a result of a careful study of mitosis in epithelial cells of the salamander, Rabl ('85) concluded that the chromosomes do not lose their individuality at the close of division, but persist in the chromatic reticulum of the resting nucleus. The reticulum arises through a transformation of the chromosomes, which give off anastomizing branches, and thus give rise to the appearance of a network. Their loss of identity is, however, only apparent. They come into view again at the ensuing division, at the beginning of which " the chromatic substance flows back, through predetermined paths, into the primary chromosomebodies " (Kernfaden), which reappear in the ensuing spireme-stage in nearly or quite the same position they occupied before. Even in the resting nucleus, Rabl believed that he could discover traces of the chromosomes in the configuration of the network, and he described the nucleus as showing a distinct polarity having a " pole " corresponding with the point towards which the apices of the chromosomes converge (i.e. towards the centrosome), and an " antipole " (Gegenpol) at the opposite point (i.e. towards the equator of the spindle) (Fig. r7). Rabl's hypothesis was precisely formulated and ardently advocated by Boveri in 1887 and 1888, and again in 1891, on the ground of his own studies and those of Van Beneden on the early stages of Ascaris. The hypothesis was supported by extremely strong evidence, derived especially from a study of abnormal variations in the early development of Ascaris, the force of which has, I think, been underestimated by the critics of the hypothesis. Some of this evidence may here be briefly reviewed. In some cases, through a miscarriage of the mitotic mechanism, one or both of the chromosomes destined for the second polar body are accidentally left in the egg. These chromosomes give rise in the egg to a reticular nucleus, indistinguishable from the egg-nucleus. At a later period this nucleus gives rise to the same number of chromosomes as those that entered into its formation ; i.e. either one or two. These are drawn into the equatorial plate along with those derived from the germ-nuclei, and mitosis proceeds as usual, the number of chromosomes being, however, abnormally increased from four to five or six (Fig. 103 C, D). Again, the two chromosomes left in the egg after removal of the second polar body may accidentally become separated. In this case each chromosome gives rise to a reticular nucleus of half the usual size, and from each of these a single chromosome is afterwards formed (Fig. 103, A, B). Finally, it sometimes happens that the two germ-nuclei completely fuse while in the reticular state, as is normally the case in sea-urchins and some other animals (p. 153). From the cleavage-nucleus thus formed arise four chromosomes.

These remarkable observations show that whatever be the number of chromosomes entering into the formation of a reticular nucleus, the same number afterwards issue from it —a result which demonstrates that the number of chromosomes is not due merely to the chemical composition of the chromatin-substance, but to a morphological organization of the nucleus. A beautiful confirmation of this conclusion

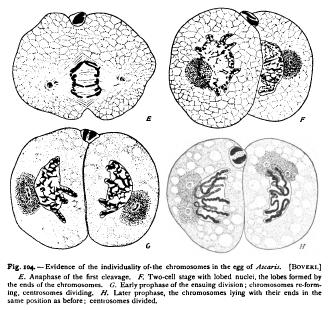

was afterwards made by Boveri ('93, '95, 1) and Morgan ('95, 4) in the case of echinoderms, by rearing larva from enucleated eggfragments, fertilized by a single spermatozoon (p. 258). All the nuclei of such larva contain but half the typical number of chromosomes, — i.e. nine instead of eighteen, — since all are descended from one germ-nucleus instead of two ! Van Beneden and Boveri were able, furthermore, to demonstrate in Ascaris that in the formation of the spireme the chromosomes reappear in the same position as those which entered into the formation of the reticulum, precisely as Rabl maintained. As the long chromosomes diverge, their free ends are always turned towards the middle plane (Fig. 24), and upon the reconstruction of the daughternuclei these ends give rise to corresponding lobes of the nucleus, as in Fig. 104, which persist throughout the resting state. At the succeeding division the chromosomes reappear exactly in the same position, their ends lying in the nuclear lobes as before (Fig. 104, G, H). On the strength of these facts Boveri concluded that the chromosomes must be regarded as " individuals " or " elementary organisms," that have an independent existence in the cell. During the reconstruction of the nucleus they send forth pseudopodia which anastomose to form a network in which their identity is lost to view. As the cell prepares for division, however, the chromosomes contract, withdraw their processes, and return to their " resting state," in which fission takes place. Applying this conclusion to the fertilization of the egg, Boveri expressed his belief that " we may identify every chromatic element arising from a resting nucleus with a definite element that entered into the formation of that nucleus, from which the remarkable conclusion follows that in all cells derived in the regular course of division from the fertilized egg, one-half of the chromosomes are of strictly paternal origin, the other half of Boveri's hypothesis has been criticised by many writers, especially by Hertwig, Guignard, and Brauer, and I myself have urged some objections to it. Recently, however, it has received a support so strong as to amount almost to a demonstration, through the remarkable observations of Ruckert, Hacker, Herla, and Zoja on the independence of the paternal and maternal chromosomes. These observations, already referred to at p. 156, may be more fully reviewed at this point. Hacker ('92, 2) first showed that in Cyclops strenuus, as in Ascaris and other forms, the germ-nuclei do not fuse, but give rise to two separate groups of chromosomes that lie side by side near the equator of the cleavage-spindle. In the two-cell stage (of Cyclops tenuicornis) each nucleus consists of two distinct though closely united halves, which Hacker believed to be the derivatives of the two respective germ-nuclei. The truth of this surmise was demonstrated three years later by Ruckert ('95, 3) in a species of Cyclops, likewise identified as C. strenuus (Fig. 105). The number of chromosomes in each germ-nucleus is here twelve. Ruckert was able to trace the paternal and maternal groups of daughter-chromosomes not only into the respective halves of the daughter-nuclei of the two-cell stage, but into later cleavage-stages. From the bilobed nuclei of the two-cell stage arises, in each cell, a double spireme, and a double group of chromosomes, from which are formed bilobed or double nuclei in the four-cell stage. This process is repeated at the next cleavage, and the double character of the nuclei was in many cases distinctly recognizable at a late stage when the germ-layers were being formed.