Origin of the Tetrads

division and tetrad

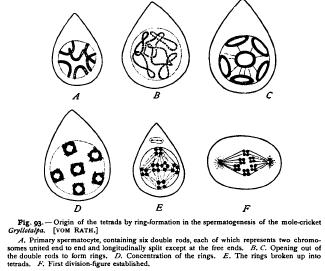

ORIGIN OF THE TETRADS General Sketch It is generally agreed that each tetrad arises by a double division of a single primary chromatin-rod. Nearly all observers agree further that the number of primary rods at their first appearance in the germinal vesicle or in the spermatocyte-nucleus is one-half the usual number of chromosomes, and that this numerical reduction is due to the fact that the spireme-thread segments into one-half the usual number of pieces. The contradiction relates to the manner in which the primary rod divides to form the tetrad. According to one account, mainly based on the study of Ascaris by Boveri, Hertwig, and Brauer, and supported in principle by the observations of Guignard and Strasburger on the flowering plants, each tetrad arises by a double longitudinal splitting of the primary chromatin-rod caused by the division of each chromatin-granule into four parts. In this case the four resulting bodies — i.e. the four chromosomes of the tetrad must be exactly equivalent, since all are derived from the same region of the spireme-thread and consist of equivalent groups of ids or chromatin-granules (Fig. 102, A). No reducing division can therefore occur in Weismann's sense. There is only a reduction in the number of chromosomes, not a reduction in the number of qualities represented by the chromatin-granules. This may be graphically expressed as follows :— If the original spireme-thread be represented by abcd, normal mitosis consists in its segmentation into the four chromosomes. a-b-c-d, which split lengthwise to form a/a, b/b, c/c, d/d.

In Maturation the thread segments into two portions, ab — cd, each of which then split into four equivalent portions, giving the equivalent tetrads, thus, ab/ab ab/ab and cd/cd cd/cd; or xx/xx, yy/yy, since it is not known whether ab really is equal to a + b.

The second account, which finds its strongest support in the observations of Ruckert, Hacker, and vom Rath on the maturation of arthropods, asserts that each tetrad arises by one longitudinal and one transverse division of each primary chromatin-rod (Fig. 102, B). Thus the spireme abed segments as before into two segments ab and cd. These first divide longitudinally to form ab/ab and cd/cd and then transversely to form ab/ab and cd/cd. Each tetrad therefore consists, not of four equivalent chromosomes, but of two different pairs ; and the second or transverse division by which a is separated from b, or c from d, is the reducing division demanded by Weismann's hypothesis. The observations of Ruckert and Hacker prove that the transverse division is accomplished during the formation of the second polar body.

Detailed Evidence

We may now consider some of the evidence in detail, though the limits of this work will only allow the consideration of some of the best known cases. We may first examine the case of Ascaris,on which the first account is based. In the first of his classical cell-studies Boveri showed that each tetrad appears in the germinal vesicle in the form of four parallel rods, each consisting of a row of chromatin-granules (Fig. 89, A—C). He believed these rods to arise by the double longitudinal splitting of a single primary chromatin-rod, each cleavage being a preparation for one of the polar bodies. In his opinion, therefore, the formation of the polar bodies differs from ordinary mitosis only in the fact that the chromosomes split very early, and not once, but twice, in preparation for two rapidly succeeding divisions without an intervening resting period. He supported this view by further observations in 1890 on the polar bodies of Sagitta and several gasteropods, in which he again determined, as he believed, that the tetrads arose by double longitudinal splitting. An essentially similar view of the tetrads was taken by Hertwig in 189o, in the spermatogenesis of Ascaris, though he could not support this conclusion by very convincing evidence. In 1893, finally, Brauer made a most thorough and apparently exhaustive study of their origin in the spermatogenesis of Ascaris, which seemed to leave no doubt of the correctness of Boveri's result. Every step in the origin of the tetrads from the reticulum of the resting spermatocytes was traced with the most painstaking care. The first step observed was a double splitting of the chromatin-threads in the reticulum, caused by a division of the chromatin-granules into four parts (Fig. 92, A). From the reticulum arises a continuous spireme-thread, which from its first appearance is split into four longitudinal parts, and ultimately breaks in two to form the two tetrads characteristic of the species. These have at first the same rod-like form as those of the germinal vesicle. Later they shorten to form compact groups, each consisting of four spherical chromosomes. Brauer's figures are very convincing, and, if correct, seem to leave no doubt that the tetrads here arise by a double longitudinal splitting of the spireme-thread, initiated even in the reticular stage before a connected thread has been formed. If this really be so, there can be here no reducing division in Weismann's sense. The reduction of chromatin, caused by the ensuing cell-division, is therefore only a quantitative mass-reduction, as Hertwig and Brauer insist, not a qualitative sundering of different elements, as Weismann's postulate demands.' The work of Strasburger and Guignard, considered at p. 195, has given in principle the same general result in the flowering plants, though the details of the process are here considerably modified, and apparently no tetrads are formed.