Origin of the Tetrads

division and chromosomes

We now return to the second view, referred to at p. 186, which accords with Weismann's hypothesis, and flatly contradicts the conclusions drawn from the study of Ascaris. This view is based mainly on the study of arthropods, especially the crustacea and insects, but has been confirmed by the facts observed in some of the lower vertebrata. In many of these forms the tetrads first appear in the form of closed rings, each of which finally breaks into four parts. First observed by Henking ('91) in the insect Pyrrochoris, they have since been found in other insects by vom Rath and Wilcox, in various cope1 In an earlier paper on Branchipus ('92) Brauer reached an essentially similar result, which was, however, based on far less convincing evidence.

pods by Ruckert, Hacker, and vom Rath, in the frog by vom Rath, and in elasmobranchs by Moore. The genesis of the ring was first determined by vom Rath in the mole-cricket (Gryllotalpa, '92), and has been thoroughly elucidated by the later work of Ruckert ('94) and Hacker ('95, i). All these observers, excepting Wilcox and Moore (see p. 204 have reached the same conclusion; namely, that the ring arises by the longitudinal splitting of a primary chromatinrod, the two halves remaining united by their ends, and opening out to form a ring. The ring-formation is, in fact, a form of hetcrotypical mitosis (p. 6o). The breaking of the ring into four parts involves first the separation of these two halves (corresponding with the original longitudinal split), and second, the transverse division of each half, the latter being the reducing division of Weismann. The number of primary rods, from which the rings arise, is one-half the somatic number. Hence each of them is conceived by vom Rath, Hacker, and Ruckert as bivalent or double ; i.e. as representing two chromosomes united end to end. This appears with the greatest clearness in the spermatogenesis of Gryllotalpa (Fig. 93). Here the spireme-thread splits lengthwise before its segmentation into rods. It then divides transversely to form six double rods (half the usual number of chromosomes), which open out to form six closed rings. These become small and thick, break each into four parts, and thus give rise to six typical tetrads. An essentially similar account of the ring-formation is given by vom Rath in Eucheta and Calanus, and by Ruckert in Heterocope and Diaptomus.

That the foregoing interpretation of the rings is correct, is beautifully demonstrated by the observations of Hacker, and especially of Ruckert, on a number of other copepods (Cyclops, Canthocamptus), in which rings are not formed, since the splitting of the primary chromatin-rods is complete. The origin of the tetrads has here been traced with especial care in Cyclops strenuus, by Ruckert ('94), whose observations, confirmed by Hacker, are quite as convincing as those of Brauer on Ascaris, though they lead to a diametrically opposite result.

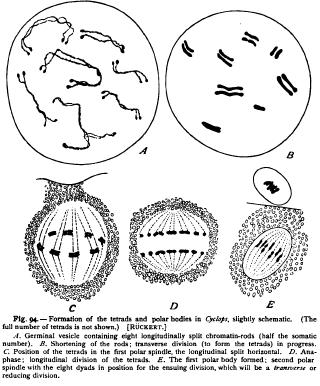

The normal number of chromosomes is here twenty-two. In the germinal vesicle arise eleven threads, which split lengthwise (Fig. 94), and finally shorten to form double rods, manifestly equivalent to the closed rings of Diaptomus. Each of these now segments transversely to form a tetrad group, and the eleven tetrads then place themselves in the equator of the spindle for the first polar body (Fig. 94, C), in such

a manner that the longitudinal split is transverse to the axis of the spindle. As the polar body is formed, the longitudinal halves of the tetrad separate, and the formation of the first polar body is thus demonstrated to be an " equal division " in Weismann's sense. The eleven dyads remaining in the eggs now rotate (as in Ascaris), so that the transverse division lies in the equatorial plane, and are halved during the formation of the second polar body. The division is accordingly a " reducing division," which leaves eleven single chromosomes in the egg, and it is a curious fact that this conclusion, which apparently rests on irrefragable evidence, completely confirms Weismann's earlier views, published in and contradicts the later interpretation upheld in his book on the germ-plasm.

Hacker ('92) has reached exactly similar results in the case of Canthocamptus and draws the same conclusion. In Cyclops strenuus he finds in the case of first-laid eggs a variation of the process which seems to approach the mode of tetrad formation in some of the lower vertebrates. In such eggs the primary double rods become sharply bent near the middle to form V-shaped loops (Fig. 96, C), which finally break transversely near the apex to form the tetrad a process which clearly gives the same result as before. An exactly similar process seems to occur in the salamander as described by Flemming and vom Rath. Flemming observed the double V-shaped loops in 1887, and also the tetrads derived from them, but regarded the latter as " anomalies." Vom Rath ('93) subsequently found that the double V's break at the apex, and that the four rods thus formed then draw together to form four spheres grouped in a tetrad precisely like those of the arthropods. Still later ('95, I) the same observer traced a nearly similar process in the frog ; but in this case the four elements appear to remain for a short time united to form a ring before breaking up into separate spheres.

To sum up : The researches of Ruckert, Hacker, and vom Rath, on insects, crustacea, and amphibia have all led to the same result. However the tetrad-formation may differ in matter of detail, it is in all these forms the same in principle. Each primary chromatin-rod has the value of a bivalent chromosome ; i.e. two chromosomes joined end to end, ab. By a longitudinal division a ring or double rod is formed, which represents two equivalent pairs of chromosomes ab/ab.

During the two maturation-divisions the four chromosomes are split apart ab/ab,and Ruckert's observations demonstrate that the first division separates the two equivalent dyads, ab and ab, which by the second division are split apart into the two separate chromosomes, a and b. Weismann's postulate is accordingly realized in the second division. It is clear from this account that the primary halving of the number of chromatin-rods is not an actual reduction, since each rod represents two chromosomes. Ruckert therefore proposes the convenient term " pseudo-reduction " for this preliminary halving.' The actual reduction is not effected until the dyads are split apart during the second maturation-division.