Promorphological Relations of Cleavage

egg and development

(b) Axial Relations of the Primary Cleavage-planes.—Since the egg-axis is definitely related to the embryonic axes, and since the first two cleavage-planes pass through it, we may naturally look for a definite relation between these planes and the embryonic axes ; and if such a relation exists, then the first two or four blastomeres must likewise have a definite prospective value in the development. Such relations have, in fact, been accurately determined in a large number of cases. The first to call attention to such a relation seems to have been Newport ('54), who discovered the remarkable fact that the first cleavage-plane in the frog's egg coincides with the median plane of the adult body; that, in other words, one of the first two blastomeres gives rise to the left side of the body, the other to the right. This discovery, though long overlooked and, indeed, forgotten, was confirmed more than thirty years later by Pluger and Roux ('87). It was placed beyond all question by a remarkable experiment by Roux ('88), who succeeded in killing one of the blastomeres by puncture with a heated needle, whereupon the uninjured cell gave rise to a half-body as if the embryo had been bisected down the middle line (Fig. 131).

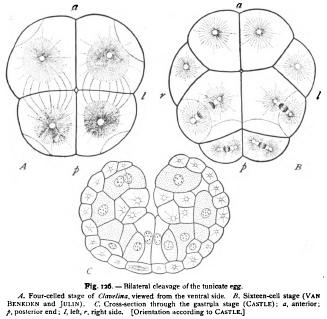

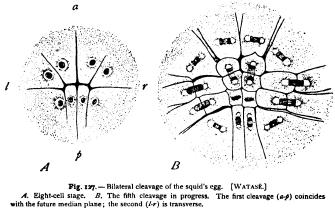

A similar result has been reached in a number of other animals by following out the cell-lineage ; e.g. by Van Beneden and Julin ('84) in the egg of the tunicate Clavelina (Fig. 126), and by Watase ('91) in the eggs of cephalopods (Fig. 127). In both these cases all the early stages of cleavage show a beautiful bilateral symmetry, and not only can the right and left halves of the segmenting egg be distinguished with the greatest clearness, but also the anterior and posterior regions, and the dorsal and ventral aspects. These discoveries seemed, at first, to justify the hope that a fundamental law of development had been discovered, and Van Beneden was thus led, as early as 1883, to express the view that the development of all bilateral animals would probably be found to agree with the frog and ascidian in respect to the relations of the first cleavage.

This conclusion was soon proved to have been premature. In one series of forms, not the first but the second cleavage-plane was found to coincide with the future long axis (Nerds, and some other annelids ; Crepidula, Umbrella, and other gasteropods). In another series of forms neither of the first cleavages passes through the median plane, but both form an angle of about 45° to it (Clepsine and other leeches ; Rhynchelmis and other annelids ; Planorbis, Nassa, Unio, and other mollusks ; Discoca'lis and other platodes). In a few cases the first cleavage departs entirely from the rule, and is equatorial, as in Ascaris and some other nematodes. The whole subject was finally thrown into apparent confusion, first by the discovery of Clapp (90, Jordan, and Eycleshymer ('94) that in some cases there seems to be no constant relation whatever between the early cleavage-planes and the adult axes, even in the same species (teleosts, urodeles) ; and even in the frog Hertwig showed that the relation described by Newport and Roux is not invariable. Driesch finally demonstrated that the direction of the early cleavage-planes might be artificially modified by pressure without perceptibly affecting the end-result (cf. p. 309).

These facts prove that the promorphology of the early cleavageforms can have no fundamental significance. Nevertheless, they are of the highest interest and importance ; for the fact that the formative forces by which development is determined may or may not coincide with those controlling the cleavage, gives us some hope of disentangling the complicated factors of development through a comparative study of the different forms.

(c) Other Promorphological Characters of the Ovum. — Besides the

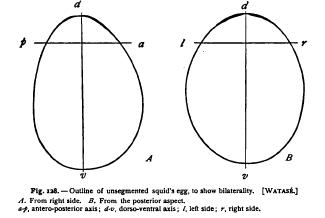

polarity of the ovum, which is the most constant and clearly marked of its promorphological features, we are often able to discover other characters that more or less clearly foreshadow the later development. One of the most interesting and clearly marked of these is the bilateral symmetry of the ovum in bilateral animals, which is sometimes so clearly marked that the exact position of the embryo may be predicted in the unfertilized egg, sometimes even before it is laid. This is the case, for example, in the cephalopod egg, as shown by Watase (Fig. 128). Here the form of the new-laid egg, before cleavage begins, distinctly foreshadows that of the embryonic body, and forms as it were a mould in which the whole development is cast. Its general shape is that of a hen's egg slightly flattened on one side, the narrow end, according to Watase, representing the dorsal aspect, the broad end the ventral aspect, the flattened side the posterior region, and the more convex side the anterior region. All the early cleavagefurrows are bilaterally arranged with respect to the plane of symmetry in the undivided egg; and the same is true of the later development of all the bilateral parts.

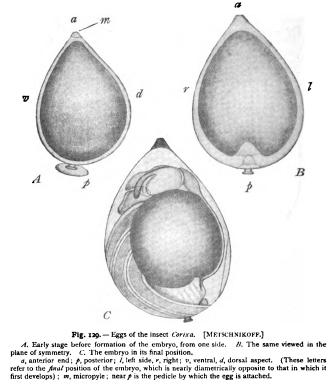

Scarcely less striking is the case of the insect egg, as has been pointed out especially by Hallez, Blochmann, and Wheeler (Figs. 44, 129). In a large number of cases the egg is elongated and bilaterally symmetrical, and, according to Blochmann and Wheeler, may even show a bilateral distribution of the yolk corresponding with the bilaterality of the ovum. Hallez asserts as the result of a study of the cockroach (Periplaneta), the water-beetle (Hydrophilus), and the locust (Locusta) that " the egg-cell possesses the same orientation as the maternal organism that produces it ; it has a cephalic pole and a caudal pole, a right side and a left, a dorsal aspect and a ventral ; and these different aspects of the egg-cell coincide with the corresponding aspects of the embryo." Wheeler ('93), after examining some thirty different species of insects, reached the same result, and concluded that even when the egg approaches the spherical form the symmetry still exists, though obscured. Moreover, according to Hallez ('86) and later writers, the egg always lies in the same position in the oviduct, its cephalic end being turned forwards towards the upper end of the oviduct, and hence towards the head-end of the mother.' Meaning of the Promorphology of the Ovum The interpretation of the promorphology of the ovum cannot be adequately treated apart from the general discussion of development given in the following chapter ; nevertheless it may conveniently be considered at this point. Two fundamentally different interpretations of the facts have been given. On the one hand, it has been suggested by Flemming and Van and urged especially by that the cytoplasm of the ovum possesses a definite primordial organization which exists from the beginning of its existence even though invisible, and is revealed to observation through polar differentiation, bilateral symmetry, and other obvious characters in the unsegmented egg. On the other hand, it has been maintained by Pfluger, Mark, Oscar Hertwig, Driesch, Watase, and the writer that all the promorphological features of the ovum are of secondary origin ; that the egg-cytoplasm is at the beginning isotropous — i.e. indifferent or homaxial — and gradually acquires its promorphological features during its pre-embryonic history. Thus the egg of a bilateral animal is not at the beginning actually, but only potentially, bilateral. Bilaterality once established, however, it forms as it were the mould in which the cleavage and other operations of development are cast.