Promorphological Relations of Cleavage

egg and ovum

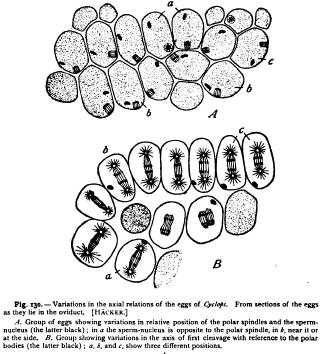

I believe that the evidence at our command weighs heavily on the side of the second view, and that the first hypothesis fails to take sufficient account of the fact that development does not necessarily begin with fertilization or cleavage, but may begin at a far earlier period during ovarian life. As far as the visible promorphological features of the ovum are concerned, this conclusion is beyond question. The only question that has any meaning is whether these visible characters are merely the expression of a more subtle preexisting invisible organization of the same kind. I do not believe that this question can be answered in the affirmative save by the trite and, from this point of view, barren statement that every effect must have its pre-existing cause. That the egg possesses no fixed and predetermined cytoplasmic localization with reference to the adult parts, has, I think, been demonstrated through the remarkable experiments of Driesch, Roux, and Boveri, which show that a fragment of the egg may give rise to a complete larva (p. 3o8). There is strong evidence, moreover, that the egg-axis is not primordial, but is established at a particular period ; and even after its establishment it may be entirely altered by new conditions. This is proved, for example, by the case of the frog's egg, in which, as Pfluger ('84), Born ('85), and Schultze ('94) have shown, the cytoplasmic materials may be entirely re-arranged under the influence of gravity, and a new axis established. In sea-urchins, my own observations ('95) render it probable that the egg-axis is not finally established until after fertilization. Finally, it is becoming more and more doubtful whether the relation of the egg-axis to the adult axis has so deep a significance as was at first assumed. This relation has been found to vary not only in nearly related forms (insects), but even in the same species (Ascaris, according to Boveri and others ; Toxopneustes, according to my own observations ; copepods, according to Hacker).

All these and many other similar facts force us, I think, to the conclusion that the promorphological features of the egg are as truly a result of development as the characters coming into view at later stages. They are gradually established during the pre-embryonic stages, and the egg, when ready for fertilization, has already accomplished part of its task by laying the basis for what is to come.

Mark; who was one of the first to examine this subject carefully, concluded that the ovum is at first an indifferent or homaxial cell (i.e. isotropic), which afterwards acquires polarity and other promorphological The same view was very precisely formulated by Watase in 1891, in the following statement, which I believe to express accurately the truth : " It appears to me admissible to say at present that the ovum, which may start out without any definite axis at first, may acquire it later, and at the moment ready for its cleavage the distribution of its protoplasmic substances may be such as to exhibit a perfect symmetry, and the furrows of cleavage may have a certain definite relation to the inherent arrangement of the protoplasmic substances which constitute the ovum. Hence, in a certain case, the plane of the first cleavage-furrow may coincide with the plane of the median axis of the embryo, and the sundering of the protoplasmic material may take place into right and left, according to the pre-existing organization of the egg at the time of cleavage ; and in another case the first cleavage may roughly correspond to the differentiation of the ectoderm and the entoderm, also according to the pre-organized constitution of the protoplasmic materials of the ovum.

" It does not appear strange, therefore, that we may detect a certain structural differentiation in the unsegmented ovum, with all the axes foreshadowed in it, and the axial symmetry of the embryonic organism identical with that of the This passage contains, I believe, the gist of the whole matter, as far as the promorphological relations of the ovum and of cleavageforms are concerned, though Watase does not enter into the question as to how the arrangement of protoplasmic materials is effected. In

considering this question, we must hold fast to the fundamental fact that the egg is a cell, like other cells, and that from an a priori point of view there is every reason to believe that the cytoplasmic differentiations that it undergoes must arise in essentially the same way as in other cells. We know that such differentiations, whether in form or in internal structure, show a definite relation to the environment of the cell — to its fellows, to the source of food, and the like. We know further, as Korschelt especially has pointed out, that the eggaxis, as expressed by the eccentricity of the germinal vesicle, often shows a definite' relation to the ovarian tissues, the germinal vesicle lying near the point of attachment or of food-supply. Mark made the pregnant suggestion, in 1881, that the primary polarity of the egg might be determined by "the topographical relation of the cgg (when still in an indifferent state) to the remaining cells of the maternal tissue from which it is differentiated," and added that this relation might operate through the nutrition of the ovum. " It would certainly be interesting to know if that phase of polar differentiation which is manifest in the position of the nutritive substance and of the germinal vesicle bears a constant relation to the free surface of the epithelium from which the egg takes its origin. If, in cases where the egg is directly developed from epithelial cells, this relationship were demonstrable, it would be fair to infer the existence of corresponding, though obscured, relations in those cases where (as, for example, in mammals) the origin of the ovum is less directly traceable to an epithelial The polarity of the egg would therefore be comparable to the polarity of epithelial or gland cells, where, as pointed out at p. 40, the nucleus usually lies towards the base of the cell, near the source of food, while the characteristic cytoplasmic products, such as zymogen granules and other secretions, appear in the outer The exact conditions under which the ovarian egg develops are still too little known to allow of a positive conclusion regarding Mark's suggestion. Moreover, the force of Korschelt's observation is weakened by the fact that in many eggs of the extreme telolecithal type, where the polarity is very marked, the germinal vesicle occupies a central or sub-central position during the period of yolk-formation and only moves towards the periphery near the time of maturation.

Indeed, in mollusks, annelids, and many other cases, the germinal vesicle remains in a central position, surrounded by yolk on all sides, until the spermatozoon enters. Only then does the egg-nucleus move to the periphery, the deutoplasm become massed at one pole, and the polarity of the egg come into view (Nereis, Figs. 43 and In such cases the axis of the egg is not improbably predetermined by the position of the centrosome, and we have still to seek the causes by which the position is established in the ovarian history of the egg. These considerations show that the problem is a complex one, involving, as it does, the whole question of cell-polarity ; and I know of no more promising field of investigation than the ovarian history of the ovum with reference to this question. That Mark's view is correct in principle is indicated by a great array of general evidence considered in the following chapter, where its bearing on the general theory of development is more fully dealt with.