American Glass

AMERICAN GLASS The development of American glass-making from both corn mercial and aesthetic standpoints is unlike that of ancient, oriental or European endeavours in the same field. From the semi-mythical period to the present day, the industry has encountered almost insurmountable handicaps and has had to solve problems in respect to glass manufacture different from those of other lands. Strin gent migration laws from Old World glass houses, regarding their workers, resulted in a great scarcity of operatives for early American furnaces; the assistance and patronage of guilds and trades societies enjoyed by European artisans was non-existent in the United States ; poor pot-clay and silica bed ingredients, the constant recurrence of conflagrations, an apathetic attitude on the part of the general public during the 17th and 18th centuries, and the tendency of the workmen to turn agriculturists, doomed nearly every attempt to failure almost before it had started.

As it happened, the i 7th century was almost a glassless age in the American Colonies. Men lived and died in the more isolated sections without ever having seen the substance called glass. It is not definitely known what furnaces made the first window-panes, 1629 being the earliest record of glass for this purpose brought from England by the settlers. Many 17th century households were equipped with durable pewter, wooden and iron utensils; crude glass bottles, bowls, pans and pitchers were more of a luxury than a necessity.

America was so busily engaged in the matter of expansion, civilization and upbuilding, in the preservation of life itself, that the cultural aspects of many of the arts and crafts were neglected. In time, the more well-to-do sent to Europe for their drinking glasses and decanters, and the tide of imports gradually increased Native sporadic endeavours could not compete in quality or quantity with foreign production.

The earliest glass furnaces were situated along the Atlantic sea board, the first attempt at glass-making being in the spring of 1609. The previous autumn, the London company sent eight Dutch and Polish glass-blowers to Jamestown, Va., who began the manufacture of crude articles for the settlers and for exportation purposes, Robert Mansell not having yet received his patent for sea-coal as a fuel for glass furnaces in England. Extant records state that this production was the first made-in-America article to be exported. The operations were short-lived. The next attempt was promoted by the same company in 1621 when Venetian work men were sent over from London for the purpose of fabricating beads used for barter with the Indians in return for large tracts of their land. After several years the undertaking collapsed. A few remains of these round and cylindrical coloured beads have survived. This may be called America's first mint. Salem, Mass., was the seat of the third brief experiment. In 1641 Obadiah Holmes and Lawrence Southwick built a primitive plant wherein, it is thought, window-panes and roundels, coarse bowls, bottles, pitchers and lamps were blown intermittently for two or three years.

The first centralized industry was in the Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam on Manhattan island, where glass was probably manufactured continuously from 1645 to 1767. The earliest fur naces were built on Glass Makers street (now William street), the later ones several miles further northward, at the Glass House Farm situated on the Hudson river. Johannes Smedes, Cornelis Dirkson, members of the Jansen and Melyn- families, and other Dutch artisans also practised the art of glass-blowing in New York. Evert Duycking and his son Gerrit made America's first coloured art glass for the windows of the Dutch Reformed and other churches in the vicinity between 1654 and 1674.

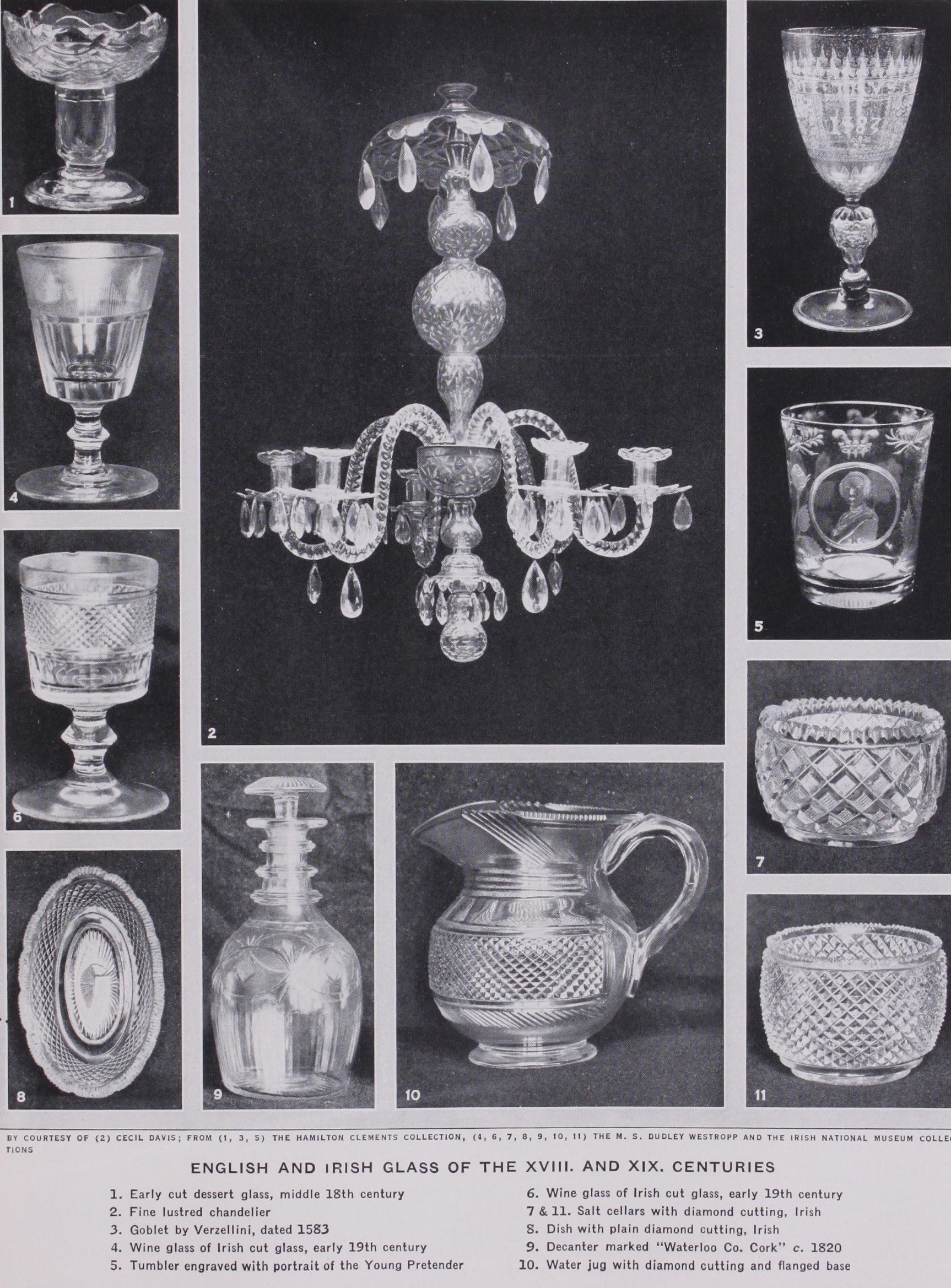

The majority of the glass-house proprietors before t825 were foreign-born—English, Dutch, Germans and Bohemians ; few of them, however, had received technical training or had been con nected with glass manufacture in Europe. Glass-making in America was entered into for the primary purpose of assisting in the indus trial growth and independence of the country. With the predomi nance of trained foreign-born workmen, the production took on the methods of mixing and manipulation which were practised by the gaffers, teazers and blowers in their former English, Dutch, Ger man and Bohemian houses. Thus it is not surprising to find a European prototype for nearly every piece of glass made in America during the first 200 years of her activities in this field. In structural forms and decorative motifs America imitated and assimilated. It was not until the coming of mechanical inventions that American types originated. To make attribution of i8th century glass more precarious, no designs, pattern books, moulds or mould models have survived.

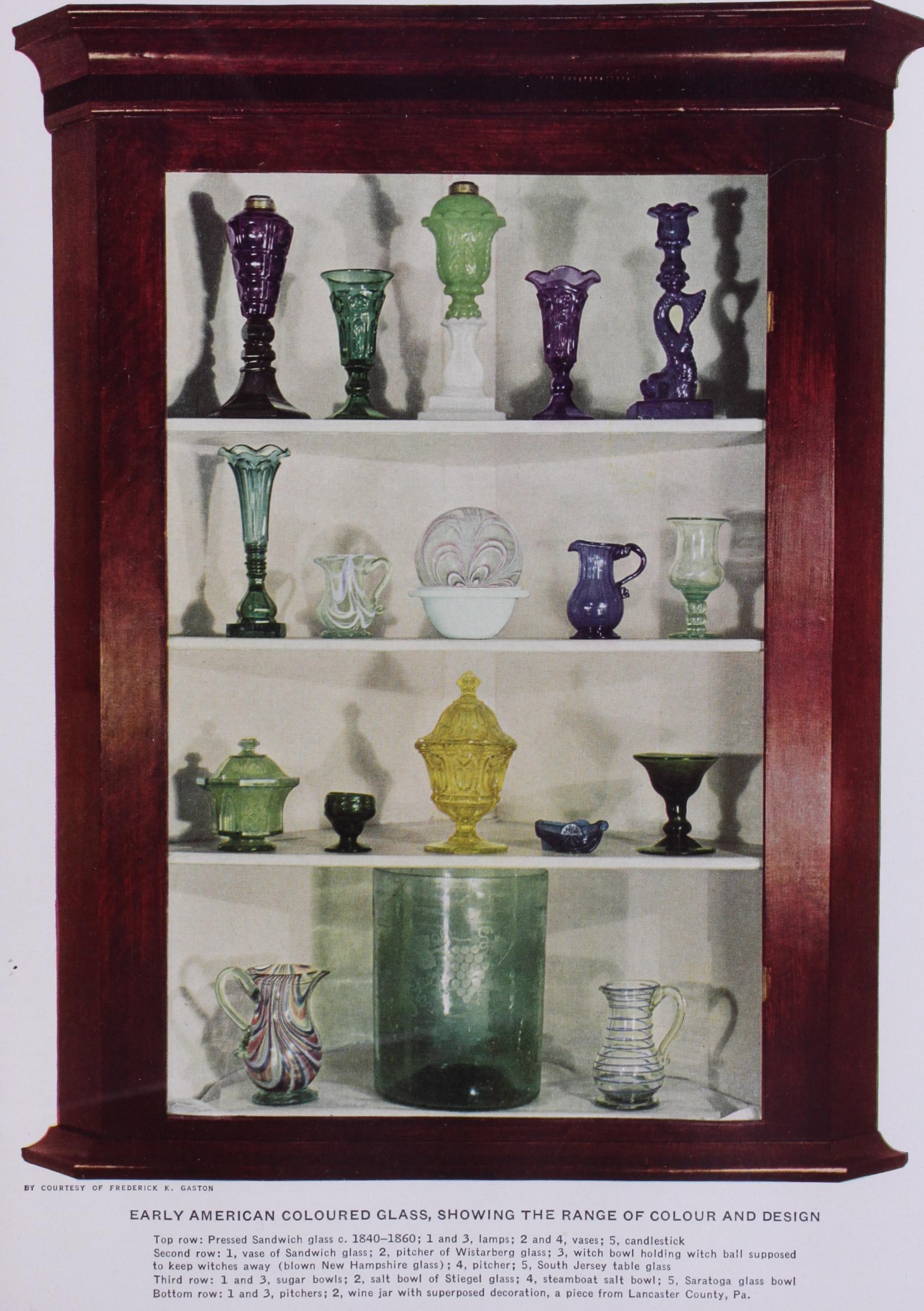

Caspar Wistar, who emigrated to Philadelphia from Germany, sent to Belgium for four glass workers in 1739. He erected a small furnace in South Jersey where window and bottle glass and chemical apparatus were blown. Upon Caspar's death in 1752 his son Richard took over the plant, enlarged its capacity, and carried on the work until 1781. The majority of the surviving authenticated examples are termed "off-hand" blown glass, i.e., pieces which the workmen fashioned for their friends or families apart from the regular production. The blowers often added a bit of colouring matter to the last run of glass in the pot, then exercised their greatest skill in fashioning these useful and orna mental objects. This off-hand blown glass forms the preponder ance of examples in the American collections until the advent of the historical blown and moulded flask and the invention of the mechanical pressing-machine.

Contemporary with the Wistar works, the Bamper-Bayard undertaking in New York and at New Windsor, up the Hudson, doubtless made the same kinds of glass and employed similar styles in the fashioning of the hand-manipulated household com modities. What we term the "South Jersey technique" was prob ably practised in a limited way by all of these blowers. It was not until the beginning of the 19th century that it flowered forth in several separate sections of the expanding country.

South Jersey types of glass are sturdy, substantial, capacious, bold of execution, yet well-balanced and graceful. There is a delicacy of curve in the handle and an artistry in the crimping of foot. Although a piece may combine plastically applied threads about the neck, superimposed decoration around the body, crimped handle and foot, it does not appear top-heavy, or over-elaborated. The principal methods of decoration are as follows:—( I) Super imposed decoration : After the piece had been fashioned, the lower portion of it was dipped into molten metal of the same colour, and while still plastic, the upper part of this second layer was tooled, or drawn out by pincers into wave-like, lily-pad or similar flowing ornamentation. Bowls, pitchers and vases were frequently thus treated. (2) Plastically applied threads of molten glass were wound around the necks of pieces, about the dome of a sugar-bowl, and occasionally around the body of a pitcher. These threads were often of contrasting colour to the piece itself. (3) Crimpings or indentations were applied to the still plastic finials, handle ends and feet of many examples. A little revolving wheel attached to a wooden handle was probably used for this purpose. (4) Blobs, prunts or seals of plastic glass were applied to the formed articles. Such ornamentation is frequently found in bi colour and tri-colour effects. This type is rare. (5) Striated or whorled bicolour and tri-colour combinations both in transparent colourings and in transparent and opaque glass were used by the latter-day houses. These alternating colour loopings, like their Venetian prototypes, produced a bizarre but beautiful effect.

The province of Massachusetts witnessed an undertaking from 1748 to 1757 which was fostered by Joseph Crellins from Fran conia and taken over by Joseph Palmer from Devonshire, Eng land. Situated near Quincy-Braintree, the place was called Ger mantown, the operatives being Palatinates. This glass works, in combination with other industrial endeavours, was one of the first localized general manufacturing attempts in the Colonies. The buildings were struck by lightning and burned down, and almost nothing is known about the production.

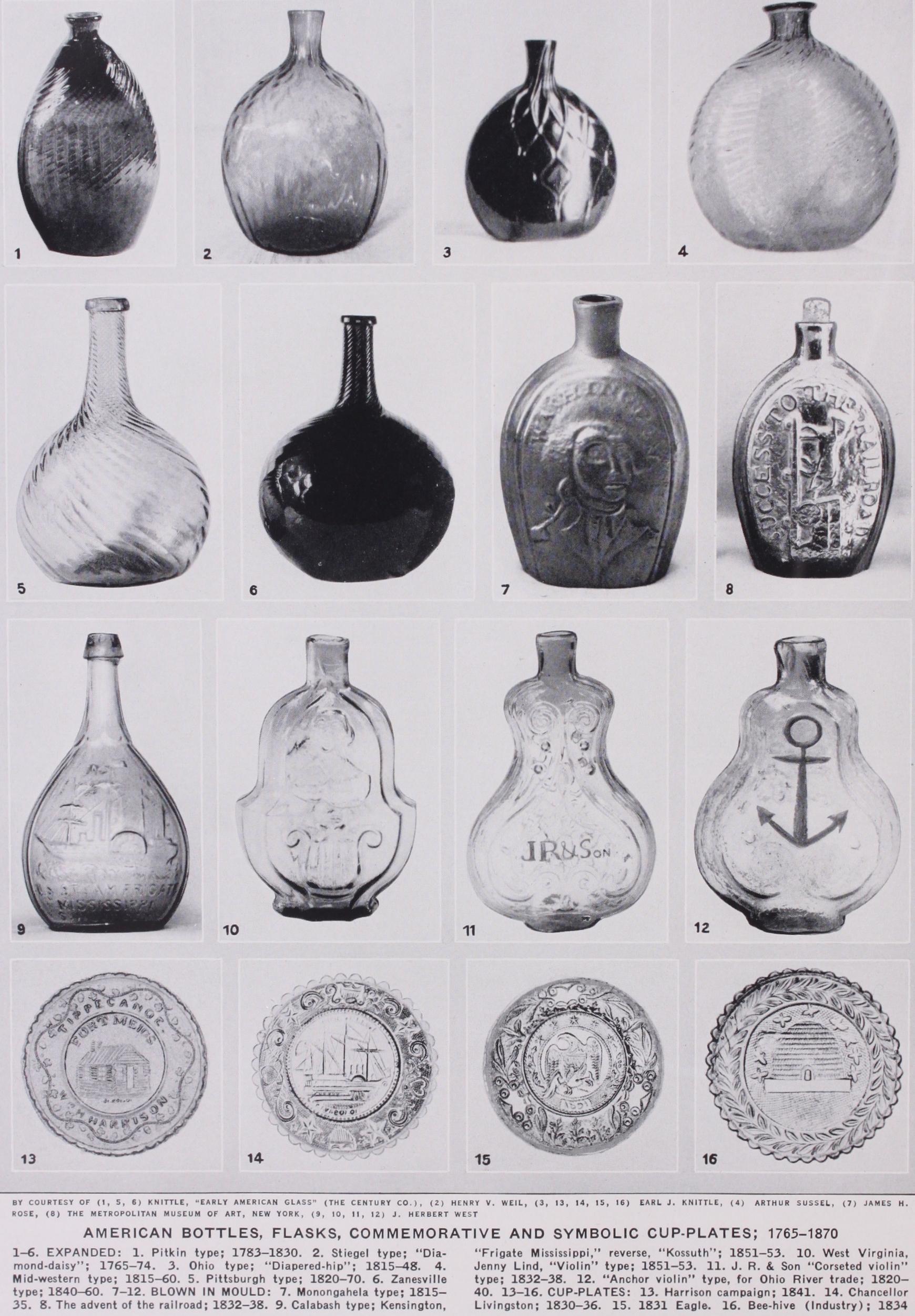

The Pitkin glass works, Connecticut, built 1783, was probably the first native plant to utilize "half-post" or double-dipped Ger man method of bottle blowing. These perpendicularly, closely ribbed and fluted flasks, later copied by the Keene works (N.H.), have become one of the outstanding types in the collectors' cata logue. The quality of the metal, and the green and amber colour ings found in the Pitkins are above the average. A limited number of clear white glass flasks blown in the same manner were made at some of the later mid-western houses. The bottle, embodying every method of manipulation, and every technique practised in America, is the outstanding glass product, holding the same rela tive position in America as that of the drinking glass in England.

The most beautiful glass ever blown in America was made in Mannheim, Lancaster county, Pa., by Henry William Stiegel who was born in Germany in 1729 and emigrated to the New World in 175o. Although he is frequently called "Baron" Stiegel, this title is erroneous, for he held no patent to nobility. He needed none. After small initial efforts at Elizabeth Fur nace, Stiegel believed that the time was economically ripe for a pretentious glass-making un dertaking in the provinces, that the tide of imports might be checked, taxation reduced and home industries developed. Tak ing the advice of patriotic Ameri cans, he purchased a one-third interest in a tract of land near Elizabeth Furnace, calling it Mannheim, and then proceeded to erect a good-sized glass-house and other appurtenances. Stiegel then departed for Europe where he learned some of the finer points of glass-making and hired trained operatives from Bristol, Venetian and Bavarian houses glass-cutters, engravers, etchers, gilders, workers in vitrifiable enamels and in the pattern-mould expanded technique. The lead flint metal mixers and the colour compounders brought their for mulae with them and the workmen brought their tools and prob ably some of their moulds. The first run of glass occurred at Mannheim in 1765.

This was probably the beginning of lead-flint glass-making in America. Everything augured success, but in two years the general depression preceding the Revolution, coupled with the increasing personal extravagances of Stiegel, gradually led to complete financial failure. Unmindful of the signs of the times, he erected a larger furnace in 1769. The last firing occurred in 1774. The name Stiegel, as applied to American glass, has unfortunately, like that of Wistarburg and Sandwich, become almost generic. Quan tities of glass, old and new, native and foreign, good and bad, are thoughtlessly or deliberately called by these names. Fine old blown coloured glass from Bristol, English-Irish cut-glass wines and decanters, Spanish, Dutch and German etched and engraved tumblers, flips and other articles, Rhenish enamelled cannisters and jugs, Venetian bottles, and the somewhat later American mid western specimens are unhesitatingly called Stiegel. Modern imi tations add to the confusion. Attribution and authentication of surviving pieces requires time, patience and caution.

The most outstanding types of glass made by Stiegel are as follows : (1) Plain surfaced blown and hand-manipulated ware. (2) Expanded types blown into part-sized pattern-moulds. (3 ) Panelled or fluted types, blown into full sized moulds. (The above groups are found in remarkably beautiful colourings, such as cobalt, emerald, amethyst and yellow.) (4) The use of vitrifiable enamels upon a clear white or a blue surface. (5) Cut, etched or engraved methods of ornamentation. (6) Gilded ornamentation, usually in combination with No. 5.

The greatest exodus of glass-workers from Europe to America occurred in 1784 when 82 operatives left the Bremen manufactory, Germany, and under the leadership of John Frederick Amelung established a communal industry near the town of Frederick, Md. Although exceptionally well financed, the enterprise soon collapsed.

Amelung made window, bottle and flint glass, yet few authenti cated pieces have been identified. The Metropolitan Museum of Art owns the most remarkable example, a marked and engraved covered presentation goblet on a bulbous baluster stem. After the abandonment of the New Bremen glass works, the blowers either established or found employment in the plants at Baltimore, Md., or in trans-Alleghany houses such as the New Geneva and the Pittsburgh, Pa., plants, the Wellsburg, Va. (now W.Va.), and the early Ohio furnaces. In 1 797 Major Isaac Craig discovered coal in a hill-side along the Monongahela river at Pittsburgh. This marked the beginning of glass-making across the Appalachian range of mountains. Anthracite and bituminous coal gradually supplanted wood as fuel for the glass-house furnaces. The erec tion by Craig and James O'Hara of an eight-pot window and bottle-glass house adjacent to this first coal bank was the beginning of the great Pittsburgh glass industry.

In the years following the Declaration of Independence until 1825, local and national troubles, sporadic wars, political agita tions, land-bubbles, panics, high transportation rates, and inebriate and nomadic tendencies of the workmen handicapped the progress of native glass-making. Long credits and poor collections affected economic stability, yet a constantly increasing population de manded glass for many purposes. The glass pressing-machine was invented in 1827, and in this momentous decade occurred the imprint of national heroes and historical objects upon whiskey flasks and cup-plates. The first historical flask was probably de signed by Thomas Stebbins of Coventry, Conn., or by Frederick Lorenz, who purchased the O'Hara works in 1819.

Numerous attempts at window and bottle-glass manufacture were made in upper New York State, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts and New Jersey from i800 to 184o, the off-hand blown examples from the Redwood, Redford, Salisbury, Saratoga, Stoddard, Glassboro and other houses generally manifesting the South Jersey technique. There were at least 25o glass-houses in America prior to 18; o.

Two Englishmen, Robert Towars and James Leacock, built a small bottle-glass furnace in Philadelphia in the Kensington dis trict. After passing through various ownerships, it was purchased and enlarged by the picturesque, self-styled "Dr." Dyott who established the patent medicine business upon a firm foundation in the United States. Dyott manufactured the containers at this furnace, and concocted the contents elsewhere. That he impressed his name, or that of Kensington, on so many of the bottles is a boon to the present-day collector. The two leading table-ware and flint-glass manufactories in Massachusetts were the New England Glass Company, of Cambridge, established in 1815, and the Boston and Sandwich Glass Company incorporated in 1825. Prior to 1818 none of the manufacturers could solve the secret of compounding red-lead or litharge, which prevented America from making crystal glass or lead flint which could be cut in the English manner. Deming Jarves, then an owner of the Cambridge works, built a set of furnaces for experimentation in the com pounding of litharge, his first attempt meeting with success. For years Jarves held the monopoly of the red-lead business in Amer ica. In 1827 Enoch Robinson, of the Cambridge industry, invented the first crude pressing machine, which was almost immediately improved by Jarves, now a part owner of the Sandwich plant. By 1838 the invention was perfected and pressed-glass became popu larized, although it did not become a household commodity until about 1845. America was now sending these machines to all the glass centres of the world. Both these firms made lovely blown glass before and after the installation of the mechanical pressers, their insufflated types evidencing an infinite variety of geometrical, arched and baroque patterns. English and French designs were copied by the mould model designers in the making of this contact mould ware, the mould itself always being full sized, and gen erally three sectional, although it was occasionally of four parts. No comprehensive name for this kind of glass has yet been de vised. The metal is usually very thin, and the glass is frequently iridescent. It has been found in many colours. Other houses, such as Pitkin, Stoddard, Amelung, Zanesville, Kent and Greens boro, also manufactured this type of glass.

The Cambridge and Sandwich industries manufactured large quantities of glass for over so years, the former attaining fame for their cut flint ware in the Waterford manner, for their pressed glass and their fine opalescent examples. Many foreign designers were engaged by both houses, the Sandwich works making fine lace-like patterns on their pressed ware, the metal of which was of a superior quality. Every shade and range of colouring known to glass-making was employed, the coloured opaque glass becoming as deservingly famous as the blown and pressed candlesticks and lamps and their overlay manipulation. Sandwich also made a great variety of salts and cup-plates. In Pittsburgh two contem porary flint-glass works, Bakewell, Page and Bakewell, and James B. Lyon, turned out both blown and pressed ware of fine quality. Bakewell's probably produced more meritorious cut, etched, en graved and gilded glass than any American factory. Lyon, ac knowledged by his contemporaries as the finest glass-maker of his day, was the first manufacturer to adopt pressed-glass as a main line instead of blown glass. He was awarded many honours and medals in his field of endeavour. Fisher and Gillerland of New York city, the McKees and James Bryce of Pittsburgh and several other mid-western houses made an enormous amount of very good glass which has been incorrectly attributed to Sandwich. Patterns could not be protected, mould-makers were migratory, and popular designs such as the bellflower were turned out by all these manufacturers.

The leading Zanesville, O., glass-works was granted an oper ating privilege in 1815. This bottle-house is credited with the introduction of the long-necked, bulbous-bodied, swirled and ex panded bottles found in a variety of colours. What is now called the mid-western technique, an adaptation and a frequent combina tion of the Stiegel and the South Jersey methods, emanated from Zanesville and other glass-works in this territory. Many splendid specimens of off-hand blown glass have come from these houses. The scroll and violin types of bottles probably originated at Wells burg, W.Va., the Louisville, Ky., plant adopting the violin shape as a main line of production. These bottles are found in a greater variety of sizes and colourings than any others made in America. The invention of the snap-case, used for holding the bottom of the bottle while in the making, occurred in 1857. This eliminated the rough mark of the pontil rod. In 1858 the discovery of petroleum created a thriving business in glass lamps and chimneys, the later introduction of artificial gas as an illuminant ruining many glass works.

At the close of the Civil War, glass-making in America be came modernized. Many of the 'older workers were crippled or killed, causing the hand-manipulated methods to cease. The Barns Hobbs-Brockunier flint glass works at Martins Ferry, O., gave the industry three important innovations : (r.) the Leighton process— the use of soda-lime in the batch to supplant litharge, which greatly reduced the cost of production, but robbed such pressed glass of its resonant quality ; (2) the use of benzine in the glory hole or polishing furnace; (3) the mechanical application of cold air to the moulds for the purpose of chilling them. The discovery of natural gas in mid-western districts led to increased glass pro duction and ultimately to an enormous mass-tonnage in Pennsyl vania, Ohio, West Virginia, Indiana and Oklahoma.

American forms and ornamentations of glass-ware became de cadent in the era of poor taste in all the arts and crafts between 186o and 189o. Much glass was manufactured in that period which is not worth preservation. In 1870 America was making : (1) plate-glass, including rough, ribbed or polished plate and rolled cathedral plate; (2) window-glass, including cylinder and sheet ; (3) table-glass, including flint, lead or lime glass, both blown and pressed, lamp chimneys and flint druggists' and chemists' ware; (4) green glass, including green, black, amber and other bottle glass, fruit-jars, carboys, demijohns and other hollow ware and green druggists' ware.

Cut glass attained a high degree of excellence and a great vogue in America around 189o, the Libbey firm of Toledo, 0., becoming world renowned for their output. John LaFarge about this time did more than any one man "to replace glass painting in the sphere of art." The leading art glass manufactured in the United States was evolved in this period and is known as the Tiffany favrile.

Modern Tendencies.

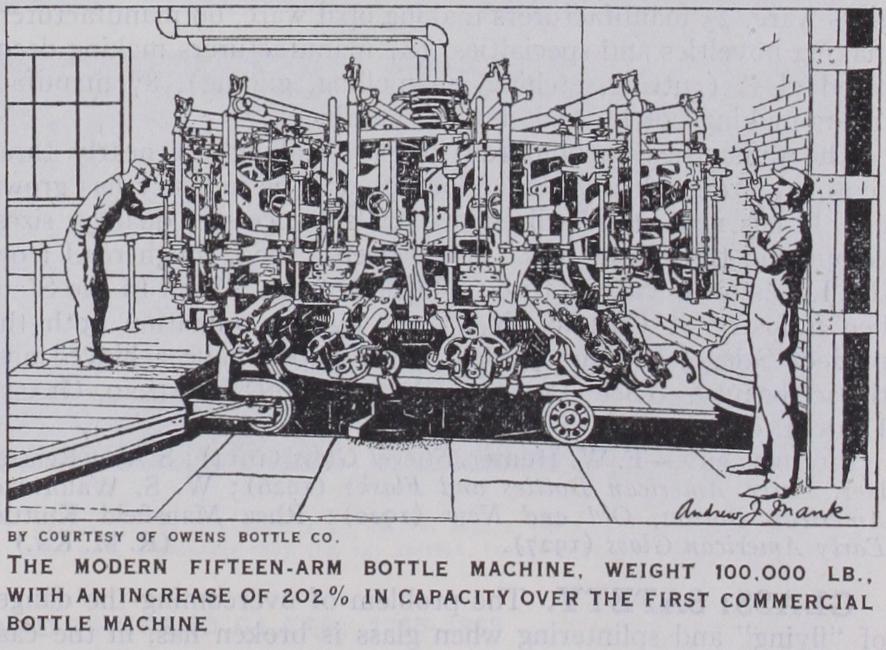

The present tendencies (1928) among table glass and art glass manufacturers favour reproductions of early American blown and pressed glass, the earlier Venetian blown glass, the Waterford cut-glass, engraved Spanish glass, Bo hemian overlay glass, pressed patterns from Nancy and Baccarat, recent copies of Lalique and European modernistic forms. Intri cate machinery in connection with the industry has been constantly invented or improved upon since 1895, including the bottle ma chine, an automatic instead of a semi-automatic piece of mecha nism. Its first conception occurred in 1899, the inventor being Michael J. Owens. Beds of better grade silica for glass-making were discovered about 1900, causing an increase in the resistance of glass to corrosion and decay, but also an increase in its resist ance to melting and fusion. American manufacturers achieved the art of red signal glass-making in the solid, replacing the plating, casting or flashing process.In 1927 the United States had 54 manufacturers making table ware and home products, 44 manufacturers making blown or pressed tumblers or stem-ware, 39 manufacturers making coloured glass-ware, 23 manufacturers making opal ware, 69 manufacturers making novelties and specialties, i o i manufacturers making deco rated glass (cutting, etching, enamelling, gilding), 87 manufac turers making bottles and similar containers.

The difficulties encountered in glass-making for nearly three centuries are gradually being eliminated. The industry has grown up. It has now standardized materials, processes, quality, sizes, colour and trade practices. It has been a long, rough road from the Jamestown, Va., venture to Triplex, from Stiegel to the Steu ben industry at Corning, N.Y., yet by determination both the pioneer Stiegel and the present-day Steuben have achieved aes thetic beauty. (See INTERIOR DECORATION; STAINED GLASS; DRINKING VESSELS.) BIBLIOGRAPHY.-F. W. Hunter, Stiegel Glass (1914) ; S. Van RensseBibliography.-F. W. Hunter, Stiegel Glass (1914) ; S. Van Rensse- laer, Early American Bottles and Flasks (1926) ; W. S. Walbridge, American Bottles, Old and New (1920 ; Rhea Mansfield Knittle, Early American Glass (1927). (R. M. KN.)