Anatomy

ANATOMY : Respiratory Organs) and the estuaries of most great rivers contain certain forms which can endure daily and sea sonal changes of salinity, etc.

Similarly, among terrestrial and fresh water gastropods there are forms which are of wide toler ance and live indifferently in water or on land, either being structurally adapted, as in the case of the lung snail (Ampul laria) which lives in swamps, and has both a gill and a lung, or having a more or less gen eralized adaptability (certain species of Limnea). Hesse records that an exclusively terrestrial Pulmonate (Laurin cylindracea) has taken to living in springs in certain parts of Germany.

The majority of the Streptoneura are marine, but the Helicinidae among the Rhipidoglossa, the Cyclophoridae and Cyclostomatidae among the Taenioglossa have become terrestrial. The members of the genus Theodoxis (Neritina) are the only Rhipidoglossa that have invaded fresh water; but many groups of Taenioglossa inhabit the latter, viz., the Viviparidae, Melaniidae, Ampullariidae, Valvatidae, etc. The Stenoglossa are exclusively marine. Among the Euthyneura the Opisthobranchia are likewise a marine group.

The Pulmonata are mainly terrestrial, though certain large fam ilies (Planorbidae, Limnaeidae) live in fresh water, and a few (Amphibola, Siphonaria) are marine or littoral (Auriculidae).

The horizontal distribution of marine gastropods can only be treated very summarily here. It is sufficient to say that certain main distributional areas can be recognized which have their peculiar and characteristic faunas, the latter being composed of genera and species which are either restricted to those areas or are more frequently found there than elsewhere. For ex ample, in the region between Delagoa Bay and Cape Agulhas, which we may regard as the South African marine province, are found the following genera which occur nowhere else: Abys soclirysos, Jeireysiopsis, Alcira, Cynisca, Neptuneopsis and Alex andria. Furthermore, Bulla Terebra, Ancilla, Patella, Mitra and Turritella, though they occur in other parts of the world, are in this region very richly repre sented in species, so that South Africa may rightly be considered the metropolis of these genera.

The range of individual species is, as in other groups, limited to special areas; but ambiguity as to the precise limits of species makes it difficult to define these areas with exactness in any par ticular case (see SPECIES), while our ignorance as to the oppor tunities for dispersal and of the physiological constitution and reactions of individual species usually make it impossible to state to what extent the range of species is the expression of a definite constitutional peculiarity.

The vertical distribution of marine gastropoda shows a broad grouping of genera according to the preference of special habitats. At the landward limit of marine condi tions and often beyond the high-water mark of spring tides are found semi terrestrial forms, such as the Littorinidae. Well up to high-water mark forms like the marine Pulmonate Siphonaria are found, while the limpets (Patellidae) range up to the same level. Between tide marks (lit toral zone) are found the Fissurellidae, ormers (Haliotis) Oncidium, the top shells (Turbo) and dog whelks (Purpura), as well as those which ascend further beyond the reach of maritime conditions, such as the Littorinidae. Farther down the strand in the shallow water of the Laminarian zone occur a great variety of forms, no tably the Nudibranchia. Adaptation to a particular kind of bottom is here of great importance. Burrowing forms, like Sinum, Natica, Cypraea and Bulla are more fre quently found in sand, while the less ac tive creeping forms keep to fronds of Laminaria and other seaweeds, the sur face of algae, smooth rocks, and the like. Vermetus, which is a sessile gastropod with an uncoiled shell, forms irregular masses on rock and coral. Eulima and other par asitic forms are found on the external surface or in the body cavity of star-fishes and also in Holothuria. Magilus and Coralliophila burrow into corals. From the shallow waters downwards the gas tropod fauna becomes more sparse. The late W. H. Dall, in his report on the marine gastropoda, obtained by the "Blake" in the gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean sea, gives the following num bers of shallow and deep-water forms: Littoral species, 28o, species found down to the edge of the continental shelf (about too fathoms) 222; deep water species, 83. Among typical abyssal genera are Mangilia, Margarita and Pleurotoma. The greatest depth from which a gastropod has been so far taken is fathoms (U.S.S. "Albatross" off the coast of Peru).

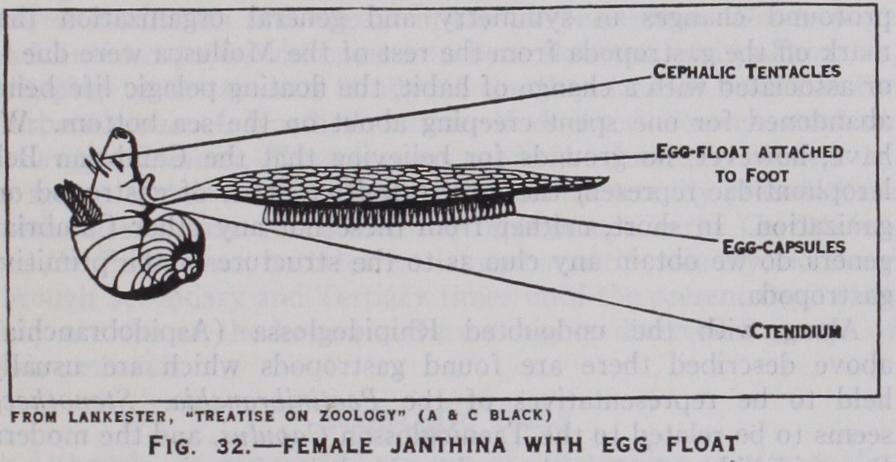

The forms which have so far been considered are those which in adult life live permanently on the sea bottom. The larvae of very many of these are floating organisms which form part of the marine plankton until they metamorphose into the adult condition. There are, however, three groups and some isolated genera of gastropoda which permanently live floating off the bottom. These are the Heteropoda, an interesting group of Taenioglossa, some of which are curious, highly modified creatures, and the Thecosomata and Gymnosomata. The last two groups, which are sometimes erroneously united into a single group called Pteropoda, form a very large part of the minute plankton of all seas. Over 4,00o specimens of Limacina helicina were obtained by the "Terra Nova" in a single haul in McMurdo Sound (antarctic). The purple snail lanthina, which secretes a gelatinous float for its eggs, and the nudibranchs Phyllirrhoe, Glaucus and Scyllaea, are similarly pelagic, while several tectibranchs such as Aplysia and Tethys are modified for swimming, though they seem to keep near the bottom.

Freshwater gastropoda are omnipresent. They are found in high tarns in the Hima layas, where Limnea hookeri has been taken at a height of over i 8,000f t. above sea level. Aplecta hypnorum reaches as far north as 73° N. in the Taimyr peninsula. The most characteristic and widely spread freshwater gastropoda are members of the Viviparidae, Melaniidae, Theodoxis, Limnea and Planorbis. They occupy a great variety of habitats—not only rivers, lakes, streams and smaller stretches of water, but also hot springs, torrents, the "trickles" down the faces of cliffs, and marshes. They also invade cattle-troughs, irrigation ditches, water mains and cisterns. As in the case of marine gastropoda, there is some uncertainty as to the precise range and exact habitat of individual species, though in particular areas the habitat of certain species is fairly well defined. Vivipara vivipara, the common river snail of the British Isles, prefers slowly-flowing rivers and canals; Valvata macrostoma is usually found in marshes and ditches. Pilsbry and Bequaert record the fact that Limnea natalensis undussomae, Physopsis a f ricana, and certain species of Planorbis prefer open shallow pools of small size. Certain great river systems are occupied by characteristic genera. For example, species of Cleopatra and Lanistes are peculiar to the Nile drainage area. Other genera are practically cosmopolitan, such as Unio, Vivipara and Limnea.

The gastropoda which live on land are not so tolerant of ex ternal conditions as are certain other groups of terrestrial inverte brates. In Spitsbergen, which on account of divers adverse fac tors (low winter temperature, etc.) does not sustain a very large and varied animal population, there are no land Mollusca at all, though there are a number of Collembola, Diptera, spiders, mites and other invertebrates.

Extremes of temperature do not as a rule limit the distribution of land gastropoda. Lack of moisture and of lime in the soil on which they live appear to be the most important factors in pre venting their spread. In tropical countries lack of shade and suitable places for concealment from excessive heat and light act in a similar way. As a rule they are not found plentifully on "acid" soils. Alkins and Lebour found that of 27 species, 20 were found on rather alkaline soils (pH7•o), 14 tolerated rather more alkaline soils (pH8.o), while only four were found on acid soil (pH5). They are likewise poorly represented in deserts and other dry habitats, although they are not necessarily absent from the latter if there are opportunities for burrowing and a plentiful dew-fall.

Apart from these limitations the terrestrial gastropoda are al most world-wide in distribution. A slug Anadenus is found at i 7,000ft. in the Himalayas, and Chronos sublirnis was taken at over i 6,000f t. on Mt. Carstenz in New Guinea. Land snails and slugs are found in well-vegetated areas, e.g., woodland, pastures, hedges and banks, jungle, among mosses and lichens and in more arid situations such as cliff faces, rocks and sand dunes. They burrow underground, climb trees and invade houses.

The means by which land gastropoda are dispersed act rather more slowly than those by which marine and freshwater forms are carried about. As a result, land snails and slugs are more localized in their distribution. Extreme cases of such restricted distribution are seen among the Achatinellidae (tree snails) of the Sandwich Islands and the Partulas of Tahiti. Many species of these groups are restricted to single valleys or ridges, and well marked mutational forms are even said to be restricted to a single tree or group of trees.

On the other hand, given suitable conditions, dispersal may be to a certain degree facilitated by their habits and constitution. Bartsch has pointed out that the Cerions of the Florida Keys, etc., which can live for four days in sea-water and have the habit of fixing themselves to dead wood during estivation, have probably been transported from island to island after hurricanes which have washed away such timber from the low-lying coastal regions which the Cerions inhabit. The chief continental areas of the world are each characterized by a number of peculiar families and genera, and certain deductions as to former land-connections between such areas may be made. Thus the Achatinidae, Dor casiinae, Limicolaria, Burtoa, etc., are exclusively found in Africa and the Bulimulidae, Drymaeus and Borus, in South America. Among the land Mollusca of South America, however, are repre sentatives of the Stenogyridae, a family characteristic of African fauna, and conversely there are Bulimulus-like genera in Africa.

Habits, etc.—The greater number of gastropoda are passive animals of relatively small size and limited powers of locomotion. Usually increase of activity is associated with the carnivorous habit. Their inertia and lack of mobility are compensated by the shell, their more or less obscure appearance and secretive habits, which are their chief defences against enemies. Among marine forms the great power of adhesion manifested by the foot prevents them from being washed away to unfavourable ground. On land the habits of burrowing and entering crevices, of estivation and hibernation are safeguards against climatic excess. Protection against drought is of great importance for animals which require much water. The shelled terrestrial forms are protected against desiccation, and in addition many have the faculty of secreting a covering to the aperture of the shell of ter they have retired into the latter. The naked forms die very quickly if exposed to very dry air or strong sunlight. Both shelled and naked forms tend to secrete themselves in the daytime and to emerge in the evening or during rainy spells.

Apart from the dependence upon certain necessary external conditions gastropoda seem to be adaptable animals and pe culiarly tenacious of life. There are well-authenticated records of land snails which have lived for years without food.

Marine and terrestrial gastropoda have to contend with other hostile forces besides the physical factors of their environment. Marine Mollusca are preyed upon by a variety of enemies. As eggs and larvae they are eaten by very many vertebrate and in vertebrate animals. Fish and sea-birds feed on them in the adult state and whales consume large quantities of the planktonic forms. Birds, carnivorous beetles and small mammals such as rats and mice, take a heavy toll of land snails. Ducks, geese and water beetles feed on pond and river snails.

The gastropoda are vegetable eaters, carnivores or live on organic debris of all kinds. Most Aspidobranchia and glossa feed on plants, the marine forms browsing on algae. Natica, the lariidae, and the Heteropoda are, however, carnivorous. Natica preys on branchs, through the shells of which it bores by means of an acid secretion. tain F. Davis found that the clam Spisulla elliptica is persistently preyed upon by Natica alderi on the Dogger Bank, about 88% of the clams taken on certain hauls having their shells bored by their enemy. The sessile Taenioglossa, like Vermetus, are plankton-feeders. The Stenoglossa are mainly carnivorous and prey upon other molluscs, or else they feed on•carrion. Among the Opisthobranchia the Eolids feed on hydroids, the stinging cells (nematocysts) of which are retained and stored in the dorsal papillae, from which they are discharged when the animal is attacked. The majority of the land Pulmonata feed on green plants, fungi, lichens or table debris. The snail-slug (Testacella) feeds on earth-worms, and Glandina, Oleacina and the Streptaxidae are similarly carnivorous. Commensalism is not of such frequent occurrence among gastropoda as it is among Lamellibranchia. A certain number of Taenioglossa are ectoparasitic (Stili f er, Thyca, etc.), and endo parasitic (Entoconcha, Entocolax) upon echinoderms. The only other animal that has so far been recorded as being the host of a gastropod is the stomatopod crustacean Gonodactylus chiraja, which harbours Epistethe gonodactyli. In their turn gastropods serve as hosts for parasites of various kinds. Certain trematode worms pass part of their life-cycle in marine and freshwater gastropods, and in two cases the association is of serious conse quence to man. The effect of these parasites on the snail is sometimes disastrous. The author of this article found a high percentage of a small gastropod Paludestrina ventrosa castrated by a trematode which had invaded the reproductive organs of its host. Infection by such parasites is probably high when the parasite passes the rest of its life-cycle in a vertebrate host which preys on the gastropod, as in the case of sea-birds which feed on small water snails in tidal ditches. Certain dipterous flies are parasitic on land snails and several kinds of mites are found on the latter, though it is uncertain if they are actually parasitic.

The gastropoda are protected, as has been stated above, from the attacks of enemies by passive means (their shell and retiring habits). The shell, however, is not always an adequate safeguard from assault. Carnivorous beetles thrust their heads into the aperture and drag the inmate out. Boettger has produced some very interesting and suggestive observations on the relation be tween attacks of this sort and the development of projections from the sides of the shell-aperture in certain land snails (Otala) which are attacked by carabid beetles. Whether the colour-pattern and sculpture of the shell, which is often very elaborate, are of any protective value is uncertain at present. Observations upon the destruction of the common hedge snails (Cepea) seem to show that birds do not discriminate between the banded and the un pod shells; but unfortunately we know practically nothing about the internal structure of extinct members of the class. The status of many interesting and important fossils cannot therefore be satisfactorily discussed in terms of the classification usually employed.

The earliest undoubted gastropod remains found in the Lower Cambrian (Olenellus) beds include spirally-coiled shells (Raph istoma) and others which are cup-shaped (Scenella, Palaeacmea). The latter are usually treated as representatives of the Docoglossa (limpets) which, owing to the presence of a spiral protoconch (embry onic whorl), must be considered as de scended from spiral ancestors. In some what later Cambrian horizons are found undoubted gastropod shells of a plano spiral (nautiloid) shape (Cyrtolites, Bel lerophon). These were actually regarded as nautiloids by Deshayes and placed by him in the Cephalopoda. They are now held to be gastropods and have been com pared with the pelagic Taenioglossan At lanta. The slit at the edge of the shell aperture comparable with that found in the rhipidoglossate Pleurotomaria, a genus which appeared in the Silurian (possibly in the Cambrian), justifies the inclusion of Bellerophon among the Rhipidoglossa rather than the Taenio glossa. Nevertheless the similarity of their shell to that of the pelagic Atlanta suggests that they were of a swimming or float ing habit and gives some support to the theory of Naef that the profound changes in symmetry and general organization that mark off the gastropoda from the rest of the Mollusca were due to or associated with a change of habit, the floating pelagic life being abandoned for one spent creeping about on the sea bottom. We have, however, no grounds for believing that the Cambrian Bel lerophontidae represent the most primitive grade of gastropod or ganization. In short, neither from these nor any other Cambrian genera do we obtain any clue as to the structure of the primitive gastropoda.

Along with the undoubted Rhipidoglossa (Aspidobranchia) above described there are found gastropods which are usually held to be representatives of the Pectinibranchia. Stenotheca seems to be related to the Taenioglossan Capulus, and the modern Pyramidellidae are traced to other Cambrian forms.

The Streptoneura are thus well represented in the oldest fos siliferous rocks. In lower and upper Silurian times they increased and many families still flourishing appeared at that epoch, e.g., the banded varieties of C. hortensis and C. nemoralis. Few positive instances of protective or warning coloration are known, as the habits and enemies of the animals concerned are so imperfectly known. Various species of Coclilicella certainly resemble the seed-pods of the plant on which they mainly feed, and certain Clausilias are sufficiently like leaf-buds; but it is difficult to de cide if these resemblances are more than fortuitous. Sundry marine forms which feed on holothurians and tunicates resemble these animals in colour; but again the protective value of the resemblance is uncertain.

Scalaridae, the Capulidae and Turbinidae. Many groups of Rhipidoglossa now extinct reached their developmental climax in mid-Primary times. The Pleurotomariidae, represented at the present day by four very rare species, numbered several hundred species.

Undoubted Euthyneura do not appear until the Carboniferous, when tectibranchs like Acteon, etc., are found. With this fact in mind, it is necessary for us to consider briefly one of the most puzzling series of fossils that have been found in Primary rocks.

For a long time certain tubular shells resembling somewhat those of "Pteropods" have been known from Cambrian strata. They have variously been interpreted as thecosomatous pteropods, as cephalopods and tubicolous annelids. Broili (in the last edition of Zittel's Grundziige der Paldontologie) retains them in the gastropoda as an enigmatic class, the Conularida. In 1911 Wal cott, in describing the Cambrian fauna of the Burgess shales (British Columbia) figured a species of the genus Hyolithes, H. carinatus, in which are seen structures somewhat re sembling the fins of pteropods. It is not easy, however, to accept these structures as indicative of fins like those of thecoso matous pteropods, and as the shells of these forms are not in themselves suf ficient clue to the identity of the animals it is better to accept Broili's verdict.

Nevertheless, if these remains are subse quently proved to be those of pteropods, and if the hiatus in time between their appearance and that of the other Opistho branchia is not merely due to the imper fection of the geological data, then we shall be driven to one of the two very interesting conclusions. It will be necessary to assume either that the Thecosomata were developed directly from the primitive streptoneuran stock and are not from the Opisthobranchia, as is usually believed, or that the Cambrian Thecosomata have nothing to do with modern "Pteropoda," but represent an early essay in pteropod-like specialization.

The Pulmonata first appear in the Carboniferous. Dendropupa and Anthracopupa, which seem to be undoubted land pulmonates, referable to the modern family of the Pupidae, are found in the Carboniferous of North America. Undoubted Basommatophora (Auricula, Limnea, Planorbis) appear in the Jurassic; but it is by no means certain if the terrestrial Pulmonata actually preceded the fresh-water forms. Since their first appearance in the Carbonifer ous the Pulmonata, both terrestrial and aquatic, steadily increased through Secondary and Tertiary times until the present day, when they are one of the largest and most highly diversified groups of living animals.

Although the gastropods are not of outstanding service or dis service to man in any one respect they are of considerable im portance in a number of ways. Their chief value is perhaps as an article of diet ; for since the earliest stages in man's develop ment they have been used as food. In middle and late Paleolithic deposits in Europe, limpets, periwinkles and top shells occur. In certain "kitchen middens" of the Upper Paleolithic in the west of Scotland they occur in such profusion as to lead one to suppose that the people who formed these deposits lived prin cipally upon these molluscs. The natives of Tierra del Fuego, according to Tylor, used similarly to sub sist on various kinds of shellfish, and gas tropods of various kinds occur in their middens. At the present day H. Lang (quoted by Pilsbry) states that the Acha tinas (large land snails) "are a welcome addition to the food supply of most tribes" in the Belgian Congo, and that their shells "are seen lying on refuse heaps and along the rivers." Among European peoples whelks, periwinkles and ormers are largely consumed; 889 tons of whelks and 3,245 tons of periwinkles were delivered at Billingsgate market, London, in 1922. Though landsnails are only eaten in a few districts in Eng land they are largely used in France, where Helix pomatia (the Roman snail) is cultivated on escargotieres or snail farms.

As bait and as the food of edible fishes, birds and whales, gastropods are of substantial indirect value to man.

The shells of gastropoda have been put to a variety of uses by the different races of mankind. The mother-of-pearl obtained from large specimens of Turbo and Haliotis is imported into Europe for button-making, inlaying and sundry articles of virtu. Among native tribes shells are put to many uses. Those of Cypraea moneta (the money cowry) are used as currency in Africa and elsewhere, and other species of Cypraea are reserved as ornaments for kings and chieftains in the Pacific islands. The left-handed chank (Turbinella raga) is used in the ritual of the god Vishnu in India. Trumpets are still made from Triton shells in Africa and the East, just as they apparently were among the early inhabitants of the Mediterranean. The natives of Central Africa use the large shells of various species of Achatina as drinking-vessels and salt-containers.

The rock-whelk (Murex) is no longer fished in the Mediterra nean for the sake of the dye which was used in preparing "Tyrian" purple; but species of Fasciolara are still employed for obtaining dye by various native races.

Gastropoda are obnoxious to man in at least two important connections. Considerable damage is done to crops by slugs and land snails A small snail Zonitoides arboreus causes sugar-cane root disease in Louisiana. Marine gastropods are less obviously obnoxious to man, but one at least in the British Isles has proved itself a troublesome pest of oyster-beds. This is the American slipper limpet (Crepidula fornicata), which was accidentally in troduced many years ago and has since then multiplied excessively and overruns the oyster beds in south-east England. A more disastrous work is done by those freshwater gastropods which harbour parasites harmful and•even fatal to man and one of his more valuable domestic animals. (a) In the Middle East, in Japan, various parts of Africa and in South America and the West Indies, species of a trematode, Schistosorna (=Bilharzia) which cause bladder disease in man, pass part of their life cycle in various species of lsidora and Planorbis. A focus of this dis ease has been recently detected in Portugal, where Planorbis metidjensis is probably the intermediate host of the parasite. (b) The liver fluke (Distomum liepaticurn) passes part of its life in the water snail Limnea truncatula. Sheep grazing in flooded meadows or near streams become infected with the fluke, which causes "liver-rot." For the historical treatment of this subject see MOLLVSCA.