Applied Geophysics Geophysical Prospecting Geophysical Exploration

GEOPHYSICAL PROSPECTING (GEOPHYSICAL EXPLORATION, APPLIED GEOPHYSICS) is the ap plication of the principles of geophysics (q.v.) to the location of mineral deposits.

In various branches of geophysical science (geodesy, seismol ogy, terrestrial magnetism, etc.) a relation between the surface distribution of physical forces and the physical properties and disposition of major geologic features in the earth's crust had been observed at an early date. In geophysical prospecting, sim ilar observation methods as in geophysical science, are employed ; apparatus and methods are more sensitive and adapted to the determination of local geologic structure. Hence, geophysical prospecting may also be defined as the location of subsurface structure and mineral deposits by surface measurements of physi cal quantities. It is not to be confused with the divining-rod (q.v.) for which a sound scientific foundation has yet to be es tablished. Geophysical prospecting is applicable only if differ ences in physical properties exist between the sought geologic bodies and their surroundings, such as : Magnetic susceptibility, density, elasticity, electric conductivity, thermal conductivity, and radioactivity. If a specific commercial mineral does not pos sess these properties itself, it may often occur in mineralogic, stratigraphic, or structural association with other media which have such properties and can be located. This is known as in direct geophysical prospecting. An outstanding example is the indirect location of oil. With present technique, oil cannot be found directly ; geophysical oil exploration utilizes methods to locate geologic structures (anticlines, salt domes, faults) which are expected to be oil bearing.

(a) Review of Methods.

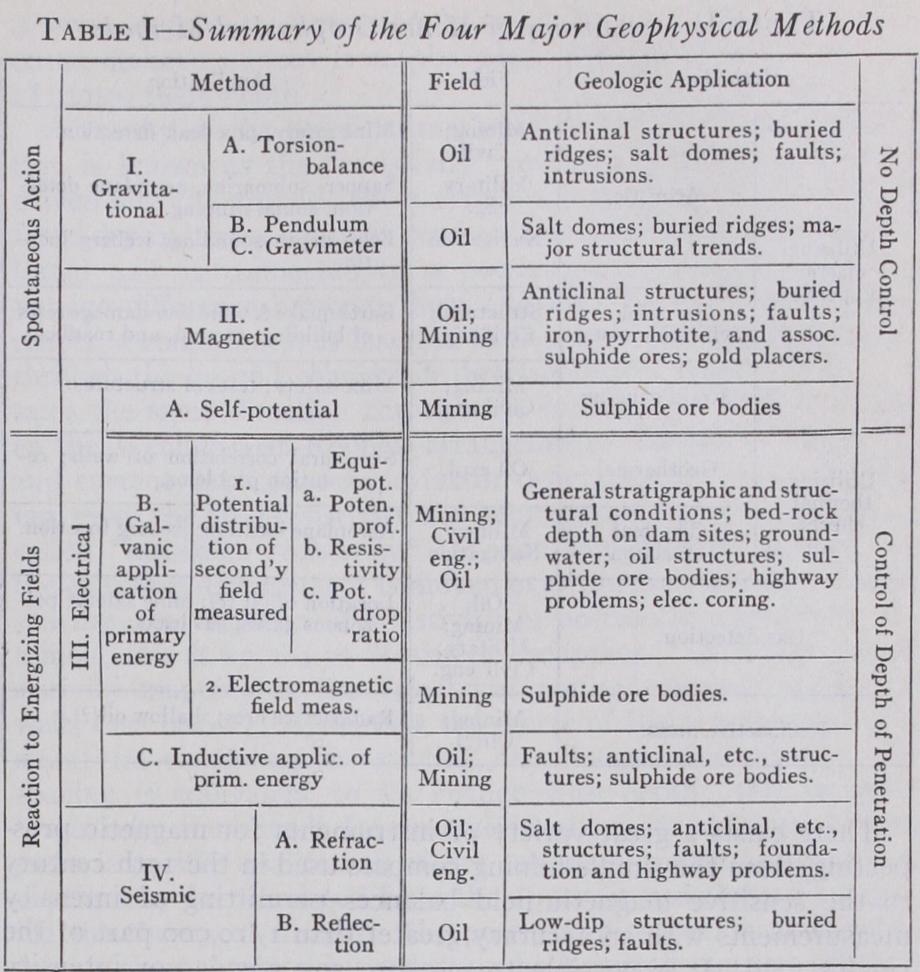

In accordance with the physical properties responsible for the effects of geologic bodies, the fol lowing methods may be distinguished in the order of properties enumerated above : Magnetic, gravitational, seismic, electrical, geothermal, and radioactive methods. In all these methods, cer tain physical effects are observed which must be interpreted in terms of geology. From the point of view of interpretation, geophysical methods fall into two major groups : (1) Methods without, and (2) methods with depth control. In the former, spontaneous effects are observed which represent the sum of the effects of all bodies within range ; it is possible that a small body at shallow depth exerts the same influence as a large body at greater depth. The gravitational, magnetic, and the self-potential methods (see Table I) of electrical prospecting exhibit this lack of depth control. Interpretation of results obtained by these methods is of an indirect nature : Geologically justifiable assump tions are made about the subsurface section, its effects are calcu lated, compared with the field findings, and modified until a rea sonable agreement between theoretical and field data is obtained. In the second group, effects of geologic bodies do not appear spontaneously but must be produced by transmitting (seismic or electric) energy through the ground; they thus appear as anomalies in seismic wave speed and electrical conductivity. As it is possible to regulate the depth of penetration by a suitable spacing of transmission and reception points, effects of shallow bodies can be separated from those of deep bodies; as a matter of fact, depths can usually be determined directly. Another advan tage of methods with depth control is that the physical proper ties of the formations traversed by the energy may be deduced.It is customary to distinguish a number of subdivisions within the major geophysical methods, depending on type of instruments used, quantities measured, or on method of energy supply and reception. Table I illustrates the major groups of geophysical methods together with their subdivisions and geologic applica tions. Details on each method with special reference to rock properties, instruments, and interpretation procedure are given in the following sections.

(b) Gravity Methods.

These methods are based upon the measurement of physical quantities related to the gravitational field which in turn are affected by differences in densities and disposition of geologic bodies beneath.The densities of a few minerals for which gravity prospecting has been done may be enumerated : Pyrite, ; pyrrhotite, ; galena, 7.5-7.8; barite, ; magnetite, ; lig nite, I•1-1.2. In oil exploration, the following densities are sig nificant : Salt, 2•r-2.2; igneous rocks, 2.5-3.o; sedimentary rocks, 1.6 to 2.8. The latter increases with consolidation and geologic age and is the reason why faults and anticlines, in which older formations have been placed in the same elevation as younger formations, may be detected by gravity methods.

Three methods of gravity prospecting may be distinguished : (I) The (Eoetvoes) torsion balance, (2) the pendulum, and (3) the gravimeter. In the first method (see fig. 1), the horizontal variations of the horizontal and vertical gravity components are measured; in the second and third, relative gravity is observed. The torsion balance as used in geophysical exploration consists of two independently suspended beams reversed 18o° with respect to one another and capable of rotation about a vertical axis rep resented by a fine platinum-iridium or tungsten wire. The beam is loaded with two weights; one is attached directly to one end while the other is suspended by a wire from the other end. In re cent models this suspension is replaced by a beam tilted 45 de grees. The quantities measured by the torsion balance may be expressed as derivatives of the gravity potential ; its action may be explained by considering the geometric disposition of the sur faces of equal potential which are at any point perpendicular to the direction of gravity. If an equipotential surface placed through the beam deviates from the spherical shape, differ ences in the horizontal gravity components acting on the beam weights are produced ; the beam deflection is proportional to two quantities related to the curvature of the equipotential sur face, known as "curvature values." Furthermore, if two converg ing equipotential surfaces, above one another, are placed through the upper and lower weight, the resulting difference in the direc tion of gravity forces acting on the upper and lower weights will deflect the beam. The convergence of the equipotential surfaces is proportional to the horizontal variation of gravity which may be resolved into two components commonly referred to as north and east "gradient" of gravity. To determine all four quantities the beam deflections must be observed in different positions of the entire instrument ; for a double beam instrument, three po sitions are required. Usually the instrument is rotated auto matically into these positions, left in each of them until the beams have come to rest and a record taken photographically of the beam position with reference to the case. From the rec ords, gradients and curvature values are calculated ; the former are represented as arrows whose length and direction indicate the amount and direction of horizontal gravity variation. Curvature values are represented by straight lines, their direction and length indicating the direction of minimum curvature and deviation from the spherical shape of the equipotential surfaces of gravity.

The pendulum (see fig. 5) measures changes in gravity by vari ations in its period of oscillation which is determined with an accuracy of one ten-millionth of a second. One pendulum is set up on a base station ; its oscillations are transmitted by radio, through photoelectric pickup, to the field stations where they are recorded photographically together with the oscillations of the field pendulum. Generally two or three pendulums are swung simultaneously on the same support to eliminate the effect of its flexure. Results are obtained in form of gravity differences against a base station.

Gravity variations may also be measured statically by observ ing variations in gravity pull on the weight of a balance beam in comparison with the restituting force of a spring (see fig. 3) . Such an instrument is called a "gravimeter." Interpretation of gravity anomalies obtained by pendulum or gravimeter is both qualitative and quantitative. A gravity high may indicate a change to a heavier formation in the same level or the rise of a given formation and vice versa. For quantitative interpretation, effects of geologic bodies of assumed densities, di mensions and depths are calculated and varied until reasonable agreement with the field findings is obtained. These calculations are based on the Newtonian potential of such bodies and its derivatives when they are limited in all directions and on their logarithmic potential and its derivatives if they are extended in the strike. Calculations are facilitated by diagrams consisting of sections of mass elements so calculated in respect to dimen sions and distance that their effect at the station is identical. Interpretation procedure in torsion balance work is similar in principle; while for calculations of gravity anomalies only the first derivative of the potential with respect to the vertical is required, derivatives of higher order are calculated for torsion balance interpretation. For bodies extended in the strike, the required quantities are the second derivatives of the (logarithmic) potential with respect to the horizontal for curvature values and with respect to both horizontal and vertical for the gradients.

Gravity values obtained with pendulum or gravimeter must be corrected for terrain, normal gravity, elevation, and regional gravity variation. Torsion balance data require a more elaborate terrain correction and an allowance for variations due to the shape of the earth and to regional geologic structure.

(c) Magnetic Methods.

Most magnetic anomalies are due to the presence of magnetite in igneous and sedimentary rocks and in iron ore deposits. Magnetite has the greatest "magnetic susceptibility" (see MAGNETISM). In IOC units, susceptibilities of magnetite range from i to I next is pyrrhotite with I to other iron minerals are but weakly magnetic, hematite being of the order of Igneous rocks have susceptibilities ranging from I to and sedimentary rocks from I o to I o2.

There exists a great variety of instruments for magnetic pros pecting, from the simple mining compass used in the I7th century to the sensitive magnetic field balances permitting of intensity measurements with an accuracy greater than I/Io,000 part of the earth's field. It is possible to measure any angular or intensity component, but experience has shown that vertical intensity anomalies are the most interpretable; in some instances, supple mentary horizontal intensity measurements are useful. The in strument most widely used is the Schmidt Vertical Magnetometer (see fig. 4). It consists of a magnetic system suspended by a knife edge and oriented at right angles to the magnetic Meri dian. Thus, magnetic vertical intensity is compared with gravity (assumed to be constant) ; the deflections of the system are read on an autocollimation telescope. Schmidt has also designed a bal ance for horizontal intensity measurements consisting of a mag netic system suspended to oscillate in the magnetic meridian. In strument readings are referred to a base, corrected for tempera ture and diurnal variation (see TERRESTRIAL MAGNETISM), mul tiplied by the scale value and corrected for the normal geographic variation of the earth's magnetic field. Magnetic anomalies are expressed in "Gammas" (I Gauss units) and magnetic con tour maps prepared.

Interpretation of magnetic anomalies in terms of geologic struc ture is largely qualitative and empirical ; the magnetic method is primarily a reconnaissance method to be followed, at least in oil exploration, with other more quantitative geophysical methods. In certain cases (mining problems) it is possible to make quanti tative depth interpretations. These are largely of an indirect na ture; magnetic anomalies of poles and magnets can be calculated from their potential; if the bodies are extended in the strike, the logarithmic potential takes the place of the Newtonian potential. In the former, the magnetic anomaly is inversely proportional to the square of distance; in the latter, inversely to the first power of distance. To bodies magnetized homogeneously by induction in the earth's field, a theorem formulated by Poisson applies; their magnetic potential is equal to their intensity of magnetiza tion, multiplied by the gravity component in the direction of magnetization. As magnetic intensities are gradients of magnetic potential, it follows that they are related to the gravity gradients measured with the Eoetvoes torsion balance (see above). Hence, magnetic effects of given bodies can be calculated by the same analytical and graphical methods as used in torsion balance work.