Battle of Gaugamela Arbela

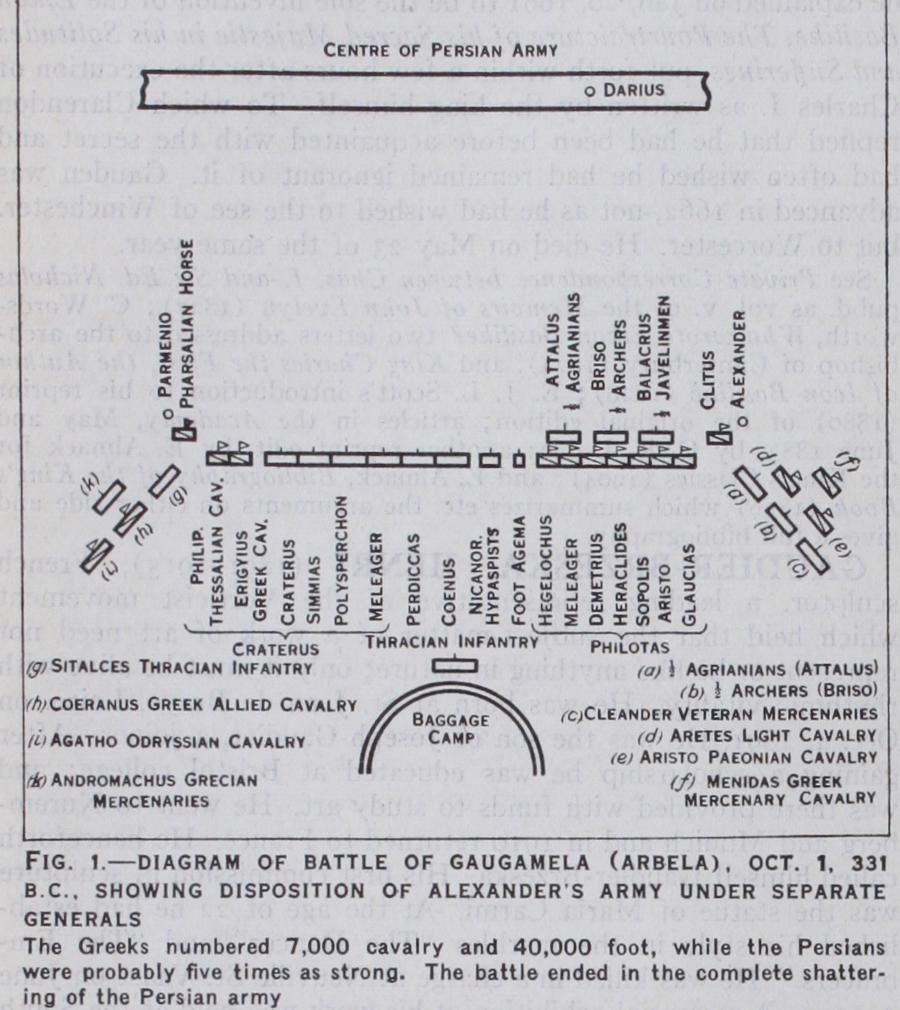

GAUGAMELA (ARBELA), BATTLE OF (Oct. i, B.c.). After his defeat at Issus, Darius assembled a vast horde of men at Babylon. Thence, marching northwards, he crossed to the left bank of the Tigris, and established his magazines and harems at Arbela (Erbil). From Arbela he moved forward to Gaugamela, some 32 miles westwards. Having conquered Egypt, Alexander marched northwards through Palestine, crossed the Tigris at Bezabdi, north of modern Mosul, and, learning of the Persian king's whereabouts, he at once moved forward with a picked force of cavalry. Having located the enemy, he rested his army for four days and fortified his camp. Whilst this was taking place, Darius deployed his army on the plains of Gauga mela, which he converted into a huge parade ground by levelling it. On the fourth night Alexander advanced, but when 3 z miles distant from him he called a halt, and assembled his generals. Parmenio suggested that they should encamp where they were, and reconnoitre the ground and the enemy. To this Alexander agreed, and whilst the camp was being fortified, "he took the light infantry and the companion cavalry and went all round, recon noitring the whole country where he was about to fight the battle." On his return he called together a conference at which he dis cussed what he had seen, and urged upon his generals the im portance of the immediate execution of orders. Whilst the soldiers were resting, Parmenio came to Alexander's tent and suggested a night attack. This proposal Alexander refused to consider, his reason (more probable than the story of his disdaining such craft) being that in the approaching battle he had planned to deliver a decisive blow, and he knew well the difficulties coin cident with night operations. Having rejected this advice, Alexander drew up his army. The phalanx was marshalled in the centre, the right wing consisting of its three right divi sions, the hypaspists, the agema and the Companion cavalry; the left wing of the remaining three divisions of the phalanx, the Grecian cavalry and the Thessalian cavalry. Thus far the order of battle was normal. The problem which faced Alexander was very similar to that which confronted Cyrus in Xenophon's ac count of the battle of Thymbra. Alexander applied the tactics made use of at Thymbra. Behind his front he drew up a reserve force consisting of two flying columns ; these he posted one be hind each wing at an angle to the front, so that they might take the enemy in flank should an attempt be made to turn the wings; or, if this did not take place, then they were to wheel in wards and reinforce the main army. In front of the Companion cavalry he posted half the Agrianians, archers and javelin-men to oppose the charge of the Persian chariots. The baggage guard consisted of Thracian infantry. In all Alexander's army numbered 7,000 cavalry and 40,000 foot, the Persians were, in all probabil ity, about five times as strong. This order of battle should be kept clearly in mind, for, as it will be seen, it was through Alexander's ability to develop his tactics from it that he won the battle.

The Battle.

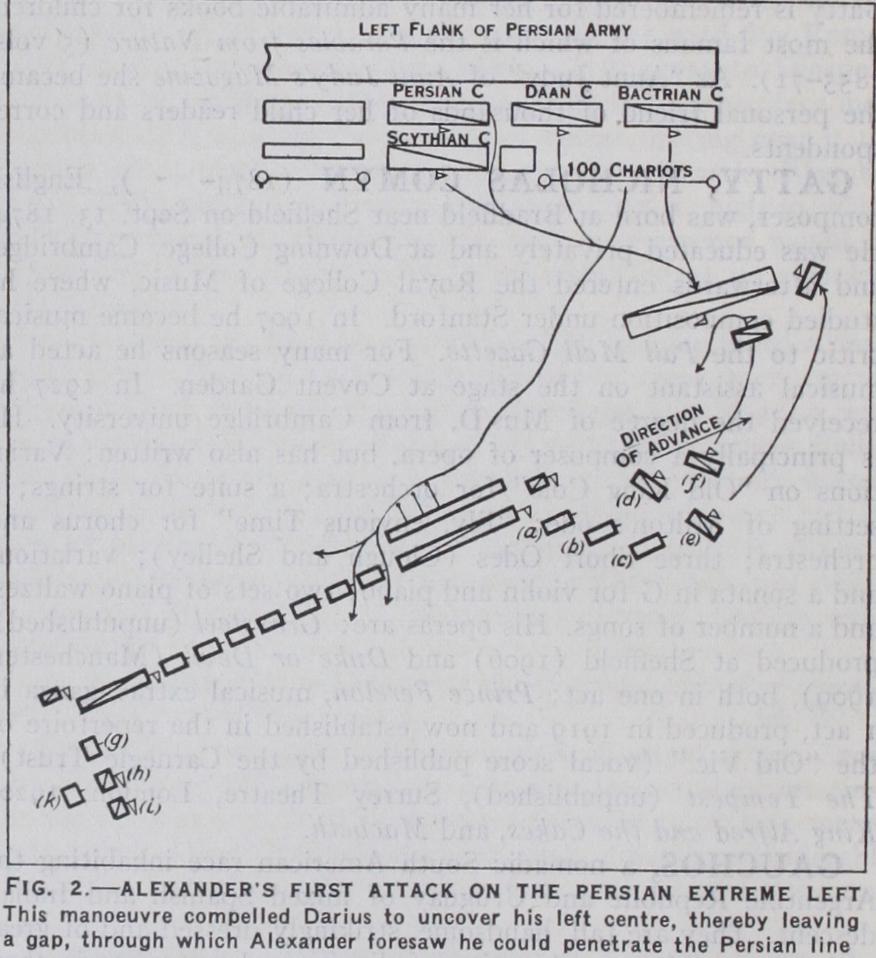

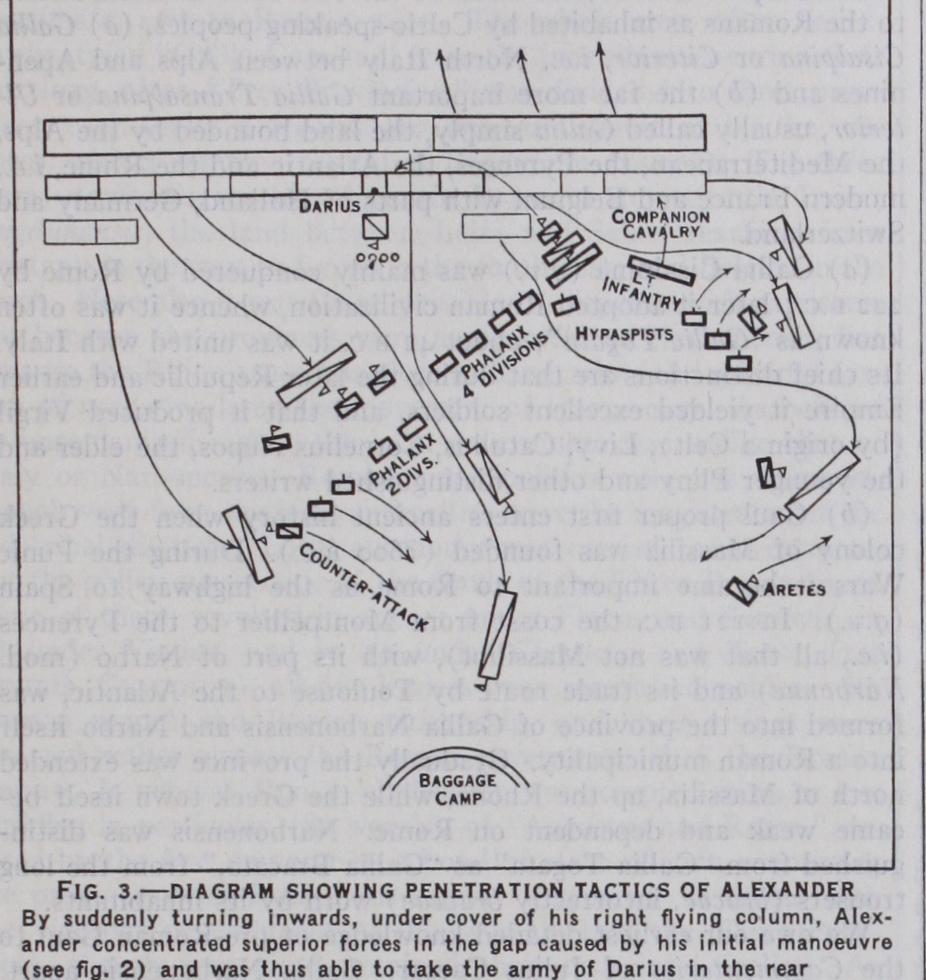

The initiative was taken by Alexander. He ad vanced, not directly on the Persians, but towards their left, and so compelled Darius to move on to the unlevelled ground. Darius, fearing that his chariots would become useless, ordered his left wing cavalry to ride round Alexander's right and halt him. Alex ander met this attack with his light cavalry, and a general cavalry engagement took place. Then Darius launched his chariots, but they never got home, as the charioteers were shot down by the light infantry in front of the Companion cavalry. The Persian left was now unmasked and in some confusion, whereupon Alexander wheeled round the Companion cavalry and with the four right di visions of the phalanx he led them towards the gap formed in the Persian front by the advance of their cavalry, and made straight for Darius. This cavalry charge, closely supported on its left by the dense array of bristling pikes in echelon, smote such terror into Darius that he fled the field. Meanwhile the Persian cavalry on Alexander's original right, finding their rear threatened took to flight, and the Macedonians, following up the fugitives, slaughtered them. The left wing, on account of the diagonal march, was in rear of the right, and the impetuous advance of Alexander appears to have created a gap between it and the right wing. Through this gap the Indian and Persian cavalry burst, and advanced towards the baggage camp. While this action was in progress, the Persian cavalry on Darius's right wing rode round Alexander's left wing and attacked Parmenio in flank. Parmenio, now completely sur rounded, sent a messenger to Alexander informing him of his critical situation. He received this message whilst he was pursu ing the fragments of the Persian left wing, and at once wheeled round with the Companion cavalry, and led them against the Persian right. The Persian cavalry, who were now falling back, finding their retreat menaced, fought stubbornly. "They struck and were struck without quarter" but were routed by Alexander. The pursuit was now taken up, and was continued until midnight, when a forced march was made on Arbela. About 32 miles were covered, but in vain, for Darius made good his escape. Arrian states that the Persians lost 300,00o in killed and Alexander only zoo, and i,000 horses. These figures are obviously unreliable.

Tactics.

This battle was not won by reckless courage but by audacity tempered by a wonderful grasp of what the enemy in tended to do, and how his actions could be turned to advantage. This is clearly seen if the diagrams are studied. The order of battle is the normal one, but out of it is developed a very different type of attack to those of the battles of Granicus and Issus. Alex ander is never obsessed by past successes, also he never invents what may be called experimental attacks. What he does is to measure up his antagonist and to act accordingly : First he seeks information; this is the foundation of his security, for in spite of his audacity security is always the foundation of his offensive action. Once he has made up his mind he distributes his force economically; his order of battle consists of a protective left and an offensive right, and in his right he concentrates his punch. Having secured his plan, he rapidly moves towards the Persian left flank, not only to get beyond the level ground, but to prevent a double envelopment, and to increase the distance between his left and the Persian right. This will enable him to shatter the Persian left before the Persian right can annihilate his own left. Also, if he can only draw the Persian right well inwards, should he be able to smash the enemy's left, he will then be in a position to take their right in reverse. In diagram 2, the position of Darius, the de cisive point, is off the plan to the left, yet it is the point Alexander intends to strike. He opens the battle by moving away from it, and so compels Darius to uncover the immediate left flank of his centre. Though now well placed to attack in oblique order the outer flank of the Persian left wing he does not do so, for the decisive point is not the left wing but the centre. In diagram 3 it will be seen that under cover of his right flying column, he sud denly obliques inwards, and concentrates superiority of force op posite the gap once filled by the Scythian and Persian cavalry. Through this gap he charges at top speed and strikes Darius in rear. This charge succeeds, not because the Companion cavalry are advancing at top speed, but because their mobility is developed from the security afforded by the flying column and the phalanx.

The penetration by shock is absolutely successful. Gaugamela is one of the most perfect examples of the tactics of penetration to be found in history.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.--Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander, Diodorus Siculus; Bibliography.--Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander, Diodorus Siculus; Q. Curtius; Rustow and Kochly Geschichte der griechischen Kriegs wesens (1852) ; G. Grote, History of Greece (1906) ; H. Delbruck, Geschichte der Kriegskunst (1908) ; J. G. Droysen, Geschichte Alex anders des Grossen (1917) ; The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. vi. . (J. F. C. F.) GAUGUIN, PAUL (1848-1903), French painter, one of the pioneers of the Post-Impressionist movement. He was born in Paris on June 7, 1848, the son of a journalist from Orleans and of a mother partly of Peruvian descent. He spent his child hood in Peru and at Orleans, and after having done his military service in the marines he entered the banking firm of Bertin in Paris in 1871. In 1873 he married Mette-Sophie Gad, a Danish lady. In 1875 he began to spend his free time in painting. En couraged by his friend, C. Pissaro, he acquired the Impressionist technique. His interest in art took more and more hold of him, and in 1881 he decided to give up his appointment at the bank. His means soon gave out and after an unfortunate attempt to get assistance from his wife's relations at Copenhagen, he separated from her and his children, returning to Paris without means. A period of travel followed. He worked on the island of Martinique (1887-88) and then went to Pont Aven in the Bretagne, where he soon became the leading spirit of a group of painters.

The movement thus started was known as "Synthesism." Gauguin himself was not a theorist. He wished to be rid of all that might intervene between the artist's vision and his canvas; but the other members of the group felt otherwise. Emile Bernard lectured on the synthetic doctrine, Filiger contributed his medi aeval fancies, Serusier propagated the new ideas ; he clarified the vague doctrines of Gauguin. The new tendency is explained by Maurice Denis, one of Serusier's disciples in Paris ; he says : "It was on our reassembling in 1888 that the name of Gauguin was revealed to us by Serusier, who had just returned from Pont Aven and who allowed us to see not without a show of mystery the lid of a cigar box, on which we could make out a shapeless landscape synthetically designed in violet, vermillion, Veronese green and other unmixed colours, just as they are pressed out of a tube, almost without white in them. `How does that tree appear to you,' Gauguin had asked—`very green?—Well then use green —the finest green on your palette—and that shadow is rather blue? Do not be afraid to paint it as blue as possible.' " "Thus," continues Denis, "was presented to us for the first time the fruit ful conception of the plane surface covered with colours put together in a certain order . . . we learned that every work of art is a transposition, a caricature, the passionate equivalent of a sensation which has been experienced. . . . Gauguin freed us from all restraints which the idea of copying placed on our painter's instinct. . . . Henceforth we aspired to express our own personality. . . . If it was permissible to use vermillion in paint ing a tree which seemed to us at that moment reddish . . . why not stress even to the point of deformation the curve of a beauti ful shoulder, exaggerate the pearly whiteness of a carnation, stiffen the symmetry of boughs unmoved by a breath of air?" (Theories 189o-191o, published in 1920.) Thus Gauguin's ideas were taken up by a group of young students in Paris, which included Bonnard Denis, Ibels, Ranson, Vuillard and Maillol. In 1889 "the school of Pont Aven" moved to Pouldu near by. Their life there and the inn at Pouldu, the rendezvous of artists, which was adorned by Gauguin, was de scribed by Mr. Ch. Chasse in l'Occident (1903) . In 1888 Gau guin went to Arles to meet his friend, Van Gogh. The two artists had planned to work together, but Van Gogh succumbed to an attack of lunacy and Gauguin left him. (See P. Gauguin, Avant et Apres.) Among Gauguin's best work of this period are "Le Christe Jaune," and "La Lutte de l'Ange avec Jacob." He copied Manet's "Olympia," which he considered one of the masterpieces of the age, he etched a portrait of Mallarme, executed some litho graphs and carved reliefs in wood. But in spite of all his efforts his financial position did not improve. His journey to Martinique had inspired him with a love for the tropics and he conceived a plan of going to the South Seas where he could live cheaply and devote himself to his vocation. He sold all his pictures by auction for 9,86o frcs. and went to the island of Tahiti in 1891. There he lived a simple life with the natives which he described in his autobiographical novel Noa Noa.

On his return to Paris he exhibited his paintings at Durand Ruel, but the life in the big city no longer suited him ; he left for Tahiti in 1895 never to return. Out there, inspired by his admira tion for primitive life, for the luminous colour of the tropical landscape, he produced paintings of great decorative beauty and originality. "L'esprit Veille," "Seule," "Devant la Case," "La Fuite" and "Jours Delicieux" are among his most notable works. They represent the bronzed native Maoris in their surroundings of exotic plants and primitive dwellings. In 1901 he moved to Dominiha on the Marquesas isles. He built himself a house and decorated it with carvings and paintings. The natives treated him as one of their own and he sided with them against the over bearing European representatives of the administration. The end of his life was approaching; he lived in extreme want; in order to pay his taxes he worked in a Government office for 6 frcs. a day; his health was failing. He died on May 9, 1903, and was buried in the Mission cemetery. Victor Segalen, a navy doctor and writer, who was in the Marquesas isles at the time, gave a vivid and sad account of his end (Mercure de France, June 1904).

His last important picture, entitled "D'ou venons nous? Que sommes-nous? ou allons-nous?" is one of his masterpieces. It was painted under the shadow of an attempted suicide. His de scription of this work in a letter to his friend, D. de Montfreid, is of interest, as it throws light on his artistic creed. "Bef ore I died I wished to paint a large canvas that I had in mind, and I worked day and night that whole month in an incredible fever. To be sure it is not done like a Puvis de Chavannes, sketch after nature, preparatory cartoon, etc. It is all done straight from the brush on the sackcloth full of knots and wrinkles, so the appear ance is terribly rough. . . . I put in it all my energy, a passion so dolorous, amid circumstances so terrible, and so clear was my vision that the haste of the execution is lost and life surges up. It does not stink of models, of technique, or of pretended rules, of which I have always fought shy, though sometimes with fear. It is a canvas f our metres, fifty long and one metre, seventy high. The two upper corners are chrome yellow, with an inscrip tion on the left and my name on the right, like a fresco whose corners are spoiled with age and which is appliqueed upon a golden wall. To the right at the lower end a sleeping child and three crouching women. Two figures dressed in purple confide their thoughts to one another. An enormous crouching figure, out of all proportion and intentionally so, raises its arms and stares in astonishment upon these two, who dare to think of their destiny ; a figure in the centre is picking fruit ; two cats near a child; a white goat; an idol, its arms mysteriously raised in a sort of rhythm seems to indicate the Beyond. Then, lastly, an old woman nearing death appears to accept everything. . . . She completed the story. . . . It is all on the bank of a river in the woods. In the background the ocean, then the mountains of a neighbouring island. Despite changes of tone the colouring of the landscape is constant—either blue or Veronese green. Where does the execution of a painting commence and where does it end? At that moment when the most intense emotions are in fusion in the depths of one's being, when they burst forth like lava from a volcano . . . ? The work is created suddenly, brutally if you like, and is not its appearance great, almost superhuman?" Gauguin, then, had left Impressionism behind ; he had profited by its technique in the use of using colours pure and unmixed; but his work was impregnated with symbolism, his design was ex pressive, his colour arrangements decorative. His influence on modern art was far-reaching. Besides the school of Pont Aven and the Synthesists, he inspired such artists as Ed. Munch and Toulouse Lautrec. His ideas revolutionized poster design and design in all Arts and Crafts work (Van de Velde, Lemmen, Galle-Nancy.) His primitive woodcarving and his terra-cotta figure called "Oviri," the Tahitan Diana, was admired by such artists as Picasso and led to the appreciation of negro sculpture. His lithographs and woodcuts opened new fields in the graphic arts.

See Jean de Rotonchamp, Paul Gauguin (5925) ; Ch. Morice, Paul Gauguin (1919) ; Gauguin's writings: Noa Noa (1924), the manu script with original illustrations is in the possession of Mr. D. de Montfreid, who also owns the manuscripts of Choses Diverses (1896 97) ; and of Le Sourire, a satirical journal written in Tahiti; Racontars d'un Rapin (1902), written on the Marquesas islands, is reproduced for the most part in Rotonchamp's book: Avant et Apres, published by Charles Morice in Vers et Prose (1903) ; the manuscript was repro duced in facsimile (Leipzig, 1919) ; Lettres de Paul Gauguin a G. D. de Montfreid (592o) ; The Intimate Journal of P. Gauguin, with a preface by Emile Gauguin (1923) ; M. Guerin, L'oeuvre Grave de Gauguin (1927). (I. A. R.)