English Glass

ENGLISH GLASS The British people have contributed much to the well-being of the world by their manufacture of glass. Crystal glass, plate glass, window glass and bottles are all produced in large quantity by British factories, but of these, crystal or flint-glass, is best known. Flint-glass is really a glass of lead, a heavy brilliant crys tal-like glass, composed of lead potash and sand ; as powdered flints happened to be used at first, instead of sand, the name flint glass remained. It is essentially a useful glass, and from its very nature is incapable of the artistic development seen in the fragile and easily worked glass of Venice. The British glass-makers did however make the most of a beautiful but intractable material and their work is marked at most periods by seemliness and good taste; simple useful shapes were chosen for glass vessels of all kinds, and decorated in ways most appropriate to the nature of flint-glass, with cutting as the most obvious means; many other experiments in decoration were tried, but all were abandoned in favour of cutting and engraving, which have been practised in England for over 200 years and still retain their popularity.

The 16th and 17th Centuries.

Flint-glass was introduced about 1675. Before that time glass for table service had been made in England on a small scale, but it was really Venetian, in weight and of fragile material, and in form mere copies of simple Venice examples, made by Italian glass-makers, or their English pupils. Few of them have come down to us intact, but fragments, excavated in London and elsewhere, have revealed their actual shape and quality. Edward VI. induced a few wandering Venetian glass-makers to settle for a while in London, and again in 1 S 7o Italian glass-makers appeared. Elizabeth procured the services of a Venetian, Jacob Verzellini, and in 1575 granted him a patent or monopoly for making Venetian specimens (Plate XIV., fig. 3). In 1592 the glass monopoly was transferred to Sir Jerome Bowes, and in 1615 to Sir Robert Mansell, who had good results with the help of Italian glass-workers (figs. 1 and 2, p. 408). The Protectorate put an end to glassmaking by monopoly, and for some time John Greene and other London glass-sellers imported their wares from Venice, which were generally made according to Eng lish designs (fig. 3) . One good result came from these early experi ments in glass-making. In 1615, owing to the demands of the navy, the glass-makers were forbidden to burn wood as fuel, and in consequence they had to use coal furnaces and closed glass pots giving intense heat, an essential to flint-glass making. Again, about 166o, Italian glass-makers were brought over to London, and with the help of one of them (Seignior De Costa) George Ravenscroft evolved the famous flint-glass about the year 1675, marking his glass with a glass seal, bearing the device of a raven's head (fig. 4) ; his rivals followed suit, so that five different glass trademarks of this period are now known. This custom of marking glass was dropped about 169o, when flint-glass had become generally known. Ornate drinking-glasses made about this time (fig. 5), were due to the prevailing taste for highly ornamented table service, for which the silversmiths were mainly responsible, but just before 1700 this fashion changed, and there followed a period of simple tableware, lasting nearly 25 years.

The 18th Century.--In

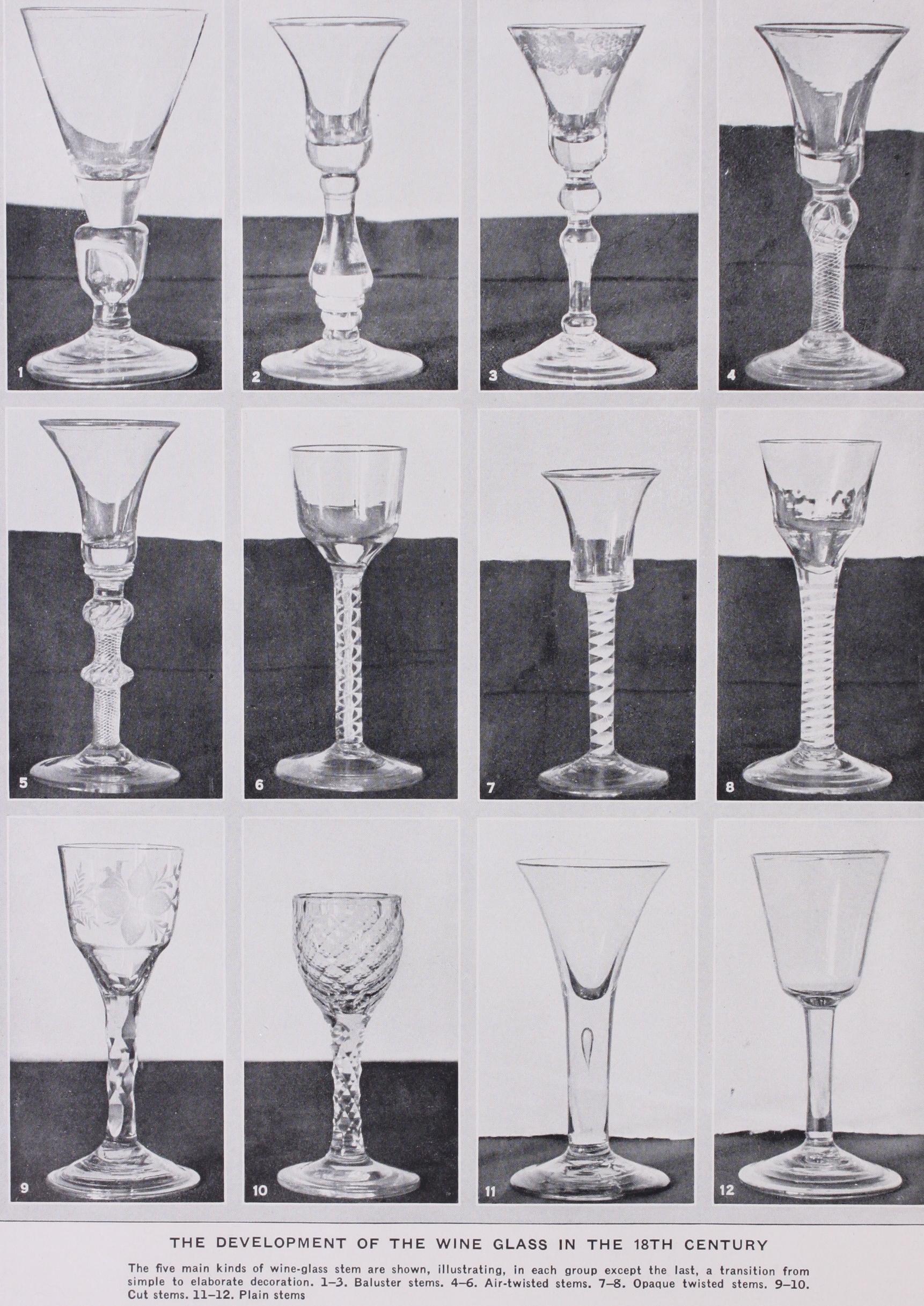

the 18th century the decoration of drinking-glasses was mainly stem decoration, and there were five different kinds of stem in fashion during this period without count ing minor variations (Plate XIII.). These are known to collectors today as the baluster stem, the plain stem, the air-twisted stem, the opaque-twisted stem, and the cut stem. From 1747 to 176o all kinds were being made simultaneously; but out of this welter of competing fashions, only two styles survived : the cut stem for fashionable glasses and the plain stem for those of ordinary use. The taste for elaborate stem decoration arose first of all from the national craving for intricate artistic ornament of all kinds, which started about 172o. Stem decoration of glasses was encour aged in 1746 when the Government laid a tax upon glass accord ing to its weight rather than its value, so that it became most profitable to make and sell elaborately decorated glass.Venetian glasses of the r 7th century, whether made abroad or in England, had generally hollow stems blown into various shapely mouldings, known as baluster stems ; this name is still given to all stems with one or more distinct mouldings, or swellings. The difficulty of making an entirely hollow stem in flint-glass soon led British glass-workers to make a solid baluster stem, or one with only a small hollow core, like a large teardrop (Plate XIII., fig. r). These drinking glasses were heavy and had at first large bowls and short stems. Gradually the stem was lengthened out and more elaborately modelled, and the bowl was reduced in size (Plate XIII., fig. 2).

After the Glass Excise Act (1745) heavy glass was no longer profitable to make, but more slender versions of the baluster stem survived till 1768, having simple "olive buttons" in the stem, and often engraved (Plate XIII., fig. 3) .

Tall goblets with plain stems were made in the r 7th century as suitable for special beverages. Until 1746 they were generally of substantial size, of good quality and still used for special kinds of wine (Plate XIII., fig. r r), but the excise duty made these simple types unpopular, and thenceforward wine glasses with plain stems were generally made smaller and lighter, to be used in the tavern and household (Plate XIII., fig. 12).

Drinking-glasses with the air-twisted stem were in fashion in England from about 1735 to 176o, and in Ireland till somewhat later. An air-twist in the stem was made originally by inserting a number of large air bubbles in the thickened base of a partly formed bowl and then drawing down the bowl into a stem and at the same time twisting the stem; the air bubbles were thus contracted and formed into corkscrew air-lines within the stem. At first the result was a coarse, irregular spiral (Plate XIII., fig.

4), but with practice the regularity and symmetry of the air spiral were improved. Air-twisted stems were sometimes made sepa rately, and were then welded to the bowl as well as to the foot of the glass (Plate XIII., fig. 5) ; such stems are remarkable for their extraordinary intricacy (Plate XIII., fig. 6). An almost national type of decoration, the air-twisted stem could only be made well with the best flint-glass. The glasses cost at the time 7d. each.

Drinking-glasses with the opaque-twisted stem originated in Bohemia; they came into fashion in England about 1746 as a means of evading the glass tax, which omitted the taxation of the enamelled kind. The stem was here formed of opaque enamel glass threads, encased within clear glass. This result was obtained with the aid of a cylindrical mould first lined with clear glass, and the centre then filled with one or more canes of enamel glass ; it was then heated in order to weld the contents together. Next the large lump of striped glass was withdrawn from the mould, re twisted and drawn out like a long rod, to be cut up later into short lengths, which formed the stems of a set of glasses. At first, while the process was in an experimental stage, the glasses had a single broad band of enamel glass, like a twisted tape, within the stem (Plate XIII., fig. 7). Later kinds have spirals of many fine enamel threads most ingeniously arranged (Plate XIII., fig. 8). As many as 56 fine threads have been counted in a single stem. White and coloured enamel glass was used to form the opaque spiral. In 1777 the Second Glass Excise Act taxed enamel glass, and the glasses soon went out of use.

Glasses with cut stems had the surface of the stem cut into small grooves, or facets, which formed a regular and continuous diamond pattern round the stem. The glass was cut by being held firmly against a revolving iron wheel called the "scalloper's mill"; the cut facets were then smoothed with a stone wheel and finally polished with a wood and brush wheel. The decoration of glass by cutting and engraving came from Bohemia and was introduced into London shortly before 172o. After 1745 cut wineglasses grew in popularity, until by 1777 they were almost the only fashionable kind produced. Furthermore, they were made shorter and the style of cutting began to change. Stems were often cut with long upright grooves like the flutings on a pillar (fig. 6). Just before r 800 further changes were made, both in shape and style of cut ting, the bowls being more heavily cut than the stems (fig. 7). Since then there has been little change in the style of cutting, although after 1845, when the glass excise was abolished, taller goblets were again made.

Cut glass has never been cheap; in r755 simple types cost 7d each (Plate XIII., fig. 9) and more elaborate pieces as much as 2S. (Plate XIII., fig. ro).

Glass vessels were also decorated by having various designs scratched or cut upon the bowl. The earliest method was simply to scratch the design on the bowl with a diamond point (Plate XIV., fig. r), but after 172o engraving was generally done in the Bohemian manner, by cutting the glass with small copper and stone wheels (Plate XIII., figs. 3 and 9), which is a more difficult and delicate method of cutting glass. Etching on the glass with acids was not much practised in England until more recent times. The most interesting engraved glasses, from a sentimental point of view, are those relating to the fallen house of Stuart, and no other country in the world possesses such a series of interesting political glasses (Plate XIV., fig. 5).

Cut Glass.

The introduction of glass-cutting was commer cially an event of supreme importance to the welfare of glass making in Great Britain and Ireland. At first Bohemian glass cutters were employed by a few of the more enterprising London glass sellers ; John Akerman, employing a man named Haedy, advertised "diamond-cut flint glasses" in 1719. Haedy eventually acquired a business of his own, which prospered for three genera tions. Benjamin Payne, another London glass seller, advertised "diamond-cut flint glass" many times from 1735 onwards; he too must have employed a Bohemian glass-cutter. Thomas Betts, a London glass-cutter (1738-67) at first employed a Bohemian, Andrew Pawl, but afterwards instructed pupils himself. Jerom Johnson a self-taught London glass-cutter, became successful and is found selling cut-glass for exportation in These men laid the foundation of the cut-glass trade in London, where it was "greatly in vogue" in 1747. Bohemian glass-cutters continued to come over and assist in the production of fine cut glass, e.g., Tresler, Laurikus, Ayckbowm, Gerner and Benedict, whose work in London between i 7 5o and 1 Boo is now well known. After i 75o the art of glass-cutting spread gradually to other parts of the country. And by the middle of the 18th century London cut-glass had displaced the Bohemian cut glass in European markets.Originally, the most popular articles in cut-glass were lustres (Plate XIV., fig. 2) and sets of dessert glasses (Plate XIV., fig. I) ; but by 1 742 all manner of cut-glass articles were being adver tised. At first cutting was confined to hollow diamond patterns until 177o, when the fluted patterns came into fashion ; finally, convex or raised diamond patterns and prismatic cutting were in troduced (c. 1800). These last were quite British in type, and are the styles of cutting most in favour today. Specimens of Irish cut glass, which began to be made on a large scale in 178o, sufficiently illustrate this stage of the national glass-cutting (Plate XIV., fig. 6) ; in design no very great advance was made after 1825. From 1835 onwards there was a return to the simple fluted style of cutting for wine-glasses, but they were then of a shape unsuitable for this decoration.

The present cut-glass designs are more or less copied from those of the period 1800-3o, popularly called Waterford. The use of steam engines to drive the cutting machines led the glass-cutters to sacrifice the natural blown forms of glass for the sake of a masterly display of deep and accurate cutting, and glasses became too deeply and profusely cut, emitting a blaze of prismatic light, but having an unpleasantly rough surface. The worst types pro duced were early Victorian ; John Ruskin, impressed with the vulgarity of these glasses, wrote a sweeping condemnation of all cut-glass, which for a time brought the craft into discredit and undoubtedly injured the national glass trade. Decoration by cut ting almost disappeared for a time. Latterly, however, cut-glass has recovered much of its former popularity. The distinguishing features of modern flint-glass are its purity and,its cold perfection. Glass-making is now treated scientifically for, with world wide competition to face, economy and efficiency are essential to the prosperity of the trade, which owes not a little to the founda tion of a Society of Glass Technology at Sheffield university, and to the researches and experiments carried on there under the supervision of Prof. W. E. S. Turner.